Published online Jun 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.101612

Revised: December 15, 2024

Accepted: January 23, 2025

Published online: June 26, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 21.5 Hours

Pancreatic tuberculosis (PTB) is a rare disease, even in immunocompetent hosts. Abdominal tuberculosis involving the pancreatic head and peripancreatic areas may simulate pancreatic head carcinoma.

We present the case of a 32-year-old man who was admitted to our hospital for intermittent epigastric pain and weight loss. A computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a mass in the head of the pancreas. The lesion was initially diagnosed as pancreatic head carcinoma on abdominal ima

The present case is reported to emphasize the importance of including PTB in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic lesions.

Core Tip: Pancreatic tuberculosis (PTB) is a rare and challenging condition, particularly in immunocompetent individuals. It commonly presents with nonspecific symptoms that resemble those of pancreatic malignancies, complicating the diagnosis based solely on clinical and imaging findings. Therefore, a thorough diagnostic approach, including histopathological confirmation, is crucial for accurate identification. Clinicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for PTB, especially in areas with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, and include it in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic lesions to avoid delays in treatment.

- Citation: Ma L, Wang KP, Jin C. Abdominal tuberculosis with pancreatic head involvement mimicking pancreatic malignancy in a young man: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(18): 101612

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i18/101612.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i18.101612

Abdominal tuberculosis involving the pancreas and peripancreatic lymph nodes is an uncommon manifestation within clinical medicine. This form of tuberculosis typically presents insidiously, with nonspecific constitutional symptoms such as abdominal pain, anorexia, weakness, fever, weight loss, and night sweats[1]. Distinguishing pancreatic tuberculosis (PTB) from pancreatic carcinoma presents a substantial challenge due to overlapping clinical presentations. However, a key distinguishing factor is the relatively infrequent occurrence of obstructive jaundice in PTB compared to its more prevalent presence in pancreatic head carcinoma[2-4]. Laboratory assessments, encompassing liver function tests, hematologic parameters, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, frequently fall short of providing definitive diagnostic insights[5].

The diagnostic process for PTB is notably complex, often necessitating laparotomy for a conclusive diagnosis in the majority of reported cases[6] In this study, we present a compelling case of a male patient displaying a pancreatic head mass on abdominal imaging suggestive of pancreatic head cancer, ultimately diagnosed with PTB through surgical intervention. This case underscores the critical role of surgical exploration in unraveling the intricacies of abdominal tuberculosis involving the pancreas, emphasizing the significance of accurate diagnosis for timely and appropriate management[7].

A 32-year-old man presented with a 1-month history of intermittent epigastric pain, anorexia, and weight loss of 5 kg.

The patient presented with intermittent epigastric pain, described as a dull ache without clear triggers, which began 1 month prior. The pain was mild, with no distinct pattern of exacerbation or relief. It was not associated with nausea, vomiting, chills, fever, diarrhea, or other concomitant symptoms. However, the patient experienced a reduced appetite, and although the intermittent abdominal pain remained stable for 1 month, there was a weight loss of 5 kg.

The patient had a past medical history of chronic erosive gastritis for 1 year, for which he was administered antacid drugs discontinuously.

The patient denied any history of specific personal illnesses and family history.

The patient’s temperature was 37.3 °C; heart rate, 72 beats per minute; respiration rate, 17 breaths per minute; and blood pressure, 114/66 mmHg. The abdomen was flat and soft, with no visible skin abnormalities or other positive signs. There was no friction rub, mild tenderness in the epigastric region, no rebound tenderness, and no palpable enlargement of surface lymph nodes.

Laboratory examination at the time of admission revealed that the complete blood count, liver function tests, bilirubin and amylase levels, serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9, serum CA 12-5, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels were all within normal limits. The findings on chest radiography were also normal.

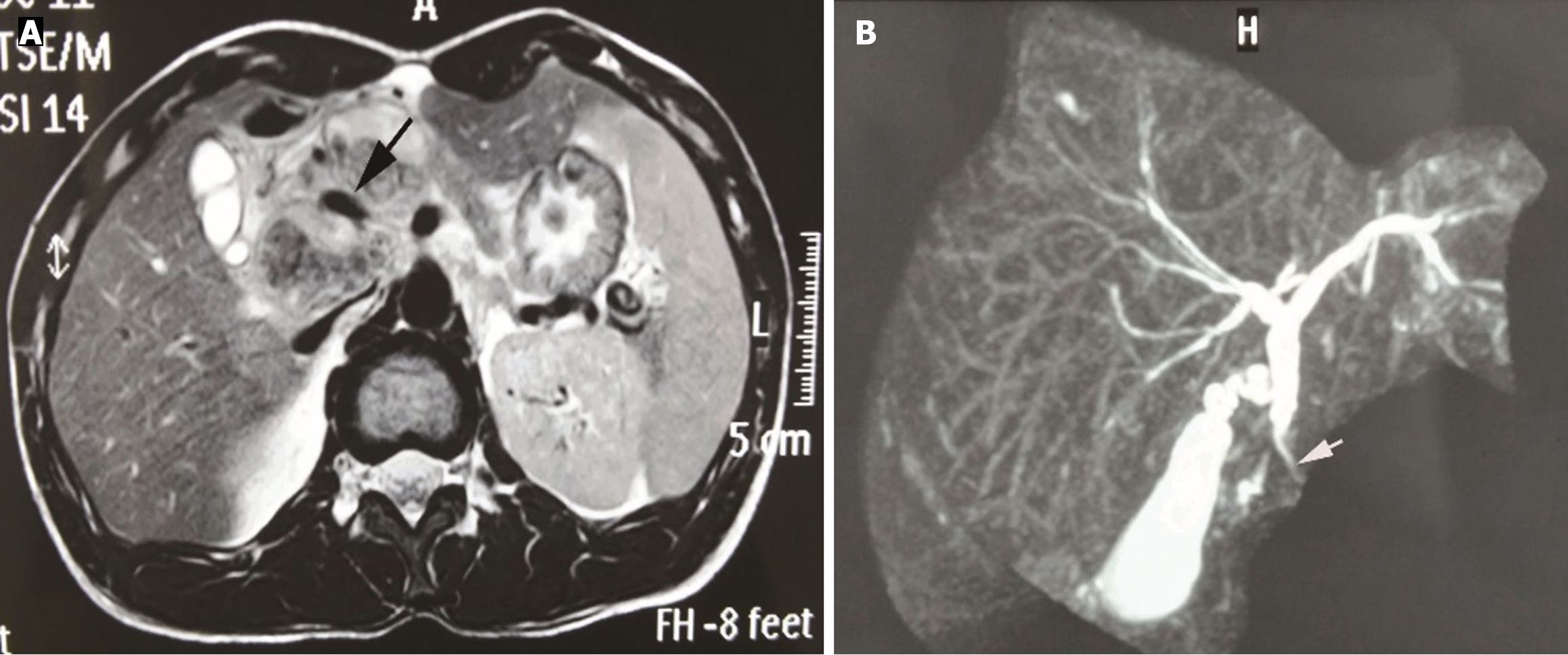

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an ill-defined 35 mm × 30 mm mass lesion in the head of the pancreas. The mass exhibited inhomogeneous enhancement, with the portal vein encased and compressed by the mass (Figure 1), mimicking a pancreatic head carcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed local stenosis of the portal vein due to compression by the lesion (Figure 2; black arrow). Stricture of the distal common bile duct was observed on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Figure 2; white arrow), without apparent dilatation of the proximal common bile duct, intrahepatic bile duct, or pancreatic duct. In addition, several enlarged lymph nodes were identified in the retroperitoneum.

PTB.

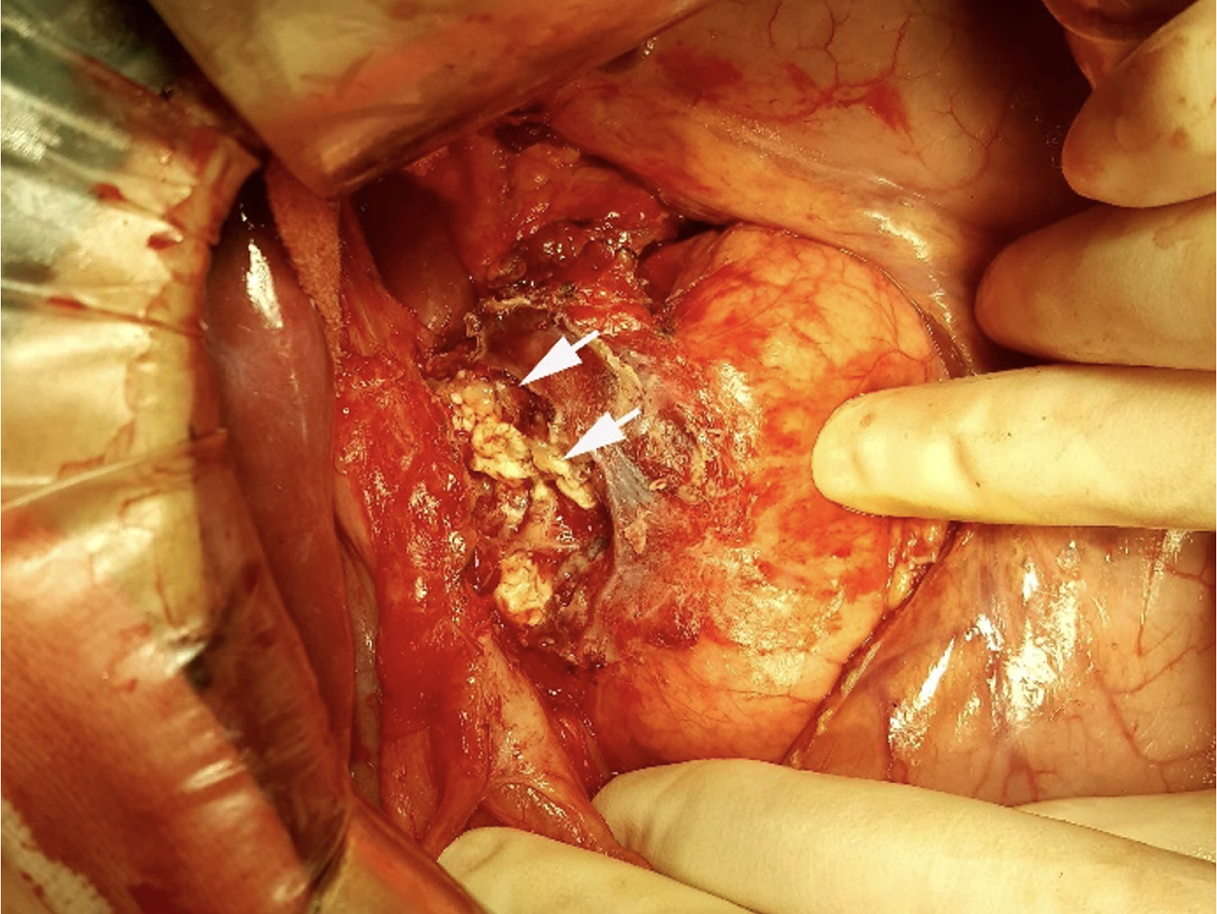

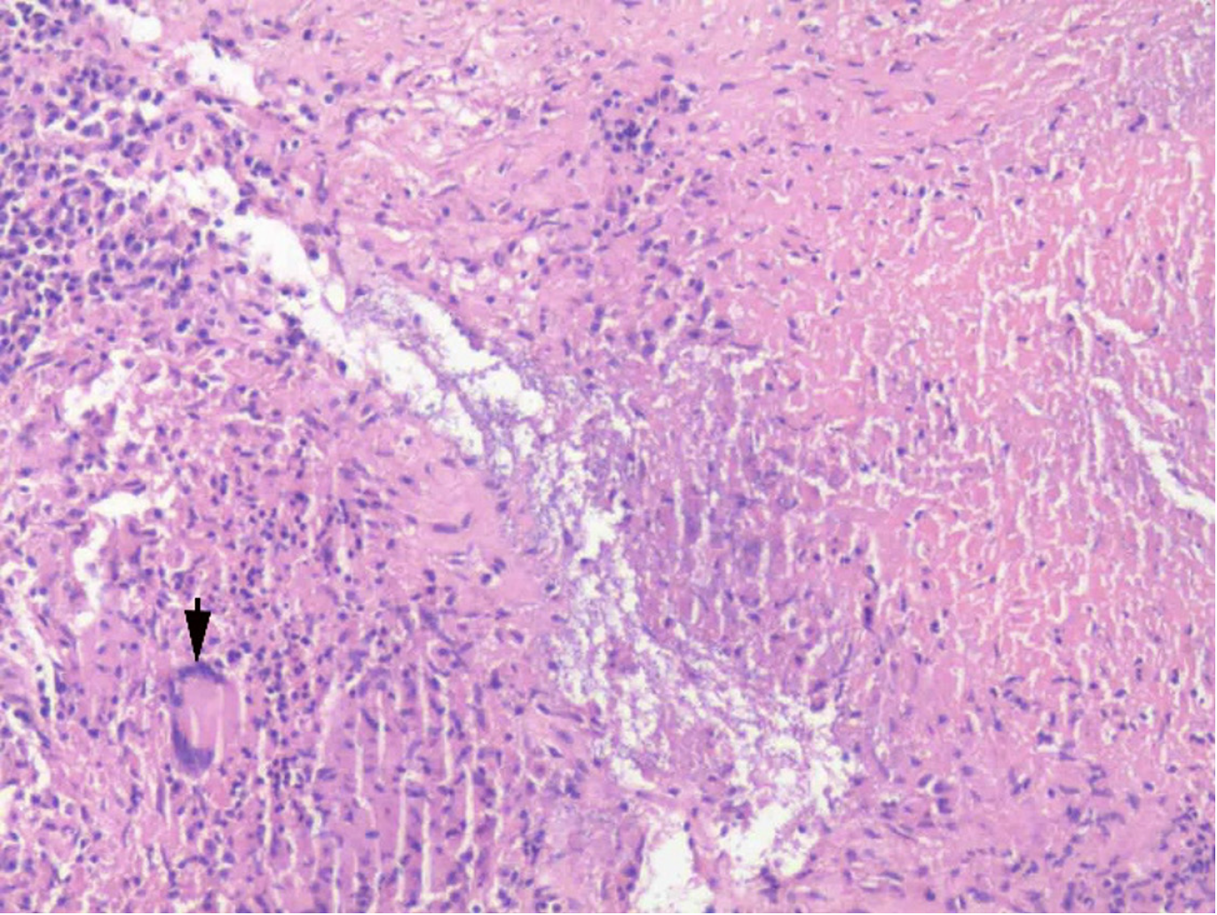

The appearance of CT and MRI scans indicated a possible diagnosis of a pancreatic malignancy. Therefore, an exploratory laparotomy with pancreaticoduodenectomy as a contingency was planned. Intraoperatively, a mass was identified above the pancreatic head, comprising caseous necrotic tissue (Figure 3). An intraoperative frozen section biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculous lymphadenitis. Histopathological examination revealed a mass composed of epithelioid cells and occasional multinucleated giant cells, exhibiting caseous necrosis (Figure 4). However, the test for acid-fast bacilli was negative. Antituberculosis therapy was administered to the patient after surgery.

The patient made a full recovery and was subsequently discharged.

Tuberculosis is a multisystem infectious disease, primarily affecting the lungs, with abdominal tuberculosis being a common extrapulmonary form. PTB, involving the pancreas and peripancreatic lymph nodes, is rare. Its clinical manifestations typically begin insidiously with nonspecific symptoms, including abdominal pain, anorexia, weakness, fever, weight loss, and night sweats[5]. Obstructive jaundice, common in pancreatic head carcinoma, is uncommon in PTB[7-9]. Laboratory findings often show abnormal liver function, anemia, leukocytosis, or elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, but are generally nonspecific[10].

PTB is a rare extrapulmonary manifestation of tuberculosis, with its incidence varying significantly across different regions. PTB is more commonly reported in areas with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, such as Southeast Asia, Africa, and parts of South America. Individuals who are immunocompromised, including those with human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, diabetes mellitus, or those receiving immunosuppressive therapy, are at an increased risk of developing PTB. However, the true incidence remains underreported due to its rarity and the diagnostic challenges involved in distinguishing PTB from pancreatic malignancies or other pancreatic disorders[11].

The diagnosis of PTB is challenging in most reported cases, particularly before laparotomy[12]. Since PTB is curable with antituberculosis therapy, obtaining a definitive diagnosis through imaging is critical to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions. However, imaging studies often struggle to reliably distinguish PTB from pancreatic malignancies or other pancreatic conditions. CT is the standard diagnostic imaging modality and is widely employed in clinical practice. Despite its broad application, the CT features of PTB—such as low-density lesions, heterogeneous or peripheral rim enhancement, and calcifications—are nonspecific and can closely resemble those of pancreatic carcinoma[13,14]. Peripheral rim enhancement on CT, often indicative of lymphadenitis, reflects central caseous necrosis surrounded by active inflammation in infected lymph nodes[15].

MRI can provide complementary information to CT in diagnosing PTB. Typical MRI findings include lesions with low intensity on T1-weighted images and high intensity on T2-weighted images, along with peripheral rim enhancement on post-contrast T1-weighted images[16]. Unlike pancreatic malignancies, PTB rarely causes bile duct dilatation on MRCP, even for lesions located in the pancreatic head. Similarly, vascular involvement, a feature commonly associated with advanced pancreatic malignancies, has also been reported in PTB, complicating its differentiation based on imaging alone[6,10,14]. Abdominal imaging of PTB may reveal solid or cystic lesions, typically in the pancreatic head. Therefore, the main differential diagnoses include mucinous/serous cystadenoma, cystic neuroendocrine tumor, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, whereas PTB mimicking pancreatic abscess has also been reported[13].

Given these limitations of imaging, histological or bacteriological confirmation is essential for a definitive diagnosis. Cytological examination of PTB typically reveals caseous necrosis, granulomatous inflammation, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes; however, acid-fast bacilli are rarely observed[17]. Biopsy techniques, including percutaneous ultrasound- or CT-guided biopsy and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), play a crucial role in confirming PTB. While EUS-FNA is widely recognized as safe and effective, it carries risks such as insufficient sample retrieval and complications in suspected malignancy cases[3,9,10,18] To enhance the early recognition of PTB, several strategies can be implemented. First, increasing clinical awareness of PTB, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, is vital. Second, integrating advanced imaging modalities such as diffusion-weighted MRI with histological and microbiological diagnostics can significantly improve diagnostic accuracy. Finally, adopting a multidisciplinary approach involving radiologists, gastroenterologists, and pathologists can accelerate diagnosis and treatment, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

The hallmark histological features of PTB include granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis. These granulomas are typically composed of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated Langhans-type giant cells, and a peripheral lymphocytic rim. The presence of caseous necrosis is a key distinguishing feature of PTB, as it is absent in other granulomatous diseases, such as sarcoidosis. Special staining methods, such as Ziehl-Neelsen staining for acid-fast bacilli, can detect mycobacterial organisms, although their sensitivity varies. Diagnostic accuracy can be further enhanced using immunohistochemical staining for mycobacterial antigens or molecular techniques such as PCR, particularly in paucibacillary cases[2,19].

This case underscores the importance of considering PTB as a differential diagnosis, even in immunocompetent individuals, where clinical and imaging findings may resemble those of malignancy. It emphasizes the progress in understanding PTB, particularly the necessity of a thorough diagnostic approach, which includes histopathological confirmation. The study also highlights the critical role of imaging in clinical decision-making, although these techniques have limitations in distinguishing PTB from pancreatic malignancies. Future research should aim to develop more accurate, non-invasive diagnostic tools, such as advanced imaging technologies or biomarkers, to facilitate early detection of PTB. Additionally, optimizing treatment regimens for PTB, especially in cases with atypical presentations or complications, warrants further investigation. It is crucial to emphasize the significance of PTB in younger, immunocompetent individuals, as this group is often overlooked in the differential diagnosis, which may delay appropriate treatment.

We are very grateful to our colleagues from the Department of Imaging for providing the computed tomography pictures.

| 1. | Mao XB, Li N, Huang ZS, Ding CM, Bao WJ, Fan J, Li HL. (18)F-FDG PET-CT Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Celiac Lymph Nodes. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:1335-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ben Hammouda S, Chaka A, Njima M, Korbi I, Zenati H, Zakhama A, Hadhri R, Zouari K. Primary pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic body cancer. A case report and review of the literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;58:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yu D, Li X, Gong J, Li J, Xie F, Hu J. Left-sided portal hypertension caused by peripancreatic lymph node tuberculosis misdiagnosed as pancreatic cancer: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 4. | Jemni I, Akkari I, Mrabet S, Jazia EB. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking pancreatic cancer in an immunocompetent host: An elusive diagnosis. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:1575-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Soni A, Tyagi R, Selhi PK, Sood A, Sood N. Pancreatic tuberculosis: A close mimicker of malignancy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30:1001-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kaur M, Dalal V, Bhatnagar A, Siraj F. Pancreatic Tuberculosis with Markedly Elevated CA 19-9 Levels: A Diagnostic Pitfall. Oman Med J. 2016;31:446-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | García Del Olmo N, Boscà Robledo A, Penalba Palmí R, Añón Iranzo E, Aguiló Lucía J. Primary peripancreatic lymph node tuberculosis as a differential diagnosis of pancreatic neoplasia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:528-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sun PJ, Lin Y, Cui XJ. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis with elevated CA 19-9 levels masquerading as a malignancy: A rare case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | ForŢofoiu MC, Popescu DM, Pădureanu V, Dobrinescu AC, Dobrinescu AG, Mită A, Foarfă MC, Bălă VS, Muşetescu AE, Ionovici N, ForŢofoiu M. Difficulty in positive diagnosis of ascites and in differential diagnosis of a pulmonary tumor. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2017;58:1057-1064. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Yamada R, Inoue H, Yoshizawa N, Kitade T, Tano S, Sakuno T, Harada T, Nakamura M, Katsurahara M, Hamada Y, Tanaka K, Horiki N, Takei Y. Peripancreatic Tuberculous Lymphadenitis with Biliary Obstruction Diagnosed by Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided Fine-needle Aspiration Biopsy. Intern Med. 2016;55:919-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Machicado JD, Papachristou GI. Pancreatogenic diabetes, acute pancreatitis management, and pancreatic tuberculosis: Appraising the present and setting goals for the future. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:365-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee YJ, Hwang JY, Park SE, Kim YW, Lee JW. Abdominal tuberculosis with periportal lymph node involvement mimicking pancreatic malignancy in an immunocompetent adolescent. Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44:1450-1453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Naisbitt CJ, Filobbos R, Bonington A, O'Reilly D. A space occupying lesion masquerading as pancreatic carcinoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Khaniya S, Koirala R, Shakya VC, Adhikary S, Regmi R, Pandey SR, Agrawal CS. Isolated pancreatic tuberculosis mimicking as carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2010;3:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cho SB. Pancreatic tuberculosis presenting with pancreatic cystic tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim JB, Lee SS, Kim SH, Byun JH, Park DH, Lee TY, Lee BU, Jeong SU, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH. Peripancreatic tuberculous lymphadenopathy masquerading as pancreatic malignancy: a single-center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mansoor J, Umair B. Primary pancreatic tuberculosis: a rare and elusive diagnosis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:226-228. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Iglesias García J, Ferreiro R, Lariño Noia J, Abdulkader I, Alvarez Del Castillo M, Cigarrán B, Forteza Vila J, Domínguez Muñoz JE. Pancreatic fusocellular sarcoma. The importance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in the differential diagnosis of solid pancreatic tumors. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Liu X, Li F, Xu J, Ma J, Duan X, Mao R, Chen M, Chen Z, Huang Y, Jiang J, Huang B, Ye Z. Deep learning model to differentiate Crohn's disease from intestinal tuberculosis using histopathological whole slide images from intestinal specimens. Virchows Arch. 2024;484:965-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |