Published online Jun 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.103438

Revised: January 16, 2025

Accepted: February 12, 2025

Published online: June 26, 2025

Processing time: 100 Days and 5.3 Hours

Rectal foreign bodies, though uncommon, present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, particularly when they result from accidental ingestion. The non

A 48-year-old male with a history of hypertension presented with a one-year history of post-defecation anorectal pain and mild post-defecation rectorrhagia. Initial evaluation revealed hemodynamic stability and a tender, non-mucosal lesion in the anterior left rectal region. Imaging studies, including colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and endosonography, identified an erythematous, exophytic lesion and a perirectal abscess containing a foreign body. Surgical inter

This case underscores the diagnostic challenges posed by rectal foreign bodies with nonspecific symptoms and no clear history of ingestion.

Core Tip: This case report highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of rectal foreign bodies, emphasizing the crucial role of advanced imaging techniques, including colonoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and endosonography, in accurate diagnosis. A multidisciplinary approach combining endoscopic and surgical expertise is essential for successful management. Comprehensive physical examination and regular postoperative follow-up are vital to ensure recovery and monitor for complications. Patient education on the risks of ingesting foreign objects, particularly in high-risk groups, is imperative for prevention. This report underscores the importance of a thorough and methodical approach in managing rectal foreign bodies with nonspecific symptoms and no clear history of ingestion.

- Citation: Martínez-Hincapie CI, González-Arroyave D, Ardila CM. Rectal abscess secondary to foreign body insertion: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(18): 103438

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i18/103438.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.103438

Rectal foreign bodies are infrequent when they occur accidentally secondary to ingestion[1-3]. Most foreign bodies in the rectum are inserted through the anal canal because of sexual practices; however, a small proportion of these foreign bodies are due to the ingestion of foreign objects, most commonly animal bones[4-6]. Approximately 10% to 20% of foreign bodies fail to be eliminated from the gastrointestinal tract. When these advance through the digestive tract, it has been described that they can potentially lodge in the pylorus, the ileocecal valve, and the rectum, with less than 1% resulting in perforation[7-9].

A growing body of literature highlights the increasing prevalence of rectal foreign bodies, with cases ranging from accidental ingestion to intentional insertion. A U.S.-based study estimated 38948 emergency visits for rectal foreign bodies from 2012 to 2021, with an annual incidence rising from 1.2 to 1.9 per 100000 people[10]. Most cases are associated with sexual practices involving foreign objects, while a smaller percentage result from accidental ingestion[11,12]. In our case, detailed history-taking after pathology findings revealed that the foreign body—a chicken bone—was accidentally ingested during a meal. This highlights the diagnostic challenge posed by accidental ingestion, especially when patients fail to recall relevant historical events.

Complications of rectal foreign bodies include anal incontinence, perforation, fistulas, and the formation of perirectal abscesses. The symptoms presented by patients are very nonspecific and have a wide spectrum, ranging from mild lower abdominal pain, constipation, rectal pain, and pelvic pain to rectal bleeding with signs of perforation in complicated cases[2]. The presentation of patients with accidental unconscious ingestion can be a true diagnostic challenge as these patients may not recall any historical trigger for their symptoms, making an accurate diagnosis a real challenge. We present the case of an adult patient who accidentally ingested bone material, which led to a significant inflammatory process with the formation of a secondary perirectal abscess.

A 48-year-old patient with a history of hypertension consulted the coloproctology service due to a one-year history of post-defecation anorectal pain, associated with mild post-defecation rectorrhagia.

The patient denied weight loss, alterations in bowel habits, or stool consistency.

Notably, within the patient's medical history, only the presence of arterial hypertension was mentioned. However, retrospectively, it was identified that more than a year ago, the patient had suffered a choking episode due to accidentally ingesting a chicken bone. At that time, the patient did not mention this incident, as he did not believe it had any relation to his current clinical picture.

Arterial hypertension.

During the initial evaluation, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. On physical examination, the patient was alert, oriented in all three mental spheres, with a soft abdomen, no tenderness on palpation, and no masses or hepatomegaly. A digital rectal examination revealed no anal fissures or polyps. However, a non-mucosal lesion was palpated in the anterior left region above the left puborectalis muscle, which was tender to touch but without active bleeding. Based on these findings, imaging studies were requested for a more objective characterization of the lesion.

Biopsies reported granulation tissue.

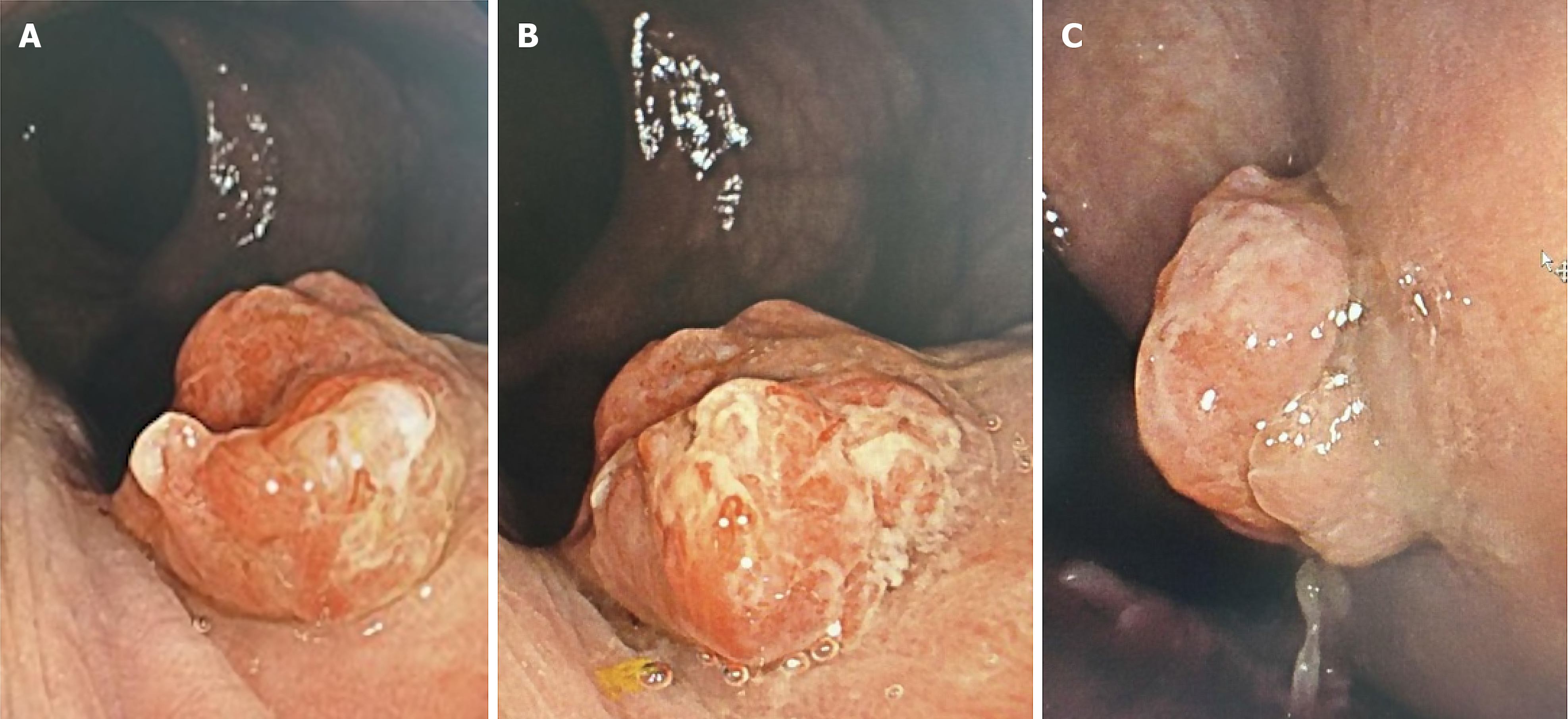

Various imaging studies were utilized to comprehensively address the patient's clinical picture. A colonoscopy was performed as an initial study. Given the patient’s age (48 years) and his chronic symptoms of one year, which included post-defecatory anorectal pain and mild rectal bleeding, and since he had not undergone prior screening studies for colorectal cancer, this was deemed necessary. The colonoscopy revealed an erythematous, exophytic lesion in the distal rectum, proximal to the dentate line, measuring 13 mm × 10 mm with an inflammatory, lobulated, villous appearance, involving less than 20% of the circumference and not causing rectal lumen stenosis (Figure 1).

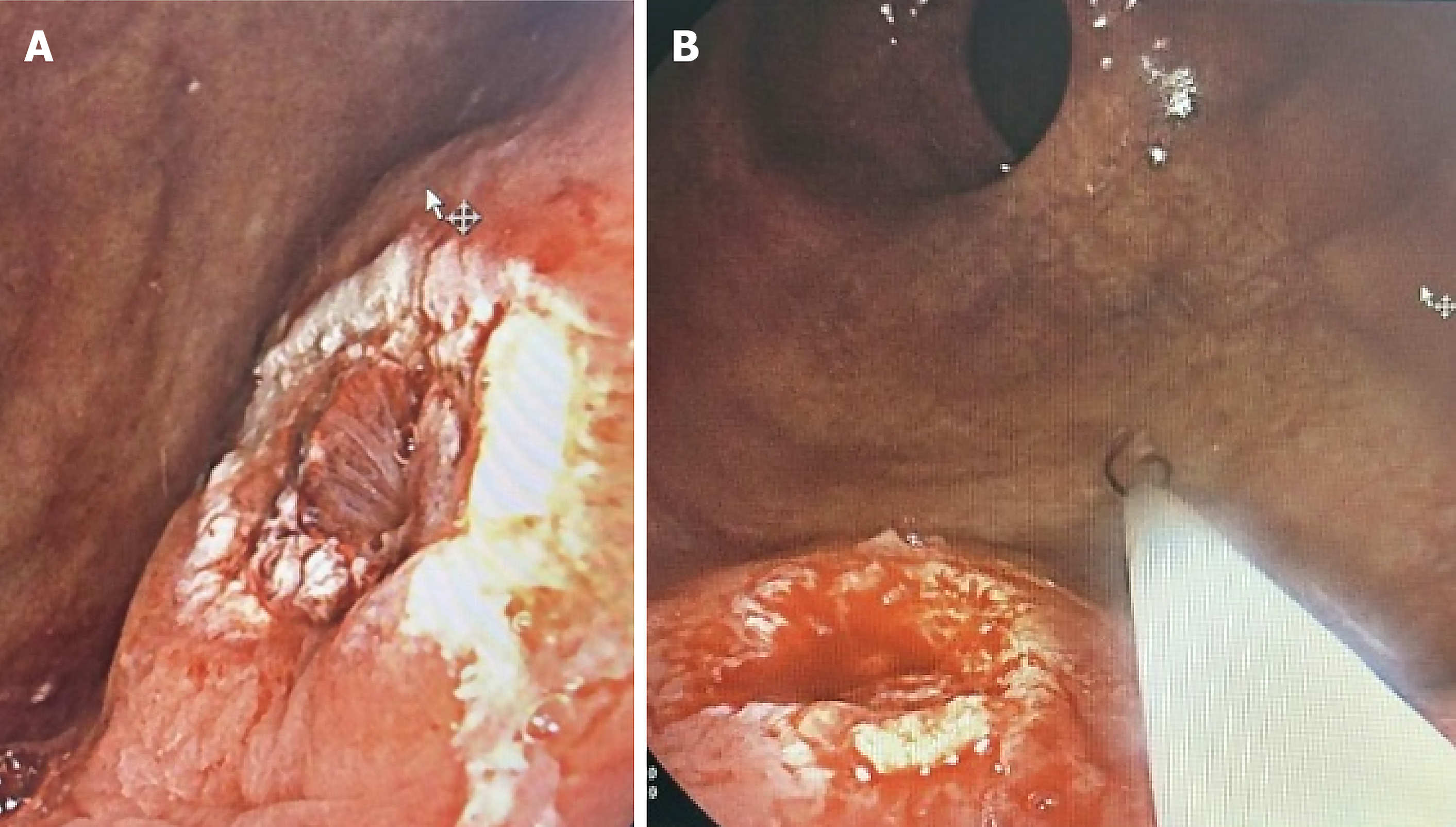

Following this study, an endoscopic polypectomy was successfully performed using a hot snare technique, leaving the bed without bleeding (Figure 2). Samples were sent to pathology, which reported a hyperplastic polyp.

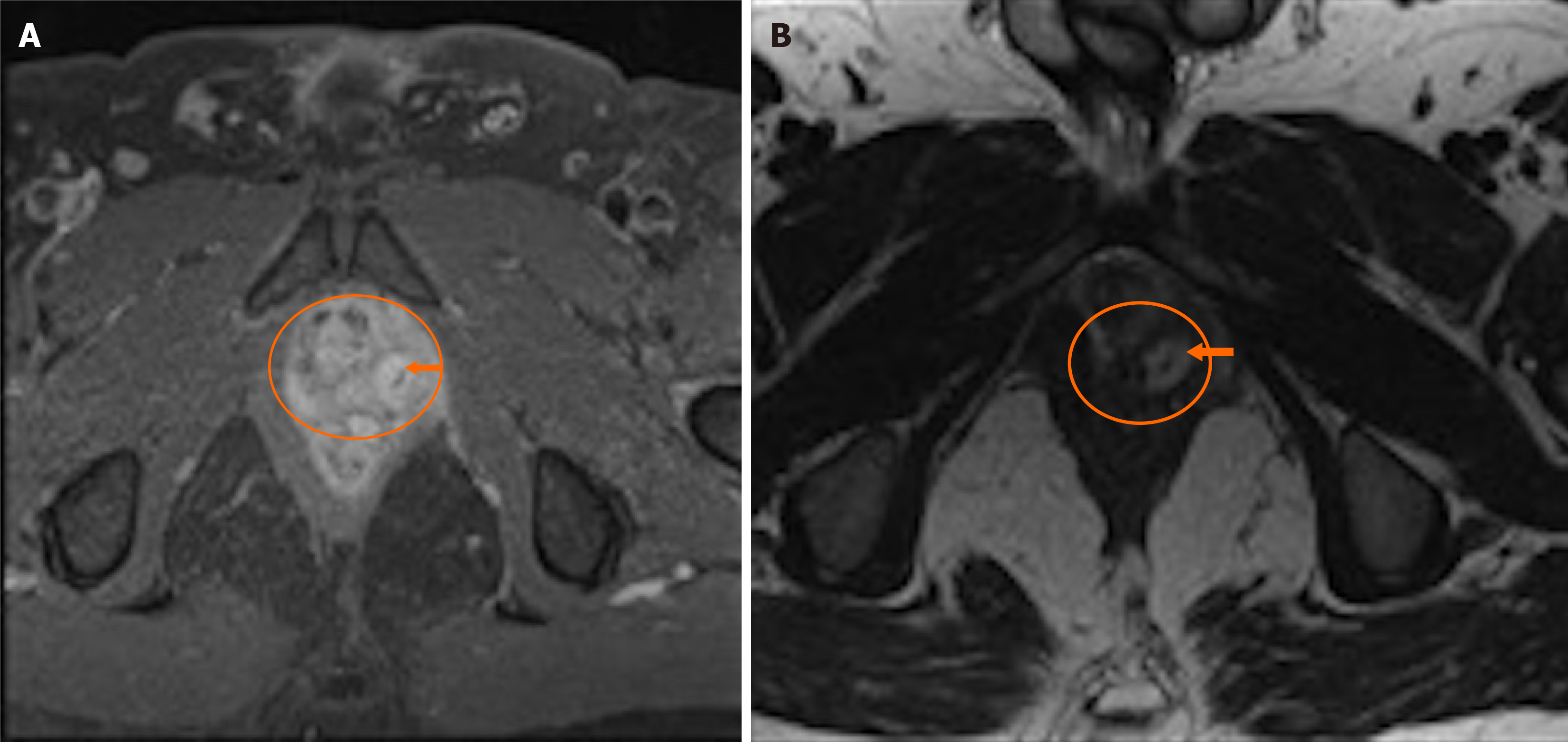

In addition, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to evaluate the soft tissues in greater detail, assessing the depth of the lesion, the volume of the collection, and its precise location relative to adjacent structures. The MRI revealed a fistulous tract with an internal opening extending from 1 to 43 mm from the anal verge, with an intramural abscess and a collection between the left iliococcygeal muscle and the left prostatic lobe. The lesion had a thick wall with peripheral enhancement after contrast administration, containing a 34 mm hypodense linear lesion within the abscess (foreign body) (Figure 3).

For the appropriate management of the case, interdisciplinary collaboration was carried out, involving specialties such as gastroenterology and general surgery. However, the coloproctology department led the process and performed the surgical intervention.

The MRI revealed a fistulous tract with an internal opening.

Based on these imaging study results, an anorectal endosonography was decided upon to better characterize the abscess and the foreign body. During the physical evaluation, the presence of external fistulous tracts was ruled out.

Anorectal endosonography reported a collection originating at the periphery of the left prostatic lobe and descending to the external anal sphincter without involving the internal anal sphincter. There was no external opening, suggesting it was located above the dentate line, on the left lateral wall.

With the analysis of these results, a decision was made in conjunction with the patient to proceed with surgical intervention. During surgery, a mucosal lesion measuring 15 mm × 15 mm was identified on the anterior left rectal wall just above the left puborectalis muscle at the lower boundary of the prostate, with the release of abundant fetid purulent material. A nodular mucosal lesion was resected, finding a necrotic-bordered orifice measuring 8 mm × 10 mm in the rectal wall. An explorer was introduced, revealing a cavity measuring 30 mm × 40 mm, which was debrided, releasing abundant necrotic material with pus and fetid tissue. Additionally, two fragments of a solid foreign body (bone vs vegetal fragments) were identified and removed (Figure 4).

Following the pathology report identifying mature bone tissue, the patient was reinterviewed. He recalled ingesting a chicken bone during a meal of fried chicken months earlier but had not considered it relevant at the time.

Due to the supra-elevator abscess, it was decided to debride and marsupialize the edges of the large rectal defect to ensure continuous drainage. Samples were sent for pathological study. The patient was discharged with a prescription for analgesics and antibiotics for continued outpatient management and follow-up.

Two weeks later, the patient attended a postoperative follow-up appointment, where he was found to be in very good general condition, stable, afebrile, calm, with controlled pain, and without signs of postoperative complications. The pathology results indicated that the fragments extracted from the rectal region were consistent with mature bone tissue. Therefore, the antibiotic treatment was continued for an additional two weeks, along with dietary and care recommendations.

Rectal foreign bodies are relatively rare, especially those resulting from accidental ingestion. However, voluntary insertions for sexual purposes or iatrogenic causes represent more frequent occurrences. Although the exact incidence of rectal foreign bodies due to accidental ingestion remains poorly documented, the rate is considered low. The most commonly ingested foreign objects include toothpicks, chicken bones, and plastic objects such as erasers or small toys. These objects may cause significant complications if left undiagnosed or untreated, including perforation, anal incontinence, fistulas, and abscess formation. Misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of rectal foreign bodies can lead to these potentially severe consequences, underscoring the clinical importance of timely identification and appropriate management[1,8,13].

Studies indicate that between 10% to 20% of foreign bodies fail to pass through the gastrointestinal tract and may become lodged in various sites, including the rectum. Though these cases are rare, complications such as perforation can occur in less than 1% of patients. This underscores the need for early and precise intervention to avoid life-threatening outcomes[1].

During the initial evaluation of the case, the patient reported nonspecific symptoms, including a one-year history of post-defecation anorectal pain associated with mild post-defecation rectorrhagia. The patient did not recall any specific trigger or the ingestion of any type of foreign body that could have caused these symptoms. Therefore, it was indeed a significant diagnostic challenge to elucidate the cause of these symptoms.

The first step in the evaluation and treatment of a patient with a rectal foreign body is to determine whether perforation has occurred. When perforation is suspected, it is crucial to determine as soon as possible if the patient is stable or unstable. Hypotension, tachycardia, severe abdominal pain, and fever are indicative of perforation. The physical examination should be detailed, looking for abnormalities that help identify the etiology, and a rectal examination should not be omitted[7,13]. In our patient, a lesion of non-mucosal origin was identified, which was tender to touch, without active bleeding, in the anterior left region above the left puborectalis muscle, requiring imaging studies to further characterize the lesion.

Given the patient's age (48 years), lack of prior colorectal cancer screening, and symptoms of one-year duration, a colonoscopy was prioritized to rule out neoplastic lesions. Retrospectively, a targeted rectoscopy might have been a more focused approach for identifying rectal lesions. The MRI findings suggested a fistulous tract extending from 1 to 43 mm from the anal verge; however, the lesion's location and inflammatory surroundings likely obscured its detection during colonoscopy, highlighting a limitation of this modality in such scenarios. When a foreign body is removed or absent in the rectal vault, rigid proctoscopy or endoscopic evaluation may reveal the rectal lesion or the foreign body located higher up in the rectosigmoid[3]. Computed tomography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging can further enhance the diagnostic ability to visualize smaller objects. In our patient, these imaging studies were necessary as the initial images showed that the duration of the retained bone had triggered a chronic inflammatory state, precluding any possibility of endoscopic recovery.

In clinically stable patients without evidence of perforation or peritonitis, the rectal foreign body should be removed in the emergency department or operating room. Depending on the size and shape of the object, various methods can be used. Most objects can be removed transanally, as was the case with our patient. If this is not possible or if safe extraction cannot be achieved, a transabdominal approach is used.

While rectal foreign bodies are a known clinical entity, reports of cases involving non-digestible objects, such as bone fragments, are rare. Existing literature provides limited case series, which often describe similar presentations but without a consistent approach to diagnosis and management. The variability in treatment strategies reflects the lack of standardized guidelines for managing these cases. As such, treatment often depends on the specifics of the case, including the location of the foreign body, the presence of complications such as abscesses, and the patient's overall health. The case presented here further underscores the need for a tailored approach to treatment, as no one-size-fits-all strategy has yet emerged in the literature.

Table 1 summarizes the key clinical features, diagnostic aids, and the results obtained from various diagnostic techniques used to evaluate a patient with anorectal pain and suspected foreign body ingestion. The diagnostic process, including imaging studies such as colonoscopy, MRI, and anorectal endosonography, contributed to identifying the lesion and the foreign body, ultimately guiding treatment decisions.

| Key clinical features | Diagnostic aids | Diagnostic results |

| Post-defecatory anorectal pain | Total colonoscopy | Erythematous, exophytic lesion in the distal rectum at the distal valve of Houston, proximal to the dentate line, measuring 13 x 10 mm with an inflammatory, lobulated, villous appearance, involving less than 20% of the circumference and not causing rectal lumen stenosis |

| Scant post-defecatory rectorrhagia | Contrast-enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance imaging | Fistulous tract with internal opening ranging from 1 to 43 mm from the anal verge, with an intramural abscess and a collection between the left iliococcygeal muscle and left prostatic lobe, with thick walls and peripheral enhancement post-contrast, containing a 34 mm hypodense linear lesion (foreign body) |

| Clinical presentation lasting 1 year | Anorectal endosonography | Collection originating from the periphery of the left prostatic lobe descending to the external anal sphincter without involving the internal anal sphincter. No external opening, seemingly located above the dentate line on the left lateral wall |

| Non-mucosal lesion, painful on palpation, no active bleeding | Not applicable | Not applicable |

This case underscores the importance of selecting appropriate diagnostic modalities based on patient history and clinical findings. While colonoscopy is valuable for screening, it may miss lesions outside the rectal lumen. Targeted rectoscopy, in combination with advanced imaging techniques like anorectal endosonography, can enhance diagnostic accuracy. Reassessing the patient’s history after pathology results can provide crucial insights into the etiology of rare presentations, such as rectal foreign bodies. Comprehensive evaluation, including detailed physical examinations and advanced imaging methods like magnetic resonance imaging and endosonography, is essential for accurate lesion characterization. The successful transanal removal and subsequent surgical debridement highlight the significance of personalized management strategies tailored to the patient's clinical condition and the foreign body’s characteristics. Regular postoperative follow-up is key for ensuring recovery and monitoring for complications. This case also emphasizes the need for patient education regarding the risks of ingesting foreign objects, especially in high-risk populations, and the value of a multidisciplinary approach for achieving optimal outcomes.

| 1. | Elmoghrabi A, Mohamed M, Wong K, McCann M. Proctalgia and colorectal stricture as the result of a 2-year transit of a retained rectal chicken bone: a case presentation and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr-2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coskun A, Erkan N, Yakan S, Yıldirim M, Cengiz F. Management of rectal foreign bodies. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singaporewalla RM, Tan DE, Tan TK. Use of endoscopic snare to extract a large rectosigmoid foreign body with review of literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:145-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goh BK, Chow PK, Quah HM, Ong HS, Eu KW, Ooi LL, Wong WK. Perforation of the gastrointestinal tract secondary to ingestion of foreign bodies. World J Surg. 2006;30:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alkandari AF, Alsarraf HM, Alkandari MF. Ingested Chicken Bone (Xiphoid Process) in the Anal Canal: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e35060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hong KH, Kim YJ, Kim JH, Chun SW, Kim HM, Cho JH. Risk factors for complications associated with upper gastrointestinal foreign bodies. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8125-8131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Cash DJ, Sadat MM, Abu-Own AS. Anorectal abscess and fistula caused by an ingested chicken bone. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1617-1618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Emir S, Ozkan Z, Altınsoy HB, Yazar FM, Sözen S, Bali I. Ingested bone fragment in the bowel: Two cases and a review of the literature. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:212-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tokunaga Y, Hata K, Nishitai R, Kaganoi J, Nanbu H, Ohsumi K. Spontaneous perforation of the rectum with possible stercoral etiology: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Today. 1998;28:937-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Loria A, Marianetti I, Cook CA, Melucci AD, Ghaffar A, Juviler P, Temple LK, Jones CMC, Fleming FJ. Epidemiology and healthcare utilization for rectal foreign bodies in United States adults, 2012-2021. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;69:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bhasin S, Williams JG. Rectal foreign body removal: increasing incidence and cost to the NHS. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2021;103:734-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fischer J, Krishnamurthy J, Hansen S, Reeves PT. Austere Foreign Body Injuries in Children and Adolescents: A Characterization of Penile, Rectal, and Vaginal Injuries Presenting to Emergency Departments in the United States From 2008 to 2017. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:e805-e811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cologne KG, Ault GT. Rectal foreign bodies: what is the current standard? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:214-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |