Published online Aug 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i22.105684

Revised: March 7, 2025

Accepted: April 8, 2025

Published online: August 6, 2025

Processing time: 99 Days and 21.8 Hours

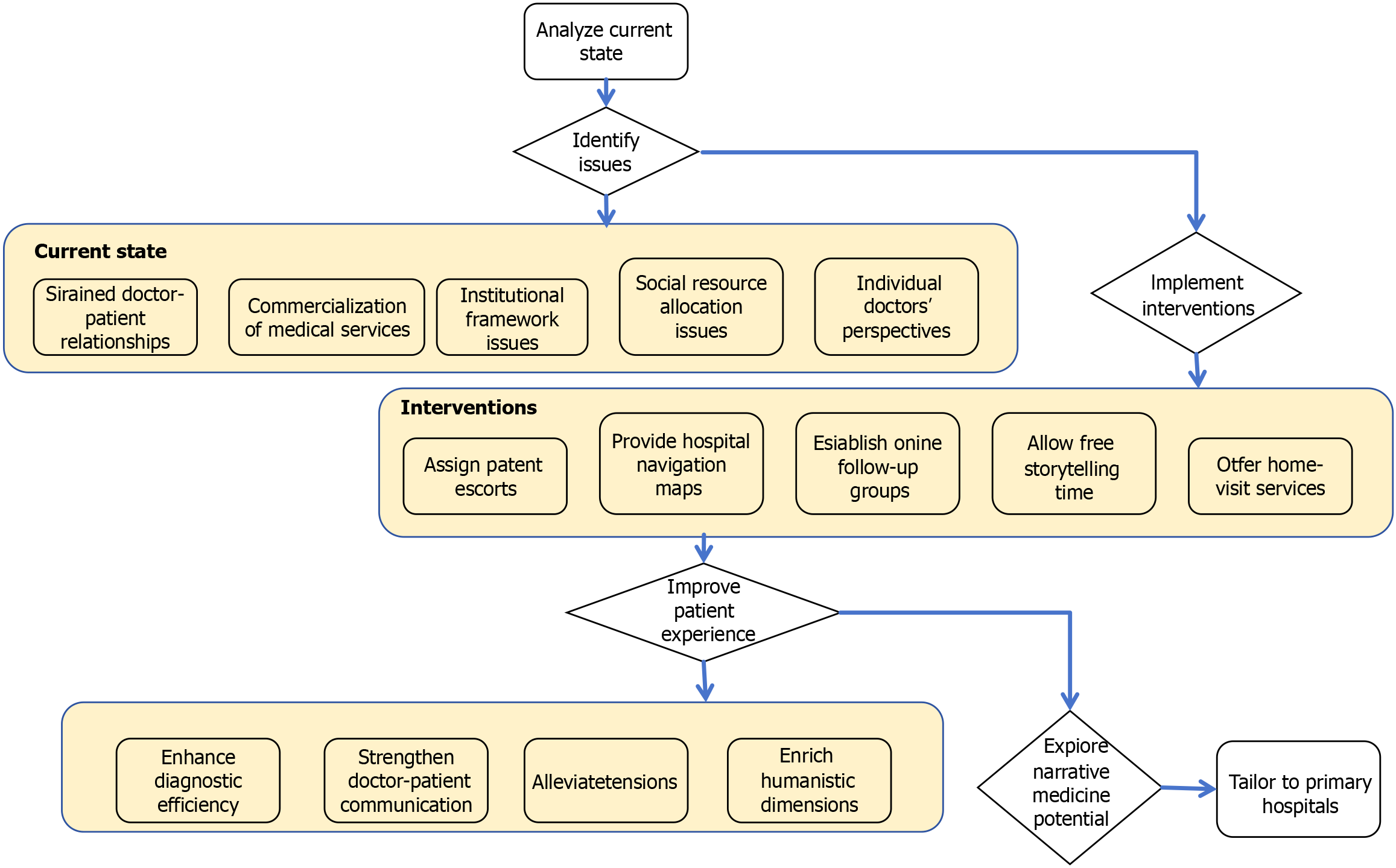

This study examines the integration of narrative medicine (NM) into primary healthcare (PHC) settings, evaluating its role in enhancing medical humanities education within grassroots healthcare institutions. Through a comprehensive literature review and case analysis, the research investigates the current state, challenges, and practical barriers to embedding NM into PHC systems, while proposing targeted strategies for improvement. The findings suggest that NM fosters stronger doctor-patient trust, enhances healthcare quality, and promotes humanistic care. However, primary hospitals face numerous challenges in advancing medical humanities, including a lack of trust between doctors and patients, tensions arising from the commercialization of healthcare, institutional limitations, unequal distribution of resources, and issues related to physicians' professional competencies and stress management. These interrelated obstacles detract from the quality of PHC services and the overall patient experience. Drawing on successful case studies from primary hospitals, the paper outlines effective strategies for overcoming these challenges. The study provides both theoretical and practical insights for advancing medical humanities in PHC, contributing to improvements in healthcare service quality and supporting the development of high standards in the healthcare sector. Ultimately, the findings aim to promote the broader adoption and ongoing refinement of NM within PHC institutions.

Core Tip: This study explores the integration of narrative medicine (NM) in primary healthcare (PHC) to enhance doctor-patient relationships, medical education, and healthcare quality. By identifying institutional barriers such as resource disparities, commercialization, and limited humanities training, the research proposes practical strategies to embed NM into PHC settings. Through case studies and policy analysis, the findings highlight how NM fosters patient-centered care, trust, and communication, ultimately improving healthcare service delivery. This study contributes to advancing medical humanities and shaping a more empathetic and effective healthcare system.

- Citation: Lei NJ, Vaishnani DK, Shaheen M, Pisheh H, Zeng J, Ying FR, Yang QQ, Wang CY, Ma J, Pan JY, Hou NJ. Embedding narrative medicine in primary healthcare: Exploration and practice from a medical humanities perspective. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(22): 105684

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i22/105684.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i22.105684

The concept of medical humanities is broad, making it difficult to define precisely. However, it can be understood as the integration of humanistic principles into the medical field, with a focus on patient care and respect. Medical humanities reflect the reverence of medicine for life and aim to cultivate healthcare professionals who balance emotional intelligence with solid professional skills.

If clinicians possess emotional intelligence but lack professional expertise, they may fail to meet patients' health needs adequately. Conversely, clinicians with excellent professional skills but limited empathy cannot effectively address the psychological needs of patients during diagnosis and treatment. Neither scenario is ideal.

Humanities in medicine emphasize a "people-oriented" approach, which contrasts with the rational, "fact- and logic-based" approach of clinical diagnosis. The integration of humanities into medicine requires healthcare professionals to nurture both empathy and logical reasoning[1]. Thus, a key issue that warrants further exploration is how to effectively incorporate humanistic education into the medical training cycle of doctors.

Since 1995, medical humanities education has increasingly intersected with professional medical education in China. Domestic institutions have begun incorporating medical humanities into medical school curricula, aligning with both national and international trends in medical education[2].

Moreover, Chinese scholars have started to compare domestic and international medical humanities education, critically assessing whether medical humanities are sufficiently reflected in China’s healthcare services. In November 2022, Wenzhou Medical University launched the Medical Humanities Education Alliance Initiative, establishing a nationwide network of medical schools focused on this area. Similarly, in November 2024, Peking University led the formation of the National Graduate Training Alliance for Medical Humanities. These initiatives highlight the growing recognition of medical humanities within China’s medical education system.

On March 17, 2009, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the Guiding Opinions on Accelerating Innovation and Development in Medical Education, proposing that "New Medical Sciences" lead medical education innovation and optimize the structure of medical disciplines. This aligns with the "Big Health" concept and reflects the needs of the new era. The integration of medical humanities into the "New Medical Sciences" reform aims to improve medical education, optimize healthcare service delivery, and cultivate medical professionals equipped with both humanistic care and innovative capabilities.

On October 25, 2016, the Healthy China 2030 Plan Outline further emphasized the integration of medical humanities with ideological and political education through a comprehensive curriculum in medical schools. This dual approach aims to nurture medical professionals with high ethical standards and exemplary medical skills.

Most recently, on September 29, 2024, the National Health Commission, in collaboration with the Ministry of Education, the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and the National Disease Control and Prevention Bureau, issued the Medical Humanities Care Enhancement Action Plan (2024-2027). This plan focuses on enhancing medical humanities education at all stages of medical training, with three main goals: Fostering humanistic literacy in medical students, promoting humanistic care within healthcare institutions, and advocating for high professional ethics.

These national policies demonstrate a gradual and systematic approach to integrating medical humanities into China's healthcare education system, evolving from structural reforms in medical education to embedding medical humanities into ideological curricula and, finally, setting concrete goals for enhancing medical humanities across various sectors.

Implementation challenges: Policy understanding and implementation deviations: Detailed analysis of differences in understanding of the national medical humanities policy among medical institutions at different levels and in different regions. For example, some primary medical institutions may simply understand the policy as holding a few humanities lectures, but fail to go deep into all aspects of medical services. This may be due to the lack of policy interpretation training and insufficient understanding of the core goals of the policy (improving the quality of humanistic care in medical services, improving doctor-patient relationships, etc.).

Inertial obstacles of the traditional medical model: Explore the obstacles to policy implementation centered on disease treatment. For a long time, medical institutions have focused on improving medical technology and disease cure rates, forming a fixed work process and evaluation system. Under this model, the introduction of medical humanities concepts such as patient-centered narrative medicine (NM) requires changing the working habits and thinking patterns of medical staff, and faces great resistance. For example, doctors may be too busy with daily diagnosis and treatment to take into account patients' narrative needs, or worry that listening to patients' narratives will affect work efficiency.

Resource constraints: Insufficient funding: Analyze the financial support provided by the state for the implementation of medical humanities policies. It points out that the shortage of funds has led to difficulties in conducting NM training, establishing relevant facilities (such as comfortable doctor-patient communication spaces), and developing and applying relevant technologies (such as NM analysis software). Taking a primary hospital as an example, due to lack of funds, it was unable to invite NM experts for training, and the narrative ability of medical staff was slowly improved.

Human resource shortage: Explain the lack of professional talents in the field of medical humanities. This includes the lack of professional NM trainers and medical staff who can effectively combine medical humanities with clinical practice. In many medical institutions, the number of medical staff who have received professional NM training is extremely low, which makes it difficult to meet the talent needs for policy implementation.

Regional differences: Differences caused by economic development level: Analyze the differences in the implementation of medical humanities policies in different economic regions. Economically developed regions may have more funds and resources invested in the construction of medical humanities, such as building advanced NM research centers and carrying out large-scale medical staff training programs. Economically underdeveloped regions may have limited resources and make slow progress in policy implementation.

The impact of cultural background differences: Explore the impact of cultural backgrounds in different regions on the acceptance and implementation of medical humanities policies. For example, in some regions and cultures, patients have a high respect for doctors and may not be used to actively sharing their stories, which requires different strategies when implementing policies such as NM. In some regions that value harmonious interpersonal relationships, policy implementation may be more likely to gain patient cooperation.

NM, an important branch of medical humanities, officially entered China in 2011, prompting extensive exploration into its integration with medical humanities[3]. Rooted in Rita Charon’s foundational "narrative competence" framework—which emphasizes attention, representation, and affiliation as core skills for clinicians[4]—NM places the patient's story at the center of medical practice. This approach aligns with the "narrative ecology" model proposed by Greenhalgh and Hurwitz[5] in 1999, which highlights the dynamic interplay of patient narratives, healthcare systems, and cultural contexts in shaping care outcomes. By emphasizing the need for healthcare professionals to understand patients' expe

Since its introduction, the Chinese government has sought to strengthen the connection between medical humanities and NM through reforms in medical models and updates to healthcare programs. For example, the rise of online medical consultation models during the COVID-19 pandemic increased patient involvement in the diagnostic process[7]. Platforms such as Good Doctor Online (Haodaifu Zaixian) and others have contributed to the emergence of an online healthcare community, subtly shifting the traditional healthcare service model and aligning with the patient-centered approach emphasized in NM[8].

This new patient-centered medical service model, which incorporates both medical treatment and emotional support, has significantly improved doctor-patient relationships and the overall quality of healthcare services. It also offers valuable insights into enhancing medical humanities in primary healthcare (PHC) institutions across China.

NM, a concept introduced by Professor Rita Charon at Columbia University, applies literary narrative theories and methods to medical practice[9]. Its core focus is on the patient's story, including the background of their illness, its impact on their life, emotional experiences, and expectations. A practice where healthcare providers listen to and incorporate patients’ personal stories into care decisions[4].

Trisha Greenhalgh In the related discussion of "NM ", the significance and value of narrative in medicine are deeply discussed. Narrative can help doctors better understand patients and improve doctor-patient communication, which is particularly important in the context of evidence-based medicine. Through listening to and interpreting patients' stories, the lack of relying solely on clinical evidence can be supplemented, and medical decisions can be more compatible with the individual situation of patients[10].

Arthur Kleinman Disease Narrative: Pain, Cure and Human Conditions (The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition) also has a profound impact. Based on years of clinical experience, he pointed out that modern medicine often treats patients as malfunctioning machines and focuses only on physiological problems. But human diseases are accompanied by complex emotions such as fear and pain. Disease is not only a biological condition, but also a human experience. The book emphasizes the interpretation of patients' disease experience as a core feature of medical treatment, which is of great significance to breaking down the barriers between doctors and patients and promoting mutual understanding[11].

This approach aligns closely with Engel’s biopsychosocial model, which emphasizes the interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors in health and illness[12]. Unlike traditional biomedical models that focus solely on physiological processes, NM bridges the gap by systematically integrating patients’ lived experiences into clinical decision-making.

NM encourages healthcare professionals to view patients not merely as carriers of disease but as individuals with unique life experiences and emotions. It also redefines disease not just as a physiological abnormality but as a deeply personal event embedded in the patient's life story. By listening to and understanding these narratives, healthcare professionals can gain deeper insights into the disease, thereby enriching medical decision-making and fostering humanistic care[6].

For example, a patient with heart disease might have developed the condition due to prolonged work stress, family conflicts, or other factors. Understanding these contextual elements is essential for identifying disease triggers, formu

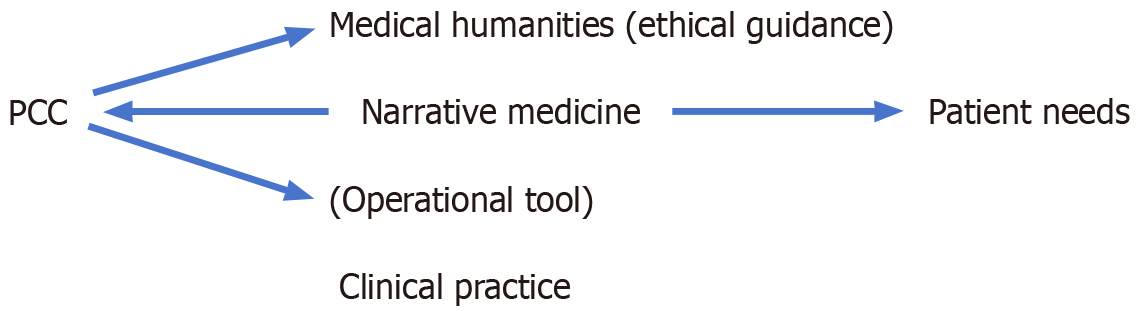

To systematically integrate medical humanities and NM, this study adopts the patient-centered care (PCC) model as the core theoretical framework. PCC emphasizes that healthcare decisions should be based on patients' unique needs, values, and preferences[13]. NM serves as the key operational tool to implement PCC in PHC through the following dimensions.

Value alignment: Medical humanities as the ethical foundation: The ethical core of PCC—respecting patient autonomy—aligns with the medical humanities principle of "reverence for life". For example, when a patient refuses treatment due to financial stress (revealed through narrative inquiry), PCC guides doctors to adjust the treatment plan

Methodological synergy: NM as the implementation pathway: PCC's six core elements (e.g., shared decision-making, emotional support) are operationalized through narrative competence[15]: Shared decision-making: Doctors use patient stories to identify preferences (e.g., "I would rather live shorter but attend my daughter's wedding"); Emotional support: Narrative listening techniques (e.g., reflective statements) validate patient experiences.

Practical outcomes: Enhancing accessibility in resource-limited settings: NM lowers communication barriers, making PCC feasible in primary hospitals. A pilot study in Yunnan Province showed that narrative-based consultations increased patients' understanding of treatment plans from 45% to 78%[16].

Theoretical model: The integrated framework can be visualized as (Figure 1).

In conclusion, the growing importance of medical humanities in China is evident, as reflected in national policies and educational initiatives. The integration of medical humanities will enhance doctor-patient relationships, improve the quality of medical services, and contribute to the high-quality development of China’s healthcare sector.

Medical education plays a pivotal role in training exceptional medical professionals for China’s public health system. As the final stage of formal education and the starting point of clinical practice, hospitals bear the responsibility of providing high-quality NM education through both clinical teaching and practice[17].

Currently, among the many challenges faced by primary hospitals in China, the strained doctor-patient relationship and the lack of medical resources stand out as particularly pressing issues. With regard to patient care, primary hospitals have often failed to emphasize the cultivation of a humanistic atmosphere within the hospital or the development of medical humanities literacy among doctors. As a result, patients' medical needs are frequently addressed without sufficient consideration of their psychological needs, and anxious patients often encounter impatient doctors and inattentive nurses[9].

This lack of humanistic care exacerbates the sense of alienation that patients experience within hospitals, further intensifying the distrust between doctors and patients and making it increasingly difficult to establish a mutually trusting and collaborative relationship. Additionally, patients often face practical challenges during their medical visits, such as confusion over which department to consult or difficulties navigating hospital layouts, which further complicate the treatment process.

The doctor-patient relationship in China is currently at a historically low point. For example, on January 20, 2020, an ophthalmologist named Tao Yong was attacked with a cleaver by a patient during a consultation at Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, affiliated with Capital Medical University. On July 13, 2024, cardiologist Li Sheng was fatally stabbed during a consultation at the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. These violent incidents underscore the deep-rooted issue of distrust between doctors and patients. Bridging the information gap between the two parties remains a challenge, making it difficult to foster trust-based relationships in the medical setting[17].

In primary hospitals, the absence of NM often leads to a focus on disease symptoms alone, without addressing the life experiences, psychological stresses, and social support factors behind the patient's condition[9]. For instance, when treating chronic disease patients, failing to consider how their illness affects family life, work, and daily functioning can make it harder for doctors to understand the reasons behind inconsistent medication adherence or emotional fluctuations. This lack of a deeper understanding exacerbates tensions between doctors and patients.

From the doctor’s perspective: Doctors may engage in self-protective behaviors that hinder their ability to fully connect with patients. To minimize medical risks, doctors may order excessive tests, adding unnecessary costs. As rare and multi-system diseases become more common, the demands on doctors' expertise grow. Newly trained clinicians, in particular, may struggle to manage complex cases, raising the risk of serious medical errors. Moreover, inconsistencies in medical ethics, combined with a lack of patience in doctor-patient communication, further prevent doctors from fully under

From the patient’s perspective: Patients' awareness of their rights has increased, leading many to seek legal recourse when encountering unsatisfactory treatment outcomes or questionable medical costs. Additionally, unrealistic expectations regarding treatment outcomes contribute to the deterioration of the doctor-patient relationship. When treatment does not lead to complete recovery or fails to meet patients' anticipated results, their distrust in doctors intensifies[20].

Moreover, patients' increasing access to online medical information can sometimes lead to skepticism about doctors' diagnoses. While patients can independently research their symptoms and form preliminary self-diagnoses, some place excessive trust in online sources, disregarding professional medical evaluations. This only deepens the cycle of distrust between doctors and patients.

The commercialization of medical services refers to the transformation of healthcare into an economic activity, driven by specific business models aimed at generating profit. This process involves both the supply and demand sides of the healthcare system, including medical institutions, doctors, patients, pharmaceutical companies, and medical device suppliers. Under this system, medical institutions are pressured to meet diagnostic and treatment performance targets, doctors are expected to fulfill department-specific goals, patients seek recovery and discharge, and medical device suppliers aim to meet sales quotas. These competing interests lead to various conflicts.

Medical institutions set performance targets, which are delegated to different hospital departments. Each department then assigns these targets to clinical teams, with doctors responsible for patient care. Patients, in turn, provide feedback on their experiences through direct communication or social media platforms. Hospitals also face scrutiny from patients, the public, and third-party oversight bodies, creating an interconnected system with multiple layers of accountability.

As the central figure in the healthcare system, patients are directly impacted by these dynamics. They are the recipients of medical treatments and the primary consumers of medical services. However, under the commercialization of medical services, patients face numerous challenges: Informal payments (red envelopes) to doctors, impatient interactions with healthcare professionals, substandard medical devices, and low-quality clinical medications. These issues contribute to increasing conflicts between patients and the healthcare system.

The lack of NM practice has led to the increasing commercialization of healthcare services, diverting the focus from a patient-centered approach. While patients expect to share their health stories and receive personalized care, the fast-paced medical environment, coupled with doctors' disengagement, often results in patients feeling like mere carriers of disease rather than individuals with emotional and psychological needs. This situation further intensifies their dissatisfaction with the commercialization of healthcare services[3].

Performance evaluation focuses on medical metrics, not NM: The current performance evaluation system in primary hospitals predominantly emphasizes medical indicators such as cure rates and patient volumes, without incorporating NM practices into the assessment framework. As a result, healthcare professionals lack the motivation to actively engage in NM, as their busy schedules leave little room for focusing on patients' personal narratives.

Furthermore, hospital training programs rarely include courses on NM, depriving medical staff of the necessary skills and methodologies for applying such practices. This structural limitation, combined with the lack of training, has significantly impeded the development of NM in primary hospitals. The Medical Humanities Care Enhancement Action Plan (2024-2027), issued by the central government, mandates a stronger focus on medical humanities within healthcare institutions, highlighting the need for systemic improvements in hospital policies and structures.

Institutional and organizational gaps in implementing NM: The lack of structured organizational development and the absence of necessary policies hinder the implementation of NM in primary hospitals. Since hospitals primarily evaluate staff performance based on medical success metrics, healthcare workers are constantly preoccupied with improving cure rates and increasing patient turnover. Consequently, they lack time to engage with patients' personal stories.

For example, a physician working in an internal medicine outpatient clinic, faced with long patient queues, may only have time to quickly inquire about symptoms and issue medical tests, with no opportunity to delve into the patient's background or personal experiences. This scenario discourages doctors from incorporating NM into their practice, marginalizing it in daily medical routines[21].

In the process of promoting the development of primary medical NM, the problems such as uneven distribution of resources, shortage of human resources and insufficient equipment have become significant obstacles and need to be solved urgently.

Shortage of human resources: Shortage of human resources is one of the key problems faced by primary medical institutions. At present, the lack of professional NM talents in basic hospitals seriously restricts the effective implementation of NM. To meet this challenge, in addition to strengthening interdisciplinary teamwork, medical students can also be attracted to participate in primary medical services by cooperating with universities to establish internship bases. Specifically, basic hospitals have signed cooperation agreements with medical schools in surrounding universities to establish a stable cooperative relationship for internship. According to the needs of basic hospitals, colleges and universities arrange medical students of different majors to practice. During the internship, medical students can not only participate in clinical diagnosis and treatment, also need to accept NM special training, assist medical staff to listen to the patient story, record key information, participate in doctor-patient communication, accumulate experience in practice, improve narrative medical ability, but also inject fresh blood for the basic-level hospital, relieve human pressure.

In addition, the development of volunteer recruitment and training plan is also an effective way to alleviate the shortage of human resources. Grassroots hospitals can recruit volunteers, such as college students, retired medical staff and public professionals. After the recruitment, a systematic training will be carried out, covering the basic knowledge of NM, communication skills, patient guidance process, etc. After the training, the trained volunteers will be organized to assist the medical staff in patient communication and guidance. Volunteers can guide patients to register and see a doctor in the outpatient hall to help them get familiar with the hospital environment; communicate with patients in the waiting area, listen to their stories and concerns, and timely feedback to medical staff, so as to reduce the work burden of medical staff and improve patients' medical experience.

Lack of equipment: Lack of equipment also restricts the development of NM in basic hospitals. In order to solve this problem, the regional medical equipment sharing platform can be used to realize the equipment sharing between primary hospitals and superior hospitals or surrounding hospitals. The local health authorities will lead the establishment of a regional medical equipment sharing platform, integrate the equipment resources of hospitals at all levels in the region, establish the equipment sharing information database, and record the equipment type, quantity, use status and other information in detail. Grassroots hospitals can query the shared equipment on the platform according to their own needs, and apply for borrowing from the equipment owned hospitals through the platform. Superior hospitals and surrounding hospitals should actively respond to the needs of basic hospitals and give priority to the use of equipment in basic hospitals in emergency. For example, when making the diagnosis of difficult cases, if the basic hospital lacks the necessary inspection equipment, it can quickly obtain the required equipment through the sharing platform and check the patients in time, so as to avoid the referral due to insufficient equipment and delay the treatment opportunity. In this way, the utilization rate of equipment can be effectively improved, relieve the pressure of insufficient equipment in primary hospitals, and provide strong hardware support for the implementation of NM in primary medicine.

Lack of humanities training for healthcare workers: Training in medical humanities and NM remains underdeveloped in primary hospitals. Existing professional training programs primarily focus on enhancing technical medical skills, such as the application of new medical technologies and advanced diagnostic methods[9]. However, medical staff often lack the essential skills needed to implement narrative practices effectively.

During routine consultations, when patients attempt to share their concerns, many doctors are unsure how to listen effectively, respond appropriately, or incorporate patients' narratives into diagnostic and treatment decisions. This gap in institutional training limits the application of NM at the primary level[22].

Poor doctor-patient communication and lack of patience: In overcrowded primary hospital outpatient departments, the limited time allocated to each patient exacerbates the communication gap. Doctors, under pressure to see a high volume of patients within tight schedules, often rush through consultations, focusing solely on symptom assessment and diagnosis, without taking the time to understand the patient’s concerns and personal health journey.

Patients frequently find themselves interrupted when attempting to explain their conditions, preventing them from fully expressing their needs. This lack of communication and empathy deepens the emotional divide between doctors and patients, making it even harder to establish trust.

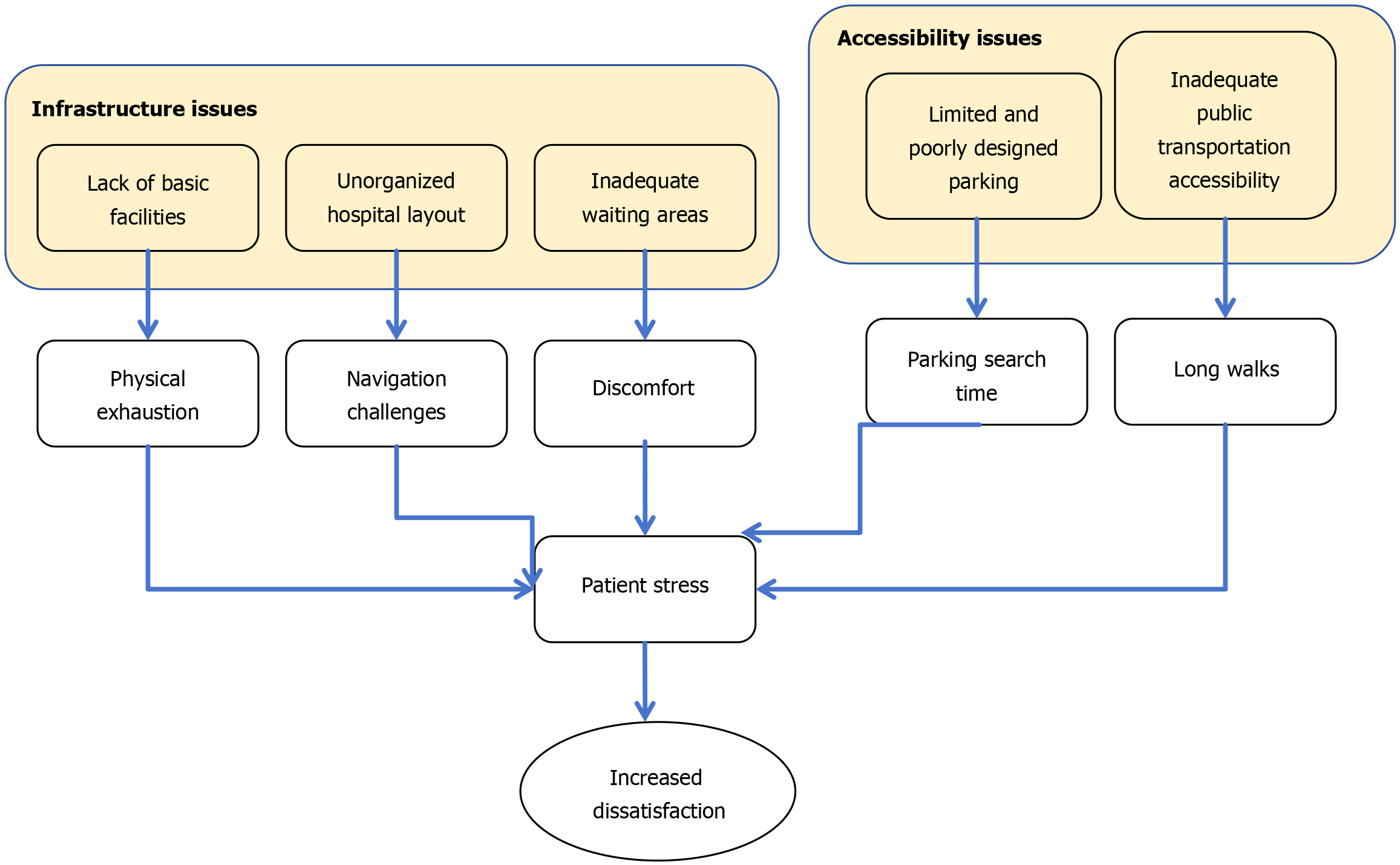

Inconvenient healthcare environment: Many primary hospitals suffer from outdated infrastructure and poor spatial organization, which further complicates the patient experience. Several factors contribute to this issue: (1) Unorganized hospital layout: Many primary hospitals are housed in older buildings with poorly planned layouts. Medical departments are often scattered across different floors or separate buildings, connected by confusing corridors and stairwells. For instance, after registration, a patient may have to navigate multiple floors and hallways to reach the appropriate clinic. This is particularly challenging for elderly or physically weak patients; (2) Inadequate waiting areas: The conditions of hospital waiting areas are often poor, with limited seating and uncomfortable hard benches that lack backrests. Patients struggle to rest adequately while waiting for consultations, leading to increased physical discomfort; (3) Lack of basic facilities: Many waiting areas lack essential amenities, such as sufficient drinking water stations. During extreme weather conditions, whether hot or cold, patients may find it difficult to stay hydrated. Additionally, poor ventilation and dim lighting create an uncomfortable atmosphere, further adding to patients’ psychological distress; (4) Limited and poorly designed parking: Hospital parking spaces are often insufficient and poorly managed. Patients who drive to the hospital may spend a long time searching for parking spots or resort to illegal parking, fearing fines while worrying about missing their appointments; and (5) Inadequate public transportation accessibility: Hospitals are often located far from major bus stops, and public transportation routes are limited, requiring patients to walk long distances to reach the hospital. This can be particularly difficult for those with severe health conditions or mobility issues, exacerbating their stress and discomfort.

These infrastructural and logistical challenges further burden patients, making their medical experiences more stressful and contributing to dissatisfaction with healthcare services (Figure 2).

The uneven distribution of public health resources in China has long been a pressing issue. Medical resources are disproportionately concentrated in economically developed regions, leaving less-developed areas with weaker healthcare infrastructure. As a result, primary hospitals in underdeveloped regions face a paradox: While they struggle with limited resources, they also experience high patient demand, further exacerbating doctor-patient tensions[23].

In more developed areas, the challenge lies in balancing diagnostic efficiency with medical humanities care, an issue arising from the unequal distribution of resources. Addressing the shortage of medical professionals and outdated equipment in less-developed areas, while breaking the cycle of limited resources and low economic returns, is crucial for improving patient experiences and strengthening humanistic care in primary hospitals.

On a societal level, there is a general lack of awareness regarding the significance of NM. When allocating resources in primary hospitals, little attention is given to the specific needs of implementing NM, such as funding for training instructors, tools for collecting and analyzing patient stories, and communication platforms. Without external support, primary hospitals struggle to independently integrate NM into their healthcare systems. This further deepens the disparity between the levels of humanistic care in primary hospitals and those in more developed medical institutions.

High workload and psychological burden: Due to the intense workload and complex medical environment, doctors often rely on rapid diagnosis and treatment methods to manage large numbers of patients within tight time constraints. This fast-paced approach makes it difficult for them to focus on actively listening to patients' personal stories. Additionally, some doctors fear that engaging deeply with patients' narratives may evoke emotional resonance, further increasing their own psychological burden. As a result, they may adopt an avoidance attitude toward NM, hindering its promotion in PHC settings[19,22].

Lack of emphasis on medical humanities development: Many doctors do not prioritize the enhancement of their medical humanities literacy. During medical education, some doctors focus excessively on acquiring technical expertise while neglecting humanistic training. Even in clinical practice, they often fail to enhance their understanding of patient psychology, doctor-patient communication, and the emotional aspects of care. This knowledge gap prevents them from providing high-quality humanistic care, further straining doctor-patient relationships.

Ultimately, the combination of high-stress work environments and a lack of emphasis on NM in medical training results in a healthcare system where doctors struggle to integrate humanistic care into their daily practices.

Enhancing medical humanities literacy in primary hospitals: The following case studies illustrate successful efforts by primary hospitals to integrate medical humanities into their practices. These examples offer valuable insights that other primary hospitals can adapt according to their specific infrastructure and resources. By implementing these strategies, hospitals can improve the quality of healthcare services and enhance humanistic care.

Case selection criteria: Disease type: Patients with chronic diseases (such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, etc.) and psychological diseases (such as depression, anxiety, etc.) were selected, because these diseases are more common in primary health care, and NM has important application value in the treatment and management of these diseases.

Age range: Patients aged 18 to 80 years old were included to ensure that the research results can reflect the characteristics and needs of patients of different age groups.

Geographical origin: Patients from urban and rural areas were included to consider the impact of medical resources and cultural backgrounds in different regions on the application of NM.

Severity of condition: There are both patients with relatively stable conditions and patients with more complex or severe conditions, so as to comprehensively evaluate the effect of NM at different stages of the condition.

Willingness to participate: Patients are required to voluntarily participate in this study and sign an informed consent form to ensure the legitimacy of the study and the authenticity of the data.

Data collection methods: Review of medical records: The research team carefully reviewed the electronic and paper medical records of the patients and collected clinical data such as the basic information of the patients (such as age, gender, occupation, etc.), disease diagnosis, treatment process, and examination results.

Interview: Face-to-face interviews were conducted with patients. The interview time was determined according to the patient's condition, generally 30 minutes to 1 hour. The interview content included the patient's disease experience, medical experience, expectations and feelings about treatment, family and social support, etc. The interview process was recorded and compiled into a written record in time after the interview.

Questionnaire survey: A special questionnaire was designed and distributed to patients for completion. The questionnaire content covers the patient's health status, lifestyle, psychological state, etc. In order to ensure the validity and reliability of the questionnaire, a pre-survey was conducted before the formal distribution, and the questionnaire was adjusted and improved based on feedback.

Data collection time point: Data collection was conducted during the patient's visit, during the treatment process, and during the follow-up period after the treatment to observe the impact of NM on patients at different stages.

Quantitative data analysis: For quantitative data obtained from medical records and questionnaires. Descriptive statistics are used to analyze the distribution of data such as patients' basic characteristics and disease-related indicators; correlation analysis is used to explore the relationship between the application of NM and patients' treatment effects (such as symptom improvement, treatment compliance, etc.).

Qualitative data analysis: For qualitative data such as interview records, thematic analysis methods are used. First, the interview records are transcribed into text word by word, and then the text is coded to group similar content into one category to form preliminary themes. Then, these themes are further analyzed and integrated to extract core themes and sub-themes. During the analysis process, the research team members had many discussions and exchanges to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the analysis results.

Primary hospitals can create a database for documenting cases in which NM has successfully improved doctor-patient relationships and treatment outcomes. These cases can serve as learning tools for internal discussions and professional development.

For example, a primary hospital developed an online case database where medical staff could upload and access case studies at any time. This allowed doctors and nurses to analyze key aspects of patient narratives—such as extracting essential information, applying communication techniques, and evaluating their impact on treatment decisions—thereby refining their narrative skills.

A notable case is the First Clinical Medical College of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, which established a parallel case database for gynecological conditions treated with traditional Chinese medicine. This initiative replaced traditional lecture-based education with a NM approach, fostering a deeper understanding of diseases and encouraging a more collaborative doctor-patient relationship. This shift aligns with the NM model of collaborative care, where both doctors and patients contribute to the treatment process[24].

A significant portion of patients in primary hospitals includes elderly individuals with chronic illnesses, migrant workers, and pregnant women. For these groups, navigating an unfamiliar hospital environment can be particularly challenging, often leading to feelings of confusion and isolation[25].

To address these challenges, hospitals can introduce intelligent navigation systems or human-guided escort services to streamline the treatment process, reduce waiting times, and improve patient satisfaction[25].

Research conducted by Sun[26] on the effects of patient escort services for diabetic patients revealed significant im

Furthermore, during the navigation process, diabetic patients received comprehensive health education that helped them: (1) Understand basic knowledge of diabetes; (2) Improve self-management of lifestyle habits; and (3) Optimize blood sugar control[27].

By implementing these intelligent navigation or escort systems, hospitals can reduce patients’ anxiety about getting lost within hospital facilities and provide meaningful humanistic care, fostering a more patient-centered healthcare experience.

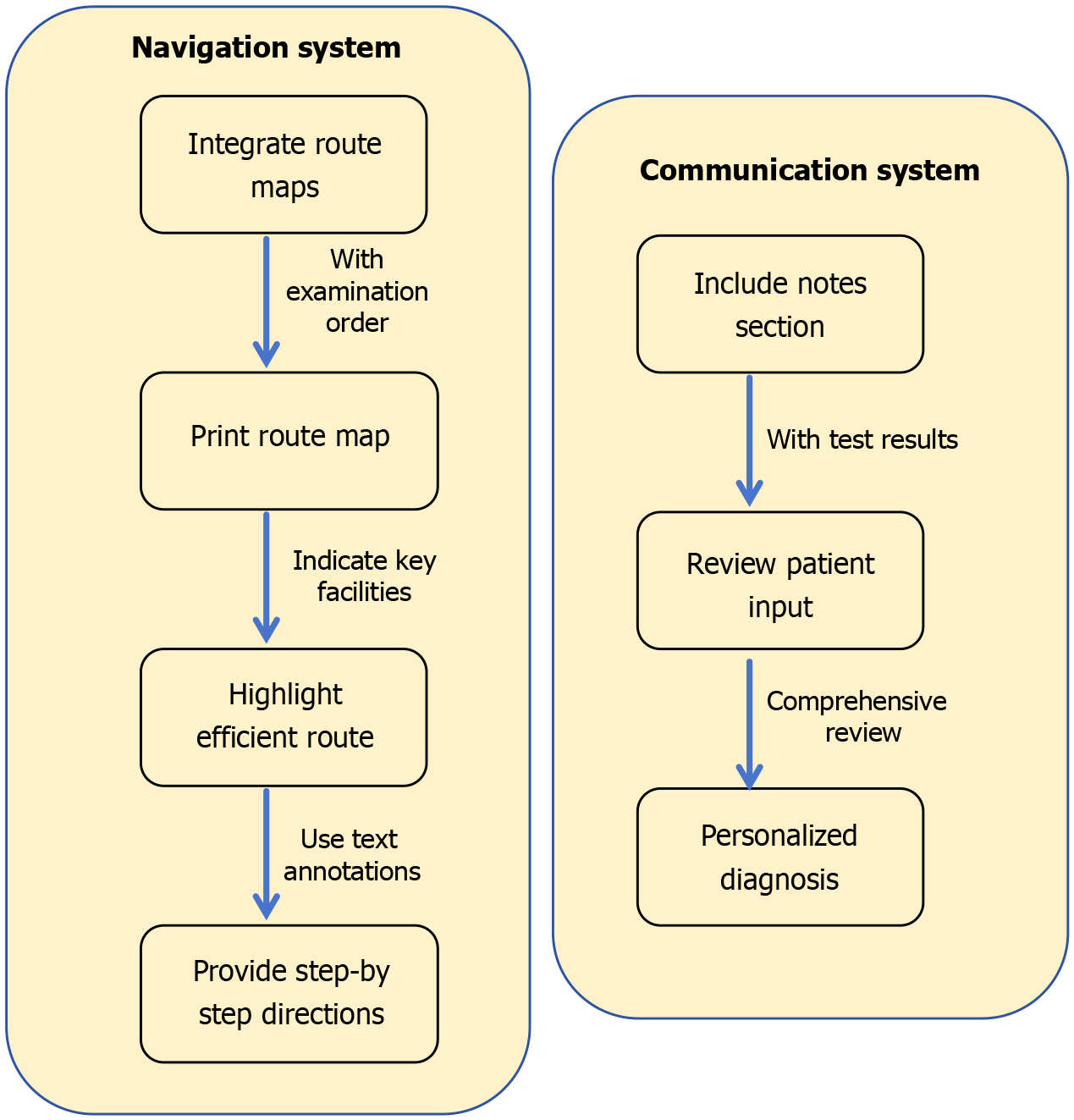

The First Affiliated Hospital of the General Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army made significant strides in improving outpatient information systems. One key innovation was the introduction of standardized examination route maps. These maps guide patients from the inpatient department to the examination department, displaying the most convenient route with color-coded arrows and prominent landmarks as navigation aids. This initiative has effectively reduced patient travel time within the hospital and minimized emotional distress caused by confusion or frustration[28].

Proposed improvements for primary hospitals: Building on this approach, primary hospitals can enhance their internal guidance systems using computerized navigation tools.

Integrating route maps with examination orders: When patients receive an examination order, a clearly labeled hospital route map can be provided alongside it.

The map should indicate building layouts, floor plans, examination areas, and key public facilities (e.g., restrooms, elevators).

Different colored lines can highlight the most efficient route from the patient's current location to the examination room.

Using simple, clear directions with text annotations: Directions should be step-by-step and easy to follow.

Example: "Exit the consultation room, turn right, walk 50 meters along the hallway, take the elevator to the second floor, and turn left to reach the Radiology Department".

Enhancing communication with patient-provided medical insights: Examination orders can include a small notes section where patients briefly describe recent symptoms, changes in their condition, and specific health concerns.

Doctors can use this information to provide a more comprehensive and personalized diagnosis.

These measures not only improve spatial orientation but also encourage active patient participation, fostering a more patient-centric and humanized hospital experience (Figure 3).

The Quzhou Hospital Affiliated with Wenzhou Medical University conducted a study on the effectiveness of an internet-based follow-up model for preterm infants after hospital discharge. They established an online follow-up group and implemented a post-discharge intervention plan, which significantly improved patient adherence and parental satisfaction[26].

In these groups, doctors provide medical advice while encouraging patients to share personal experiences in managing their diseases. They monitor preterm infants' growth, track developmental indicators, and offer timely medical support[26,29].

Many hospitals across China have adopted similar online follow-up groups for patients with chronic conditions like hypothyroidism and diabetes. Through these groups, doctors gain valuable insights into patients’ daily health behaviors and psychological states, allowing them to provide timely encouragement and guidance, ultimately enhancing patients' confidence in managing their conditions.

However, this approach adds to doctors' daily workload. To mitigate this, a designated consultation period (e.g., 7: 00 pm to 8: 00 pm) can be established to ensure that doctors respond to patient inquiries in a structured manner. Doctors can also encourage peer-to-peer interaction among patients, fostering a supportive community where individuals can exchange insights on disease management.

By adopting this model, hospitals can extend medical services into patients' daily lives and strengthen their self-management capabilities.

The "one-minute free narrative" initiative exemplifies the PCC principle of empowering patient voice. By allocating dedicated time for unstructured storytelling, doctors shift from a disease-centered to a patient-centered approach, directly addressing PCC's core requirement of "respecting patient preferences"[14].

At Rongcheng People's Hospital in Xiong'an New Area, Shanghai, doctors have introduced a "One-Minute Free Patient Narrative" initiative during outpatient consultations. This method allows patients one full minute to freely describe their condition, express their concerns, and share relevant details.

For example, a patient suffering from chronic stomach pain used this minute to detail symptoms such as pain location, intensity, and frequency, while also discussing dietary habits, work stress, and family medical history. During this process, doctors practiced active listening techniques, such as maintaining eye contact, nodding, and using affirmative body language. After the patient finished speaking, the doctor provided narrative feedback by summarizing and acknowledging the key aspects of the patient’s experience.

Example response: "I understand that your stomach pain has been affecting your work. That must be really difficult for you. Let’s work together to find the cause and help alleviate your pain".

This empathetic response helped the patient feel heard and supported, strengthening the trust and cooperation between doctor and patient.

A 25% increase in patients' willingness to actively participate in follow-up treatments.

Reduced patient anxiety, leading to improved trust in doctors.

Enhanced diagnostic accuracy, as doctors gained a more comprehensive understanding of patients' conditions.

After the implementation of this measure, patient satisfaction increased from 80% to 90% (P < 0.05), treatment compliance increased by 25%, and the doctor-patient communication time increased by 3 minutes per case. A 6-month follow-up showed that the patient's Self-Rating Anxiety Scale score decreased by 12.3% (P < 0.01)[30].

Misdiagnosis rates decreased by approximately 10%[31].

By breaking away from the rigid question-answer format, this initiative reduced patient stress, improved doctor-patient communication, and ultimately enhanced the overall quality of medical care.

After implementing the “one-minute free narrative” approach, clinical observations showed that patients were more actively involved in diagnosis and treatment decisions, and the content of the doctor-patient dialogue expanded from single symptom descriptions to life influencing factors, which indirectly improved the accuracy of diagnosis. In addition, many reviews have shown that narrative intervention can significantly improve patient experience[32].

In PHC settings, some community residents face mobility limitations that prevent them from seeking timely medical attention. To address this, family doctor teams can be contracted to provide home-based medical services to mobility-impaired patients. These teams are assigned to different neighborhoods based on residential zones and visit mobility-impaired patients during their available time slots. This initiative significantly improves access to healthcare and enhances the medical experience of local residents.

In Hongkou District, the "11253" Family Doctor Service Model was implemented, which includes: (1) 1 family doctor and 1 general practice nurse forming a team; (2) Each team contracts with approximately 2500 community residents; and (3) Three teams form one service unit, ensuring continuous healthcare services for contracted households[33].

Family doctors provide services such as: (1) Health check-ups; (2) Disease diagnosis; (3) Treatment guidance; and (4) Rehabilitation and nursing care.

During home visits, doctors dedicate specific time slots for patients and families to share how the illness affects their daily lives. This allows doctors to better understand the patient's support system and psychological needs, enabling a more holistic approach to patient care.

Medical staff training: Primary hospitals should regularly organize NM training programs. Experts in NM or experienced healthcare professionals should be invited to conduct lectures covering: (1) Theoretical foundations of NM

Example: Role-playing exercises can simulate doctor-patient interactions, allowing medical staff to practice narrative techniques in real-life scenarios. This hands-on training enhances sensitivity to patients' emotions and needs, improving PCC: (1) Role-playing training design: (a) Scenario setting: Patient role: The doctor receiving training needs to simulate a specific patient type (such as elderly patients with chronic diseases and anxious pregnant women); and Doctor role: Other participants play the role of doctors and practice the whole process of "narrative listening-empathetic response-decision-making consultation"; and (2) Key training points: (a) Non-verbal communication: Eye contact, nodding, and avoiding interruptions; (b) Language skills: Repeat and confirm: "You just said that the pain is worse at night, right?"; Emotional feedback: "It sounds like you have been under a lot of pressure recently"; and Joint decision-making: "Based on your situation, we have two options. Which one do you prefer?" (c) Real case analysis; (d) Case background: A primary hospital in Wenzhou City carried out a "role-playing-feedback improvement" cycle training for new doctors; (e) Implementation method: Phase I: Doctors watched the standardized patient simulation consultation video and analyzed the deficiencies in narrative communication; Phase II: Role-playing was carried out in groups, and senior doctors observed and scored [using the Narrative Communication Assessment Tool (NCAT) scale]; Phase III: Repeat drills after targeted improvements until the target is reached; and Results: After training, the NCAT score of doctors increased from 52.3 ± 8.1 to 78.6 ± 6.4 (P < 0.01)[34]. The patient complaint rate decreased by 41%, and outpatient satisfaction increased by 22% (internal hospital data, 2023).

Feedback mechanism: In terms of evaluation and feedback, detailed evaluation criteria were formulated, scoring from the dimensions of listening skills, language expression, emotional feedback, problem solving ability, etc. Each dimension scored 20 points, with a total score of 100 points. After each role play, professional mentors will make comments, point out the advantages and disadvantages, and provide suggestions for improvement. In the peer support section, establish a clear group operation mechanism. Determine the frequency of group activities, such as a weekly online communication and an offline discussion every month. Formulate rules for group activities, requiring members to actively share experience and help each other solve problems. The specific impact of activities on medical staff was measured by collecting regular member feedback and observing team activity.

Integrating NM into medical procedures: In outpatient consultations, physicians should allocate dedicated time at the beginning of the diagnostic process to guide patients in sharing their illness narratives. This includes detailing the onset of symptoms, prior medical experiences, and potential lifestyle factors that could contribute to the illness. For instance, when treating a patient with chronic cough, rather than focusing exclusively on symptom details, the physician could inquire about changes in the patient’s living environment, work-related stressors, or other lifestyle factors that might be influencing the condition. This approach helps identify underlying causes that might not be immediately apparent through clinical examination alone.

The implementation steps in the outpatient setting are as follows: (1) Open-ended question guidance: The doctor starts the consultation with open-ended questions (such as: "Can you tell me about the course of this illness from the beginning? Including physical feelings, life changes or worries"); (2) Active listening and recording: Use a standardized "narrative recording form" (Table 1) to record the patient's key narrative elements (symptom timeline, emotional fluctuations, social support, etc.); and (3) Narrative integrated diagnosis: The doctor combines the patient's narrative with clinical data, annotates the "narrative label" (such as "work stress related" and "lack of family support") in the electronic medical record system, and assists in formulating a personalized plan.

| Narrative element | Patient description example | Clinical relevance |

| Symptom onset | "The pain started three months ago after working overtime..." | Suggests that overwork may trigger chronic pain |

| Emotional state | "Recently, I have been having insomnia due to anxiety about my child's school admission" | Requires evaluation of the potential impact of anxiety on immune function |

| Social support | "I take care of the elderly alone, with no assistance from friends or family" | Community nursing resources should be considered |

In inpatient settings, nurses can engage patients in regular conversations during routine care to collect and document their personal narratives in medical records. This documentation enriches the clinical picture, providing healthcare providers with a more comprehensive understanding of the patient’s condition and context.

The implementation steps in the inpatient setting are as follows: (1) Daily narrative record: Nurses record patients' feedback on treatment, psychological state and life problems during morning rounds (e.g., "fatigue after chemotherapy, worry about not being able to attend my daughter's wedding"); (2) Multidisciplinary narrative discussion: The medical team analyzes the narrative content during case discussions and adjusts the treatment plan (e.g., adjust chemotherapy cycles for the above patients, coordinate social workers to assist in wedding preparations); and (3) Narrative feedback mechanism: The doctor gives patients feedback on the results of the narrative analysis at the end of the rounds (e.g., "We noticed your concerns about treatment and have adjusted plans to ensure that you can attend important events").

Furthermore, during medical team case discussions, both clinical indicators and patient narratives should be integrated. This combination can lead to the development of more personalized and holistic treatment plans, ensuring that care addresses both medical and psychosocial aspects of the patient’s health.

Creating a supportive environment and atmosphere: Primary care facilities can enhance humanistic care by showcasing patient narratives in public spaces such as waiting areas and hospital wards. This can be accomplished through storyboards or digital screens, with careful attention to safeguarding patient privacy. These displays can feature stories of successful treatments, including: (1) Personal accounts of illness experiences; (2) Challenges encountered during treat

This initiative serves a dual purpose: It provides encouragement and hope for other patients while reinforcing the institution’s commitment to PCC. Displaying these stories allows patients to feel that their experiences are not only heard but valued.

Additionally, hospitals can organize patient-sharing sessions, offering a platform for patients to exchange personal experiences and stories. Such sessions foster peer support and emotional connections, enabling patients to feel a sense of community. They also provide valuable insights to medical staff about the common needs and psychological experiences of their patient population, ultimately improving both the quality of care and the communication between patients and healthcare providers.

In addition to ongoing medical humanities training, a dedicated curriculum for NM should be established. This curriculum should encompass both theoretical foundations and practical skills to progressively enhance healthcare professionals' narrative competencies.

For instance, PHC facilities could draw on international best practices by implementing NM certification programs. These programs would encourage medical staff to actively engage with and apply NM principles and techniques, positioning NM as a central component of professional development. Such initiatives would ensure that NM becomes deeply integrated within PHC systems.

In efforts to achieve a more equitable distribution of healthcare resources, it is crucial to allocate specific resources to support the integration of NM.

The “Humanistic Care Enhancement Project” allocated 200000 yuan annually to three county-level hospitals for NM training and equipment[35]. Social donations funded AI-powered narrative analysis software, improving data collection efficiency by 40%.

Government initiatives: The government could establish dedicated funding to support the recruitment of NM specialists in primary care settings or develop remote training programs to bridge the knowledge gap between PHC providers and larger medical institutions.

Strengthening collaborations between PHC centers and more advanced medical institutions would facilitate the sharing of knowledge and the adoption of NM practices across healthcare levels.

Inter-hospital partnerships: Primary hospitals in Guangdong partnered with tertiary hospitals for remote mentorship

Government incentives: Tax breaks for hospitals achieving ≥ 80% patient satisfaction (National Health Commission, 2024 guidelines).

Encouraging social contributions: Social organizations could be encouraged to donate relevant equipment and software to help primary hospitals build platforms for collecting and analyzing patient narratives.

Such contributions would significantly improve the efficiency and quality of NM implementation at the primary level.

Advancements in digital technology can further enhance the practice and effectiveness of NM.

Developing artificial intelligence-powered NM tools: Smart voice assistants could assist doctors in recording and analyzing key elements of patient narratives in real-time. Artificial intelligence (AI)-driven speech recognition technology can automatically and accurately record patients' statements during doctor-patient communication. Compared with traditional manual recording methods, speech recognition technology greatly improves the efficiency and completeness of information collection. For example, Google's speech recognition system has an accuracy rate of more than 95% in medical scenarios, and can quickly convert patients' words into text. Doctors can check it at any time after the diagnosis and treatment, avoiding distraction from communicating with patients due to busy recording.

AI-driven systems could provide data-driven insights, offering similar case references and communication suggestions to enhance patient interactions. Based on AI's analysis results, doctors can get more targeted treatment recommendations. AI can provide doctors with personalized treatment plan references based on the patient's narration and relevant medical knowledge. For example, after the patient describes a series of symptoms and life background, the AI system can combine medical guidelines and a large number of clinical cases to recommend appropriate examination items, treatment drugs, and possible psychological intervention measures to doctors.

Integrating virtual reality and augmented reality technologies: Virtual reality (VR) technology can create an immersive environment for patients, helping them to share their experiences more relaxed and fully. For example, by creating a virtual comfortable treatment room scene, patients can tell their stories more comfortably and reduce the tension caused by the real treatment environment. In addition, VR can also be used to simulate patients' life scenes, allowing doctors to more intuitively understand the health problems patients face in their daily lives. For example, for patients with chronic pain, VR can simulate their daily activities. Patients can describe the specific situations and feelings of pain attacks in detail during the simulation process, helping doctors to better collect relevant information.

This approach would foster empathy and emotional intelligence, making NM more impactful and effective in PHC settings. When medical staff can truly understand patients' experiences, they will pay more attention to patients' individual needs and emotional states when communicating with them and formulating treatment plans, and provide more humane and practical medical services, thereby improving patients' satisfaction with medical services and treatment compliance.

Potential applications of wearable devices and mobile health technologies in NM: Wearable devices (such as smart bracelets, smart watches, etc.) and mobile health applications can collect patients' physiological data (such as heart rate, blood pressure, sleep quality, etc.) in real time, and combine the patient's symptoms, life events and other narrative information recorded through the application to provide doctors with a more comprehensive patient health profile. These data can be automatically synchronized to the medical system, and doctors can view them at any time to detect changes in the patient's health status in a timely manner. For example, when a patient records that he feels tired and has a headache that day in a mobile application, and the wearable device shows that his blood pressure is elevated, the doctor can understand the situation more promptly and intervene.

By integrating education, resource allocation, and technological innovation, NM can be successfully embedded and expanded within PHC institutions, ultimately improving PCC.

Fund application. You can use the special subsidy of the “Humanistic Care Enhancement Project” in the “Healthy China 2030” Plan to apply for NM training funds. Three county-level hospitals in Sichuan Province have been approved for an average annual training fund of 200000 yuan through this channel[34].

Linked to performance appraisal. Include “completeness of patient story records” in the “Indicators for the Evaluation of Service Quality of Primary Medical Institutions” of the National Health Commission to promote policy compliance implementation.

Optimize resource allocation: Optimize human resource allocation. Through interdisciplinary collaboration, integrate doctors, nurses, social workers and other personnel to form a small NM team. For example, when dealing with patients with chronic diseases, nurses are responsible for collecting patient narratives during daily follow-up, doctors combine these narratives to make more comprehensive judgments during diagnosis and treatment, and social workers help solve the social resource acquisition problems faced by patients. At the same time, reasonably arrange staff working hours, such as setting up special narrative communication time periods, so that medical staff have enough time to listen to patients' stories.

Optimize the allocation of material resources. Use limited space to create a warm narrative communication area, equipped with comfortable chairs, soft lighting, etc., to create a relaxing atmosphere for patients. For medical equipment, a sharing model can be adopted, and an equipment sharing mechanism can be established with superior hospitals or surrounding medical institutions. When needed, high-end equipment can be borrowed for auxiliary diagnosis to reduce the cost of purchasing own equipment.

Optimize the allocation of financial resources. Strive for special government subsidies for primary medical care, which can be used for NM -related construction, such as purchasing narrative analysis software and conducting training. At the same time, actively cooperate with charities and enterprises, strive for social donations, and establish a NM development fund.

With the help of information technology: With the help of telemedicine technology. Establish telemedicine cooperation with superior hospitals, and let experts from superior hospitals participate in the diagnosis and treatment of complex cases through video consultations and other methods. At the same time, experts from superior hospitals can provide NM guidance to medical staff in primary hospitals. For example, when doctors in primary hospitals encounter difficult diseases and it is difficult to accurately judge the condition through patient narratives, they can apply for remote consultations in time to obtain more professional advice.

Upgrade the electronic medical record system. Embed a narrative module in the electronic medical record system to facilitate medical staff to record patients' narrative information, and quickly retrieve and analyze it. Use big data and AI technology to mine patient narrative data and provide reference for clinical decision-making, such as analyzing the narratives of a large number of patients to discover potential influencing factors and comorbidity patterns of certain diseases.

Mobile medical applications. Develop mobile medical applications suitable for patients, through which patients can record their health stories, symptom changes, etc., and medical staff can view and give feedback at any time. At the same time, the application can also provide educational content related to health knowledge and NM to increase patient engagement and understanding of NM.

Layered training: Basic training: Conduct basic NM training for all medical staff, including basic concepts of NM, communication skills, listening skills, etc. Online courses and offline lectures can be combined to make use of fragmented time for learning. For example, arrange an online course once a week and organize an offline lecture once a month to allow medical staff to systematically understand the basic knowledge of NM.

Advanced training: Conduct advanced training for medical staff who have a certain foundation and interest in NM, such as narrative analysis methods and how to better combine narrative with clinical practice. Experts in the field of NM can be invited to provide guidance, and the practical ability of medical staff can be improved through case analysis, simulation exercises, etc.

Backbone training: Select some backbone medical staff to participate in advanced NM training courses or academic conferences, and train them to become NM trainers and promoters within the hospital. After these backbone personnel return, they can carry out training and sharing activities within the hospital to drive more medical staff to improve their NM level.

Diversified training methods: Case teaching: Collect successful NM cases from our hospital and other hospitals for in-depth analysis and discussion. Let medical staff learn how to apply NM to solve clinical problems through actual cases. For example, in case discussion meetings, not only analyze the patient's condition, but also share the patient's narrative and the inspiration gained from it.

Role playing: Organize medical staff to carry out role-playing activities, simulate doctor-patient scenarios, and let them practice NM skills in practice. For example, set up different patient roles and disease scenarios, let medical staff play the role of doctors and patients respectively, interact and communicate, and then review and summarize to improve their communication and coping abilities.

Peer mutual assistance: Establish peer mutual assistance groups to allow medical staff to learn and communicate with each other. Group members can regularly share their experiences and confusions in NM practice, and provide advice and support to each other. At the same time, experienced medical staff are encouraged to provide one-on-one guidance and help to novices.

The strategies outlined in this section—concept dissemination, resource integration, and technological innovation—represent actionable pathways to embed NM into PHC systems. These approaches address the multifaceted challenges identified in earlier sections, including institutional barriers, resource disparities, and professional capacity gaps. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration, leveraging digital tools, and aligning with national policy directives, primary hospitals can systematically advance medical humanities while maintaining clinical efficiency. The successful pilot programs and case studies highlighted herein demonstrate that NM is not merely an abstract concept but a practical framework capable of transforming care delivery. As these initiatives gain traction, they lay the groundwork for a more patient-centric healthcare model, one that bridges the divide between technical expertise and humanistic empathy. The following conclusion synthesizes these findings and charts a course for future implementation, emphasizing the need for sustained investment and adaptive innovation to realize NM’s full potential in primary care.

This study proposes that NM is not merely a clinical tool but a bridge connecting medical humanities' ethical ideals with the practical demands of PCC. Future policies should leverage this theoretical synergy to design training programs and evaluation systems tailored for PHC.

The Mayo Clinic in the United States abroad has achieved remarkable results in the practice of NM. The clinic has dedicated "narrative medical specialists" positions staffed by professionals with deep medical knowledge and excellent communication skills. They intervene in the whole process of patient diagnosis and treatment. During the first diagnosis, they spend a lot of time listening to patients about their own experiences, including from the life scene when the first detection of physical abnormalities, psychological changes, to various experiences in the process of seeking medical help. For example, a patient suffering from chronic pain patiently listens to how pain affects daily work, family relationships, and various tried relief methods and their effects. Afterwards, the NM specialist organized this information in detail into the patient's "narrative record" and shared with the healthcare team. Based on the "narrative medical record" and combined with the clinical examination results, the medical team developed a treatment plan more suitable for the individual needs of patients, no longer limited to simple drug treatment, but also added psychological intervention and physical rehabilitation guidance. After a period of treatment, the patient's pain is more effectively controlled, the quality of life is significantly improved, and the satisfaction with the treatment is greatly improved. During the return visit, he actively feedback his gratitude to the medical team, and is willing to actively cooperate with the follow-up treatment, and the frequency of medical treatment is more reasonable, avoiding unnecessary frequent medical treatment.

Domestic Dongguan Marina Bay Central Hospital has also made outstanding progress in the practice of NM. In May 2023, the hospital took the lead in setting up the "Life and Health Narrative Sharing Center" among the third-grade A hospitals in the city, focusing on cultivating a team of narrative medical teachers composed of 54 medical backbone. The team members went deep into various departments and led the medical staff to carry out doctor-patient narrative communication. For example, in the surgical ward, for a patient who faced complex surgery due to accidental injury, the medical staff communicated with the patient many times before surgery, listened to his injury experience, and learned the huge impact of the accident on his family's economy and psychology. Medical staff not only strive for perfection in the operation plan, but also help patients to relieve psychological pressure and solve practical difficulties through psychological counseling and contact with social assistance resources. After the operation, the patient actively cooperated with the rehabilitation treatment, and the rehabilitation process was faster than expected, and the patient and their families praised the service of the hospital. Hospital also regularly held narrative sharing, so far has been 18 games, share the experience of each department narrative medical practice, promote NM is widely used in the hospital, improve the overall medical atmosphere, improve the patient medical experience. Plan-plan, do-execution, check-check, act-processing (PDCA) is a quality management method that is also widely used in various project management and process improvements. First, in the 'planning' phase, it is necessary to define the objectives, plan and determine the plan of action; then enter the 'implementation' stage to implement the tasks as planned; then compare the deviations and problems; finally, in the 'processing' phase, analyze the problems, take measures to solve them, and standardize the successful experiences and methods in the next PDCA cycle to achieve continuous improvement. Related project case won the third national hospital medical service quality management (PDCA) case second prize and many honors.

Shunde Women and Children's Hospital of Guangdong Medical University has actively introduced the concept of NM since 2019. The hospital has compiled and printed five humanistic narrative medical books, such as "Shunde Heart Women and Children's Love", "My Family is Baymax" and so on. Through these books, medical staff will organize and share their stories with patients and patients' wishes for medical treatment. In the daily diagnosis and treatment, medical staff pay attention to the narrative communication with patients. In the pediatric clinic, in the face of children crying for fear of injections, the medical staff will first squat down, with a gentle tone to ask the children usually happy.

The findings of this study offer valuable practical examples and theoretical guidance for advancing medical humanities in PHC, presenting significant opportunities for further application and expansion.

Looking ahead, the development of a humanistic medical environment in primary hospitals must be approached as a continuous, multi-dimensional process. The integration of NM in PHC is a long-term, evolving endeavor that necessitates the collective efforts of medical institutions, healthcare professionals, the broader society, and patients themselves. By persistently implementing the strategies outlined in this study, it is possible to foster a more harmonious, compassionate, and human-centered healthcare environment in primary hospitals. Ultimately, this will lead to higher-quality, more efficient, and empathetic medical services, supporting the steady, sustainable development of PHC while safeguarding the health and well-being of the general public.

In order to measure the effect of NM in the future implementation, it is crucial to develop clear quantifiable indicators. These indicators will provide clear direction guidance for subsequent research and practice, help to evaluate the effectiveness of NM implementation, and timely adjust strategies.

Patient satisfaction: Patient satisfaction is one of the important indicators to measure the implementation effect of NM. It is planned to increase patient satisfaction by 20% over the next 5 years. Data are collected through regular patient satisfaction surveys, which cover patients 039 overall feelings of medical services, doctors communication skills, treatment effects and other aspects. A standardized satisfaction questionnaire was used to ensure the reliability and comparability of the findings. The survey was conducted every 3 months to compare the results of different stages and to analyze the changing trends of patient satisfaction.

Doctor-patient communication quality: The improvement of doctor-patient communication quality is one of the core goals of NM. The doctor-patient communication quality assessment scale was formulated to make quantitative evaluation from the dimensions of communication duration, information understanding and patients ' feelings. For example, in terms of communication duration, the outpatient communication duration is no less than 10 minutes; the information understanding is assessed by the understanding of the treatment plan and knowledge of the disease; and the emotional experience and trust. Assesses every 3 months to record changes in scores to measure improvement in the quality of physician-patient communication.

In the future development, it is necessary to be continuously promoted from multiple dimensions to realize the wide application and in-depth development of NM in primary medicine. It is believed that these quantitative indicators can objectively evaluate the effectiveness of NM in improving the quality of doctor-patient communication, and provide a basis for further optimization of communication strategies.