Published online Aug 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.106941

Revised: April 15, 2025

Accepted: May 13, 2025

Published online: August 26, 2025

Processing time: 97 Days and 9.8 Hours

Bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for severe obesity but is associated with an increased risk for development of eating disorders. Indeed, numerous maladaptive eating behaviors and eating disorders have been described following bariatric surgery. However, the differentiation of pathologic eating patterns from expected dietary changes following bariatric surgery can sometimes be difficult to discern.

A female in her early 40s presented for medical stabilization of severe protein calorie malnutrition after losing 52.3 kg over the last six months after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, with subsequent development of cyclic nausea and vomiting. Fear of these aversive physical symptoms led to further restriction of nutritional intake and weight loss. The patient was diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, which has not been previously reported after bariatric surgery.

Improvement in the diagnostic nomenclature for feeding and eating disorders is warranted for patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.

Core Tip: Eating behaviors after bariatric surgery may lack specific nomenclature and/or not meet the diagnostic criteria for the currently recognized feeding and eating behaviors in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition. Many individuals who have undergone bariatric surgery seemingly meet criteria for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder but this diagnosis may not be considered due to the body dysmorphia that many individuals experience in relation to bariatric surgery. Improvements in the assessment and categorization of disordered eating habits following bariatric surgery are warranted to improve post-operative outcomes.

- Citation: Cass K, Leggett A, Gibson DG. Diagnostic dilemma of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder after bariatric surgery: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(24): 106941

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i24/106941.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.106941

Bariatric surgery is considered the most effective method for lasting weight loss and improvement of obesity-related comorbid conditions[1,2]. Bariatric surgery contributes to weight loss through various mechanisms: (1) Limiting the amount of food that can be ingested, as seen in “restrictive procedures”, such as the gastric sleeve; (2) Intestinal malabsorption, which results from procedures such as jejunoileal bypass; and (3) Due to numerous post-surgical physiologic adaptations that impact eating behaviors[3]. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), one of the most commonly performed bariatric surgeries, causes both limited nutritional intake and malabsorption.

However, research also indicates that nearly 40% of individuals develop problematic eating behaviors following bariatric surgery[4], and between 1.0%-4.5% of individuals develop a full-blown eating disorder following bariatric surgery[5,6], both of which are associated with worse bariatric surgery outcomes[7,8]. Many of the disordered eating behaviors described in the literature are associated with bingeing and purging behaviors, although restricting behaviors, including atypical anorexia nervosa, are less frequently described[9,10]. The reasons that disordered eating can develop following surgery are largely unknown but could result from: learned restrictive behaviors; the development of ritualized eating patterns; maladaptive compensatory strategies, such as vomiting, to address discomfort and anxiety; and potentially due to contribution from the weight loss itself[9].

The development of disordered eating behaviors following weight loss itself can be better understood in the context of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment, a landmark study conducted by Ancel Keys in the 1940s[11]. The experiment, which subjected participants to prolonged caloric restriction, demonstrated that extreme weight loss and malnutrition causes physiological and psychological distress—individuals developed obsessive thoughts about food, anxiety and emotional disturbances developed, and disordered eating behaviors including binge eating and purging developed.

Many of these findings may be explained by the concept of weight suppression, or the difference between the current body weight and the highest historical weight, which has numerous metabolic, physiological and psychological implications. Research in both healthy individuals and those with a history of eating disorders suggests an association between greater weight suppression and risk for development of disordered eating, as well as bingeing and purging behaviors[12]. Greater weight suppression, as well as more aggressive rates of weight loss, are predictive of medical complications commonly associated with malnutrition[13-15]. Rapid weight loss can also result in significant body dissatisfaction and shame (due to loose skin), leading to increased psychological distress and impairment[16].

Disordered eating behaviors may also develop due to the recommended post-surgical dietary habits that can include: Learned restrictive behaviors and/or compensatory behaviors. Dietary recommendations following bariatric surgery can contribute to maladaptive eating behaviors and generally include: Taking smaller bites, consuming 4-6 meals throughout the day, chewing the food extremely well, and avoiding consumption of high-calorie dense foods and simple sugars that can cause malabsorption and dumping syndrome[17]. Loss of control eating is a subjective experience in which individuals report a loss of control over the food consumed, affecting around 25% of individuals[18,19]. Many patients will also report grazing behaviors, or the continued consumption of food throughout the day. Plugging is a disordered eating pattern that results in vomiting due to the volitional consumption of dry foods or poorly chewing foods, resulting in food getting stuck in the esophagus due to the much smaller stomach opening post-surgery; this affects a large majority of individuals after RYGB[18]. Dumping syndrome results from the consumption of sweets or highly-caloric, volume-dense foods that cause rapid emptying of hyperosmolar chyme into the small intestine and development of malabsorption with diarrhea; this affects a majority of individuals within two years after RYGB[18]. Chewing and spitting behaviors are also frequently described after bariatric surgery as a means to avoid consequences of nutritional intake, including weight gain, plugging, and/or dumping syndrome; similarly, self-induced vomiting becomes more prominent after bariatric surgery[20]. However, these problematic eating behaviors lack specific nomenclature and are not recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR)[21].

Other feeding and eating disorders described after bariatric surgery are recognized by the DSM, 5th edition and include anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), atypical AN, binge eating disorder (BED), and night eating syndrome[10,21,22]. BED has been described as developing “de novo” following surgery, and atypical AN, with symptoms including preoccupation with food and weight, purposeful food restriction, and phobia of weight gain, has repeatedly been described following bariatric surgery[10,23,24]. However, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), characterized by significant weight loss, nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements, but with no body image disturbance or over-valuation of weight or shape, has not been described in the literature following bariatric surgery.

ARFID causes marked clinical impairment and can manifest in three primary ways: Avoidance of food due to sensory sensitivities, fear of negative consequences (such as choking, pain, nausea, vomiting, or other gastrointestinal distress), or a general lack of interest in eating[21]. Avoidance of food due to feared consequences of eating is the most common contributor toward development of ARFID in adults requiring inpatient treatment. Rigby described a woman with food avoidance after bariatric surgery who ultimately did not meet criteria for ARFID due to her engagement in self-induced vomiting (to relieve plugging and provide a sense of control), although she met many of the other diagnostic criteria for ARFID[25]. As such, it is odd that there are no reports of ARFID developing after surgery, given that aversive conse

The following case study of a patient who developed eating disorder symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of ARFID after bariatric surgery demonstrates the development of disordered eating behaviors after bariatric surgery and elucidates some of the limitations of the existing DSM-5-TR nosological categories to properly classify eating disordered behaviors following bariatric surgery.

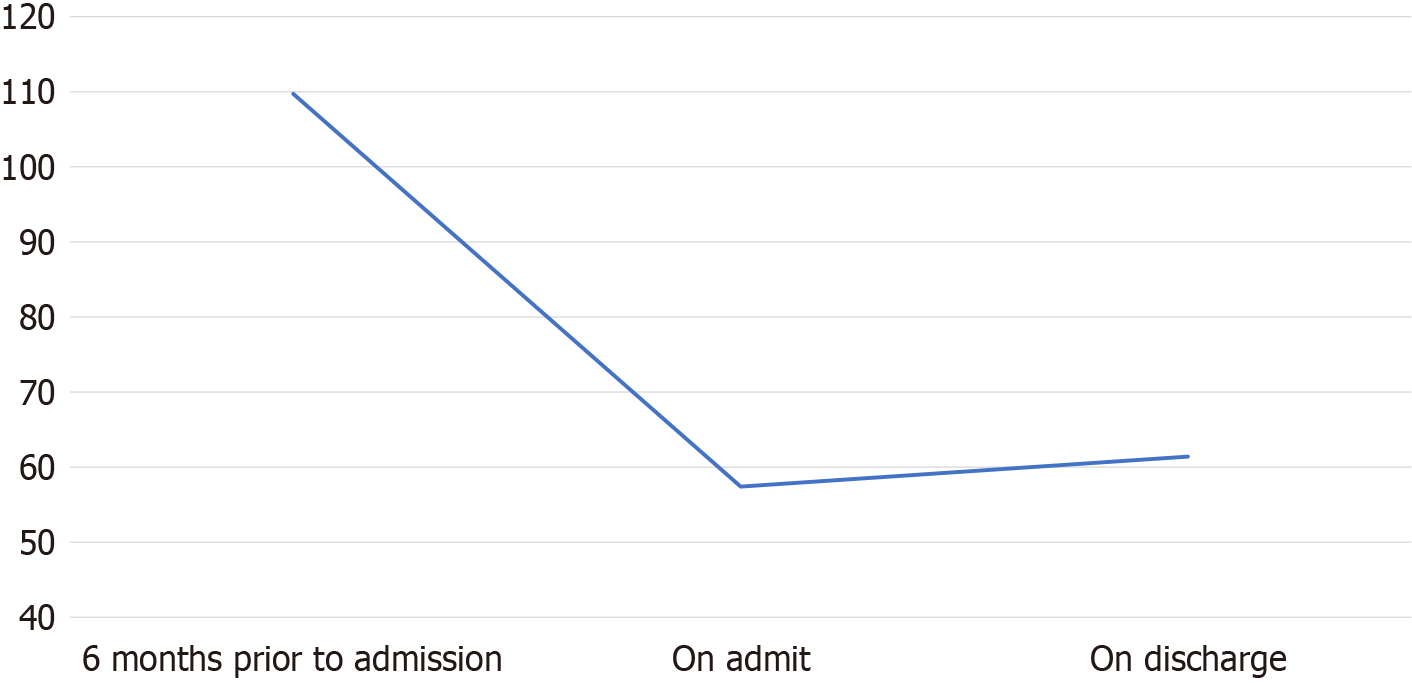

A female in her early 40s was admitted to our specialized inpatient unit for medical stabilization for severe protein calorie malnutrition after losing 52.3 kg over the last six months (Figure 1).

The patient had undergone RYGB approximately six months prior to this hospital admission, with complications of iatrogenic small bowel obstruction and peptic ulcer disease, and subsequent development of cyclic nausea and vomiting with unintentional weight loss. The patient reported gradually worsening nausea to the point that she felt nauseous at the smell, sight, or even thought of food, and reported that involuntary vomiting, though intermittent, felt uncontrollable. Prior to surgery, the patient reported that she “loved food”, but that eating “felt dangerous” following surgery, and she feared that food would harm her body.

Due to the aversive physical experiences (nausea and vomiting) following eating, and resultant avoidance of food, the patient’s weight continued to decline. She stopped all oral nutrition and was admitted on 100% enteral feeding, reporting extreme fear at the thought of trying oral nutrition. Her last upper endoscopy was completed about three months before her current presentation and showed a healed marginal ulcer with otherwise patent anatomical changes. The patient denied fear of weight gain or engaging in any compensatory behaviors to lose weight.

The patient denied any disordered eating or food aversion prior to surgery and denied any history of an eating disorder. She did have a history of anxiety pre-dating the bariatric surgery but reported that this had significantly worsened in the setting of her weight loss.

Personal history was significant for morbid obesity (highest ever weight of 109.7 kg), hypertension, and migraines, with improvement of hypertension after the bariatric surgery. There was no family history of any eating disorders.

Upon admission, the patient was 57.4 kg (height 5’2”; 115% of normal body weight, body mass index of 23 kg/m2) with the following vitals: Temperature 36.8 Celsius, blood pressure 135/95 mmHg (normalized the following morning to 102/70 mmHg), heart rate 81 beats per minute, and 99% oxygen saturation on room air. Mucous membranes were dry, and she had a few healed scars in her abdominal region.

Psychiatric state examination: The patient appeared adequately groomed with multiple layers of clothing. She appeared anxious and did not exhibit any psychomotor agitation. Speech, cognition, attention, and thought processes were all appropriate, although there was limited insight and judgement into the severity of her illness. The patient met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and endorsed feeling nervous, reported an inability to stop worrying, reported fear that something awful might happen, and endorsed feelings of restlessness and irritability. Though the diagnosis of GAD pre-dated surgery, the patient reported an increase in anxiety symptoms and a recent onset of panic attacks, all related to her fear of experiencing pain, nausea, or vomiting after eating. The patient did not endorse other co-morbid psychiatric disorders and denied fear of weight gain, drive for thinness, intentional self-induced vomiting, or engaging in compensatory behaviors to lose weight. The patient did endorse body image disturbance and dissatisfaction, stating “I feel mad that I don’t recognize my body”, and noted that the rapidity of weight loss and change in the experience of her body “was alarming”. The patient denied any contribution of body dysmorphia toward her eating behaviors but noted that her poor body image impacted her mood and self-esteem.

Pertinent laboratory values on admission showed starvation hepatitis (aspartate aminotransferase of 171, alanine aminotransferase of 163), hypoalbuminemia (2.6 g/dL), hypokalemia (potassium 2.8 mmol/L), hypomagnesemia (1.3 mEq/L), normocytic anemia (hemoglobin of 11.6 g/dL), and a low prealbumin of 14.4 mg/dL.

No special notes.

Severe protein calorie malnutrition secondary to ARFID.

Our specialized multidisciplinary team, including medical and psychiatric physicians, registered dieticians, psychologists, social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and nursing support, provided inpatient medical stabilization for her malnutrition and associated medical and psychiatric complications. She was provided pharmacologic support for both nausea and anxiety, the latter treated with her home sertraline dose of 50 mg daily and with the addition of as needed hydroxyzine and lorazepam. The patient underwent correction of electrolyte abnormalities and was closely monitored for development of refeeding hypophosphatemia and other potential early refeeding complications.

Psychologic treatment entailed cognitive behavioral therapy adapted for ARFID[27], with the goal of introducing progressive oral nutrition and reducing anxiety over time. Psychoeducation about ARFID was introduced by the entire team, with particular emphasis on the association between avoidance and increased anxiety over time and how exposure works to reduce anxiety through the correction of erroneous and mal-adaptive beliefs about the dangerousness of eating. The physician emphasized that taking in oral nutrition would not harm the body and that physical pain was likely due to malnutrition, which would improve with time.

The patient worked with the dietitian and psychologist to create a fear and avoidance hierarchy of foods, from least to most anxiety-provoking. Graded exposure to food started with the patient receiving self-chosen foods for comfort, given at mealtimes, and with no initial expectation of oral completion. The patient expressed fear of vomiting, which was normalized in the context of ARFID. Eliciting the patient’s own motivation to engage in exposure work, “I just want to be able to live again, to stand and cook; I want my life back” was a core intervention across the team of providers.

The patient gradually began to incorporate required oral nutrition, with increases in prescribed oral nutrition occurring at stepped intervals. The patient was typically successful in completing, although there were several instances in which the patient did not complete due to intolerance of fullness and nausea or fear of emesis. The occupational therapist and psychologist worked with the patient to develop coping strategies for nausea, including incorporation of yoga for digestion. They also encouraged the patient to continue to increase oral intake despite negative physical consequences of eating, focusing on improving distress tolerance of aversive physical sensations.

With ongoing psychological support and encouragement to increase oral intake and challenge fears related to eating, the patient was tolerating 50% orals and 50% enteral nutrition at the time of discharge, consuming a weight maintenance meal plan of 1600 kcal. She reported that she was proud of the progress she had made, noting that the same foods that she feared even smelling were foods that she was now able to eat, though nausea and occasional involuntary vomiting continued. As expected, there was no improvement in the body image disturbance given the relatively short length of stay for medical stabilization (15 days). She discharged at 61.4 kg (Figure 1 for her weight trend).

Patient was discharged to a residential treatment center for continued behavioral health treatment of her eating disorder.

This patient’s clinical presentation was most captured by the ARFID diagnosis, specifically due to the fear of aversive consequences[28]. In this case, negative experiences with eating (e.g., nausea and vomiting) lead to overgeneralized negative predictions about eating (“Every time I eat, I vomit”), resulting in food avoidance and weight loss. Indeed, the patient’s problematic eating behaviors likely developed in the context of fear conditioning[29], wherein eating food, a normally pleasant activity, was repeatedly paired with the aversive and painful experience of nausea and vomiting following surgery, thereby increasing anxiety and the urge to limit nutritional intake. As the fear generalized to other stimuli (in this case, the sight, smell, and thought of food), anxiety increased, resulting in almost total food avoidance and rendering the patient unable to provide herself with life-saving nutrition. As this patient underwent graded exposure to oral nutrition and discovered that she could tolerate food and not be harmed, the patient’s fear of the dangerousness of food decreased due to inhibitory learning[30]. New, adaptive beliefs related to self-efficacy with eating and tolerating distress emerged, and the willingness to eat improved despite continued nausea and the potential for vomiting.

Similar fear-based avoidance of eating may develop as a result of other experienced complications as well, such as dumping syndrome, which can be associated with nausea, dizziness, and diarrhea, as food rapidly empties into the small intestine. Individuals with pre-existing anxiety or sensory sensitivities may be especially prone to develop food restriction. However, the point at which these disordered eating behaviors transition from maladaptive, yet expected, eating behaviors to pathological disordered eating following bariatric surgery can be difficult to discern. Many bariatric patients experience nausea, vomiting or pain when consuming certain foods, which may lead to conditioned food aversion. For some, this avoidance becomes so severe that they limit their food intake to a dangerously low level, leading to nutritional deficiencies, significant weight loss beyond healthy levels, and increased psychological distress[31].

Although ARFID captured many of this patient's symptoms, some of the unique emotional responses and disordered eating behaviors observed following bariatric surgery arguably do not fit into existing DSM-5 eating disorder categories, and, therefore, are at risk of being overlooked. For example, this patient reported body image disturbance (“I feel mad that I don’t recognize my body”), which is typically an exclusionary symptom for diagnosing ARFID, even though the patient’s reasons for food avoidance clearly resided in the ARFID conceptualization, and the body dysmorphia did not contribute to the observed eating behaviors in this case. As many patients report body dissatisfaction due to hanging or redundant skin following bariatric surgery[10], acknowledgement that body image distress can occur for reasons other than fear of weight gain or dissatisfaction with weight, would likely improve treatment effectiveness[9].

Though this patient did not report self-induced vomiting, this behavior occurs in 7% of bariatric surgery patients during their first year following surgery[18,20], and were it present, would further complicate diagnosing the patient with ARFID. Self-induced vomiting is currently classified as a compensatory behavior in those with BN and also for those with a diagnosis of AN, binge eating/purging subtype. However, patients who have undergone bariatric surgery may report engaging in self-induced vomiting as a means to reduce pain from plugging or to relieve nausea as opposed to increase weight loss[20]. As vomiting is not currently considered in the diagnostic criteria of ARFID, patients may be misdiagnosed with AN-BP and subsequently not receive evidence-based treatment to address the actual drivers of their behaviors. Further, following surgery, patients may have volitional vomiting that could have deleterious consequences, as excessive vomiting can result in numerous medical complications, including death[32].

An argument for expanding the ARFID inclusion criteria has previously been proposed[25], suggesting the need to account for: (1) Body image distress uniquely related to rapid weight loss, including anxiety related to the physical consequences of sudden weight loss, and a disturbance to one’s sense of identity with the sudden transition to a much smaller body; and (2) Self-induced vomiting for reasons other than weight control. In addition to a lack of general data on this subject, drawbacks to expanding the DSM-5 criteria for ARFID would include the risk of misdiagnosing atypical AN cases as ARFID if the reasons for body image disturbance are not carefully considered, and over-diagnosing an eating/feeding disorder in individuals who otherwise are experiencing normal but aversive transitory physical and psychological phenomena following bariatric surgery[33]. Regarding future directions, exploration into body dysmorphia in ARFID patients would be beneficial, as research in this area is limited and has historically focused on individuals with a drive for thinness in addition to ARFID[34], rather than distress from drastic weight loss. Additionally, large-scale prospective studies to determine the prevalence and risk factors for ARFID and other eating disorders following bariatric surgery would provide valuable data and contribute to the development of more effective diagnostic tools and treatment strategies.

As the number of bariatric surgery procedures performed in the United States continues to grow[35], improvements in the assessment and categorization of symptoms within the categorization of feeding and eating disorders in the DSM would arguably allow for better identification and treatment of patients who develop post-surgical disordered eating, improving postoperative outcomes and quality of life.

| 1. | Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, Aminian A, Angrisani L, Cohen RV, De Luca M, Faria SL, Goodpaster KPS, Haddad A, Himpens JM, Kow L, Kurian M, Loi K, Mahawar K, Nimeri A, O'Kane M, Papasavas PK, Ponce J, Pratt JSA, Rogers AM, Steele KE, Suter M, Kothari SN. 2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18:1345-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 378] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lingvay I, Cohen RV, Roux CWL, Sumithran P. Obesity in adults. Lancet. 2024;404:972-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 75.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Al-Najim W, Docherty NG, le Roux CW. Food Intake and Eating Behavior After Bariatric Surgery. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:1113-1141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Conceição EM, Mitchell JE, Pinto-Bastos A, Arrojado F, Brandão I, Machado PPP. Stability of problematic eating behaviors and weight loss trajectories after bariatric surgery: a longitudinal observational study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1063-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Alghamdi SA, Al Jaffer MA, Almesned RA, Alanazi SD, Alhnake AW, Alkhammash SM, Baabbad NM. Prevalence and factors influencing eating disorders among post-bariatric surgery patients in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2025;30:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kalarchian MA, King WC, Devlin MJ, Hinerman A, Marcus MD, Yanovski SZ, Mitchell JE. Mental disorders and weight change in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 7 years of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15:739-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El Ansari W, Elhag W. Weight Regain and Insufficient Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: Definitions, Prevalence, Mechanisms, Predictors, Prevention and Management Strategies, and Knowledge Gaps-a Scoping Review. Obes Surg. 2021;31:1755-1766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lopes KG, Romagna EC, Mattos DMF, Kraemer-Aguiar LG. Disordered Eating Behaviors and Weight Regain in Post-Bariatric Patients. Nutrients. 2024;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marino JM, Ertelt TW, Lancaster K, Steffen K, Peterson L, de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE. The emergence of eating pathology after bariatric surgery: a rare outcome with important clinical implications. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Conceição E, Orcutt M, Mitchell J, Engel S, Lahaise K, Jorgensen M, Woodbury K, Hass N, Garcia L, Wonderlich S. Eating disorders after bariatric surgery: a case series. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:274-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Keys A, Brožek J, Henschel A, Mickelsen O, Taylor HL. The Biology of Human Starvation. In: Simonson E, Skinner AS, Wells SM, Drummond JC, Wilder RM, King CG, Robert R, edits. Williams University of Minnesota Press, 1950; 763. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Gorrell S, Reilly EE, Schaumberg K, Anderson LM, Donahue JM. Weight suppression and its relation to eating disorder and weight outcomes: a narrative review. Eat Disord. 2019;27:52-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gibson D, Stein A, Khatri V, Wesselink D, Sitko S, Mehler PS. Associations between low body weight, weight loss, and medical instability in adults with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57:869-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Johannsen DL, Knuth ND, Huizenga R, Rood JC, Ravussin E, Hall KD. Metabolic slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2489-2496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Swenne I, Parling T, Salonen Ros H. Family-based intervention in adolescent restrictive eating disorders: early treatment response and low weight suppression is associated with favourable one-year outcome. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bennett BL, Grilo CM, Alperovich M, Ivezaj V. Body Image Concerns and Associated Impairment Among Adults Seeking Body Contouring Following Bariatric Surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sherf Dagan S, Goldenshluger A, Globus I, Schweiger C, Kessler Y, Kowen Sandbank G, Ben-Porat T, Sinai T. Nutritional Recommendations for Adult Bariatric Surgery Patients: Clinical Practice. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:382-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | de Zwaan M, Hilbert A, Swan-Kremeier L, Simonich H, Lancaster K, Howell LM, Monson T, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18-35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yu Y, Kalarchian MA, Ma Q, Groth SW. Eating patterns and unhealthy weight control behaviors are associated with loss-of-control eating following bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2021;17:976-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Parsons MA, Clemens JP. Eating disorders among bariatric surgery patients: The chicken or the egg? JAAPA. 2023;36:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). 2022. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Williams-Kerver GA, Steffen KJ, Mitchell JE. Eating Pathology After Bariatric Surgery: an Updated Review of the Recent Literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Smith KE, Orcutt M, Steffen KJ, Crosby RD, Cao L, Garcia L, Mitchell JE. Loss of Control Eating and Binge Eating in the 7 Years Following Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2019;29:1773-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hebebrand J, Antel J, Conceição E, Matthews A, Hinney A, Peters T. What Amount of Weight Loss Can Entail Anorexia Nervosa or Atypical Anorexia Nervosa After Bariatric Surgery? Int J Eat Disord. 2024;57:2461-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rigby A. Transdiagnostic Approach to Food Avoidance After Bariatric Surgery: A Case Study. CCS. 2018;17:280-295. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Conceição E, Mitchell JE, Vaz AR, Bastos AP, Ramalho S, Silva C, Cao L, Brandão I, Machado PP. The presence of maladaptive eating behaviors after bariatric surgery in a cross sectional study: importance of picking or nibbling on weight regain. Eat Behav. 2014;15:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thomas JJ, Wons OB, Eddy KT. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bourne L, Bryant-Waugh R, Cook J, Mandy W. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: A systematic scoping review of the current literature. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dunsmoor JE, Paz R. Fear Generalization and Anxiety: Behavioral and Neural Mechanisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:336-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, Zbozinek T, Vervliet B. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behav Res Ther. 2014;58:10-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1356] [Cited by in RCA: 1257] [Article Influence: 114.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Conceição EM, Utzinger LM, Pisetsky EM. Eating Disorders and Problematic Eating Behaviours Before and After Bariatric Surgery: Characterization, Assessment and Association with Treatment Outcomes. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:417-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Omalu BI, Ives DG, Buhari AM, Lindner JL, Schauer PR, Wecht CH, Kuller LH. Death rates and causes of death after bariatric surgery for Pennsylvania residents, 1995 to 2004. Arch Surg. 2007;142:923-8; discussion 929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stunkard AJ, Stinnett JL, Smoller JW. Psychological and social aspects of the surgical treatment of obesity. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143:417-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Barney A, Bruett LD, Forsberg S, Nagata JM. Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and Body Image: a case report. J Eat Disord. 2022;10:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Clapp B, Ponce J, Corbett J, Ghanem OM, Kurian M, Rogers AM, Peterson RM, LaMasters T, English WJ. American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery 2022 estimate of metabolic and bariatric procedures performed in the United States. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2024;20:425-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |