Published online May 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i15.98608

Revised: November 27, 2024

Accepted: January 2, 2025

Published online: May 26, 2025

Processing time: 204 Days and 14.7 Hours

Abdominal cocoons (ACs) lack characteristic clinical manifestations and are main

Here, we report a 16-year-old female patient with intestinal obstruction due to AC. She was treated with abdominal surgery three times. First, she underwent a laparotomy for peritonitis after trauma from a traffic accident. During the pro

Currently, abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography is the best imaging modality for pre

Core Tip: This work reported a case of ostomy occlusion due to abdominal cocoons after post-traumatic ileostomy. The patient underwent three consecutive abdominal surgeries and had a complex condition. In our hospital, she was treated scientifically and underwent two consecutive abdominal surgeries. In the end, she was successfully discharged from the hospital and is now recovering well. This rare case is important to summarize for the medical community. Combined with a literature review, the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and treatment strategies of abdominal cocoons were summarized.

- Citation: Xu R, Sun LX, Chen Y, Ding C, Zhang M, Chen TF, Kong LY. Stoma occlusion caused by abdominal cocoon after abdominal abscess surgery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(15): 98608

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i15/98608.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i15.98608

Abdominal cocoons (AC) are a rare abdominal disease that is characterized by partial or total abdominal organs being wrapped or covered by a layer of fibrous membrane-like material, resembling a cocoon, resulting in a chronic or acute disease[1]. It was first described as fibrous peritonitis in 1907[2], and abdominal cocoon was first reported and named by Foo et al[3]. The age of onset of AC is wide, and the incidence in males is twice that of females[4,5]. The clinical symptoms are mostly nonspecific, often due to intestinal obstruction or abdominal mass.

AC is clinically divided into idiopathic and secondary according to the etiology. Studies have found that idiopathic AC cases are generally distributed in tropical or subtropical regions. It is hypothesized that the pathogenesis of idiopathic AC patients is closely related to congenital peritoneal or vascular dysplasia. Secondary AC is related to the stimulation of anticancer drugs, chronic peritoneal dialysis, tuberculous peritonitis, autoimmune diseases, and other factors[6]. All these factors can lead to the inflammatory reaction of the peritoneum, resulting in the reduction of mesothelial cells, the con

There is a lack of characteristic clinical manifestations, and it is difficult to distinguish it from intestinal obstruction caused by other reasons, resulting in difficulties in preoperative diagnosis and easy misdiagnosis and mistreatment. Therefore, we reported a 16-year-old female who presented with a difficult case of AC. We retrospectively analyzed the clinical and imaging manifestations of this case of AC and summarized the experience of diagnosis and treatment in order to improve the level of preoperative diagnosis and surgical treatment of AC.

A 16-year-old female presented to our hospital with abdominal pain and distension with no flatus and defecation from the stoma for 7 days.

The patient underwent ileostomy + drainage of pelvic abscess for abdominal abscess 2 years ago in another hospital, and intestinal torsion reduction + intestinal decompression 1 year ago in our hospital. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy + ileostomy in another hospital 1 year ago due to closed abdominal injury. Two weeks prior to presentation, she underwent exploratory laparotomy + enterolysis in our hospital due to stoma occlusion.

There were no other past illnesses to report.

The patient declared that she had no family history of genetic diseases.

The results were as follows: Temperature 38.2 °C; pulse 120 beats/min; respiration 23/min; and blood pressure 90/55 mmHg. The patient presented with a clear spirit, poor mental status, abdominal distension, small intestinal stoma in the left abdomen, no obvious flatus and fluid passing, total abdominal tenderness, total abdominal muscle tension, rebound pain, and weak bowel sounds.

WBC was 7.3 × 109/L, neutrophil was 79.8%, and hemoglobin was 10.1 g/dL.

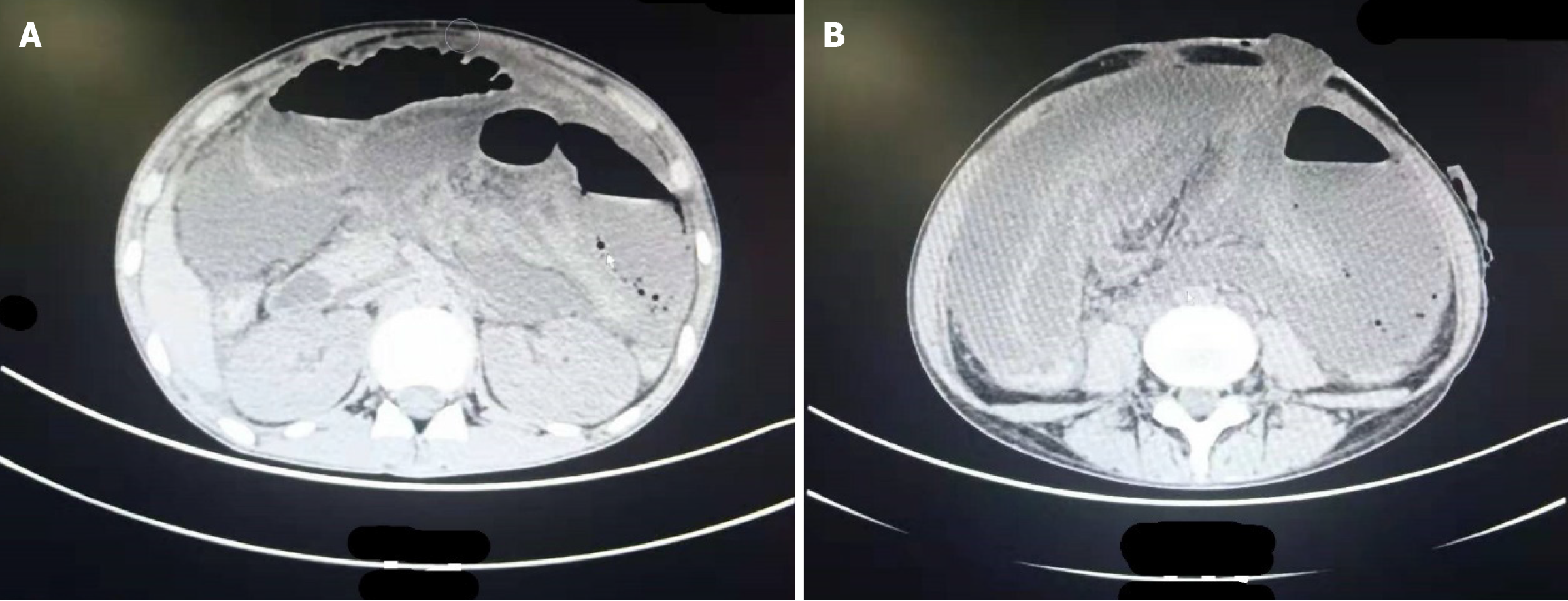

Abdominal CT: Massive encapsulation of fluid and pneumatosis were found in the abdominal cavity, with a slightly thicker wall and a wide gas-fluid level. In addition, it was not clearly demarcated from the adjacent small intestine in the left upper abdomen and could not be ruled out as being connected with the intestinal canal. There was effusion in the abdominopelvic cavity, a small amount of free gas, and a swollen intestinal wall at the left lower abdominal stoma (Figure 1).

Dr. and Pro. Chuang Ding (Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, China), Rui-Mei Zhong (Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, China), and Bin Lin (Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, The Affiliated Suqian Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, China) participated in the consultation. Exploratory laparotomy was recommended for confirmation of diagnosis and treatment.

The final diagnosis of AC was made in conjunction with the patient’s medical history and intraoperative conditions.

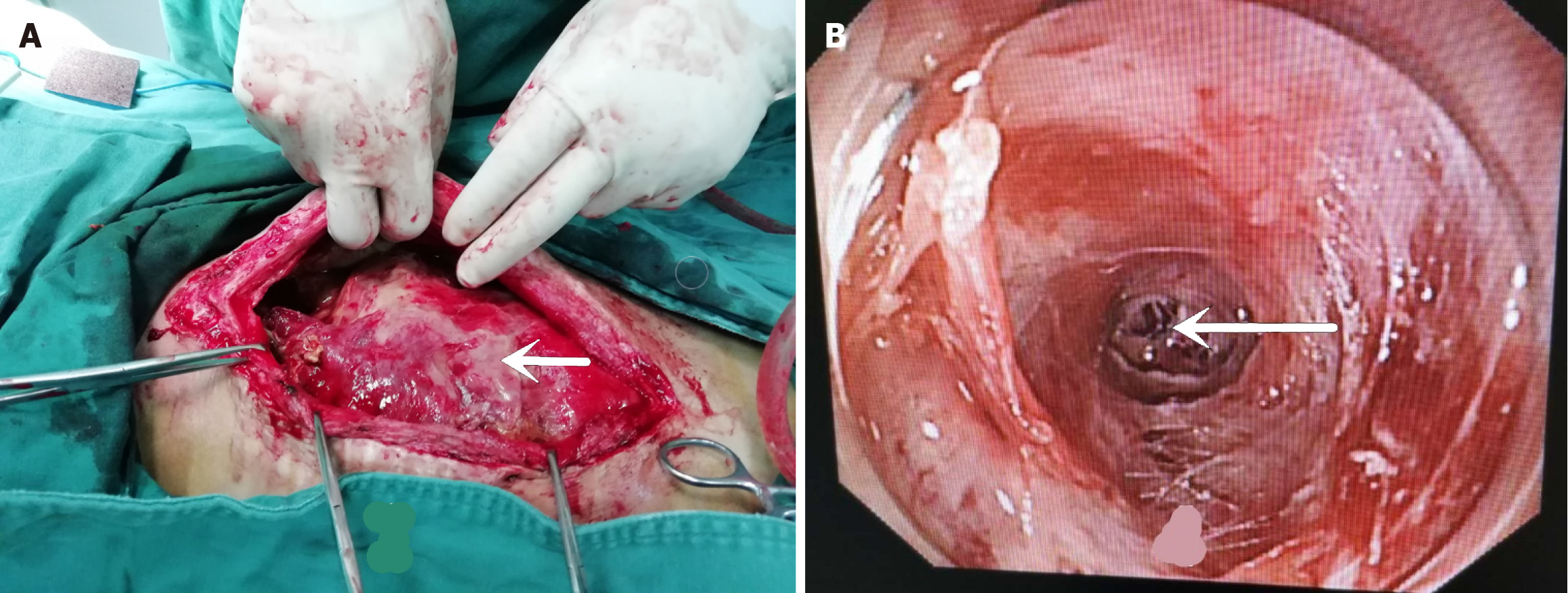

Emergency exploratory laparotomy: A large amount of yellow turbid pus was seen in the abdominal cavity with a foul odor and significant edema of organs. It was difficult to determine the normal intestinal canal alignment, and pie-like organ adhesions were observed (Figure 2A). Abdominal adhesion release + abscess incision drainage and tube placement were performed in a difficult situation. Flatus and fluid passing started from the stoma 5 days postoperatively, and the patient was gradually put on a liquid diet.

At 20 days postoperatively, the stoma stopped flatus and fluid passing again, and the patient had obvious abdominal distension and pain. After consultation with the gastroenterology department, it was decided to perform enteroscopy through the stoma. Two channels were seen at the stoma. One was smoothly accessed, and occlusion at the distal end of the small intestinal stoma was considered. The other was inserted about 10 cm, and a blind end with no slit was seen, which was difficult for the enteroscope to pass through. Occlusion in the proximal small intestine was thus considered (Figure 2B). Considering the extremely high risk of percutaneous puncture, puncture decompression was not recommen

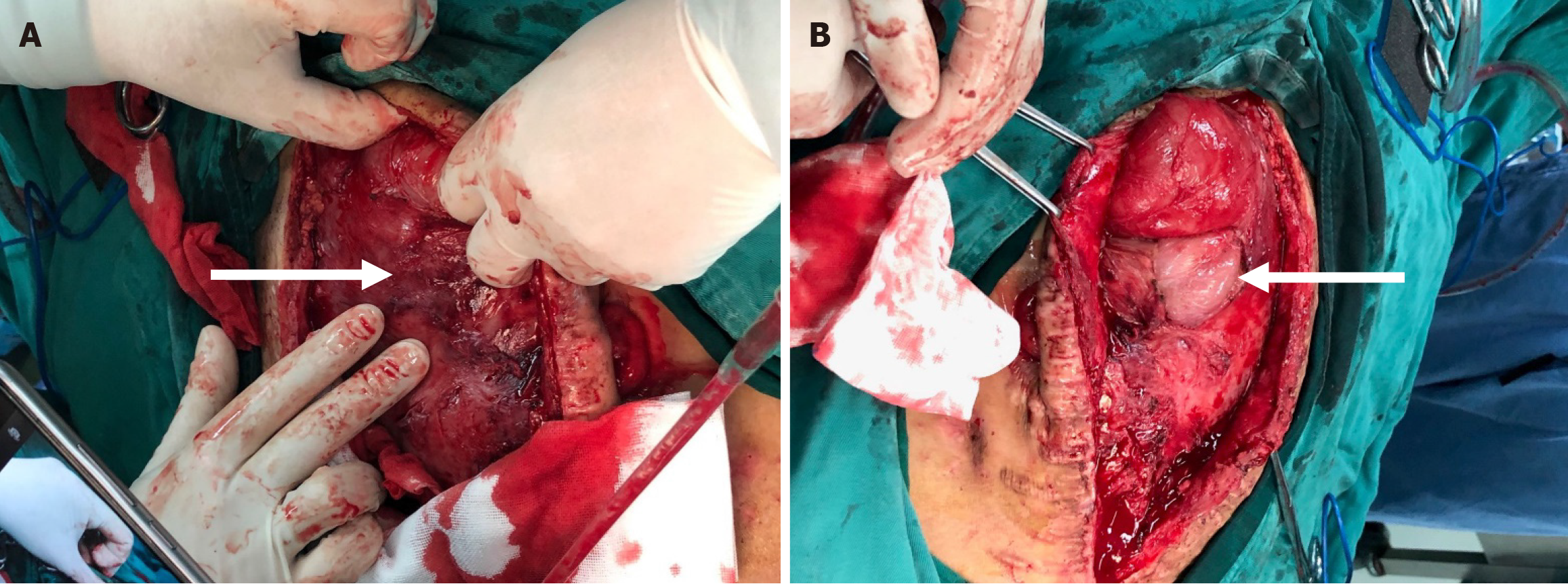

After another 20 days of conservative treatment, the intestinal obstruction progressively worsened, and the patient had no choice but to undergo emergency surgery again. Intraoperatively, the surface of all organs in the abdominal cavity was covered with dense fibrous tissue (Figure 3A), which was dark red, with varying thickness (up to 2.0 cm). In particular, due to the extensive adhesion between the intestinal canal and the abdominal wall and between the intestinal canals, it was impossible to identify the normal intestinal canal shape. After the fibrous tissue was separated from the abdominal wall, the white dilated small intestine was exposed (Figure 3B), and obvious edema was seen (maximum width of 10 cm). The small intestinal canals had roughly normal color, no necrosis, and disordered alignment, and the adhesions could still be separated. It was found that the stoma was 3 cm away from the Treitz ligament, and the dilation of the small intestine was the most obvious in the proximal end of the stoma. By exploration of the proximal stoma, occlusion approximately 15 cm away from the stoma was found. Decompression of the small intestine after stoma resection was performed, with about 2500 mL of yellow-green intestinal fluid harvested. Separation was continued, and the distal ileum and colon and rectum became patent. After stoma resection, the proximal fistulation and distal closure were performed.

Postoperatively, the patient underwent gastrointestinal decompression, anti-inflammatory treatment, and nutritional support. The stoma started flatus passing at 3 days postoperatively and fluid passing smoothly at 4 days postoperatively. The patient drank water at 5 days postoperatively and had a liquid diet at 7 days postoperatively. The drainage tube was withdrawn gradually at 9 days postoperatively. The stitches were removed, and the patient was discharged at 2 weeks postoperatively. At the 6-month postoperative follow-up, the patient had recovered well without fever, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, or stoppage of flatus and fluid passing from the stoma.

Herein, the patient had a history of three abdominal surgeries and suffered severe abdominal adhesions as could be seen from the intraoperative findings. One week before presentation, the patient had abdominal pain symptoms following electronic enteroscopy in another hospital. Although no gastrointestinal contents were seen in the abdominal cavity during the surgical exploration, the possibility of intestinal perforation due to enteroscopy was not ruled out based on the abdominal computed tomography (CT) and surgical exploration. It can be seen that post-trauma intestinal injury, history of multiple surgeries, post-enteroscopy intestinal injury, and abdominal abscess formation were the common causes of AC in this patient.

The diagnosis of AC is difficult. Wei et al[8]reported a preoperative diagnosis rate of only 16.67% in 24 patients with AC. Although abdominal enhanced CT is the best imaging method for preoperative evaluation of AC[9], the majority of patients are diagnosed by intraoperative exploration. The intraoperative findings of the patient herein were extremely typical. The surface of all organs in the abdominal cavity was covered with dense fibrous tissue, with varying thickness (up to 2.0 cm). The pelvic and lateral abdominal walls were thicker, which is caused by the accumulation of abdominal pus or exudate at a lower position and the formation of cellulose (Figure 3A). On the contrary, when the cocoon-like membranoid substance was peeled off, the intestinal tissue underneath had clearer boundaries, and the adhesions between intestinal canals were not dense (Figure 3B), which may be related to the prolonged chronic dilatation of the intestinal canal, absorption of cellulose between intestinal canals, and separation of fibrous adhesions after the dilatation of intestinal canals.

When all organs are covered by cocoon-like membranous tissue during intraoperative exploration, the surgeon may struggle to formulate a plan. Finding the breakthrough of dissection is the key to the success of surgery. Because of the thin coverage of the fibrous membrane in the upper abdominal cavity, coupled with the massive gastric contraction and relaxation, bluntly peeling off the membranous tissue through the side of greater curvature and the inferior pole of the spleen could be used as a surgical approach. This could simplify complex surgery and reduce the secondary damage by surgery.

After the formation, AC is often detected clinically due to the development of obstructive symptoms. Uzunoglu et al[10] once reported a case of recurrent obstruction caused by AC in a 16-year-old female, but the patient had no history of abdominal trauma in this report. The case herein was characterized by a history of multiple surgeries and a small intes

In combination with intraoperative findings, dense cellulose was considered to be elastic to a certain degree, which may explain the failure of obstruction relief by various conservative treatments, such as dilation of stoma, enema, dila

No precise criteria are available for the time interval between two surgeries for AC and the assessment of surgical risk. Before the second surgery, the authors were concerned about the severe abdominal adhesions intraoperatively, which would cause excessive trauma if massive resection of the small intestine had to be performed. The patient herein underwent two successful surgeries within an interval of 40 days, and no intraoperative intestinal injury was caused. Therefore, a 40-day interval between two surgeries may be relatively safe. However, the authors speculate that the extensive dilatation of the small intestine, which spontaneously separates the adhesions in the intestinal space, is the key to the successful total excision of cellulose membranes at such a short interval. Future research should focus on systematic treatment of AC and minimization of trauma and mortality of patients. Early anal dilatation, dilatation of the stoma, and adequate postoperative abdominal drainage are key factors in preventing the formation of AC. This case provides references for clinicians to understand AC to prevent and treat the disease effectively.

Thank you to everyone who has contributed to the care of this special patient and the writing of this article.

| 1. | Sharma D, Nair RP, Dani T, Shetty P. Abdominal cocoon-A rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:955-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fei X, Yang HR, Yu PF, Sheng HB, Gu GL. Idiopathic abdominal cocoon syndrome with unilateral abdominal cryptorchidism and greater omentum hypoplasia in a young case of small bowel obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4958-4962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akbulut S. Accurate definition and management of idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:675-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Dave A, McMahon J, Zahid A. Congenital peritoneal encapsulation: A review and novel classification system. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2294-2307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Tannoury JN, Abboud BN. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: abdominal cocoon. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1999-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Singhal M, Krishna S, Lal A, Narayanasamy S, Bal A, Yadav TD, Kochhar R, Sinha SK, Khandelwal N, Sheikh AM. Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis: The Abdominal Cocoon. Radiographics. 2019;39:62-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wei B, Wei HB, Guo WP, Zheng ZH, Huang Y, Hu BG, Huang JL. Diagnosis and treatment of abdominal cocoon: a report of 24 cases. Am J Surg. 2009;198:348-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aziz W, Malik Y, Haseeb S, Mirza RT, Aamer S. Abdominal Cocoon Syndrome: A Laparoscopic Approach. Cureus. 2021;13:e16787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Uzunoglu Y, Altintoprak F, Yalkin O, Gunduz Y, Cakmak G, Ozkan OV, Celebi F. Rare etiology of mechanical intestinal obstruction: Abdominal cocoon syndrome. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:728-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kawanishi H, Kawaguchi Y, Fukui H, Hara S, Imada A, Kubo H, Kin M, Nakamoto M, Ohira S, Shoji T. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in Japan: a prospective, controlled, multicenter study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:729-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chorti A, Panidis S, Konstantinidis D, Cheva A, Papavramidis T, Michalopoulos A, Paramythiotis D. Abdominal cocoon syndrome: Rare cause of intestinal obstruction-Case report and systematic review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e29837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |