Published online Aug 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.106827

Revised: April 27, 2025

Accepted: May 13, 2025

Published online: August 26, 2025

Processing time: 100 Days and 14 Hours

Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS), caused by group A Streptococcus

A 69-year-old female on dual immunosuppressive regimen with mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus due to liver transplantation in 2010 and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department after tripping at home and injuring her neck with a wooden splinter from a chair. She developed progressive neck swelling and erythema with a diffuse maculopapular rash. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed a multiloculated neck abscess (59 mm × 32 mm × 85 mm). Her leucocyte count was 22.4 × 109/L, C-reactive protein 327.4 mg/L, and creatinine 233 μmol/L. Microbiological analysis tested positive for group A Streptococcus, suggesting diagnosis of STSS. She developed hypotension, dyspnea and fever prompting an urgent surgical drainage. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued, tacrolimus was reduced and was treated with cephazolin and clindamycin. Her skin rash slowly resolved, C-reactive protein decreased to 53.0 mg/L and kidney function improved. A computed tomography scan confirmed resolution and showed no new abscess formation. After two years of follow-up, she is unremarkable.

STSS in organ transplant recipients demands rapid managing of infections while minimizing the risk of graft rejection.

Core Tip: Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in organ transplant recipients is challenging and demands managing infections while minimizing the risk of graft rejection by modifying immunosuppressive therapy. This case highlights the importance of rapid interventions for infection control in patients after liver transplantation.

- Citation: Domislović V, Sremac M, Kosuta I, Sesa V, Jovic A, Grsic K, Papic N, Mrzljak A. Managing toxic shock syndrome in immunosuppressed patient after liver transplantation from trauma to triumph: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(24): 106827

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i24/106827.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i24.106827

Group A Streptococcus (GAS), or Streptococcus pyogenes, is aerobic gram-positive coccus that can lead to a variety of infections. On a global scale, GAS represents an important cause of morbidity and mortality, mainly affecting less developed countries[1]. While it is most frequently associated with non-invasive conditions like pharyngitis or superficial skin and soft tissue infections, it can occasionally lead to invasive GAS. Invasive GAS infection occurs when the bacteria are identified in areas of the body that are normally sterile, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or joint fluid. These infections may include necrotizing soft tissue infections, pregnancy-related complications, bloodstream infections, and respiratory tract infections with one of the most severe complications being streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS)[2,3]. Organ transplant recipients represent a particularly vulnerable population due to their chronic immunosuppressive therapy which impair their immune response. While critical for graft survival, immunosuppression increases susceptibility to infections, which are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality after liver transplantation, further compli

A 69-year-old female presented to the emergency department with progressive neck swelling with purulent secretion, along with a diffuse maculopapular rash extending across her trunk, back and extremities. She was reporting fatigue with mild dyspnea and initially had no fever.

Five days prior patient tripped at home and injured her neck with a wooden splinter from a chair.

Patient underwent liver transplantation in 2010 for primary biliary cholangitis. Her medical history included chronic kidney disease along with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and history of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. In the period following liver transplantation patient demonstrated stable graft function. Her immunosuppressive regimen included prolonged release tacrolimus at a dose of 2.5 mg daily and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) at a dose of 250 mg twice daily. Other medications included pantoprazol, amlodipine, long and short acting insulin and alopurinol. Her renal function was chronically impaired with a baseline creatinine level of 173 μmol/L and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 26 mL/minute/1.73 m2, attributed to combination of calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Recent tacrolimus levels had been maintained between 3-5 ng/mL, consistent with therapeutic target range.

The patient had no relevant family history.

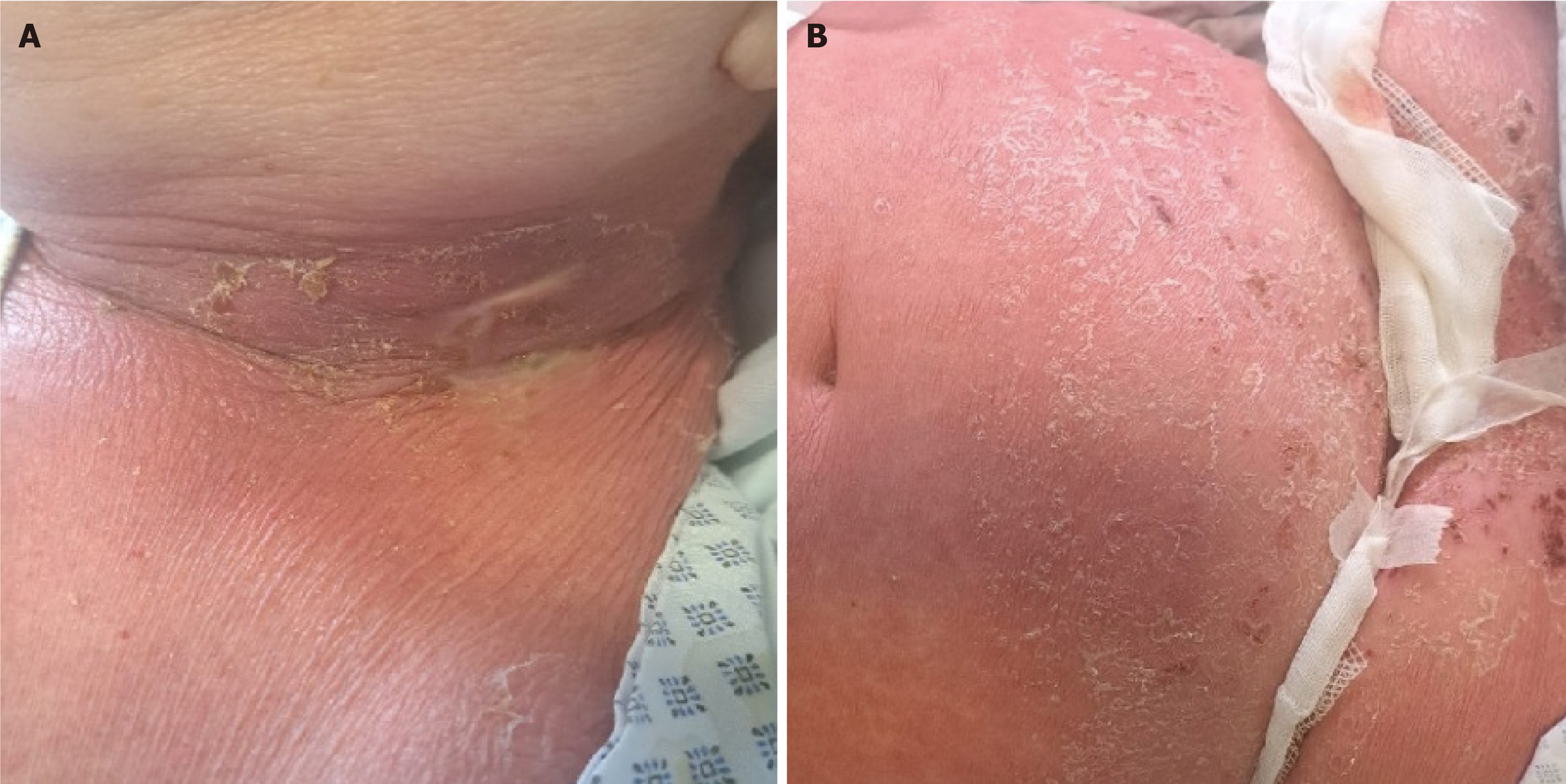

Initial clinical evaluation revealed swollen and erythematous left side of the neck with a visible purulent secretion and enlarged lymph nodes in the submental, submandibular, and nuchal regions (Figure 1A). There was also a visible maculopapular rash on the skin of the trunk, upper abdomen, back, legs, and arms, with desquamation in the flexural areas, primarily under the breasts (Figure 1B).

Initial laboratory results demonstrated leukocytosis (22.4 × 109/L), markedly elevated C-reactive protein of 327.4 mg/L, and a rise in creatinine level to 233 μmol/L, reflecting acutization of chronic kidney injury. Blood cultures and a skin swab were immediately sent to microbiology analysis, and urgent surgical incision under local anesthesia were performed, yielding 50 mL of purulent fluid, which was sent to microbiology for analysis.

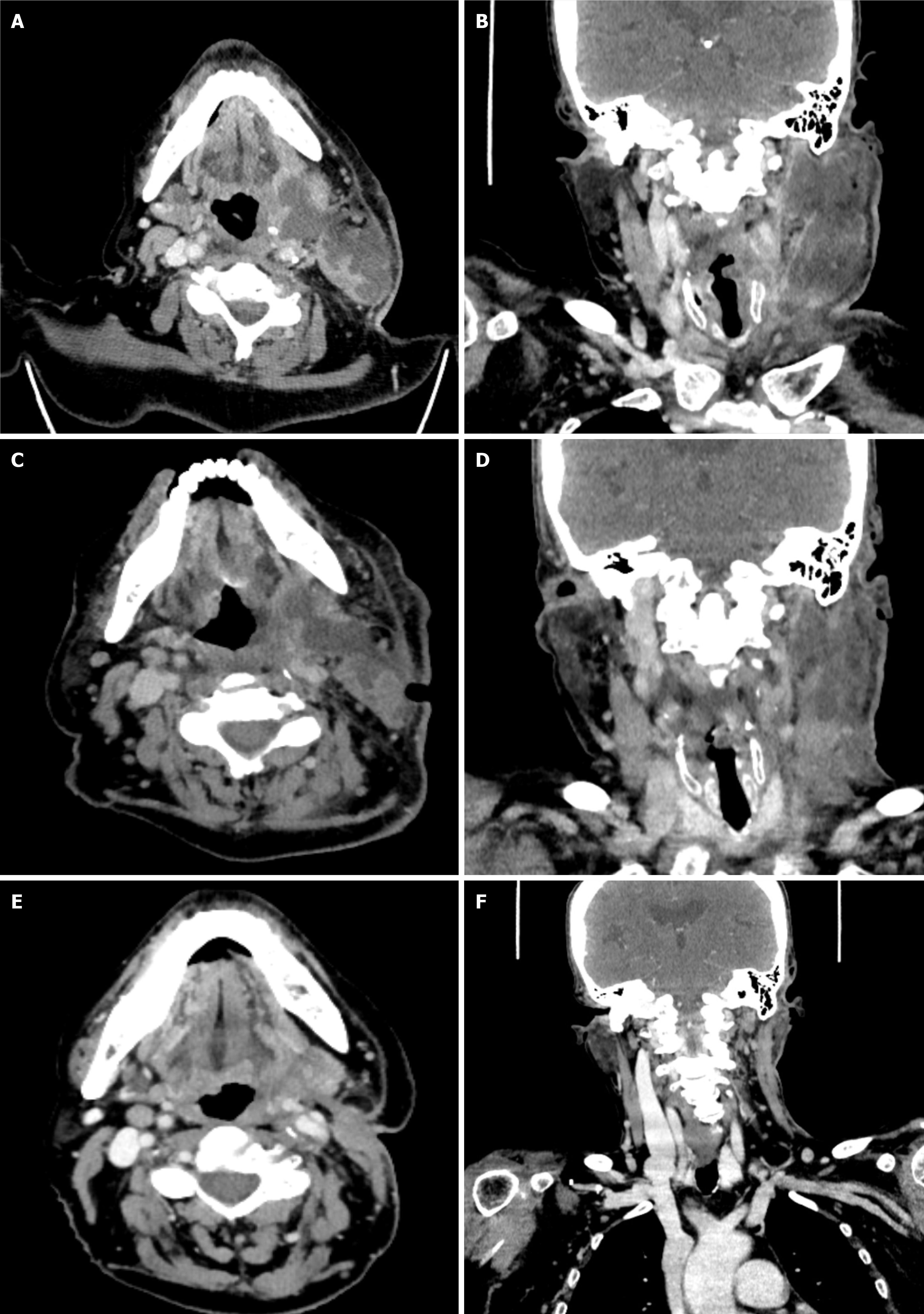

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan identified a multiloculated abscess measuring 59 mm × 32 mm with a craniocaudal extension of 85 mm, involving the left submandibular, parapharyngeal, and retropharyngeal spaces (Figure 2A and B) with evident compression of the left jugular vein and narrowing of the left pyriform recess.

Patient was discussed on Multidisciplinary Team for Liver Transplantation early during hospitalization. The team included transplant hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, intensive care specialists, surgeons, radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists. Through coordinated decision-making, the immunosuppressive regimen was carefully adjusted to balance the risk of infection and graft rejection, the antimicrobial therapy was modified according to microbiological findings and renal function and renal function was monitored.

In the following period the next day abscess and swab cultures came positive for GAS, with good sensitivity profile and without inducible resistance for clindamycin. Due to the severity of symptoms STSS was suspected.

Empirical antibiotic therapy adjusted for renal function consisted of meropenem (1 g IV every 12 hours) and vancomycin (500 mg IV every 24 hours). MMF was discontinued to mitigate the infection risk, while dosage of tacrolimus was reduced with close monitoring of drug levels. After confirming microbiological analysis on GAS from initial surgical drainage clindamycin (900 mg IV every 8 hours) was introduced into therapy and cephazolin (2 g every 8 hours) was added instead of meropenem and vancomycin. While considered, due to clinical improvement after first surgical drainage, the patients did not receive intravenous immunoglobulins at this point. Despite antibiotic therapy after initial clinical improvement, on day five of the hospitalization the patient’s condition suddenly deteriorated, with worsening neck swelling, inspiratory stridor, respiratory compromise, and evident systemic signs of STSS including fever, hypotension and more pronounced maculopapular rash. Repeated CT scan revealed persistent abscess collections with progressive retropharyngeal edema and airway narrowing, therefore a second surgical drainage under general anesthesia was performed, involving the placement of two drains for continuous purulent drainage.

Following the second surgical drainage, the patient’s condition gradually improved. Laboratory findings showed a significant reduction in inflammatory markers, with C-reactive protein decreasing to 53.0 mg/L four days after second surgical drainage. Renal function improved, with creatinine levels eventually stabilizing at 142 μmol/L. Early post-surgical follow-up CT scan of the neck revealed a partial regression of residual collection on the left side, measuring 48 mm × 11 mm (Figure 2C and D). Liver function remained satisfactory throughout hospitalization, with tacrolimus levels around 2.1 μg/L. The total duration of antimicrobial with cephazolin was five days and clindamycin for two weeks.

In the follow-up period CT scan performed one month after the second surgical drainage confirmed effective resolution, with no evidence of new abscess formation or fluid collections and scarring in the surrounding tissues (Figure 2E and F). After confirming effective abscess resolution, MMF was reintroduced at a dose of 250 mg twice daily. Patient liver function remained unremarkable after two years of follow-up and the patient completely recovered from STSS.

This case highlights the intricate balance required in managing severe infections in immunocompromised patient with invasive GAS. STSS is a severe acute-onset complication that can arise in approximately one-third of cases involving invasive GAS infections and is associated with a high mortality rate[2,3]. STSS is characterized by rapid onset of symptoms including fever, hypotension, and multi-organ dysfunction, often accompanied by a diffuse rash[7]. It occurs as a result of a complex interplay between host immunity and pathogen virulence, namely, GAS produces potent exotoxins which are able to induce unconventional activation of T cells by antigen-presenting cells resulting in simultaneous polyclonal activation of inflammatory cytokines triggering an intense immune response[8,9]. According to the study of O'Loughlin et al[10], case-fatality rates in the United States population for the period 2000 to 2004 for STSS and necrotizing fasciitis were 36% and 24%, respectively. Therefore, STSS as a life-threatening condition and requires immediate medical intervention, highlighting the critical need for early diagnosis and aggressive treatment.

In this patient STSS was precipitated by direct inoculation of GAS into a traumatic neck wound, which is according to the literature one of the risk factors in developing invasive GAS, i.e., STSS, in addition to diabetes and long-term immunosuppression[11,12]. In organ transplant recipients, immunosuppressive therapy results in decreased “net state of immunosuppression” and poses dual risk: Increased susceptibility to infections and potential complications from modifying these regimens[13]. In general, compared to patients with normal immune function, infection in transplanted patients is more difficult to recognize and treat since the signs and symptoms of infection are often diminished and infection can progress rapidly[14]. In this case, discontinuing MMF and reducing calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) reduced the burden of immunosuppression. There are no clear recommendations in adjusting immunosuppressive therapy in acute infection or sepsis and the decision is often based on clinical experience, therefore it is important to have individual and dynamic adjustment strategies of immunosuppressive therapy in response to severe infections[13].

The role of antibiotic therapy also needs to be addressed. An initial empirical broad spectrum antimicrobial therapy in septic liver transplant patients is warranted since STSS cannot be distinguished immediately from sepsis syndromes due to other pathogens. On the other hand, invasive GAS infections should be treated with narrow spectrum beta-lactam therapy with the addition of clindamycin targeting toxin production by GAS. Clindamycin is a protein synthesis inhibitor with activity during the stationary phase of bacterial growth which decreases production and expression of GAS virulence factors and exotoxins[15]. Clindamycin’s ability to suppress bacterial protein synthesis is particularly beneficial in STSS management. For example, real world data from the retrospective multicenter cohort identified 1956 inpatients with invasive β-hemolytic streptococcal infection who had been treated with β-lactam antibiotics across 118 hospitals (1079 with invasive GAS infections and 877 with invasive non-A/B streptococcal infections). In the invasive GAS group, in-hospital mortality of those who received adjunctive clindamycin was significantly lower than in those who did not (adjusted odds ratio = 0.44, 95% confidence interval: 0.23-0.81)[16]. While some recommend intravenous immunoglobulins as a part of initial STSS treatment, the data are conflicting. However, a meta-analysis from Parks et al[17] demonstrated reduced mortality in clindamycin-treated subgroup receiving intravenous immunoglobulins in pooled analysis of five studies (one randomized and four non-randomized), even though statistical significance was not reached in any of the studies in isolation.

Furthermore, advanced imaging was instrumental in guiding surgical and medical treatment. Serial CT scans provided precise localization of abscess collections and monitored therapeutic response. Timely and appropriate surgical management, including thorough debridement and drainage of necrotizing soft tissue infections or other affected areas, plays a critical role in achieving favorable outcomes. Research has indicated that inadequate or delayed initial debridement or surgery can result in a significantly higher mortality risk, therefore, to prevent the progression of the disease, surgical intervention should be initiated as promptly as possible and repeated as necessary, depending on the clinical progression of the soft tissue or related infections[18,19].

The patient’s renal dysfunction highlights another layer of complexity. Acute kidney injury in the setting of sepsis is multifactorial, involving inflammatory mediators, hemodynamic instability and nephrotoxic drugs. In this case, opti

This case report discusses a complex case of STSS following neck abscess in a liver transplant patient, exploring the clinical management strategies and the broader implications for prompt recognition and infection control in immunocompromised patients. In addition, this case underscores the importance of rapid surgical intervention, tailored antibiotic therapy, and judicious adjustment of immunosuppressive regimens. Multidisciplinary collaboration and evidence-based approaches are pivotal in managing such high-risk patients. Enhanced awareness and research are needed to improve the diagnosis and treatment of STSS in immunocompromised populations.

The authors would like to thank the Multidisciplinary Team for Liver Transplantation of the University Hospital Center Zagreb for their invaluable clinical expertise and support in the management of the patient described in this case report.

| 1. | Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:685-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1791] [Cited by in RCA: 1924] [Article Influence: 96.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Waddington CS, Snelling TL, Carapetis JR. Management of invasive group A streptococcal infections. J Infect. 2014;69:S63-S69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Stevens DL. Invasive group A streptococcus infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:2-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fishman JA. Infection in Organ Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:856-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Winston DJ, Emmanouilides C, Busuttil RW. Infections in liver transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1077-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Linder KA, Alkhouli L, Ramesh M, Alangaden GA, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Effect of underlying immune compromise on the manifestations and outcomes of group A streptococcal bacteremia. J Infect. 2017;74:450-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schmitz M, Roux X, Huttner B, Pugin J. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome in the intensive care unit. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Proft T, Fraser JD. Streptococcal Superantigens: Biological properties and potential role in disease. 2016 Feb 10. In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet]. Oklahoma City (OK): University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2016. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lappin E, Ferguson AJ. Gram-positive toxic shock syndromes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:281-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | O'Loughlin RE, Roberson A, Cieslak PR, Lynfield R, Gershman K, Craig A, Albanese BA, Farley MM, Barrett NL, Spina NL, Beall B, Harrison LH, Reingold A, Van Beneden C; Active Bacterial Core Surveillance Team. The epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcal infection and potential vaccine implications: United States, 2000-2004. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:853-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hollm-Delgado MG, Allard R, Pilon PA. Invasive group A streptococcal infections, clinical manifestations and their predictors, Montreal, 1995-2001. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Langley G, Hao Y, Pondo T, Miller L, Petit S, Thomas A, Lindegren ML, Farley MM, Dumyati G, Como-Sabetti K, Harrison LH, Baumbach J, Watt J, Van Beneden C. The Impact of Obesity and Diabetes on the Risk of Disease and Death due to Invasive Group A Streptococcus Infections in Adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:845-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Roberts MB, Fishman JA. Immunosuppressive Agents and Infectious Risk in Transplantation: Managing the "Net State of Immunosuppression". Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e1302-e1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fishman JA. Infection in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2601-2614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1386] [Cited by in RCA: 1341] [Article Influence: 74.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Andreoni F, Zürcher C, Tarnutzer A, Schilcher K, Neff A, Keller N, Marques Maggio E, Poyart C, Schuepbach RA, Zinkernagel AS. Clindamycin Affects Group A Streptococcus Virulence Factors and Improves Clinical Outcome. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:269-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Babiker A, Li X, Lai YL, Strich JR, Warner S, Sarzynski S, Dekker JP, Danner RL, Kadri SS. Effectiveness of adjunctive clindamycin in β-lactam antibiotic-treated patients with invasive β-haemolytic streptococcal infections in US hospitals: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:697-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Parks T, Wilson C, Curtis N, Norrby-Teglund A, Sriskandan S. Polyspecific Intravenous Immunoglobulin in Clindamycin-treated Patients With Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1434-1436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1454-1460. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kobayashi L, Konstantinidis A, Shackelford S, Chan LS, Talving P, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: delayed surgical treatment is associated with increased number of surgical debridements and morbidity. J Trauma. 2011;71:1400-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C, Wald R, Martensson J, Maiden M, Bagshaw SM, Glassford NJ, Lankadeva Y, Vaara ST, Schneider A. Acute kidney injury in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:816-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |