Published online Oct 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i10.534

Revised: June 20, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Published online: October 16, 2014

Processing time: 176 Days and 19.7 Hours

AIM: To study the comparison in terms of root coverage the effect of gingival massaging using an ayurvedic product and semilunar coronally repositioned flap (SCRF) to assess the treatment outcomes in the management of Miller’s class I gingival recessions over a-6 mo period.

METHODS: The present study comprised of total of 90 sites of Miller’s class-I gingival recessions in the maxillary anteriors, the sites were divided into three groups each comprising 30 sites, Group I-were treated by massaging using a Placebo (Ghee) Group II-were treated by massaging using an ayurvedic product (irimedadi taila). Group III-were treated by SCRF. Clinical parameters assessed included recession height, recession width, probing pocket depth, width of attached gingiva, clinical attachment level and thickness of keratinized tissue. Clinical recordings were performed at baseline and 6 mo later. The results were analyzed to determine improvements in the clinical parameters. The comparison was done using Wilcoxon signed rank test. The overall differences in the clinical improvements between the three groups was done using Kruskal-Wallis test. The probability value (P-value) of less than 0.01 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS: Non-surgical periodontal therapy and gingival massaging improves facial gingival recessions and prevents further progression of mucogingival defects. Root coverage was achieved in both the experimental groups. The SCRF group proved to be superior in terms of all the clinical parameters.

CONCLUSION: Root coverage is significantly better with semilunar coronally repositioned flap compared with the gingival massaging technique in the treatment of shallow maxillary Miller class I gingival recession defects.

Core tip: Gingival recession is the migration of the gingival margin apical to the cemento-enamel junction. A variety of surgical procedures have been described for the correction and management of mucogngival deformities and defects, with a variable degree of success. However, it should be emphasized that shallow recessions are subject to progression, but there are no case reports or controlled clinical trials to compare the effects of gingival massaging in the treatment of gingival recessions. The aim of our study was to compare in terms of root coverage the effect of gingival massaging using an ayurvedic product and semilunar coronally repositioned flap to assess the treatment outcomes in the management of Miller’s class I gingival recessions over a 6 mo period.

- Citation: Mishra AK, Kumathalli K, Sridhar R, Maru R, Mangal B, Kedia S, Shrihatti R. Comparison of semilunar coronally repositioned flap with gingival massaging using an Ayurvedic product (irimedadi taila) in the treatment of class-I gingival recession: A clinical study. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(10): 534-540

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i10/534.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i10.534

Gingival recession is defined as the migration of the marginal tissue apical to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ). Its occurrence is common and its prevalence increases with age. The recession of the gingiva resultant of attachment loss and root exposure may be associated with one or more tooth surfaces and lead to clinical problems such as dentinal hypersensitivity, root caries, cervical root abrasions and diminished cosmetic appeal[1,2].

Miller[3] (1985) in his classification of recession has described class I recession as marginal tissue recession that does not extend up to the mucogingival junction and not accompanied by any loss of bone or soft tissue in the interdental area. Very often, it is the most coronal millimeter of recession which is visible when the patient smiles. Thus even a marginal gingival recession, can account for major aesthetic problems and persistent dentinal hypersensitivity[4]. In order to combat these clinical problems, various treatment modalities have been proposed that have in due course evolved based on the knowledge of healing of the gingiva and the attachment system.

Aimetti et al[5] (2005) proposed non-surgical therapy viz periodic scaling and polishing for the treatment of shallow gingival recession. It was hypothesized that reduction of root convexity and elimination of microbial toxins from the root surface by scaling and root planing promotes creeping attachment of gingival margin. Tarnow[6] (1986) introduced the semilunar coronally repositioned flap (SCRF) procedure as one of the surgical approaches to treat Class I gingival recessions. It entails coronal advancement of a semilunar flap without any tension or disturbance to the subjacent tissues. The flap is stabilized in the desirable position under gravity, hence a sutureless technique.

Gingival massaging an age old practice is said to increase capillary gingival microcirculation, thereby increasing oxygen sufficiency, gingival fibroblastic proliferation, keratinization of oral and sulcuar epithelium, and formation of dense bundles of collagenous connective tissue all of which are attributable to creeping attachment[5,7]. Gingival massaging is carried out using various agents that aid lubrication as well as medication of the tissues. IrimedadiTaila an ayurvedicproductis said to have been used for centuries by many communities in the Middle East and North Africa as a massaging agent[8]. It consists mainly of Acacia arabica a complex mixture of the calcium, magnesium and potassium salts of Arabic acid. Its antiplaque properties are said to create right conditions for gingiva to recapture its biologic dimensions[5,8].

However no much of information is available upon an electronic or manual search concerning the effects of gingival massaging in the treatment of gingival recessions. There is a dearth of information as to by what exact mechanisms the non-surgical approaches help root coverage and to what extent if at all. Given that many patients are skeptical about surgical treatment, scaling/root planing followed by gingival massaging with an agent could be a better option provided their benefits are proved. This study is one such attempt to evaluate the effect of gingival massaging using an ayurvedic product in comparison with SCRF to assess the treatment outcomes in the management of Miller’s class I gingival recessions. Hence the aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy of SCRF and gingival massaging (by placebo and IrimedadiTaila) in terms of root coverage in Miller’s Class I recession, with respect to clinical parameters [Recession height (RH), recession width (RW), probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), thickness of keratinized tissue (TKT) and width of attached gingiva]. Further, intergroup which comparisons of treatment outcomes to assess advantages or disadvantages of one technique over the other was also assessed.

A total of 90 sites of Miller’s class-I gingival recessions on labial aspects of maxillary anteriors, were selected from the patients reporting to the out-patient department of Periodontics, Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore. Teeth associated with inadequate width of attached gingiva, caries/restorations were excluded. Pregnant females and individuals afflicted by systemic disease, tobacco/alcohol abuse, parafunctional habits were excluded from the study. Individuals who were already on the regimen of gingival massage or had undergone mucogingival surgery were dropped out of the study.

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Modern Dental College and Research Centre, Indore and study sites were randomly allocated to three different study groups after obtaining an informed consent. Group I (control group) comprised of 30 sites that were treated by massaging with placebo (clarified butter). Group II (test group) included 30 sites that were treated by massaging with an ayurvdicoil (IrimedadiTaila). Group III (test group) included 30 sites to be treated by SCRF[6].

The sites were subjected to clinical assessments as follows: RH was measured as the distance from the CEJ to the gingival margin (GM), calculated in millimeters. RW was recorded as horizontal width of CEJ. Probing pocket depth was measured as the distance from the GM to the bottom of the gingival sulcus. CAL was calculated as recession height and probing depth (RH + PD). Width of attached gingiva was recorded as the distance between the free gingival groove and the MGJ. All the readings were recorded using a manual pressure-sensitive periodontal probe DB 764 R, (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany) calibrated at a force of 0.2 N. Readings for TKT was obtained by penetrating the tissue with a 15 number endodontic spreader under lidocaine 15 gm spray and subsequently the penetration depth was measured with an electronic caliper of 0.01 mm resolution. The gingival thickness was assessed at midbuccal level in the attached gingiva, half way between the mucogingival junction and free gingival groove[9]. These readings were recorded pre-operatively as well as 6 mo post-operatively and then subjected to statistical analysis.

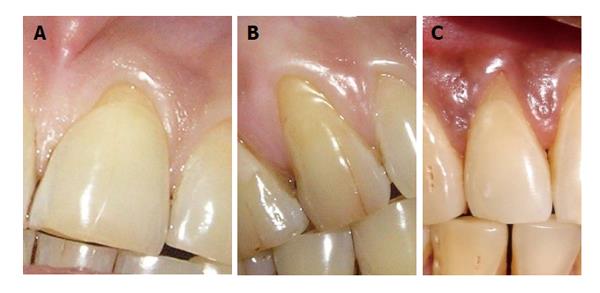

After a detailed examination and diagnosis, scrupulous oral prophylaxis was accomplished to ensure that local etiological factors are eliminated; followed by oral care instructions and patient motivation towards compliance. Patients belonging to group I (Figure 1A) and group II (Figure 1B) were trained to master the technique of gingival massaging with either of the agents as the case may be. The technique involved massaging their gums with finger three times daily for two minutes in the concerned area and then rinse away with water. Patients were instructed to comply with gingival massaging for the span of 6 mo, after which to report back for post-operative evaluation. Sites belonging to group III (Figure 1C) were treated surgically by semilunar coronally repositioned flap (Figure 2) as recommended by Tarnow[6], followed by suitable postoperative surgical care and oral care instructions. The patients were recalled at 1, 3 and 6 mo post operatively. One and 3 mo postoperative recall visits were utilized for reinforcement of oral care regimen and massaging techniques, wherein, readings at 6 mo postoperative follow up only were utilized for statistical analysis.

Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to test for the Normalcy of the data. The parameters significantly differed from normal distribution, and therefore, all the comparisons were tabulated using Non-Parametric tests, i.e., wilcoxon signed rank test, Kruskal Wallis and Mann Whitney U test. All comparisons were done using SPSS Statistical Software Package Version 10.0 and probability value (P-value) of less than 0.01 was considered as statistically significant.

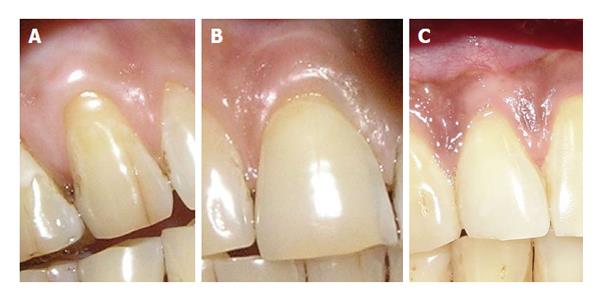

Gingival massaging with placebo (Ghee) (Figure 3A) resulted in a statistically significant reduction in probing pocket depth (P = 0.001), gain in clinical attachment level (P = 0.002) and increase in thickness of keratinized tissue (P < 0.001). The clinical improvements with respect to recession height, recession width and width of attached gingiva were statistically nonsignificant (Table 1). Gingival massaging using an ayurvedic product (IrimedadiTaila) (Figure 3B), on the contrary resulted in to statistically significant reductions in recession height and recession width (P < 0.003 and P < 0.001 respectively); also a significant gain in thickness of keratinized tissue and width of attached gingiva (P < 0.001) and (P = 0.001) respectively. But reductions in probing pocket depth and clinical attachment level were statistically nonsignificant (Table 2). Sites treated by semilunar coronally repositioned flap (Figure 3C) exhibited highly significant improvements with respect to all the clinical parameters except probing pocket depth (Table 3).

| Clinical parameters | Baseline (mean ± SD) | 6 mo (mean ± SD) | P-value (significance) |

| Recession height | 1.7 ± 0.65 | 1.5 ± 0.51 | 0.034 |

| Recession width | 3.8 ± 0.66 | 3.57 ± 0.63 | 0.100 |

| Probing pocket depth | 1.9 ± 0.40 | 1.5 ± 0.51 | 0.001b (S) |

| Clinical attachment level | 3.5 ± 0.82 | 3 ± 0.87 | 0.002b (S) |

| Thickness of keratinized tissue | 0.84 ± 0.18 | 0.97 ± 0.21 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Width of attached gingiva | 2.53 ± 0.57 | 2.8 ± 0.55 | 0.011 |

| Clinical parameters | Baseline (mean ± SD) | 6 mo (mean ± SD) | P-value (significance) |

| Recession height | 1.77 ± 0.63 | 1.27 ± 0.58 | 0.003b (S) |

| Recession width | 3.3 ± 0.46 | 2.23 ± 0.43 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Probing pocket depth | 1.47 ± 0.50 | 1.63 ± 0.49 | 0.096 (NS) |

| Clinical attachment level | 3.23 ± 0.82 | 2.9 ± 0.76 | 0.064 (NS) |

| Thickness of keratinized tissue | 0.85 ± 0.17 | 1.07 ± 0.19 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Width of attached gingiva | 2.37 ± 0.56 | 2.9 ± 0.66 | 0.001b (S) |

| Clinical parameters | Baseline | 6 mo | P-value |

| (mean ± SD) | (mean ± SD) | (significance) | |

| Recession height | 2.33 ± 0.55 | 0.57 ± 0.50 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Recession width | 3.33 ± 0.76 | 1.1 ± 0.66 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Probing pocket depth | 1.57 ± 0.50 | 1.33 ± 0.48 | 0.071 |

| Clinical attachment level | 3.87 ± 0.73 | 1.9 ± 0.66 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Thickness of keratinized tissue | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 1.38 ± 0.23 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Width of attached gingiva | 2.63 ± 0.71 | 3.37 ± 0.56 | 0.001 (S) |

Intergroup comparisons (Table 4) via Kruskal Wallis test aided in the determination of advantages of one technique over the other. Sites treated by SCRF exhibited highly significant improvements with respect to recession height (P < 0.001), recession width (P < 0.001), CAL (P < 0.001), thickness of keratinized tissue (P < 0.004) as compared to those treated by gingival massaging with the ayurvedic substance. However no significant difference was observed in relation to probing pocket depth between the groups (Table 5). Sites treated by SCRF had similar advantages when compared with sites treated by gingival massaging using a placebo (Table 6).

| Clinical parameter | Group I | Group II | Group III | χ2 | P-value (significance) |

| Recession height | 0.2 ± 0.48 | 0.5 ± 0.78 | 1.77 ± 0.73 | 47.56 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Recession width | 0.23 ± 0.77 | 1.07 ± 0.58 | 2.23 ± 0.82 | 51.28 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Probing pocket depth | 0.4 ± 0.49 | -0.17 ± 0.53 | 0.23 ± 0.68 | 13.29 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Clinical attachment level | 0.5 ± 0.73 | 0.33 ± 0.96 | 1.97 ± 0.81 | 42.01 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Thickness of keratinized tissue | -0.13 ± 0.12 | -0.23 ± 0.15 | -0.41 ± 0.27 | 22.86 | < 0.001b (S) |

| Width of attached gingiva | -0.27 ± 0.52 | - 0.53 ± 0.68 | -0.73 ± 0.98 | 7.03 | 0.03 (NS) |

When compared between gingival massaging with an ayurvedic substance and placebo, former showed remarkable improvements only with respect to recession width (P < 0.001), probing pocket depth (P < 0.001) and thickness of keratinized tissue (P < 0.001). However there was no significant difference with respect to CAL, recession height and width of keratinized gingiva (Table 7).

Gingival recession is a common condition whose extent and prevalence has been noted to increase with age. It has been estimated that 50% of the population has one or more sites with 1mm or more of such root exposure. This prevalence rate increases to 88% for individuals above 65 years of age[10].

Given the high prevalence rate of gingival recession defects among the general population, it is imperative that dental practitioners have an understanding of the etiology, complications and treatment options of the condition. Even in this era, when sophisticated techniques and materials are available, non-invasive approaches to treatment of recessions remain in practice with paramount importance. This study was carried out to assess the viability of surgical and non-surgical techniques for management of gingival recessions.

Numerous studies reported the efficacy and predictability of proposed surgical techniques. Several factors govern the selection of a surgical technique to treat recessed teeth such as the anatomy of the defect site, such as the size of the recession, width of keratinized tissue adjacent to the defect, dimensions of the interdental soft tissue, and the depth of the vestibule or the presence of frenula and evidence based predictability of various procedures[11-13]. The SCRF surgical procedure is easy to perform and highly reproducible in shallow recession defects (class I) when gingival augmentation is not needed. Case reports[2,14,15] have shown a high success rate for this procedure.

Gingival massaging, an age old traditional oral hygiene practice which has been used for centuries by many communities have two quite separate effects on gingival keratinization. One, the direct effect of frictional stimulation leading to an increased mitotic rate and greater thickness of both the malpighian region and the stratum corneum of the gingival epithelium and the other, an indirect effect of the more efficient removal of dental plaque which leads to a reduction in inflammation, allows the gingival epithelium to express more fully its keratinizing potential[16]. The other effects of gingival massaging is said to increase capillary gingival microcirculation[17,18] thereby increasing oxygen sufficiency[19], gingival fibroblastic proliferation[7], and formation of dense bundles of collagenous connective tissue[20]. However, only one case is available in the literature[21] showing successful root coverage at multiple sites resulting from gingival massage. To our knowledge, there have been no long term controlled studies to provide outcome assessment data with regard to predictability and percentage of recession coverage by gingival massaging using ayurvedicoil. Hence this study was undertaken to compare benefits of gingival massaging using ayurvedic oil with those of SCRF technique in the treatment of class I recession.

This study witnessed that, although SCRF technique proved to be far superior, the clinical outcomes of gingival massaging by an ayurvedic oil (IrimedadiTaila) were almost close to it (Tables 1, 2 and 3). Both the procedures produced statistically significant improvement with relation to recession height, recession width, thickness of keratinized tissue and width of attached gingiva, implying that both the methods are equivalent in root coverage and increasing width and thickness of attached gingiva. The significant root coverage achieved with of SCRF technique in the present study is almost in accordance with numerous other studies with only slight differences[12,22-26]. Some of those studies with higher success in root coverage have notably used additional methods of flap fixation such as sutures/adhesives or microsurgical techniques that may have enhanced clinical outcomes. Thus the differences in surgical protocols and measurement methods adapted in the study could be held responsible for variations in the results. The significant increase in width of attached gingiva with SCRF technique could be attributed to the granulation tissue that fills the semilunar area. Other studies too have presented similar observation although with slight variations[24,25,27-29]. This variability could be attributed to the bias in the methods used to identify the mucogingival position, surgical approach and improper case selection. The significant increase in the thickness of keratinized tissue in our study goes well in accordance with Bittencourt et al[26]. Increase in the thickness of gingival tissue is desirable since it can resist gingival recession resulting from faulty tooth brushing and inflammatory reactions[29,30]. But some authors have questioned the ability of thick gingival tissue in the prevention of recession. Based on a 2 year prospective clinical study authors recommend the practice of correct brushing technique to prevent recession instead of relying on the ability of thickness of gingiva[31]. Only long term follow up studies can determine the sound basis for this association. SCRF technique also leads to significant gain in CAL in the study sample. Similar observations have been reported by other studies too[24,26,32]. The probing depth reductions were non-significant.

In this study, an attempt was made to elucidate the role of creeping attachment in root coverage following gingival massaging with ayurvedic oil. Gain in CAL was assumed to be reflecting creeping attachment but the gain in CAL following gingival massaging were negligible (0.4-0.89 mm) and statistically non-significant (Table 2). These results are weak to support the hypothesis that, gingival massaging brings root coverage via creeping attachment. The available literature also lacks exact details as to when and how the creeping attachment starts and progresses. Certain studies have observed that creeping attachment occurs between 1 mo to 1 year.

In contrast, there was increase in the probing depths although negligible. This leads us to speculate that, massaging action may have lead to flattening and adaptation of gingival margin, or even marginal hypertrophy that majorly attributes to reduction in width and height of visible recession. Though this speculation may not hold strong consideration, it cannot be denied.

Intergroup comparisons (Table 4) demonstrated clear advantages of SCRF over gingival massaging with ayurvedic oil, which inturn is advantageous over gingival massaging with placebo (clarified butter). This clearly states the superior nature of SCRF in the treatment of class I recessions, while, gingival massaging with ayurvedic oil maintains close proximity to SCRF in terms of its clinical outcomes. Unfortunately no such data is available in the literature against which our observations could be compared.

Nevertheless SCRF procedure is a gold standard approach in terms of all the clinical parameters except for probing pocket depth and width of attached gingiva compared to the gingival massaging group. Under the circumstances where SCRF procedure remains contraindicated, or in patients who are skeptical on having to undergo surgical therapy for recession coverage, gingival massaging with an ayurvedic substance (IrimedadiTaila) offers a best alternative with almost equivalent benefits. Even the simple gingival massaging using an inert lubricant (such as Ghee) can be opted for as an adjunct to Scaling and root planing in areas of recession during maintenance phase.

The Semilunar coronally repositioned flap (SCRF) is one of the procedure described in the Journal of Clinical Periodontology in 1986 for the treatment of shallow recession. So far, however, no controlled clinical study has evaluated the SCRF performed as originally described and compared it with gingival massaging using an Ayurvedic product.

Root coverage was achieved in both the groups and was stable during the evaluation period of 6 mo.

This is the pioneer study, where authors have used Ayurvedic product for massaging and results were significant when compared with SCRF technique.

Daily home care by the patient and gingival massaging might play an important role in improving gingival recessions and prevents further progression of mucogingival defects.

IrimedadiTaila: Name of Ayurvedic massaging oil, with ingrediants like Acacia Arabica, etc., which is used for maintaining plaque free environment in the oral cavity.

The authors have chosen a very interesting and inexhaustible theme for the article.

P- Reviewer: Mishra AK, Pejcic A, Zucchelli G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H. The natural history of periodontal disease in man: prevalence, severity, and extent of gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1992;63:489-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bouchard P, Malet J, Borghetti A. Decision-making in aesthetics: root coverage revisited. Periodontol 2000. 2001;27:97-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Miller PD. A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Clauser C, Nieri M, Franceschi D, Pagliaro U, Pini-Prato G. Evidence-based mucogingival therapy. Part 2: Ordinary and individual patient data meta-analyses of surgical treatment of recession using complete root coverage as the outcome variable. J Periodontol. 2003;74:741-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aimetti M, Romano F, Peccolo DC, Debernardi C. Non-surgical periodontal therapy of shallow gingival recession defects: evaluation of the restorative capacity of marginal gingiva after 12 months. J Periodontol. 2005;76:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tarnow DP. Semilunar coronally repositioned flap. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:182-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Horiuchi M, Yamamoto T, Tomofuji T, Ishikawa A, Morita M, Watanabe T. Toothbrushing promotes gingival fibroblast proliferation more effectively than removal of dental plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:791-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gazi MI. The finding of antiplaque features in Acacia Arabica type of chewing gum. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18:75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Goaslind GD, Robertson PB, Mahan CJ, Morrison WW, Olson JV. Thickness of facial gingiva. J Periodontol. 1977;48:768-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kassab MM, Cohen RE. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zucchelli G, Testori T, De Sanctis M. Clinical and anatomical factors limiting treatment outcomes of gingival recession: a new method to predetermine the line of root coverage. J Periodontol. 2006;77:714-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haghighati F, Mousavi M, Moslemi N, Kebria MM, Golestan B. A comparative study of two root-coverage techniques with regard to interdental papilla dimension as a prognostic factor. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2009;29:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kerner S, Sarfati A, Katsahian S, Jaumet V, Micheau C, Mora F, Monnet-Corti V, Bouchard P. Qualitative cosmetic evaluation after root-coverage procedures. J Periodontol. 2009;80:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Thompson BK, Meyer R, Singh GB, Mitchell W. Desensitization of exposed root surfaces using a semilunar coronally positioned flap. Gen Dent. 2000;48:68-71; quiz 72-73. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Casati MZ, Nociti FH jr, SallumEnilson A. Treatment of gingival recessions by semilunar coronally positioned flap. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent. 2001;55:169-172. |

| 16. | Ekuni D, Yamanaka R, Yamamoto T, Miyauchi M, Takata T, Watanabe T. Effects of mechanical stimulation by a powered toothbrush on the healing of periodontal tissue in a rat model of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:45-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hanioka T, Nagata H, Murakami Y, Tamagawa H, Shizukuishi S. Mechanical stimulation by toothbrushing increases oxygen sufficiency in human gingivae. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:591-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Perry DA, McDowell J, Goodis HE. Gingival microcirculation response to tooth brushing measured by laser Doppler flowmetry. J Periodontol. 1997;68:990-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tanaka M, Hanioka T, Kishimoto M, Shizukuishi S. Effect of mechanical toothbrush stimulation on gingival microcirculatory functions in inflamed gingiva of dogs. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:561-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fraleigh CM. Tissue changes with manual and electric brushes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1965;70:380-387. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Ando K, Ito K, Murai S. Improvement of multiple facial gingival recession by non-surgical and supportive periodontal therapy: a case report. J Periodontol. 1999;70:909-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Marggraf E. A direct technique with a double lateral bridging flap for coverage of denuded root surface and gingiva extension. Clinical evaluation after 2 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jahangirnezhad M. Semilunarcoronally repositioned flap for the treatment of gingival recession with and without tissue adhesives: a pilot study. J Dent (Tehran). 2006;3:36-39. |

| 24. | Bittencourt S, Del Peloso Ribeiro E, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Nociti FH, Casati MZ. Comparative 6-month clinical study of a semilunar coronally positioned flap and subepithelial connective tissue graft for the treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol. 2006;77:174-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bittencourt S, Ribeiro Edel P, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Nociti FH, Casati MZ. Root surface biomodification with EDTA for the treatment of gingival recession with a semilunar coronally repositioned flap. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1695-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bittencourt S, Ribeiro Edel P, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Nociti FH, Casati MZ. Semilunar coronally positioned flap or subepithelial connective tissue graft for the treatment of gingival recession: a 30-month follow-up study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1076-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pini Prato G, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Magnani C, Cortellini P, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1992;63:919-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rosetti EP, Marcantonio RA, Rossa C, Chaves ES, Goissis G, Marcantonio E. Treatment of gingival recession: comparative study between subepithelial connective tissue graft and guided tissue regeneration. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1441-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Müller HP, Stahl M, Eger T. Root coverage employing an envelope technique or guided tissue regeneration with a bioabsorbable membrane. J Periodontol. 1999;70:743-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Paolantonio M, Dolci M, Esposito P, D’Archivio D, Lisanti L, Di Luccio A, Perinetti G. Subpedicle acellular dermal matrix graft and autogenous connective tissue graft in the treatment of gingival recessions: a comparative 1-year clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1299-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wennström JL, Zucchelli G. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures? A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Santana RB, Mattos CM, Dibart S. A clinical comparison of two flap designs for coronal advancement of the gingival margin: semilunar versus coronally advanced flap. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |