Published online Jun 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i17.103920

Revised: January 4, 2025

Accepted: January 18, 2025

Published online: June 16, 2025

Processing time: 76 Days and 0.2 Hours

Clinical pathways (CPs) are structured guidelines introduced to improve health

To evaluate the clinical applicability and effectiveness of Korean medicine CPs for neck pain and shoulder pain in public healthcare institutions in South Korea.

We collected and analyzed data from patients aged 19 years and older who visited the outpatient clinic of the Department of Korean Medicine at the National Me

The CP completion rates were 93.3% for neck pain and 96.8% for shoulder pain. Patient satisfaction scores showed an improvement of 17.7% for neck pain and 18.0% for shoulder pain in the CP-implemented group compared to the non-CP group. For neck pain, significant improvements were observed in the numerical rating scale (NRS) and the neck disability index, while for shoulder pain, only the University of California-Los Angeles shoulder rating scale showed notable progress, with no substantial change in NRS scores.

This study partially confirms the clinical applicability and effectiveness of the Korean medicine CPs for neck pain and shoulder pain. Further research is required to enhance and validate these findings.

Core Tip: Clinical pathways (CPs) are standardized guidelines for medical interventions targeting specific diseases. This study evaluated the clinical applicability and effectiveness of Korean medicine CPs for neck and shoulder pain in South Korean public healthcare institution. Significant improvements were observed in the numerical rating scale and neck disability index for neck pain and in the University of California-Los Angeles shoulder rating scale for shoulder pain after CP implementation. Economic outcomes also showed notable improvements for shoulder pain. These results confirm the clinical applicability and effectiveness of Korean medicine CPs for treating neck and shoulder pain.

- Citation: Shin SJ, Kim JW, Jeong JC. Evaluation of clinical application of Korean medicine standard clinical pathway in a public hospital. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(17): 103920

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i17/103920.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i17.103920

Clinical pathways (CPs) are standardized and structured guidelines for medical interventions used in specific diseases[1]. It was adopted in the 1990s, primarily in the United States of America, to enhance the quality of medical services and promote medical efficiency by minimizing costs[2]. In South Korea, CP has been implemented in earnest since the late 1990s. According to data published in 2022, CP is mainly practiced for conditions covered by diagnosis-related groups, such as appendectomy, hernia surgery, tonsil and adenoid removal, etc.[3].

As CP in the Korean medicine system has only been developed since 2016, based on the 3rd Comprehensive Plan for the Development of Korean Medicine by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, most studies are either in the develop

Neck pain, characterized by tenderness or limited for pain and range of motion (ROM) in the neck region and radiating pain in the shoulder and upper extremities, is a common condition that affects approximately 67% of the population at least once in their lifetime[8]. Treatment for neck pain includes medication, physical therapy, exercise therapy, injection therapy, and surgery. Medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have side effects, including gastroin

Shoulder pain is characterized by pain and restricted ROM due to shoulder joint and surrounding soft tissue pathology[12]. It is considered the third most common musculoskeletal condition in primary care settings worldwide, after low back pain and knee pain. A 2022 survey reported a median prevalence of 16% (range 0.67%–55.2%) across countries[13]. Common treatments for shoulder pain include medication, physical therapy, injection therapy, exercise therapy, and surgery[14]. According to the 2022 Korean Medicine Yearbook, shoulder lesions (M75), a common cause of shoulder pain, ranked 9th, while dislocations, sprains, and strains of the joints and ligaments of the scapula (S43) ranked 10th among the 20 most frequent outpatient conditions treated in Korean medical institutions[15]. These findings highlight that shoulder pain is a prevalent condition in Korean medicine outpatient settings. Furthermore, with the recent increase in surgical procedures for shoulder disorders, the need for Korean medicine treatments for pain control and ROM recovery after surgery is increasing[16].

This study aimed to enhance the practical applicability of CPs and evaluate their clinical effectiveness by applying CPs for neck and shoulder pain developed for public medical institutions at the Korean Medicine Department of the National Medical Center (NMC). Initially, the developed CPs were optimized to fit the specific conditions of medical institutions to ensure smooth application. We aimed to explore the feasibility of applying the developed CP in an actual outpatient setting in a public hospital and to determine whether the CP application is effective in providing standardized care and improving patient satisfaction. This study was designed to compare the outcomes of CP-applying patients with those who did not receive CP to assess their contribution to standardized care, patient satisfaction, and identify areas for improvement.

This study was conducted with ethical considerations and the protection of patient rights was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NMC (NRC-2023-10-109).

The CP used in this study was optimized to fit the specific conditions of the Korean Medicine Department at NMC based on the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) developed by the Korea Institute of Korean Medicine[17,18].

The content of the CP consists of basic questionnaires regarding the patient's condition at the time of the visit and measured observations, such as medical examinations, differential diagnosis, evaluation, diagnostic tests, treatment, life guidance, and exercise education. In addition to the numerical rating scale (NRS)[19] for pain and ROM assessment, the neck disability index (NDI)[20] for neck pain and the University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) shoulder scale[21] for shoulder pain were used to assess the severity of the condition, and referral to other specialties or additional tests may be conducted if necessary. After diagnosis and evaluation, a combination of Korean medicine treatments such as acupunc

Inclusion criteria: Patients aged 19 years or older who visited the Korean Medicine Department in NMC from March 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023, were diagnosed and treated for shoulder and neck pain (Table 1).

| Disease | Korean standard classification of diseases |

| Neck pain | M25.68, M50.1, M50.8, M50.9, M54.2, S13.4, U30.3 |

| Shoulder pain | M13.91, M19.21, M19.81, M19.91, M24.21, M24.51, M24.61, M24.81, M24.91, M25.51, M25.61, M25.81, M25.91, M62.61, M75.0, M75.1, M75.2, M75.3, M75.4, M75.5, M75.8, M75.9, M79.11, M79.21, S40.0, S43.4, S43.5, S43.6, S43.7 |

Exclusion criteria: Patients below the age of 19 years.

Number of participants and rationale: A retrospective chart review was conducted without setting a target number of participants, and all patients who visited the hospital for selected conditions during the study period were included.

Data collection: Information on the study participants was collected. Personal information such as names, resident registration numbers, addresses, and phone numbers were not obtained to maintain confidentiality.

Study period: Data were collected from patients when the CP was not yet implemented (non-CP group) from March 1, 2023 to May 31, 2023 and from participants when the CP had been implemented (CP group) from June 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023.

Primary outcome variables: (1) Number of CP applications. The number of patients with the selected conditions who received CP was calculated; (2) CP application rate. The rate of CP applications was calculated by dividing the number of CP applications by the total number of patients with the condition and was expressed as a percentage; and (3) CP com

As secondary indicators, we examined clinical evaluation indicators, economic indicators, and medical service satisfaction. The average NRS scores at the initial and final visits were compared between the CP and non-CP groups. In the CP group, changes in moderate severity were assessed by comparing the average UCLA scale and NDI scores at the initial and final visits. Additionally, safety was evaluated by investigating the adverse reactions at each visit. The average number of visits and the total medical costs were compared between the CP and non-CP groups. Medical service satisfaction scores were compared between CP and non-CP groups. The satisfaction results were based on the results of a satisfaction questionnaire for each disease, which was conducted in 2023 as a patient satisfaction promotion activity of the Korean Medicine Department in the NMC after the initial consultation.

NRS score, visit days, and total medical expenses: To correct for selection bias, confounding variables such as gender, age, initial NRS score, and severity were adjusted before comparing the CP and non-CP groups. Here, severity refers to the presence of cervical disc herniation for neck pain and adhesive capsulitis for shoulder pain. Robust linear regression was used for the NRS and generalized linear regression with a logarithmic function as the link function was used for office visit days and total medical expenses.

NDI, UCLA scale: An independent t test or one-way repeated-measures analysis analysis of variance was used to assess significance.

Patient satisfaction: A 5-point likert scale was used to compare the average satisfaction scores between the CP and non-CP groups.

Neck pain: From March 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023, the number of patients diagnosed with neck pain who visited the Korean Medicine Department in NMC was 65. Of these 65 patients, 30 visited the department from June 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023, and were subjected to CP. The application rate was 46.2% (Table 2).

| Neck pain (non-applications) | Neck pain (applications) | Shoulder pain (non-applications) | Shoulder pain (applications) | |

| Age (years) (average) | 46.3 ± 12.3 | 50.1 ± 15.9 | 54.5 ± 12.8 | 50.3 ± 14.5 |

| Age (years) (minimum) | 26 | 27 | 30 | 22 |

| Age (years) (maximum) | 67 | 79 | 81 | 78 |

| Male | 13 (37.1) | 12 (40) | 16 (39.0) | 14 (45.2) |

| Female | 22 (62.9) | 18 (60) | 25 (61.0) | 17 (54.8) |

| Participants | 35 (53.8) | 30 (46.2) | 41 (56.9) | 31 (43.1) |

| Completed | 28 (93.3) | 30 (96.8) | ||

| Incomplete | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.2) |

Shoulder pain: The number of patients diagnosed with shoulder pain who visited the Korean Medicine Department in NMC from March 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023 was 72. Of these 72 participants, 31 visited the department from June 1, 2023 to August 31, 2023, and received CP. The application rate was 43.1% (Table 2).

Neck pain: A review of the medical records of the 30 patients with neck pain in the CP application group showed that 2 patients had missing NDI data in their follow-up charts, resulting in a completion rate of 93.3% (Table 2).

Shoulder pain: Reviewing the medical records of the 31 patients with shoulder pain in the CP group revealed that 1 patient had missing UCLA shoulder rating scale data in their follow-up chart, indicating a completion rate of 96.8% (Table 2).

Neck pain: Among the 35 patients in the non-CP group, there were 13 males (37.1%) and 22 females (62.9%). The average age was 46.3 years ± 12.3 years, with a minimum age of 26 years and a maximum age of 67 years. In the CP group including 30 patients, there were 12 males (40.0%) and 18 females (60.0%). The average age was 50.1 years ± 15.9 years, with a minimum age of 27 years and a maximum age of 79 years (Table 2).

Shoulder pain: In the non-CP group of 41 patients, there were 16 males (39.0%) and 25 females (61.0%). The average age was 54.5 years ± 12.8 years, ranging from 30 years to 81 years. Of the 31 patients in the CP group, there were 14 males (45.2%) and 17 females (54.8%). The minimum and maximum ages were 22 years and 78 years, respectively (Table 2).

Neck pain: Of the 35 patients without CP, 23 were diagnosed with M54.22 (cervicalgia, cervical region), 9 with S13.4 (sprain and strain of the cervical spine), 2 with M50.1 (cervical disc disorder with radiculopathy), and 1 with M54.20 (cervicalgia, multiple sites in spine).

Regarding the 30 patients with CP, 20 were diagnosed with M54.22 (cervicalgia, cervical region), 8 with S13.4 (sprain and strain of the cervical spine), 1 with M25.68 (stiffness of the joint, neuroendocrine carcinoma, other), and 1 with M50.9 (cervical disc disorder, unspecified) (Table 3).

| Neck pain | Shoulder pain | ||||

| KCD code | Non-applications (n = 35) | Applications (n = 30) | KCD code | Non-applications (n = 41) | Applications (n = 31) |

| M54.22 | 23 (65.7) | 20 (66.7) | M75.8 | 24 (58.5) | 12 (38.7) |

| S13.4 | 9 (25.7) | 8 (26.7) | M79.118 | 8 (19.5) | 10 (32.3) |

| M50.1 | 2 (5.7) | 0 | S43.4 | 4 (9.8) | 4 (12.9) |

| M54.20 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | M25.51 | 2 (4.9) | 0 |

| M25.68 | 0 | 1 (3.3) | M24.91 | 1 (2.4) | 0 |

| M50.9 | 0 | 1 (3.3) | M75.0 | 1 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) |

| M79.110 | 1 (2.4) | 0 | |||

| M62.61 | 0 | 3 (9.7) | |||

| M13.91 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | |||

Shoulder pain: Of the 41 patients without CP, 24 were diagnosed with M75.8 (other shoulder lesions), 8 with M79.118 (other myalgia, shoulder region), 4 with S43.4 (sprain and strain of the shoulder joint), and 2 with M25.51 (pain in the joint, shoulder region), one was diagnosed with M24.91 (joint derangement, unspecified, shoulder region), one with M75.0 (adhesive capsulitis of shoulder), and one with M79.110 (myofascial pain syndrome, shoulder region).

Of the total 31 patients in the CP group, 12 were diagnosed with M75.8 (other shoulder lesions), 10 with M79.118 (other myalgia, shoulder region), 4 with S43.4 (sprain and strain of shoulder joint), 3 with M62.61 (muscle strain, shoulder region), 1 with M13.91 (arthritis, unspecified, shoulder region), and 1 with M75.0 (adhesive capsulitis of shoulder) (Table 3).

Neck pain: Of the 30 patients in the CP application group, 19 patients had complete follow-up charts, and no adverse reactions were reported, indicating no adverse events from CP application.

Shoulder pain: Of the 31 patients in the CP application group, 22 patients had complete follow-up charts, and no adverse events were reported, indicating no adverse events from CP application.

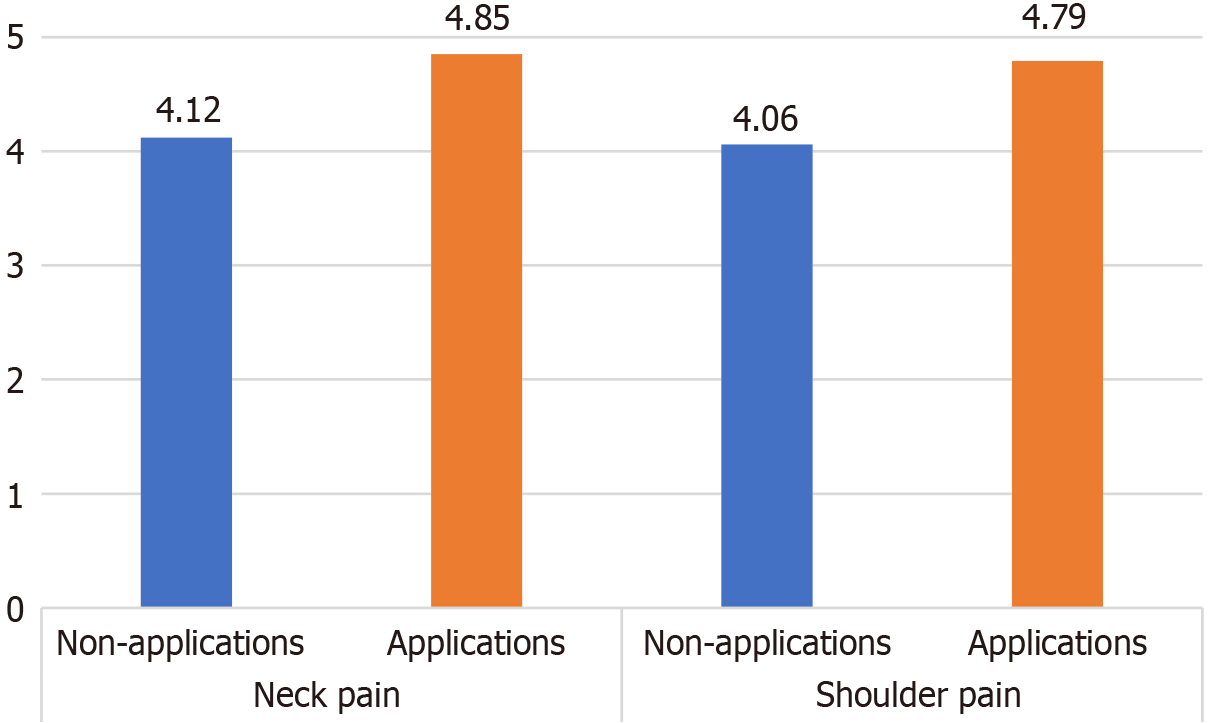

Neck pain: In the non-CP group, the average satisfaction score of the 30 respondents was 4.12, whereas the average score of the 30 respondents in the CP group was 4.85. Satisfaction score was 17.7% higher in the CP group than in the non-CP group (Figure 1).

Shoulder pain: In the non-CP group, the average satisfaction score of 30 respondents was 4.06, while the average score of 31 respondents in the CP group was 4.79. Satisfaction score was 18.0% higher in the CP group than in the non-CP group (Figure 1).

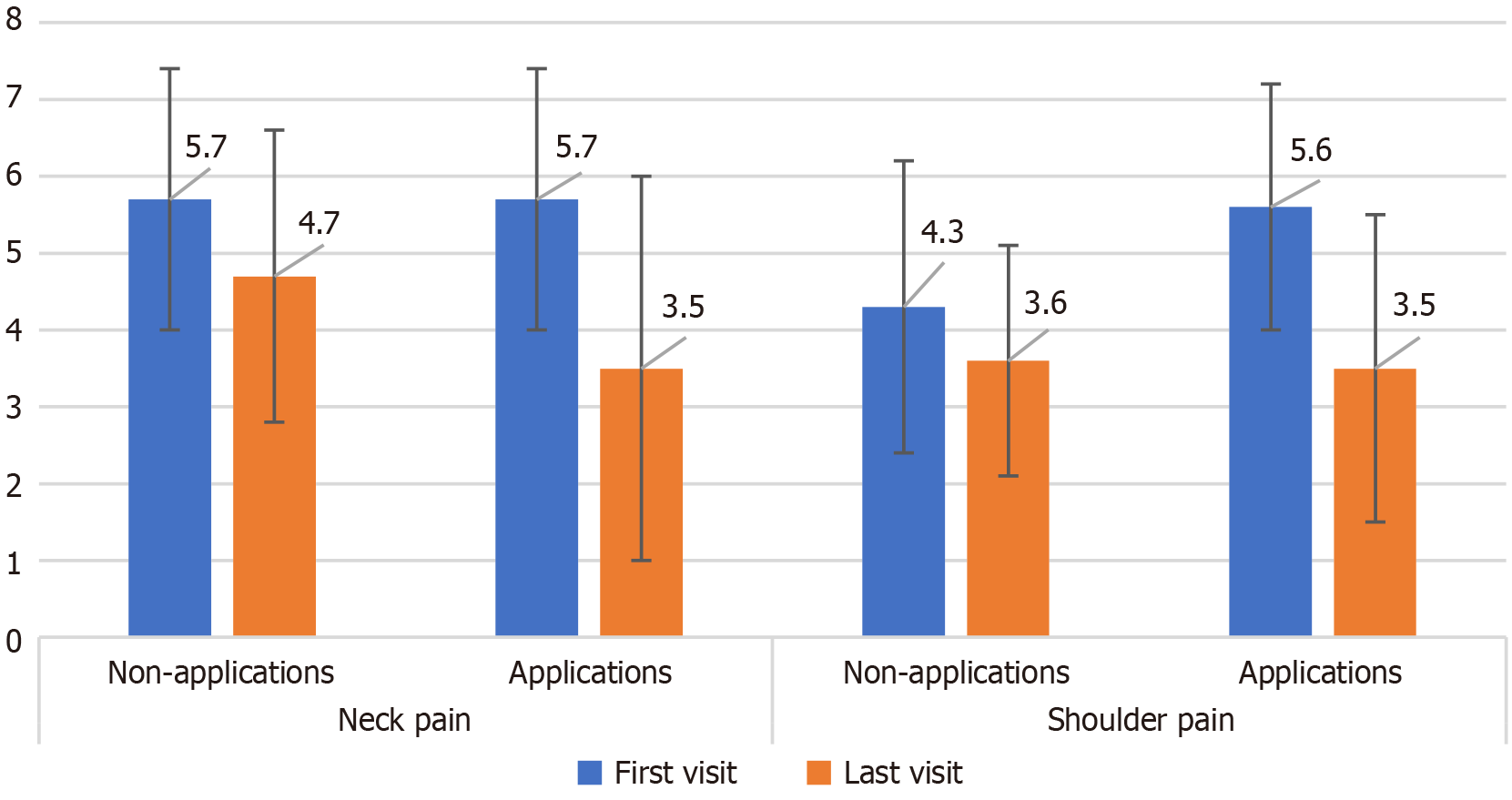

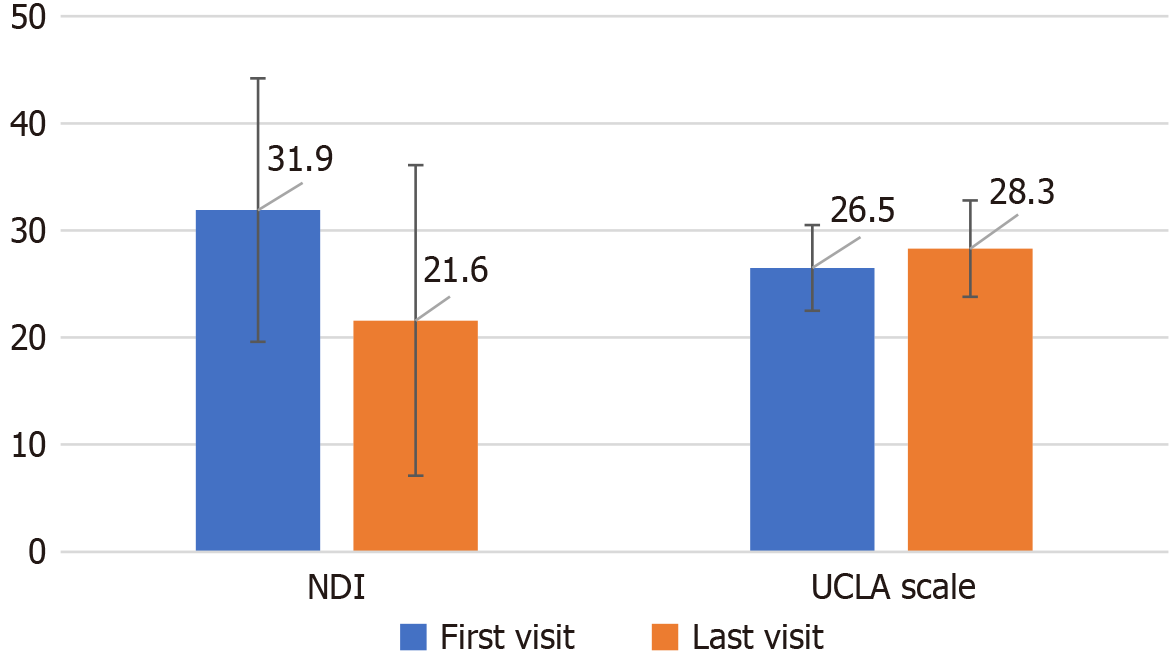

Neck pain: (1) NRS. Among the 35 patients in the non-CP group, 25 showed changes in NRS scores during the follow up. The average NRS decreased from 5.7 ± 1.7 at baseline to 4.7 ± 1.9 at the final visit. Of the 30 patients in the CP group, 19 experienced changes in NRS during the follow up. The average NRS decreased from 5.7 ± 1.7 at baseline to 3.5 ± 2.5 at the final visit. After adjusting for confounding variables, the decrease in NRS scores in the CP group was significantly greater than that in the non-CP group (P < 0.01) (Figure 2) (Table 4); and (2) NDI. Among the 30 patients in the CP group, 19 were followed up till the final visit. After excluding 2 patients with missing data, the NDI scores of the remaining 17 patients were analyzed. NDI scores improved from an average of 31.9 ± 12.3 at baseline to 21.6 ± 14.5 at the final visit, which was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Figure 3) (Table 5).

| Neck pain | Shoulder pain | |||||

| Number of visits | Total medical expenses | NRS change | Number of visits | Total medical expenses | NRS change | |

| Sex (reference male) | 0.05 ± 0.65 | 0.37 ± 0.32 | -0.79 ± 0.66 | -0.08 ± 0.33 | -0.14 ± 0.28 | 1.51 ± 0.48b |

| Age (years) (reference under 65) | 0.26 ± 0.30 | 0.16 ± 0.35 | 0.35 ± 0.93 | 0.01 ± 0.41 | -0.22 ± 0.41 | -0.70 ± 0.62 |

| Symptom intensity (NRS) | 0.01 ± 0.07 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | -0.33 ± 0.19 | 0.02 ± 0.08 | -0.04 ± 0.07 | -0.61 ± 0.14b |

| Severity | 0.17 ± 0.47 | 0.06 ± 0.53 | 1.45 ± 1.29 | 2.11 ± 0.45b | 1.16 ± 0.46b | 2.11 ± 1.21 |

| Groups | -0.30 ± 0.25 | -0.10 ± 0.27 | -1.74 ± 0.64b | -1.52 ± 0.45b | -0.61 ± 0.31 | -0.44 ± 0.49 |

| Intercept | 1.41 ± 0.65 | 11.25 ± 0.88c | 4.21 ± 1.86b | 1.48 ± 0.44b | 12.36 ± 0.36b | 0.97 ± 0.71 |

| Average | SD | SE of the mean | 95%CI of difference (lower limit) | 95%CI of difference (upper limit) | t test | Degree of Freedom | P value (double-tail) | |

| Neck disability index change | 10.30556 | 10.90307 | 2.56988 | 4.88358 | 15.72753 | 4.010 | 17 | 0.001 |

| University of California-Los Angeles change | -1.80952 | 3.32594 | 0.72578 | -3.32348 | -0.29557 | -2.493 | 20 | 0.022 |

Shoulder pain: (1) NRS. Among the 41 patients in the non-CP group, 23 showed changes in NRS during the follow-up period. The average NRS decreased from 4.3 ± 1.9 at baseline to 3.6 ± 1.5 at the final visit. Of the 31 patients in the CP group, 22 experienced changes in NRS scores during the follow up. The average NRS decreased from 5.6 ± 1.6 at baseline to 3.5 ± 2.0 at the final visit. After adjusting for confounding variables, the decrease in NRS score in the CP group was not statistically significant (Figure 2) (Table 5); and (2) UCLA shoulder rating scale. Of the 31 patients in the CP group, 22 were followed up till the last visit. After excluding 1 with missing data, the UCLA shoulder scale scores for the remaining 21 patients were analyzed. The average score improved from 26.5 ± 4.0 at baseline to 28.3 ± 4.5 at the final visit, and the increase was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Figure 3) (Table 5).

Neck pain: (1) Number of visits. The average number of hospital visits in the CP and non-CP groups were 2.7 days ± 2.1 days and 3.7 days ± 3.3 days, respectively. After adjusting for confounding variables, the decrease in the number of visits was not statistically significant in the CP group (Table 4); and (2) Total medical expenses. The mean total medical ex

Shoulder pain: (1) Number of visit days. The average number of hospital visits in the CP and non-CP groups were 2.9 days ± 3.7 days and 5.0 days ± 7.4 days, respectively. After adjusting for confounding variables, the decrease in the number of visit days in the CP group was statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Table 4); and (2) Total medical expenses. The mean total medical expenses for patients with shoulder pain in the CP and non-CP groups were KRW 115827 ± KRW 130013 and KRW 175552 ± KRW 191904, respectively. After adjusting for confounding variables, the reduction in the total medical expenses in the CP group was statistically significant (P < 0.1) (Table 4).

The World Health Organization defines traditional medicine as a comprehensive system of knowledge, skills, and practices used in the prevention and treatment of diseases based on indigenous theories, beliefs, and experiences of various cultures. It is recognized as a health resource with many applications, particularly in the prevention and ma

In China, a study conducted a quality assessment of 27 traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) CPs using the integrated care pathway appraisal tool, an assessment tool developed by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom[26], and compared the cost of hospitalization after applying TCM CPs to patients admitted for stroke with standard medical care, length of admission, and postoperative complications compared to standard care[27]. Another study assessed the impact of an integrated CP combining TCM and Western medicine for the management of chronic heart failure, focusing on readmission rates and quality of life[28]. There is a need for further research in Korea, as there has been no case of developing a CP utilizing traditional medicine or evaluating its applicability and effectiveness.

According to a survey on the use of Korean medicine published by the National Institute for Korean Medicine Development in 2023, the main purpose of Korean people using Korean medicine is to treat musculoskeletal disorders (74.8%), of which neck and shoulder treatments were the second and third most common among the top five categories, respectively. To retrospectively evaluate the utilization and effectiveness of a CP developed to standardize and improve the quality of management with Korean medicine, it was deemed appropriate to focus on frequently occurring condi

Indicators, such as application rates, completion rates, and length of hospital stay, are commonly used to assess the effectiveness of CP for inpatient care[3]. However, no previous studies have evaluated the use and effectiveness of CPs in outpatient settings using Korean medicine; thus, leading to challenges in determining the indicators to use. This study aimed to establish a standardized Korean medicine treatment system, improve the quality of Korean medical services, enhance patient satisfaction, and optimize medical costs. An expert consultation was conducted to determine the appropriateness of using CP application cases, CP application rates, and CP completion rates as primary outcome variables. Three researchers with PhDs in Korean medicine and one statistician with experience in CP research were consulted individually in writing or meetings.

It was agreed following the consultation that the number of CP applications, CP application rate, and CP completion rate were appropriate for the study as primary evaluation indicators. However, unlike inpatient studies, in which CP is considered complete if it is maintained until discharge, there is no clear standard for CP completion in outpatient settings. Additional consultations and discussions led to the definition of CP completion as the performance of standardized treatment according to the planned protocol.

The purpose of CP performed in the outpatient setting in this study was not different from the goals of improving the quality of care and promoting medical efficiency[1] which are achieved through inpatient CP. The completion of treatment according to the management plan and discharge after applying CP in the inpatient setting is considered complete. Similarly, it is acceptable to set the standard of completion based on whether the treatment set in the CP was performed according to the protocol in the outpatient setting. Therefore, in this study, completion was defined as whether the initial and return charts were fully filled out, and standardized treatment was performed as scheduled. Unlike inpatient settings, outpatient settings may experience follow-up dropout. Thus, if the treatment ended after one visit, completion was restricted to the initial chart documentation.

A satisfaction survey was used as a secondary outcome variable and was not set as a requirement for CP completion. This decision was based on the potential loss of anonymity if satisfaction survey results were included in mandatory medical records, according to South Korea's Statistics Act, Article 33. Patient satisfaction data were collected separately using data from the NMC QI activities. Survey data were collected during the initial visit, as determined by the expert consultations and meetings.

Clinical indicators of patient post-treatment status were collected and analyzed as secondary outcome variables. To chart CPs at the institution, it was necessary to record the NRS and physical examinations at every visit. The clinical indicators collected as secondary outcomes were compared between the initial and final visits before and after the analysis.

The analysis showed that CP application rates were 43.1% and 46.2% for neck and shoulder pain, respectively. These figures are similar to the average inpatient CP application rate of 50% in 32 regional public hospitals in South Korea as of April 2024[26]. In a previous retrospective analysis separating the non-CP and CP groups into the same 3-month period, the coverage rate did not exceed 50%. This is likely due to the fact that patients who visited the hospital from March 1, 2023 to May 31, 2023 were treated as patients in the non-CP group and then visited the hospital after June 1, 2023 as the same patient maintained in the non-CP group rather than the CP group.

CP completion rates were 93.3% and 96.8% for neck and shoulder pain, respectively, similar to the average completion rate of 96.8% for inpatient CPs in 32 regional public hospitals in South Korea as of April 2024[29]. Regarding CP to be completed, the initial and revisit charts must be complete, and in this study involving musculoskeletal conditions, chart items included NRS, ROM, physical examination, and questionnaire completion in addition to basic questionnaires. The high completion rate despite the additional requirements may be attributed to the fact that the required physical examination was selected as a frequently used item in case reports in Korean medicine over the past decade[30-32], and the process was set up to allow the questionnaire to be completed while waiting for an appointment, to minimize practice resource commitment.

Furthermore, CP completion included whether the set prescriptions were performed correctly. In this study, the set prescriptions were selected based on the recommendation grades presented in the CPG and by considering prescriptions that are frequently used by the Korean Medicine Department of NMC. The basic set consisted of acupoint acupuncture (2 or more points), intervertebral acupuncture (intra-articular acupuncture for shoulder pain), and transdermal infrared therapy, and an additional set consisting of a combination of moxibustion, electrical acupuncture, and simple chuna in addition to the basic set, based on the patient’s diagnosis. Optional prescriptions were limited to differentiation tech

Compared to the non-CP group, satisfaction with medical services improved by 17.7% and 18.0% in the CP group for neck and shoulder pain, respectively. A nationwide study of factors affecting satisfaction with outpatient medical services in South Korea found that treatment outcomes, sufficient communication about disease management, anxiety, empathy, and courteous treatment were associated with high overall satisfaction[33]. It is possible that patient-friendly factors such as prognosis explanation, exercise education, and lifestyle guidance were enhanced in the CP group compared to those of the non-CP group, which may have contributed to improve satisfaction.

However, improvements in clinical and economic indicators due to the application of CP have been inconsistent. These findings are similar for inpatient CP. For example, a systematic review of 11 studies on stroke CP demonstrated that CP implementation improved treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction compared to standard care[34]. However, a meta-analysis of 11 studies in which CP was utilized in the treatment reported a positive impact of CP on reducing economic indicators such as length of hospital stay, but there was no significant difference regarding standard care for clinical indicators such as levels of quality of life and satisfaction[35]. These results may be due to various biases in the analysis process, and it is recommended that further studies be conducted using Korean medicine to confirm the efficacy of CP after adjusting for confounding variables such as gender, age, and severity.

This study explores the applicability and improvement of CP developed for public healthcare organizations. The significance of this study is that CP was applied in an outpatient setting rather than during hospitalization. Unlike existing studies on CP in Korean medicine that were conducted on a small number of patients, this study was conducted with a relatively large number of participants. In addition, this study showed that high patient satisfaction was obtained through a more standardized treatment, which was confirmed through a retrospective analysis.

However, the limitations of the study include the use of a quantitative questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction and discomfort with CP, and the lack of further analysis of those who return and did not return to the hospital in the CP and non-CP groups. Further research is required to explore the qualitative aspects of this study through in-depth interviews with patients and healthcare providers.

This study evaluated the clinical applicability and effectiveness of CP for neck and shoulder pain. The CP completion rate was 93.3% for neck pain and 96.8% for shoulder pain, confirming the clinical applicability of CP. Satisfaction scores were 17.7% higher for neck pain and 18.0% higher for shoulder pain in the CP group compared to the non-CP group. For neck pain, significant improvements were observed in the NRS scores and NDI, while for shoulder pain, only the UCLA shoulder rating scale showed significant improvement and there was no significant change in the NRS scores. This confirms the partial clinical effectiveness of CP. Further studies are needed to improve and validate these results.

| 1. | Dy SM, Garg P, Nyberg D, Dawson PB, Pronovost PJ, Morlock L, Rubin H, Wu AW. Critical pathway effectiveness: assessing the impact of patient, hospital care, and pathway characteristics using qualitative comparative analysis. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:499-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aspland E, Gartner D, Harper P. Clinical pathway modelling: a literature review. Health Syst (Basingstoke). 2019;10:1-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Oh I, Chang T, Kim H, Han J, Lee C. Status of the Development and Utilization of Critical Pathways in Medical Institutions in South Korea. Qual Improv Health Care. 2022;28:2-13. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Park H, Kim H, Park S, Heo I, Hwang M, Shin B, Hwang E. A Prospective Case Series Protocol for Clinical Pathway of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J Korean Med Rehabil. 2022;32:73-82. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Kim Y, Kim D, Park J, Jin Y, Hwang S. A survey on doctor of Korean Medicine’s recognition for developing Korean medicine clinical practice guideline of Sanhupung. J Orient Obstet Gynecol. 2022;35:1-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Kim J, Chae SY, Ko M, Jo M, Jang J, Kim JY, Kim H, Park KJ, Hwang J, Goo B, Park Y, Baek Y, Nam S, Seo B. A Study on the Development and Application of Korean Medical Critical Pathway of Lumbar Disc Herniation in Four Different Medical Associations. J Korean Med. 2021;42:1-8. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Eom Y, Kwon D, Kim Y, Lee H, Chung S, Cho S. A pilot study on effects of critical pathway application for Hwa-Byung. J of Oriental Neuropsychiatry. 2021;32:337-343. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, Sullman MJM, Kolahi AA, Safiri S. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 88.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bindu S, Mazumder S, Bandyopadhyay U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;180:114147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 891] [Article Influence: 178.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | HIRA Bigdata Open portal. Available from: https://opendata.hira.or.kr/home.do. |

| 11. | Neck pain Clinical Practice Guideline of Korean Medicine. Internet. Available from: https://nikom.or.kr/nckm/module/practiceGuide/view.do?guide_idx=148&menu_idx=14. |

| 12. | Murphy RJ, Carr AJ. Shoulder pain. BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010:1107. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lucas J, van Doorn P, Hegedus E, Lewis J, van der Windt D. A systematic review of the global prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Greenberg DL. Evaluation and treatment of shoulder pain. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:487-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | National Institute for Korean Medicine Development. Available from: https://nikom.or.kr/. |

| 16. | Shoulder pain clinical practice guideline of Korean medicine. Available from: https://nikom.or.kr/nckm/module/practiceGuide/viewPDF.do?guide_idx=141. |

| 19. | Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Fainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S; European Palliative Care Research Collaborative (EPCRC). Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1913] [Cited by in RCA: 1735] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Howell ER. The association between neck pain, the Neck Disability Index and cervical ranges of motion: a narrative review. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2011;55:211-221. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Roddey TS, Olson SL, Cook KF, Gartsman GM, Hanten W. Comparison of the University of California-Los Angeles Shoulder Scale and the Simple Shoulder Test with the shoulder pain and disability index: single-administration reliability and validity. Phys Ther. 2000;80:759-768. [PubMed] |

| 22. | WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978924151536. |

| 23. | de Valois B, Asprey A, Young T. "The Monkey on Your Shoulder": A Qualitative Study of Lymphoedema Patients' Attitudes to and Experiences of Acupuncture and Moxibustion. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:4298420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, Irnich D, Witt CM, Linde K; Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration. Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Pain. 2018;19:455-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Takakura N, Takayama M, Kawase A, Kaptchuk TJ, Kong J, Vangel M, Yajima H. Acupuncture for Japanese Katakori (Chronic Neck Pain): A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double-Blind Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:2141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ling J, Pan Y, Yao L, Chen Y, Liu G, Yang K. The methodological quality of the traditional Chinese medicine clinical pathway in China. Cochrane Colloquium Abstracts. 2017. |

| 27. | Wang B, Chen D, Zhou H, Shi H, Xie Q. Influence of clinical pathways used the hospitals of Traditional Chinese Medicine on patients hospitalized with stroke: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pan G, Ji W, Wang X, Li S, Zheng C, Lyu W, Feng X, Xia Y, Xiong Z, Shan H, Yang H, Zou X. Effects of multifaceted optimization management for chronic heart failure: a multicentre, randomized controlled study. ESC Heart Fail. 2023;10:133-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Public health CP monitoring system. Available from: https://www.pubcp.or.kr/introduce/intro.do. |

| 30. | Song K, Seo J, Song S. Cho M, Choi B, Ryu W, Kim D, Jeon W. A case report on the improvement of range of motion and pain relief for patients diagnosed with supraspinatus tendinosis, subacromial bursitis and subdeltoid bursitis treated with megadose Shinbaro pharmacopuncture. J Haeh Med. 2017;26:73-80. |

| 31. | Ryu G, Ju A, Park M, Choo W, Choi Y, Moon Y, Choi H. Patients Treated with Acupuncture on Splenius Muscle and Combined Korean Medicine for Acute Dizziness Caused by Whiplash Injury: Three Case Reports. J Int Korean Med. 2020;41:1210-1222. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Hong M, Kim J, Park M, Yoon Y, Kim S, Kim N. A Case Report on Ossification of Posterior Longitudinal Ligament Treated by Korean Medicine: Focusing on Chuna Therapy. Korean Soc Chuna Man Medicine Spine Nerves. 2020;15:135-145. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Kim J, Park Y. Outpatient Health Care Satisfaction and Influential Factors by Medical Service Experience. KJ-HSM. 2020;14:15-30. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Nizar TE, Nurwahyuni A, Candi C. Systematic Review: The Influence of Clinical Pathway Implementation on Length of Stay and Patient Outcome of Stroke Infarct Patients. Proceedings of the International Conference of Health Development. Covid-19 and the Role of Healthcare Workers in the Industrial Era (ICHD 2020). 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Trimarchi L, Caruso R, Magon G, Odone A, Arrigoni C. Clinical pathways and patient-related outcomes in hospital-based settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:e2021093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |