Published online Jun 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.103055

Revised: December 21, 2024

Accepted: January 27, 2025

Published online: June 26, 2025

Processing time: 112 Days and 23 Hours

The primary lymphomas of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) of the gallbladder (GB) is an extremely rare of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Many patients exhibit symptoms like gallstone disease, and in some cases, the lymphoma may be detected through imaging even without apparent symptoms. Only 19 cases of primary MALT lymphoma in the GB have been previously reported. Differential diagnosis from typical GB carcinoma based solely on imaging findings can be challenging, and definitive diagnosis often requires surgical intervention.

We present a patient in an 82-year-old man who was initially diagnosed with prostate cancer but incidentally detected GB wall thickening from magnetic resonance imaging conducted for prostatic surgery and subsequent radical cholecystectomy revealed primary MALT lymphoma of the GB. The patient was followed up by a medical oncologist, and after discussion, the decision was made to continue observation with close monitoring without systemic chemotherapy given the asymptomatic presentation. The patient has been free of recurrence for 16 months after the surgery. Although precise diagnosis before the surgery was difficult in this case, preoperative examinations revealed a submucosal tumor-like lesion.

MALT lymphoma of GB remains little known in many previous studies. It is really difficult to preoperatively diagnose. The combination of clinical presentation, postoperative histology and immunohistochemistry contribute to diagnosis and carry out appropriate management.

Core Tip: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the gallbladder (GB) often presents symptoms similar to cholecystitis. In addition, diagnosis and treatment through surgical resection should not be delayed, as distinguishing it from GB cancer on imaging is difficult. The prognosis is favorable after surgical resection, allowing monitoring with appropriate follow-up.

- Citation: Lee MR, Jang KY, Yang JD. Primary mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the gallbladder: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(18): 103055

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i18/103055.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.103055

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is characterized by the neoplastic proliferation of B-cells within the marginal zone of lymphoid tissue, classifying it as a marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. MALT lymphoma can manifest in various extranodal sites, including the stomach, gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, salivary glands, lungs, and skin[1]. In contrast to nodal lymphomas, MALT lymphomas pose diagnostic challenges owing to their diverse organ involvement and nonspecific symptoms.

The incidence of primary MALT lymphoma in the gallbladder (GB) is exceptionally rare, making it challenging to determine, with few documented cases[1-3]. Here, we present a case of MALT lymphoma of the GB and provide a review of the pertinent literature.

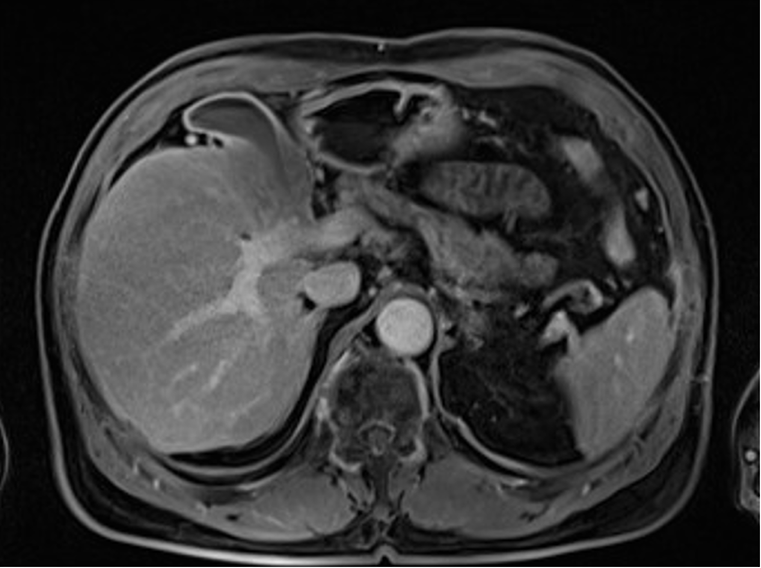

An 82-year-old male with a history of prostate cancer was found incidentally to have thickening of the GB wall (9 mm) involving the liver parenchyma on prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 1).

The patient had no specific symptoms of chronic or acute cholecystitis, such as abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, or indigestion. He was hospitalized for further examination because of suspected GB cancer or adenoma.

The patient was diagnosed with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and liver cirrhosis 30 years ago. Twenty years prior, he underwent left lateral hepatic sectionectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and was followed-up for five years, with no HCC recurrence.

The patient's family history had no notable findings.

Physical examination revealed a soft and non-tender abdomen without rebound tenderness or Murphy’s sign.

Laboratory tests revealed the following results: White blood cell count, 6710/μL; red blood cell count, 427 × 104/μL; platelet count, 286 × 103/μL; total protein, 7.6 g/dL; albumin, 4.8 g/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 22 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 16 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase, 79 IU/L; gamma-glutamyl transferase, 38 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase, 165 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.60 mg/dL; direct bilirubin, 0.21 mg/dL; and C-reactive protein, 0.02 mg/dL.

The HBV markers were HBsAg-negative, Anti-HBe-positive, and HBsAb-positive, with an HBV DNA titer of 695 IU/mL. Tumor markers were all normal: carcinoembryonic antigen 2.68 ng/mL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9 9.27 U/mL; total prostate-specific antigen 3.2 ng/mL; alpha-fetoprotein 2.30 ng/mL; and prothrombin induced by vitamin K absence-II 27 mAU/mL.

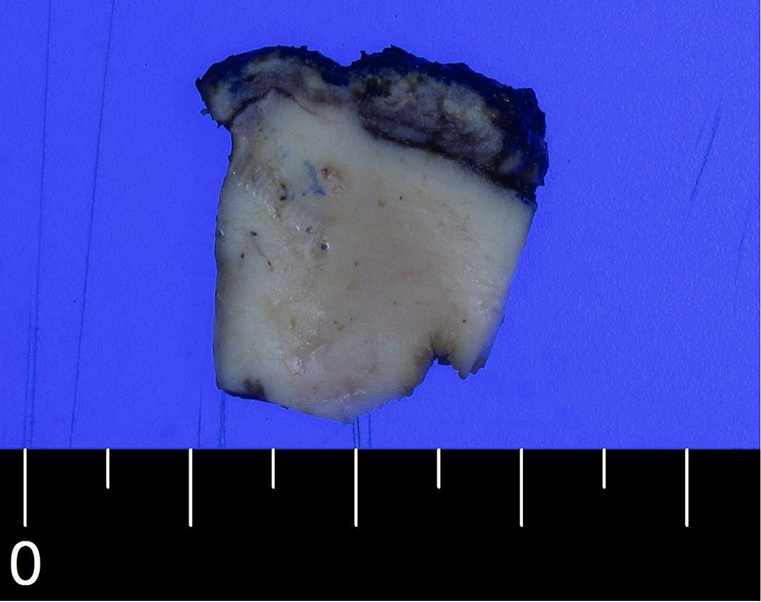

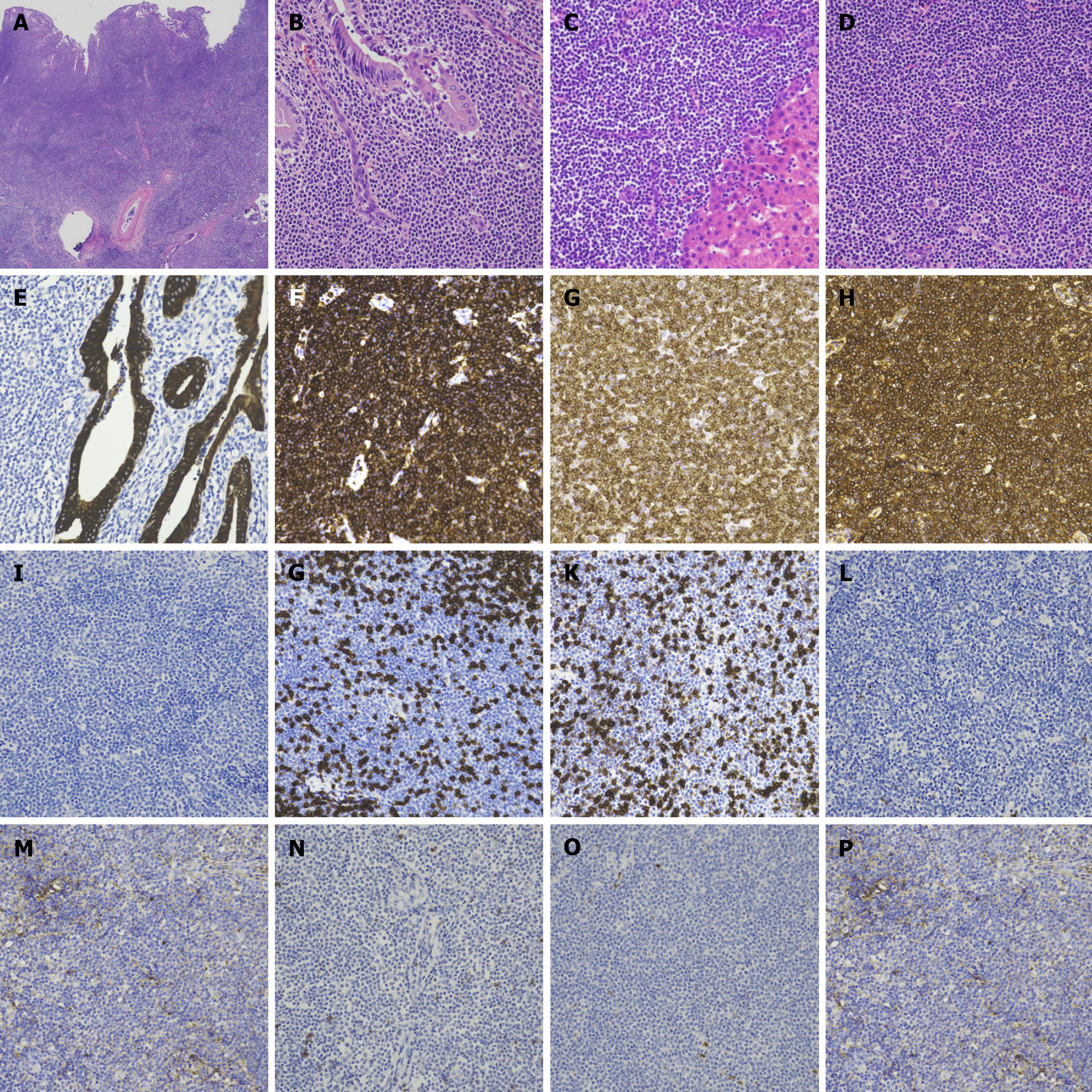

Macroscopically, the GB wall appeared broadly thickened by approximately 1 cm (Figure 2). Microscopic examination revealed the infiltration of lymphoid tumor cells throughout all layers of the GB wall (Figure 3A). These tumor cells also infiltrated the GB mucosa and liver parenchyma (Figure 3B and C), exhibiting a diffuse pattern with small and inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 3D). The cells infiltrated the cytokeratin-positive GB mucosa; however, no lymphoepithelial lesions were observed (Figure 3E).

Immunohistochemical staining showed that the tumor cells were positive for CD20, BCL2, and κ light chain (Figure 3F–H). However, they were negative for TdT, CD3, CD5, CD10, BCL6, CD23, cyclin D1, and λ light chain (Figure 3I–P). The tumor cells had a Ki-67 index of 10%.

MRI revealed GB wall thickening (10 mm) with low intensity relative to the liver parenchyma on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 1).

A thickened GB wall (10 mm) was also observed on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) with homogeneous enhancement in the arterial, portal, and delayed phases (Figure 4). CECT also showed laminar enhancement in the liver bed, indicating hepatic invasion. These imaging findings did not conclusively distinguish the lesion as malignant. There were no specific findings, such as metastasis, on chest CT.

Based on these findings, the patient received a diagnosis of GB MALT lymphoma.

The patient underwent an open cholecystectomy with a sleeve resection of the liver and surrounding lymph nodes dissection. During surgery, a frozen biopsy of the cystic duct confirmed a diagnosis of lymphoma. However, additional bile duct resection was not considered, and surgery was performed.

Postoperatively, positron emission tomography/CT, bone marrow biopsy, and endoscopy were performed, revealing stage I disease. Testing for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and HCV infections, which are known causes of MALT lymphoma, was negative. Given the patient’s advanced age, systemic chemotherapy and radiation therapy were not pursued. Instead, the patient is monitored in the outpatient setting, with follow-up visits scheduled every 3–6 months for five years, followed by annual checkups. The patient remained recurrence-free for 16 months postoperatively.

Malignant lymphoma of GB accounts for only 0.1 to 0.2% of all GB cancer patients. The most common subtype is the MALT lymphoma account for 40%, followed by diffuse large B-cell lymphoma[1,4]. MALT lymphoma accounts for approximately 8% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, predominantly affecting middle-aged and older individuals (ranging from 31 to 84 years), especially women (65%)[4]. MALT lymphoma arises in mucosal tissues and can manifest in various organs. They are divided into gastric (50%) and non-gastric lymphomas [salivary glands (13%), skin (6%), orbits (5%), thyroid gland, lungs and mammary gland] depending on its location[4]. However, involvement of the GB is rare, with only approximately 19 cases reported in the English literature[1-3].

Primary MALT lymphoma of the GB has an unclear pathogenesis due to the absence of lymphoid tissue in the GB wall. One hypothesized suggests that lymphocyte migration may occur as a result of bacterial infections, such as chronic cholecystitis or cholelithiasis. In addition, antigenic stimulation may lead to the formation of a fusion protein called API2-MALT1, which induces antigen-independent cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis through NF-κB-mediated upregulation of anti-apoptotic genes, ultimately contributes to the development of MALT lymphoma[5]. Another possible mechanism is that consistent chronic inflammation results in irreversible genetic rearrangements, which inactivate the cell’s response to IL-2 regulation, eventually helping to develop MALT lymphoma[6].

In most cases, surgical resection is performed to distinguish between cholecystitis, GB cancer, and lymphoma, with final diagnosis confirmed by immunostaining. In chronic cholecystitis, immunohistochemistry (IHC) reveals a mononuclear cell infiltrate composed of both T and B lymphocytes, and macrophages[7]. GB cancer exhibits specific markers associated with prognosis and tumor behavior. The IHC in GB cancer shows overexpression of PLA2GA, particularly in early-stage GB cancer and positive staining for MRP2, CXCR4 and PD-L1, which is associated with better prognosis in late-stage tumor[8]. MALT lymphoma displays characteristic B-cell markers and lymphoepithelial lesions that atypical lymphocytes infiltrating all layers of the GB wall. The IHC in MALT lymphoma of GB demonstrates positive staining for CD 20 and BCL-237, otherwise negative staining for CD3, CD5, BCL-6, CD43, and cyclin D13. It has Ki67 proliferation index (PI) of approximately 5%[1,3]. These distinct immunostaining profiles aid in accurate diagnosis and guide appropriate treatment strategies for each condition.

Ki-67 is a nuclear protein that plays a crucial role in assessing tumor proliferation characteristics in gastric MALT lymphoma. The majority (85%) of gastric MALT lymphomas have a Ki-67 index ≤ 20%[9]. Also, The Ki-67 PI is used to determine the growth fraction of tumors and has significant implications for prognosis and treatment decisions. The Ki-67 PI is particularly useful in differentiating low-grade MALT lymphomas from high-grade lymphomas. A cut-off value of 45% can help differentiate indolent (low-grade) from aggressive (high-grade) lymphomas[10]. The assessment of Ki-67 in gastric MALT lymphoma can provide valuable information for monitoring patients at risk. But, in non-gastric MALT lymphoma, there are no studies on the roles.

As imaging alone does not reliably distinguish among these diagnoses, regular checkups are necessary for asymptomatic GB wall thickening. The common United States features of primary GB lymphoma present as thickening of the GB wall or a soft tissue mass located in GB with or without gallstone, which has lower echo compared to GB carcinoma[11]. According to reports from several cases, MRI findings for GB MALT lymphoma typically shown low intensity on T1-weighted sequences and high intensity on T2-weighted sequences compared to the liver parenchyma. The difference between GB cancer and MALT lymphoma in MRI is that the T2-weighted sequence signal intensity of GB MALT lymphoma is lower and more uniform compared to GB cancer[11,12].

The treatment strategy for MALT lymphoma depends on the location of the primary lesions. The most common type of MALT lymphoma, gastric MALT lymphoma, is caused by H. pylori infection, and can be successful resolved with H. pylori eradication therapy, leading to complete remission in 100% of cases[13]. In contrast, for MALT lymphoma originating in the GB, no treatment policy has been established, and surgery is the only diagnosis and treatment. With surgical treatment, prognosis is better, and only one of the 20 cases documented cases showed recurrence in the stomach five years after surgical resection, requiring chemotherapy[14]. The targeted approaches could potentially be applicable to GB MALT lymphoma, especially in cases where molecular profiling identifies relevant mutations or overexpression of these targets, such as EGFR inhibitors, FGFR inhibitors, HER2-targeted therapies, and PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors[15]. Given the slow-growing nature of MALT lymphoma and its favorable prognosis following cholecystectomy, watchful waiting may be appropriate in asymptomatic cases; however, cholecystectomy is recommended for cases with symptomatic or significant GB wall thickening due to its good prognosis and difficulty distinguishing it from GB cancer.

Only 19 cases of MALT lymphoma of the GB have been reported in the English literature (Table 1). Including the present case, MALT lymphoma of the GB is more prevalent in women (60%), and the age of occurrence is widely diverse, ranging from 31 to 84 years (median, 74 years). Most patients present with symptoms resembling acute cholecystitis, right upper quadrant pain, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, 65% of cases are associated with cholelithiasis. However, in this case, it was accidentally detected as asymptomatic. It was confirmed as GB MALT lymphoma after surgical treatment because it was difficult to differentiate it from GB cancer radiologically. With the exception of one, they underwent cholecystectomy and there was no recurrence during the observation period.

| No | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Gallbladder stone | Radiological findings | Treatment | Recurrence | Ref. |

| 1 | 80 | M | - | N | Fairly nodular proliferation | - | Death from other causes | Honda et al[1] |

| 2 | 60 | F | RUQ pain, fever, nausea and vomiting | Y | Distended and thin | Cholecystectomy | No at 6 months | |

| 3 | 75 | F | RUQ pain, nausea and vomiting | Y | Mass | Cholecystectomy | No at 12 months | |

| 4 | 82 | M | Jaundice and abdominal pain | Y | Wall thickening | Cholecystectomy | Death from other causes | |

| 5 | 74 | F | RUQ pain and nausea | Y | - | - | - | |

| 6 | 58 | F | Abdominal pain | N | Polypoid lesions | Cholecystectomy | No at 24 months | |

| 7 | 65 | F | RUQ pain | N | - | Cholecystectomy (Chemotherapy) | Recurrence at 96 months in stomach | |

| 8 | 31 | F | RUQ pain | N | Wall thickening | Cholecystectomy | - | |

| 9 | 60 | F | Abnormal liver function tests | Y | - | Cholecystectomy | No at 3 months | |

| 10 | 51 | F | RUQ pain | Y | - | Cholecystectomy | No at 2 months | |

| 11 | 75 | F | RUQ pain | Y | Wall thickening | Cholecystectomy | No at 16 months | |

| 12 | 78 | M | Nothing | N | Polypoid lesions | Cholecystectomy | No at 3 months | |

| 13 | 74 | M | - | Y | - | - | - | |

| 14 | 84 | F | - | N | - | - | - | |

| 15 | 65 | F | RUQ pain and nausea | Y | Polypoid lesions | Cholecystectomy | No at 3 months | |

| 16 | 73 | M | Abdominal pain and distension | Y | Wall thickening | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | No at 12 months | |

| 17 | 80 | M | RUQ pain | Y | Mass | Cholecystectomy | No at 39 months | |

| 18 | 39 | M | RUQ pain, fever, weight loss and fatigue | N | Mass | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | - | Papamichail et al[3] |

| 19 | 73 | F | RUQ pain | Y | - | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | No at 1 months | Farmah et al[2] |

| 20 | 82 | M | Nothing | N | Wall thickening | Radical cholecystectomy | No at 16 months | Present case |

MALT lymphoma originating from the GB is a rare disease with no established diagnostic tools. Given its clinical similarity to GB cancer and favorable prognosis following surgical resection, timely surgical intervention is recommended for both diagnosis and treatment.

| 1. | Honda M M D, Furuta Y M D Ph D, Naoe H M D Ph D, Sasaki Y M D Ph D. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma of the gallbladder and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Farmah P, Mehta AH, Vu AH, Tchokouani LS, Nazir S. Extranodal Marginal Zone Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma of the Gallbladder: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e35825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Papamichail M, Dimitrokallis N, Gogoulou I, Nomikos A, Ioannides C. Primary Large Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (MALT) Lymphoma of the Gallbladder. Cureus. 2022;14:e23799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Devizzi L, Giardini R, Pinotti G, Capella C, Zinzani PL, Pileri S, López-Guillermo A, Campo E, Ambrosetti A, Baldini L, Cavalli F; International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101:2489-2495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bagwan IN, Ping B, Lavender L, de Sanctis S. Incidental presentation of gall bladder MALT lymphoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2011;42:61-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cho YH, Byun JH, Kim JH, Lee SS, Kim HJ, Lee MG. Primary malt lymphoma of the common bile duct. Korean J Radiol. 2013;14:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jeffrey GP, Reed WD, Carrello S, Shilkin KB. Histological and immunohistochemical study of the gall bladder lesion in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 1991;32:424-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tittarelli A, Barría O, Sanders E, Bergqvist A, Brange DU, Vidal M, Gleisner MA, Vergara JR, Niechi I, Flores I, Pereda C, Carrasco C, Quezada-Monrás C, Salazar-Onfray F. Co-Expression of Immunohistochemical Markers MRP2, CXCR4, and PD-L1 in Gallbladder Tumors Is Associated with Prolonged Patient Survival. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zeggai S, Harir N, Tou A, Sellam F, Mrabent MN, Salah R. Immunohistochemistry and scoring of Ki-67 proliferative index and p53 expression in gastric B cell lymphoma from Northern African population: a pilot study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:462-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Broyde A, Boycov O, Strenov Y, Okon E, Shpilberg O, Bairey O. Role and prognostic significance of the Ki-67 index in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:338-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ono A, Tanoue S, Yamada Y, Takaji Y, Okada F, Matsumoto S, Mori H. Primary malignant lymphoma of the gallbladder: a case report and literature review. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:e15-e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamamoto T, Kawanishi M, Yoshiba H, Kanehira E, Itoh H. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gallbladder. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:S86-S87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Violeta Filip P, Cuciureanu D, Sorina Diaconu L, Maria Vladareanu A, Silvia Pop C. MALT lymphoma: epidemiology, clinical diagnosis and treatment. J Med Life. 2018;11:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chim CS, Liang R, Loong F, Chung LP. Primary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the gallbladder. Am J Med. 2002;112:505-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou Y, Yuan K, Yang Y, Ji Z, Zhou D, Ouyang J, Wang Z, Wang F, Liu C, Li Q, Zhang Q, Li Q, Shan X, Zhou J. Gallbladder cancer: current and future treatment options. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1183619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |