Published online Jul 6, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i19.104148

Revised: February 1, 2025

Accepted: February 20, 2025

Published online: July 6, 2025

Processing time: 97 Days and 23.9 Hours

Gallbladder stones are a common occurrence, with a prevalence of approximately 10% in the Pakistani population. A rare but potentially fatal complication of gallstones is cholecystogastric fistulas. The underlying mechanism involves chronic inflammation due to cholelithiasis, causing gradual erosion and even

We present a rare case of a cholecystogastric fistula in a 40-year-old female patient, successfully managed with an open surgical approach. The patient initially presented with a 6-month history of intermittent epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting, which worsened over time. Laboratory investigations and abdo

This case highlights the importance of considering cholecystogastric fistula in patients with vague gastrointestinal symptoms and chronic cholelithiasis. The report discusses diagnostic challenges, surgical approaches, and a review of the current literature on managing such rare but serious complications of gallstones.

Core Tip: A rare and potentially fatal complication of gallstones, cholecystogastric fistulas often present with vague, non-specific symptoms and are commonly diagnosed intraoperatively. Early recognition through imaging, such as computed tomography scans showing pneumobilia and atrophied gallbladder, is crucial for proper surgical planning. The choice between open or laparoscopic surgery and a single-stage or two-stage procedure depends on factors like adhesion severity, surgeon expertise, and patient comorbidities. Early cholecystectomy is essential in preventing complications related to chronic cholecystitis.

- Citation: Ali S, Anjum A, Khalid AR, Sultan MA, Noor S, Nashwan AJ. Unexpected finding of cholecystogastric fistula in a patient undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(19): 104148

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i19/104148.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i19.104148

Gallbladder stones are a common occurrence, with a prevalence of approximately 10% in the Pakistani population[1]. A rare but potentially fatal complication of gallstones is cholecystogastric fistulas. The underlying mechanism involves chronic inflammation due to cholelithiasis, causing gradual erosion and eventually leading to fistula formation[2]. This process often involves the impaction of gallstones in Hartmann’s pouch, which may erode through the gallbladder wall and form a fistula to an adjacent organ. Most cholecystogastric fistulas are discovered unexpectedly during surgery, with a 92.1% incidence of intraoperative diagnosis due to their non-specific clinical presentation[3]. In the context of gallstones, the overall incidence of bilioenteric fistulas varies between 0.15 and 8%[3,4]. These fistulas most commonly occur between the gallbladder and the duodenum (cholecystoduodenal, 77%-90%) or the colon (cholecystocolonic, 8%-26.5%), while the cholecystogastric type is notably rare (approximately 2%)[4].

Imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) scans can be used to diagnose bilioenteric fistulas by showing suggestive symptoms like pneumobilia and an atrophied gallbladder[5]. The most commonly employed treatment approach involves surgical intervention, typically cholecystectomy and fistula repair. This can be accomplished through open or laparoscopic surgery[6-8]. The decision to perform a single-stage procedure, which includes stone removal, cholecystectomy, and fistula repair, vs a two-stage procedure, where cholecystectomy is delayed, remains a subject of debate[9]. This case report aims to present our experience with a cholecystogastric fistula and provide a comprehensive review of the current literature regarding its presentation, diagnosis, and surgical management.

A 40-year-old female presented with a 6-month history of intermittent epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and frequent belching. The symptoms were non-specific initially but later became associated with meals. Vomiting became more frequent, occurring two to three times a week, and the pain became more persistent, starting to affect her daily routine.

The patient reported a gradual onset of symptoms over the past 6 months. Initially, the epigastric pain and discomfort were intermittent and non-specific, but gradually, it became increasingly associated with meals. She also had nausea and vomiting, with the latter occurring two to three times a week on average. Additionally, she also noted a sensation of indigestion and frequent belching. These symptoms progressively worsened, leading to significant discomfort and affected her daily activities. Due to the persistence and worsening nature of the symptoms, she sought medical attention for further evaluation.

The patient did not have a history of chronic medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or liver disease. There were no previous surgeries or procedures related to the gastrointestinal system, and there was no prior history of peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, or chronic pancreatitis. On abdominal ultrasound, the patient was diagnosed with cholelithiasis.

Gallstones were documented in the patient's mother and maternal aunt in the past.

The patient appeared mildly distressed due to abdominal discomfort but was in no acute distress at rest. Vital signs were stable: Temperature 37.1 °C, blood pressure 120/75 mmHg, heart rate 88 beats per minute, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. On abdominal examination, there was no palpable mass or hepatomegaly; however, there was slight epigastric pain. Murphy’s sign was positive, indicating potential gallbladder inflammation. There was no rebound tenderness or guarding, and bowel sounds were normal with no signs of peritoneal irritation. No signs of jaundice or ascites were noted.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal total leukocyte count of 7.1 × 109/L, indicating no significant systemic inflammatory response. Liver function tests showed slightly elevated alanine aminotransferase (59 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (49 U/L) but normal alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and total bilirubin levels. Since lipase and amylase levels were normal, pancreatitis was ruled out. These findings, the patient’s clinical symptoms, and imaging results supported the diagnosis of cholelithiasis without significant active inflammation (Table 1).

| Test | Result | Normal range |

| White blood cell count/total leukocyte count | 7.1 × 109/L | 4.0-11.0 × 109/L |

| Hemoglobin | 13.7 g/dL | 12.0-16.0 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 210 × 109/L | 150-400 × 109/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 59 U/L | 7-56 U/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 49 U/L | 10-40 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 53 U/L | 30-120 U/L |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase | 61 U/L | 10-71 U/L |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 mg/dL | 0.3-1.0 mg/dL |

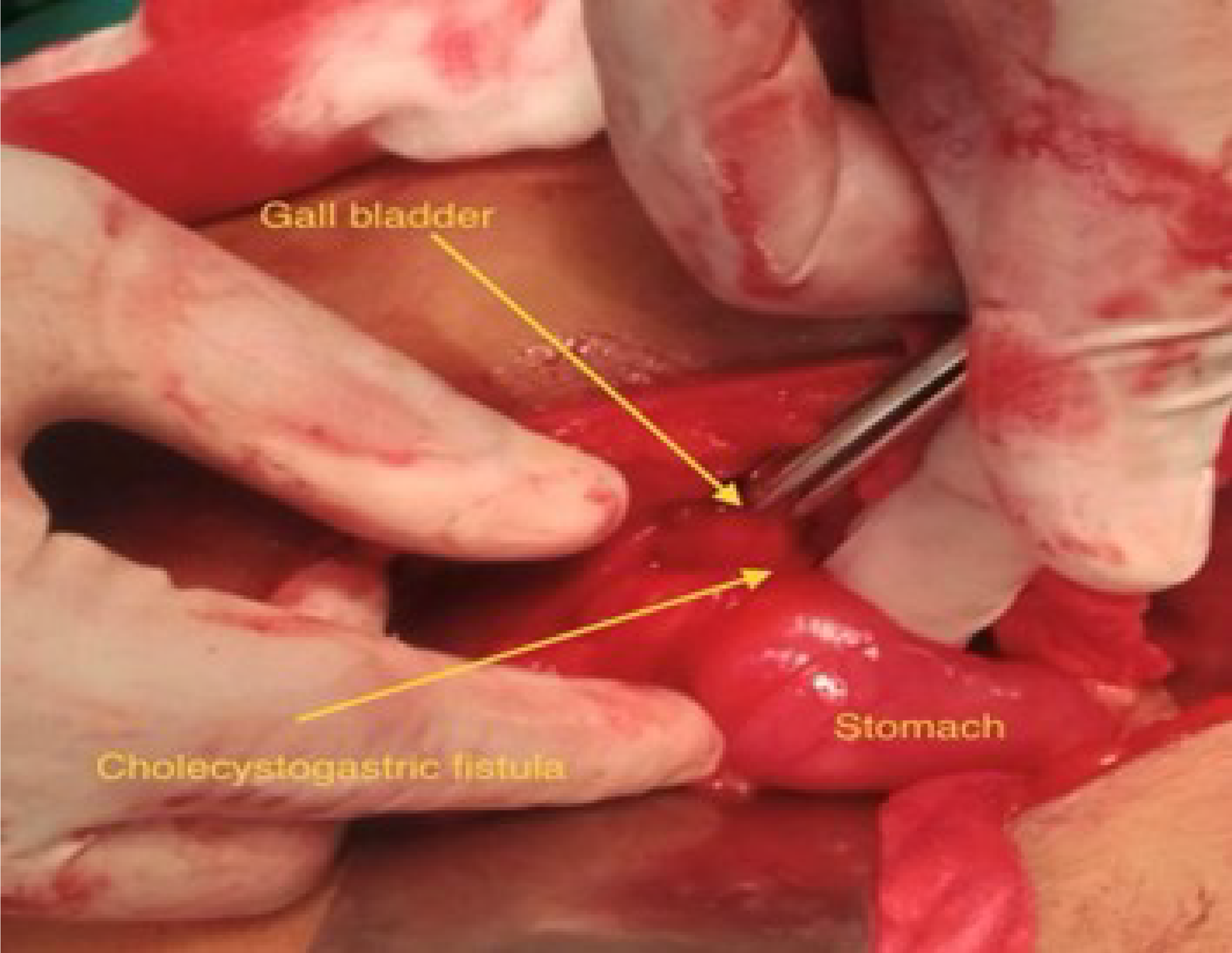

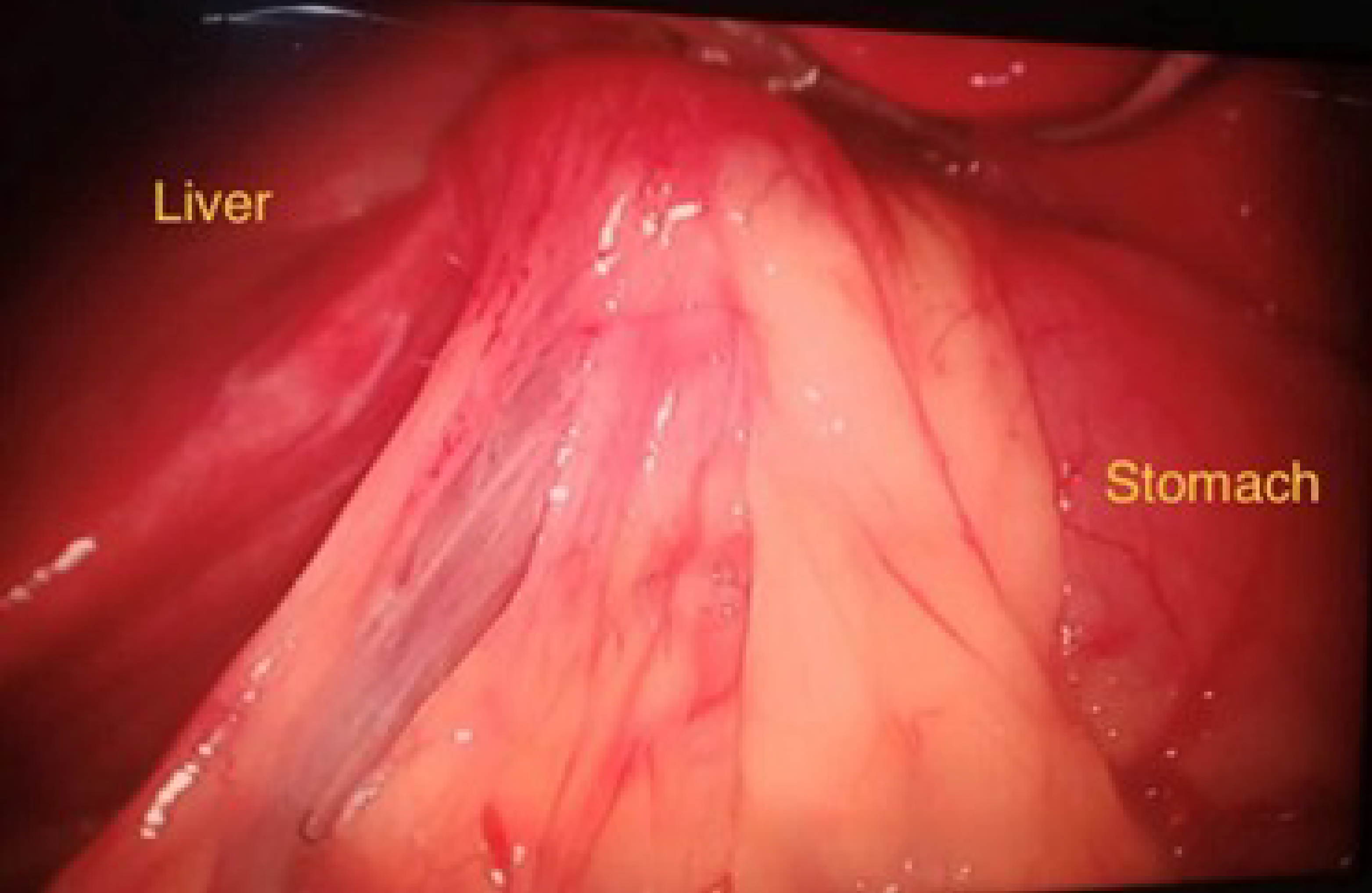

Figures 1 and 2 show the intraoperative view of the cholecystogastric fistula. The dense adhesions between the gallbladder and the stomach antrum are visible. The fistulous tract is identified during the dissection, confirming the diagnosis of cholecystogastric fistula. This image was taken before the fistula was divided, and a cholecystectomy was performed.

The patient was diagnosed with cholecystogastric fistula secondary to cholelithiasis and was confirmed intraoperatively.

The patient initially underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, during which a cholecystogastric fistula was identified intraoperatively. The laparoscopic dissection was challenging due to the presence of dense adhesions between the gallbladder, stomach, and surrounding structures, making visualization and safe separation difficult. Attempts at laparoscopic dissection revealed limited working space and significant tissue fibrosis, increasing the risk of inadvertent perforation or injury to adjacent structures. Given these intraoperative challenges, the decision was made to immediately convert to open surgery for better visualization and safer dissection. Upon opening the abdomen, extensive adhesiolysis was required to carefully separate the gallbladder from the stomach without causing additional injury. The fistula tract was found to be thickened and inflamed, necessitating meticulous dissection to avoid excessive bleeding and gastric perforation extension. Following the successful division of the fistula, antegrade dissection of the gallbladder was performed. However, friable tissue and underlying inflammation complicated the closure of the gastric defect. A double-layer suture technique using Vicryl 2.0 was applied to ensure a secure closure. The first layer provided mucosal apposition, while the second layer reinforced serosal integrity, reducing the risk of postoperative leakage.

Additionally, an omental patch was mobilized and sutured over the repair site to enhance healing and minimize tension on the closure. Careful hemostasis was maintained throughout the procedure, and saline irrigation was used to clear any residual bile and prevent contamination. A closed suction drain was placed near the repair site to monitor for any potential leakage or postoperative complications. The patient recovered uneventfully, with no signs of infection or leakage. She was discharged on the third postoperative day with a prescription for analgesics for pain management and a proton pump inhibitor to prevent gastric irritation and discomfort.

At the 10-week follow-up, the patient reported no complications or recurrence of symptoms. She was fully recovered, with no signs of infection or gastrointestinal distress. A repeat abdominal ultrasound confirmed normal findings, and her liver function tests remained normal. The patient was advised to continue with a healthy diet and lifestyle, with regular follow-up visits as needed.

Cholecystoenteric fistulas, particularly cholecystogastric fistulas, are a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of chronic cholecystitis caused by gallstones. These fistulas result from chronic inflammation leading to gradual erosion of the gallbladder wall, eventually forming a fistula with adjacent organs, such as the stomach, colon, or duodenum. The incidence of bilioenteric fistulas in patients with gallstones ranges from 0.15% to 8%, with cholecystogastric fistulas accounting for only 2% of cases[2,4]. Diagnosing cholecystogastric fistulas remains challenging due to their non-specific symptoms, which can overlap with other gastrointestinal conditions such as peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Symptoms like epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and dyspepsia may be attributed to more common conditions, leading to delays in diagnosis. In many cases, the fistula is only identified intraoperatively, as in our case, where laparoscopic surgery was converted to open surgery due to dense adhesions and unexpected intraoperative findings. Imaging modalities are crucial in detecting bilioenteric fistulas, particularly in patients with long-standing gallstone disease. Ultrasonography is often the first-line imaging modality commonly used to diagnose cholelithiasis. However, it has limited sensitivity in detecting fistulous tracts or complications such as biliary-enteric communications. CT scans, particularly with contrast, are more effective in detecting pneumobilia, atrophied gallbladder, and abnormal communication between the gallbladder and gastrointestinal structures. A CT scan may also reveal thickened gallbladder walls, which suggests chronic inflammation and fibrosis, key contributors to fistula formation[5].

In our case, the diagnosis was made intraoperatively after converting a laparoscopic procedure to open surgery due to dense adhesions. Surgical management typically involves cholecystectomy and repair of the fistula. While both laparoscopic and open surgical approaches are employed, open surgery is preferred in cases with extensive adhesions, as it provides better visualization and dissection[7]. Some studies, however, report the feasibility of laparoscopic management with minimal conversion rates[7].

A key aspect of managing cholecystogastric fistulas is choosing between a single and two-stage approach. In a single-stage surgery, the fistula is repaired, gallstones are removed, and the cholecystectomy is performed in one operation, generally preferred if the patient’s clinical condition allows[9]. The two-stage procedure, where the fistula is first add

Additionally, primary fistula repair using a double-layer closure has been proven effective. An omental patch over the repair can reinforce the closure and reduce the risk of recurrence[10]. In our case, we performed a double-layer closure with Vicryl 2.0 and reinforced it with an omental patch, which resulted in an uneventful recovery.

A study by Aguilar-Espinosa et al[11] highlighted that cholecystoenteric fistulas can lead to serious complications such as sepsis, gallstone ileus, and peritonitis, particularly in patients who are in poor general condition. The study emphasizes that prompt diagnosis and surgical intervention are crucial in reducing morbidity and preventing life-threatening complications[11].

In conclusion, cholecystoenteric fistulas should be considered in patients with a prolonged history of vague gastrointestinal symptoms, particularly in the presence of gallstones. Early diagnosis with appropriate imaging, such as CT scans, is crucial for surgical planning. The surgical approach should be tailored to the patient’s condition, with open surgery preferred in cases of extensive adhesions. However, laparoscopic repair can be an option in select cases. The decision between single-stage and two-stage surgery should be made based on the clinical condition of the patient and the extent of the fistula.

Cholecystogastric fistula, though rare, is a serious complication of chronic cholelithiasis that can present with vague, non-specific symptoms, making diagnosis challenging. In our instance, extensive adhesions led to the shift from laparoscopic to open surgery, and the fistula was discovered intraoperatively. Early diagnosis and appropriate imaging, such as CT scans, are crucial in surgical planning. The degree of adhesions, the patient's clinical state, and the surgeon's experience all influence the decision between single-stage vs two-stage surgery and laparoscopic or open surgery. Our patient was successfully repaired with a double-layer closure and omental patch, with no postoperative complications. This case emphasizes the importance of considering cholecystogastric fistula in patients with chronic cholelithiasis with prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms and the need for individualized surgical management.

| 1. | Alvi AR, Siddiqui NA, Zafar H. Risk factors of gallbladder cancer in Karachi-a case-control study. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 2. | Hollins AW, Levinson H. Report of novel application of T-line hernia mesh in ventral hernia repair. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;92:106834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 3. | Gupta V, Abhinav A, Vuthaluru S, Kalra S, Bhalla A, Rao AK, Goyal MK, Vuthaluru AR. The Multifaceted Impact of Gallstones: Understanding Complications and Management Strategies. Cureus. 2024;16:e62500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pandit K, Khanal S, Bhatta S, Trotter AB. Anorectal tuberculosis as a chronic rectal mass mimicking rectal prolapse in a child-a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2018;36:264-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Faisal M, Fathy H, Abu-Elela STB, Shams ME. Prediction of resectability and surgical outcomes of periampullary tumors. Clin Surg 2018; 3: 1969. |

| 6. | Ansari ST, Bedi KS, Sahu SK. Intraoperative scoring system for grading severity of cholecystitis at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int Surg J. 2021;9:75. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Leung E, Kumar P. Bilo-enteric fistula (BEF) at laparoscopic cholecystectomy: review of ten year's experience. Surgeon. 2010;8:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prakash K, Jacob G, Lekha V, Venugopal A, Venugopal B, Ramesh H. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:180-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aamery A, Pujji O, Mirza M. Operative management of cholecystogastric fistula: case report and literature review. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;2019:rjz345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dietz UA, Wichelmann C, Wunder C, Kauczok J, Spor L, Strauß A, Wildenauer R, Jurowich C, Germer CT. Early repair of open abdomen with a tailored two-component mesh and conditioning vacuum packing: a safe alternative to the planned giant ventral hernia. Hernia. 2012;16:451-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aguilar-espinosa F, Maza-sánchez R, Vargas-solís F, Guerrero-martínez G, Medina-reyes J, Flores-quiroz P. Cholecystoduodenal fistula, an infrequent complication of cholelithiasis: Our experience in its surgical management. Revista de Gastroenterología de México (English Edition). 2017;82:287-295. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |