INTRODUCTION

Cryptococcosis is an invasive opportunistic fungal infection principally detected in specific groups of immunocompromised populations that include patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome or lymphoproliferative cancers and those managed with immunosuppression therapy[1]. Infections result from 7 different species that are derived from two Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) varieties and from five separate Cryptococcus gattii genotypes[2]. A recent national survey in China has shown cryptococcosis to have become the 3rd most common pulmonary infection nationally with an increased incidence in C. neoformans species infection and in fluconazole resistance[3]. Similar demographic changes in cryptococcal infections have been observed in Europe and North America[4] with the recent recognition of invasive and disseminated forms amongst immunocompetent patients[5] as well as an increase in incidence in this type of disease where there is no underlying immune suppression. There appear, however. to be some discrete differences in the clinical and radiological presentation between immunocompetent and immunodeficient patients[5-8]. A number of case studies of widespread cryptococcal infection have been reported in immunocompetent patients where the diagnosis was initially mistaken for metastatic lung cancer[9-13]. We report a case of disseminated cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient which mimicked a primary lung carcinoma with brain metastases, outlining the clinical, radiological and treatment response features that distinguished between the two diagnoses in this presentation.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 51-year-old male farmer presented with a history of intermittent but persistent cough accompanied by productive sputum, streaky haemoptysis and a low-grade fever (< 37.5 °C) for two weeks. He reported no chills or night sweats during this period.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms developed progressively over the two weeks preceding admission, without any other associated other systemic symptoms. He was a chronic smoker (for 30 years) with no reported prior history of tuberculosis, immune suppression, or specific risk factors for fungal or pulmonary infections.

History of past illness

The patient denied any history of significant past illnesses or prior respiratory complaints. There were no pre-existing risk factors or exposure that would suggest underlying immunosuppression. Routine immunological tests, including CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts, immunoglobulin levels, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology, were within normal limits. However, it is recognized that subtle immune dysfunctions may be present in some cases of cryptococcosis, even in individuals without overt immunosuppression. This highlights the need for a comprehensive immunological assessment in similar presentations.

Personal and family history

The patient was a farmer with no ancillary relevant personal or family medical history of note. The patient had no history of recent travel to regions endemic to Cryptococcus, such as Australia or Africa. There was no occupational or environmental exposure to known fungal reservoirs, including pigeon droppings or decaying wood.

Physical examination

On admission, the patient was afebrile, well-oxygenated and in no respiratory distress. Physical examination revealed no pulmonary abnormalities, abdominal tenderness, or lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory examinations

Initial blood tests revealed an elevated white blood cell count (11.89 × 109/L) with neutrophilia (8.26 × 109/L), anemia (hemoglobin 126 g/L), and a reduced red blood cell count (4.11 × 1012/L). Markers of inflammation, including C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were elevated (16.3 mg/L and 46 mm/hour, respectively). Tumor marker levels, including carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen 199, cytokeratin 19, alpha-fetoprotein, cancer antigen 125, and prostate-specific antigen, were within normal limits. Diagnostic tests for tuberculosis, including Ziehl-Neelsen AFB sputum staining, Lowenstein-Jensen culture and T-SPOT interferon-gamma release assays, were negative.

Serum cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) testing was positive, confirming the presence of C. neoformans capsular polysaccharide antigen. Given the pulmonary and cerebral involvement, a lumbar puncture was performed to evaluate for cryptococcal meningitis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed normal protein and glucose levels, and CSF fungal culture was negative, suggesting no active central nervous system (CNS) dissemination. Fungal cultures from sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples were performed to further characterize the infection. Sputum culture yielded C. neoformans, while BAL fluid also demonstrated fungal spores on cytological analysis. Blood cultures remained negative. These findings, in conjunction with the histopathological identification of fungal organisms in lung biopsy specimens, confirmed the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient.

Imaging examinations

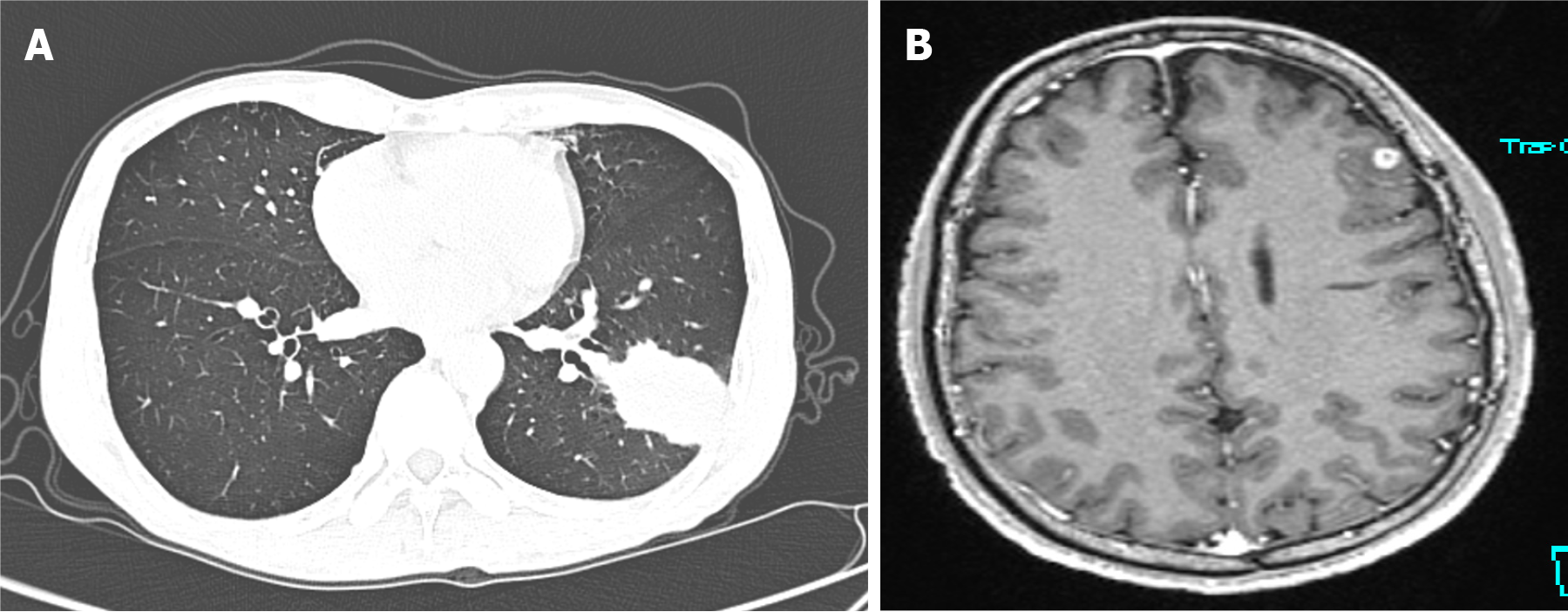

A chest computed tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a high-density mass in the posterior basal bronchopulmonary segment of the lower lobe of the left lung, characterized by a bulging margin and adjoining pleural thickening (Figure 1A). A contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (performed despite the patient being neurologically asymptomatic), revealed a ring-enhancing space-occupying lesion approximately 0.5 cm in maximal diameter in the frontal lobe (Figure 1B).

Figure 1 Imaging examinations.

A: Chest computed tomography (December 31, 2020) showing a wedge-shaped high-density lesion in the lower lobe of the left lung; B: Gd-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (December 2020) showing a small round enhancing lesion in the left frontal lobe.

Radiological findings in pulmonary cryptococcosis vary from solitary pulmonary nodules and masses to diffuse infiltrates. In this case, the lung lesion was initially suspected to be a malignant tumor due to its well-defined borders and peripheral consolidation. However, the absence of additional malignant features, such as extensive lymphadenopathy or pleural effusion, warranted further investigation. Brain MRI findings further complicated the diagnosis, as both cryptococcosis and metastatic lung cancer can present with intracranial lesions. Cryptococcal brain lesions are typically multiple, well-defined, and non-ring-enhancing in early stages, while metastatic lung cancer more commonly exhibits multiple ring-enhancing lesions with surrounding oedema. Given the initial suspicion of malignancy, a thorough histopathological and microbiological workup was necessary to differentiate between these conditions.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

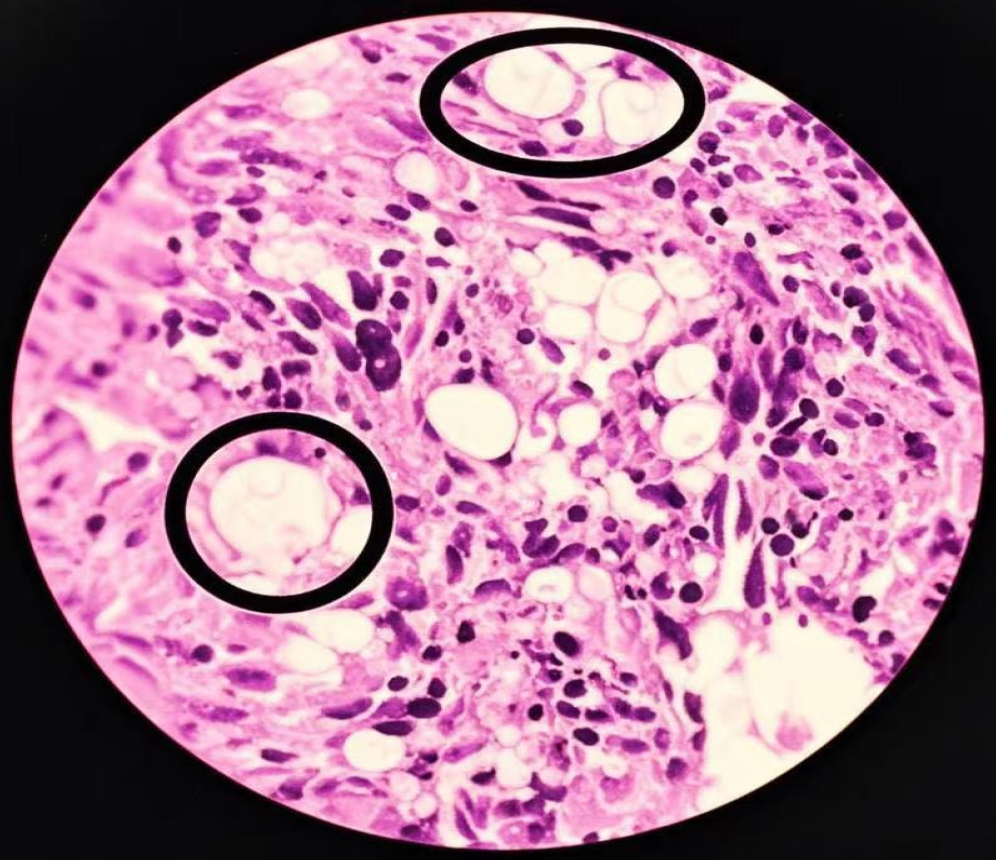

With a presumptive diagnosis of metastatic lung carcinoma, the patient was referred to the Thoracic Oncology Department for further management. A CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of the lung mass was performed without incident. Initial cytology showed a large number of fungal organisms with scattered columnar and ciliated columnar cells and macrophages. Histopathology confirmed an organizing pneumonia with extensive fungal spherules and endospores along with granuloma formation (Figure 2). Slides showed monocyte-macrophage aggregation with large numbers of pathogens which appeared as round or oval fungal organisms of variable size. Large “titan” cells up to 80 m in size were demonstrable[14] showing typical narrow-necked budding with surrounding smaller unstained pathogens which were periodic acid Schiff-positive and hexamine-silver-positive. The latter stain is an Argentaffin reaction where Ag-ion precipitates during reduction, staining the fungal cell walls black. A lumbar puncture was performed with a measured CSF pressure of 110 mmH2O but where there were no abnormalities evident either on examination or culture. Bronchoscopy and BAL were performed with no endobronchial lesion evident. Brush and lavage cytology from the left lower lung showed a large number of fungal-like organisms along with scattered columnar and ciliated columnar cells and many macrophages. transbronchial staining was negative.

Figure 2 Histopathological features of the left lung mass (hematoxylin and eosin stain; × 400).

Large “titan cell” pathogens are evident (circles) with budding of smaller pathogens surrounded by transparent halos. These are accompanied by monocyte-macrophage infiltration with fibrosis, necrosis and granuloma formation. Under low magnification, the lung tissue shows chronic inflammatory changes, and granulomatous nodules formed by the aggregation of histiocytes. Epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells are observed, accompanied by fibrous tissue hyperplasia and lymphocyte infiltration. Under high magnification, round and translucent bodies can be seen in the alveolar cavity and multinucleated giant cells. The centers of these bodies are lightly stained, with thin walls, and a clear halo can be seen around them. Combined with the results of special staining, it is consistent with cryptococcus infection.

A transbronchial biopsy was performed to characterize the lung lesion further. Histological examination revealed granulomatous inflammation with abundant mononuclear cell infiltration and large spherical fungal organisms surrounded by a mucopolysaccharide capsule, consistent with C. neoformans. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains confirmed the presence of fungal elements. In contrast, lung cancer typically demonstrates malignant epithelial cells with nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity on histopathology. The absence of these malignant features, combined with positive fungal staining, confirmed the diagnosis of cryptococcosis and effectively ruled out lung cancer. A blood CrAg test detecting C. neoformans capsular polysaccharide antigen was positive. All cytological and histopathological slides were re-evaluated with the final diagnosis made of disseminated pulmonary cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient.

TREATMENT

The patient was commenced on IV fluconazole (0.4 mg/day) for one month as an inpatient. Fluconazole treatment was continued intravenously for a further 3 weeks with improvement in the respiratory symptoms and a reduction in the amount of productive sputum along with resolution of intermittent fever. As an initial follow-up CT scan did not show any significant improvement, it was decided to add IV amphotericin B which was gradually increased from 1-40 mg and continued for a further 3 weeks period up to a cumulative dose of 308 mg. With this additional treatment the patient experienced a significant loss of appetite with maximal elevation of the blood urea (11.8 mmol/L), serum creatinine (143.3 mmol/L) and uric acid (449.0 mmol/L) necessitating temporary cessation of both anti-fungal.

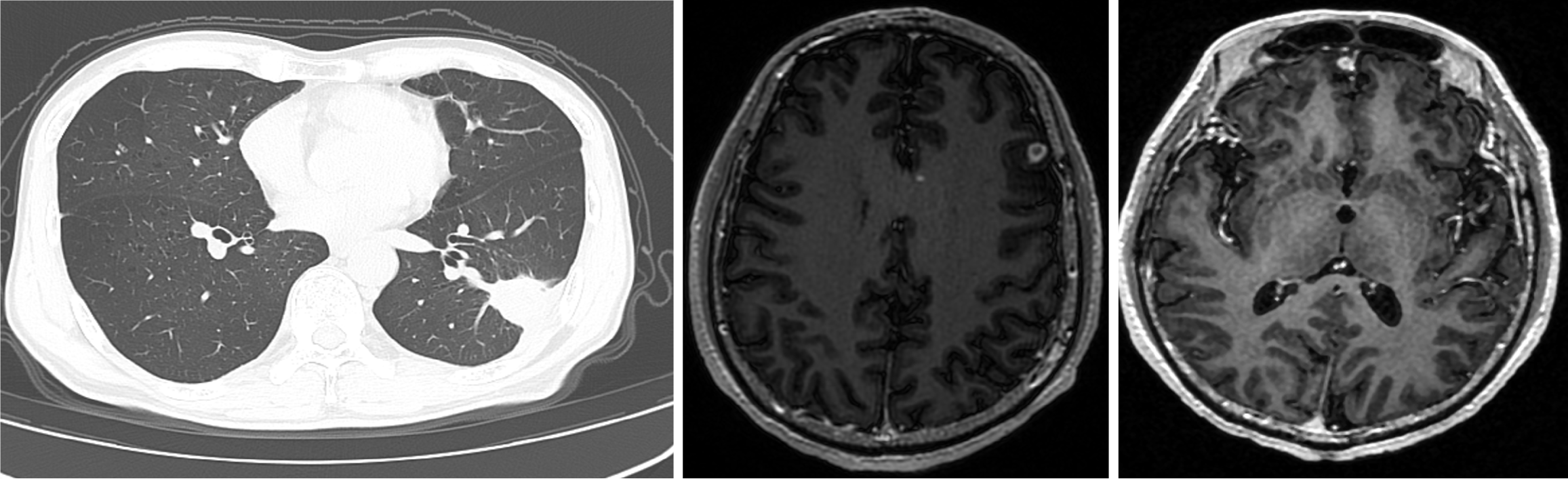

Following normalization of the renal function over one week, oral flucytosine (2 mg three times a day) was commenced and continued for a further month with a slow re-introduction of amphotericin B which was increased to 15 mg (total cumulative dose 58 mg). A follow-up chest CT showed a significant reduction in the size of the lung lesion, however, the cerebral lesions had increased in size (0.9 cm in maximal diameter) and number with persistent ring enhancement (Figure 3). Treatment was continued for a further 2 months monitoring renal function (which remained normal) with repeat MRI showing a persistence of multiple abnormal signals in both frontal lobes (the largest measuring 0.8 mm in maximal diameter) but with a slight reduction in the size of the lung mass on repeat CT scan (2.3 cm × 2.8 cm).

Figure 3 Follow-up computed tomography chest and brain magnetic resonance imaging after secondary reintroduction of flucytosine and amphotericin B.

The lung lesion showed considerable improvement however new brain lesions had formed with some increase in size of the initial cerebral mass.

As a consequence of the advancement of brain lesions despite improvement in the lung mass, the patient was readmitted to hospital and managed with combination amphotericin B (reaching a cumulative dose of 315 mg) and flucytosine therapy without incident for a further month. After a 2-week discharge the patient was readmitted for an additional month where persistence of abnormal signals was shown on brain MRI despite measured reduction in size of the primary pulmonary lesion. Amphotericin B was continued (up to a cumulative dose of 450 mg) combined with flucytosine. The total cumulative dose of amphotericin B over these admissions was 1566 mg by final discharge with a repeat chest CT after an additional month in hospital showing further reduction in the lung mass (2.2 cm × 0.9 cm). A follow-up brain MRI demonstrated resolution of the previously observed lesions. The patient was discharged from hospital on oral fluconazole (600 mg daily) and flucytosine (4 tabs three times a day) which were continued in combination for a further 6 weeks.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

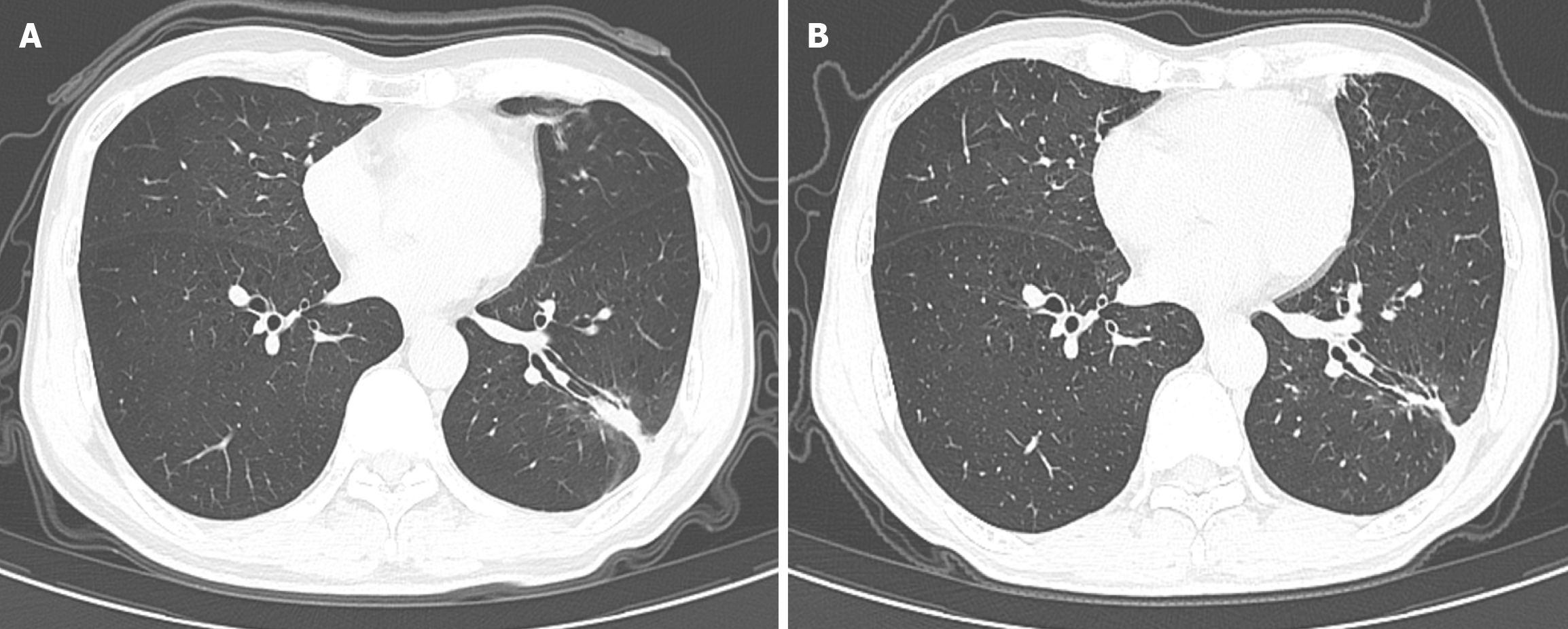

A follow-up brain MRI at 12 months demonstrated complete resolution of the cerebral lesions, while a chest CT scan revealed a residual pulmonary scar. Over two years of follow-up post-treatment, the patient remained asymptomatic, with no evidence of recurrence on imaging (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Follow-up computed tomography scans of the thorax showing near resolution of the lung mass (arrows).

A: Image was reported 12 months after initiation of antifungal therapy; B: Image a further 22 months later.

DISCUSSION

A case of disseminated cryptococcosis in an immunocompetent patient is presented that mimicked metastatic lung cancer. In most circumstances, cryptococcosis primarily presents as a pulmonary infection where it can remain latent over an extended period, only disseminating in an immunocompromised host where there is a particular propensity for fatal CNS involvement[15]. Worldwide, there are approximately 1 million cases diagnosed annually with an estimated 650000 deaths principally amongst Sub-Saharan patients with advanced HIV infection[16]. Disease is usually contracted through the inhalation of dessicated yeast spores[17]. Although cryptococcosis predominantly affects immunocompromised individuals, an increasing number of cases in immunocompetent patients have been documented. This patient presented with a pulmonary lesion mimicking metastatic lung cancer, despite lacking classical immunosuppressive risk factors. His chronic smoking history initially raised suspicion for malignancy; however, the absence of elevated tumor markers, along with positive CrAg testing, guided the diagnosis toward a fungal etiology. This case underscores the importance of considering cryptococcosis in the differential diagnosis of pulmonary masses, even in immunocompetent individuals. Disseminated cryptococcosis is, however, increasingly being recognized in immune competent patients with a greater chance in these cases that disease is confined to the lungs. It has, however, been suggested that patients with presumptively normal immunity if exposed to virulent strains or a high inoculum definitively require investigation for underlying predisposing conditions or for occult malignancy[18]. The usual radiological appearance of pulmonary disease consists of isolated or multiple nodules, although occasionally it appears as a reticulonodular pattern or as frank lobar consolidation[7]. Chest CT imaging plays a crucial role in differentiating pulmonary cryptococcosis from lung malignancy. While cryptococcosis often presents with solitary nodules or diffuse infiltrates, lung cancer typically appears as a primary mass with irregular borders, invasion of adjacent structures, or evidence of metastasis. In our case, the lung lesion had a well-demarcated appearance with no mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which, in retrospect, was more suggestive of an infectious aetiology rather than malignancy. Similarly, brain MRI can assist in distinguishing cryptococcal lesions from metastatic brain tumors. Cryptococcosis is more likely to produce multiple, well-circumscribed lesions without significant perilesional oedema in its early stages. In contrast, metastatic lung cancer often presents with multiple ring-enhancing lesions associated with significant mass effects and vasogenic oedema. The imaging findings in this case, while raising suspicion for metastasis, required further laboratory and histological confirmation for definitive diagnosis. Although there may be similarities between immune-suppressed and immune-competent cases, miliary disease, extensive lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions or cavitation are more common in cases with immunocompromise. The single nodular pattern of disease or a presentation as lobar consolidation can be difficult to differentiate from a primary lung cancer particularly when there is CT contrast enhancement or positive[18]. Fluorine-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography or positron emission tomography/CT scanning[9,19,20]. Differences in presentation may also result from exposure to Cryptococcus gattii variants which are less ubiquitous and which are more often geographically linked to tropical and subtropical climates as well as proximity to certain types of Eucalyptus trees[21]. The symptoms in our patient were non-specific in keeping with most other reports[13,15]. These included an intermittent but persistent productive cough with streaky haemoptysis and a low-grade fever. There were no specific symptoms indicating CNS involvement even when coincident brain lesions increased in size and number during the initial stages of anti-fungal therapy. Travel history to endemic regions can be a useful epidemiological clue in diagnosing cryptococcosis. However, in this case, the patient had no history of travel to regions with high Cryptococcus prevalence, suggesting a locally acquired infection. This aligns with emerging data indicating that Cryptococcus infections can occur in non-endemic regions, particularly in individuals with unrecognized immune susceptibilities. A recent systematic analysis comparing immunocompetent and immunocompromised cases diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis showed a high percentage of cases in both groups to actually have no discernable symptoms (40.8% vs 30.2%, respectively)[22]. In our case, the initial assumption that the patient had a diagnosis of lung carcinoma with cerebral metastases was not unreasonable and consistent with other similar reports[9-13,23]. It is also recognized that rare cases of synchronous pulmonary cryptococcosis and lung cancer have been reported[24,25]. In our case, confirmation of the diagnosis was made via percutaneous biopsy with concomitant immunohistochemistry. The fungus was also identified in the sputum and on BAL but not in the CSF fluid. In this regard, negative CSF cytology and culture is not uncommon[26]. CrAg testing is a critical diagnostic tool for cryptococcosis, particularly in cases with pulmonary or CNS involvement[27]. A positive serum CrAg test is highly sensitive and specific for C. neoformans, even in immunocompetent hosts. While our patient’s CSF culture was negative, the presence of CrAg in the blood and positive fungal cultures from respiratory specimens confirmed the diagnosis. This highlights the importance of incorporating antigen testing and fungal cultures into the diagnostic workflow for suspected cryptococcosis. Additionally, tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA 21-1 were within normal limits, supporting the exclusion of lung cancer as a primary diagnosis. Given that cryptococcosis can mimic malignancy radiologically, comprehensive laboratory testing, including antigen detection and fungal culture, plays a pivotal role in distinguishing between these two conditions[19]. A definitive diagnosis of cryptococcosis often requires an integrated approach combining clinical history, imaging, laboratory tests, and histopathological examination. While CSF analysis is a key component in evaluating CNS involvement[28], negative findings do not completely exclude localized cryptococcal lesions. In this case, the absence of CSF abnormalities may suggest early or localized infection rather than disseminated cryptococcal meningitis. Although this patient was immunocompetent by standard laboratory criteria, studies have shown that subtle immune dysfunctions may predispose certain individuals to cryptococcal infection. Even in the absence of HIV or overt immunosuppression, factors such as impaired macrophage function, defects in innate immunity, or environmental exposures could contribute to disease susceptibility. Future studies should consider comprehensive immunological assessments in cryptococcosis patients without apparent risk factors. Additionally, it is important to contextualize this case within the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic period. During this case, the COVID-19 in the region was largely under control. Emerging evidence suggests that severe acute respiratory distress syndrome corona virus-2 infection may have immunomodulatory effects that could predispose individuals to opportunistic infections[29]. While this patient had no documented history of COVID-19, local epidemiological trends at the time of diagnosis should be considered when evaluating potential immune interactions with fungal infections.

CONCLUSION

It has as in this case, been recommended that patients should routinely undergo a lumbar puncture (unless contraindicated) along with neuro-imaging in order to exclude underlying CNS involvement[30]. The presence of “titan” cells is a manifestation of the ability of C. neoformans to abruptly enlarge in size and to pose a barrier to immune elimination, enhancing dissemination and fungal latency[14,31]. These virulent cells are more commonly a feature of cryptococcosis in immune deficient patients where tissue biopsy tends to show minimal inflammatory response, large numbers of extracellular organisms, destructive parenchymal necrosis and granuloma formation[32].

Management decisions are dependent upon the sites of involvement and the underlying immune status of patients. In these cases an oral azole such as fluconazole (200-400 mg/day) would be recommended (where tolerated) for between 3-6 months of treatment. Amphotercin B (0.5-1.0 mg/kg/day) is utilized for a 6-10 weeks period for more severe disease manifestations. The management of CNS involvement in an otherwise healthy host has been extrapolated from the guidelines of treatment in HIV-positive cohorts and is recommended as combination therapy with amphotericin B and flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for at least 2 weeks, followed by consolidation therapy with fluconazole for a further 6-10 weeks (or up to 6 months) whilst monitoring the clinical status. Such combination therapy should usually be capable of sterilizing the CSF within 2 weeks of the commencement of treatment. This approach is in accordance with the recommendations issued in 2000 by the Cryptococcosis subcommittee of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group[33].

Given the dose-dependent efficacy of amphotericin B there is a restriction on the use of this drug up to maximum tolerated doses where dose escalation is better at preserving renal function when conducted by continuous infusion rather than via traditional short-course IV administration[34]. An alternative (which was not available at our hospital given its considerable expense), could be the use of liposomal amphotericin B which has been accompanied by less risk of nephrotoxicity[35]. There should in general be a more selective use of conventional amphotericin B in mild to moderate pulmonary disease alone and it should also be borne in mind that flucytosine should not be used alone as definitive treatment because of the risk of development of fungal resistance. In summary, C. neoformans-induced cryptococcosis is quite common in China. Pathogens are plentiful in pigeon droppings and in farms around barns and contaminated soil[36]. With more cases occurring now nationally in immunocompetent rather than in immunocompromised patients, this diagnosis should always be considered in the list of differentials of a primary lung carcinoma.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Nagamine T S-Editor: Bai Y L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang WB