Published online May 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i14.101950

Revised: December 7, 2024

Accepted: January 2, 2025

Published online: May 16, 2025

Processing time: 104 Days and 15.4 Hours

Intraosseous lipoma of bone is one of the rarest benign bone tumors, which often involves the metaphysis of long tubular bones, especially the femur, tibia, fibula, and calcaneus. Bone lipoma can be characterized by chronic dull pain but can also be asymptomatic most of the time. As a result, it is less likely to attract people’s attention and is occasionally diagnosed through imaging examination during routine physical health check-up.

We describe a clinical case of intraosseous lipoma in a 21-year-old patient with chronic pain in the left lower limb for four years without any significant physical findings apart from the minimal swelling and local tenderness over the median ankle. Computerized tomography suggested the possibility of a lipoma on the left distal tibia, but the pathological examination could make a definite diagnosis. The intraosseous lipoma of the left distal tibia was treated by surgical curettage, bone graft, and internal fixation with steel plate, since the conservative treatment is often ineffective. Postoperatively, the patient made an uneventful recovery and was able to do daily activities without any restrictions. In addition, local recur

Bone lipoma is very rare and often exhibits no characteristic clinical manifestation. The confirmative diagnosis of lipoma largely relies on a combination of imageo

Core Tip: Bone lipoma is very rare and often exhibits no characteristic clinical manifestation. The confirmative diagnosis of lipoma largely relies on a combination of imageology and biopsy. Surgical intervention is a recommended conventional therapy for bone lipoma. In the present case, the patient made an uneventful postoperative recovery with a good prognosis, and no local recurrence of the tumor was observed.

- Citation: Liu P, Zhang K, Zeng JK, Chang YF, Zhuang KP, Zhou SH. Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic study of intraosseous lipoma of the tibia: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(14): 101950

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i14/101950.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i14.101950

Lipoma is a tumor of mature adipose tissue which may occur irrespective of the location with the presence of adipose tissue. Intraosseous lipomas are very rare benign lesions of bone, accounting for less than 0.1% of all bone neoplasms[1]. Bone lipoma can appear with mild and dull creeping pain, but can also be asymptomatic, making the diagnosis a challenge to orthopedic consultants. Therefore, most of the bone lipoma cases are easy to be misdiagnosed clinically and tend to be discovered incidentally during regular health examinations[2]. There have been very few previous studies related to osteolipoma, most of which are case reports. In this paper, the etiology, clinical features, imaging manifestations, differential diagnosis, and treatment of a case of distal tibial intraosseous lipoma were analyzed in combination with a review of relevant domestic and foreign literature, so as to improve clinician’s understanding of the disease.

A 21-year-old man presented to our outpatient service due to intermittent pain on his left leg for the past 4 years.

The patient was admitted to our hospital on February 26, 2018 on account of worsening of the recurrent pain on the left distal tibia 1 month before. In the past 4 years, the patient’s left lower limb often developed discontinuous dull pain with mild swelling, and the pain was aggravated after drastic exercises or standing for long time and relieved after rest. However, he had no history of trauma, fever, loss of weight, or decreased appetite.

The patient had no remarkable past medical history.

The patient had no remarkable personal and family history.

Upon physical examination, the patient was conscious and his breath was smooth breath. The vital signs were as follows: Respiratory rate, 16/minute; heart rate, 84/minute; temperature, 97.7 °F; and blood pressure, 122/70 mmHg. Systemic examination revealed physiological curvature of the spine, no tenderness or vertical percussion pain, free movement of four limbs, and normal muscle force and muscle strength. Neurological examination did not reveal any sign of meningeal irritation. There was local tenderness and swelling on the distal aspect of the left tibia, and the ankle range of motion was without any restrictions. The anterior medial tenderness of the distal left leg was positive, the mass was not palpable, the skin over the area did not show any abnormalities such as redness and swelling, ulceration, and the patient had no fever symptoms.

Hematological investigations showed alpha-fetoprotein 1.68 μg/L, carcinoembryonic antigen 3.13 μg/L, prostate-specific antigen 0.746 μg/L, interleukin-6 2.2 pg/mL, and procalcitonin 0.031 μg/mL, which did not yield any positive finding.

Radiographs revealed that bone density of the medial cortex of the left distal tibia was abnormal, showing an ellipsoidal increased density shadow, which was considered a fibrous bone lesion (Figure 1A). Computerized tomography (CT) revealed an irregular ground-glass opacity in the left distal tibia measuring about 24 mm × 8 mm in maximum diameter with slight thickening and sclerotic rim of the adjacent cortex. The lesion was regarded as either a benign fibrous histiocytoma or bone lipoma (Figure 1B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well-defined lesion of about 28 mm × 8 mm × 12 mm with a decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted image (T1WI) and low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted image (T2WI) in the medial subcortical bone of the left distal tibia. Moreover, there was uniform low-signal ring in the margins of the adjacent bone, suggesting it as a benign fibrous tumor, such as benign fibrous histiocytoma of bone or ossifying fibroma (Figure 1C).

The patient was diagnosed with intraosseous lipoma of the tibia.

Surgical curettage, bone graft, and internal fixation with steel plate under intraspinal anesthesia were performed on the patient.

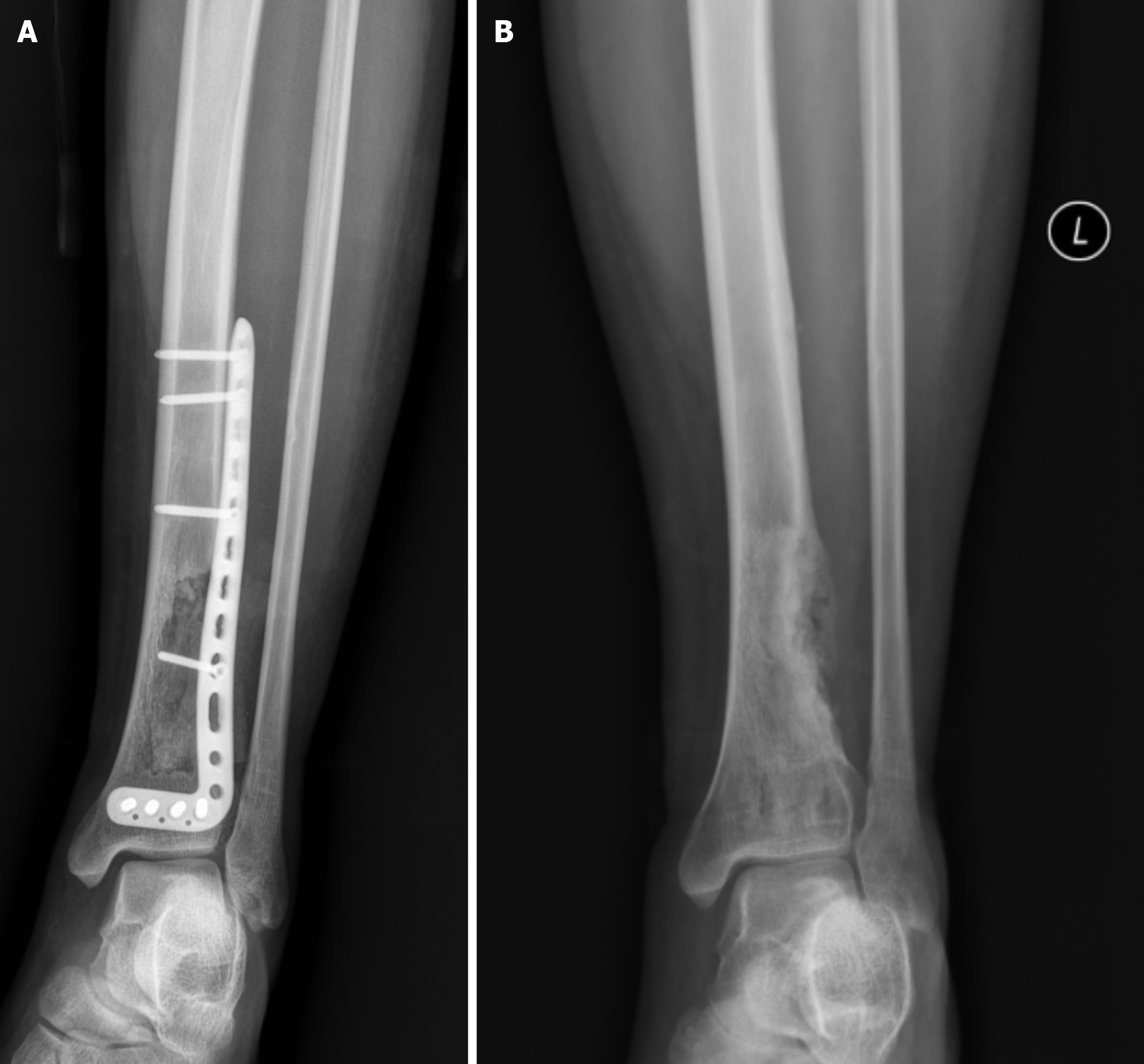

The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged from the hospital in good condition. At 1-month postoperative visit, radiographs taken revealed a considerable rectification of the local bone defect and uneven bone density in the left distal tibia. Moreover, the internal fixation position can also be clearly seen (Figure 2). At 30-month subsequent reexaminations, radiographs revealed that multiple bone grafting and bone fusion can be seen in the region of bone defect of the left distal tibia, without any evidence of local recurrence of the tumor (Figure 3). The patient was symptom-free and was able to resume normal daily activities without any restrictions.

We conducted a PubMed literature search using the keywords intraosseous and lipoma. Intraosseous lipoma accounts for no more than 0.1% of all bone tumors[3]. Bone lipoma is a benign tumor which normally originates from the medullary cavity, cortex, and bone surface. The vast majority of bone lipomas are derived from the medullary cavity and are extremely rare in the bone cortex[4]. Bone lipoma is very rare and the exact etiology is not yet clearly delineated. Some think that it is related to the genetic and congenital factors, primarily derived from bone marrow fat, while others consider that it is due to trauma, though fat degeneration, infective pathologies, and fat metaplasia were also documented in the past[5]. At present, most of the clinical experts assert that intraosseous lipoma is a primary tumor of marrow fat[4]. Bone lipoma most often involves the metaphysis of long tubular bones, especially the femur, tibia, fibula, and calcaneus[1], but it also sporadically occurs in other parts, such as the pelvis, vertebrae, sacrum, skull, mandible, maxilla, and rib[6]. Despite no sex predominance, the majority of patients with lipoma are middle-aged[7]; the patients ranged in age from 10 years old to 80 years old, and most of them are diagnosed at about 40 years old[8]. Bone lipoma can be asymptomatic and can also appear with chronic dull pain and swelling after strenuous daily activities, with rarely accompanying pathological fractures[2]. Intraosseous lipoma has no characteristic imaging manifestations, so it is often easy to be misdiagnosed or missed in clinics, and there is a risk of pathological fracture. In addition, although intraosseous lipoma is a rare benign tumor, malignancy has been reported, so it needs to be evaluated properly[5]. Milgram published the first report of the association between bone lipomas and malignant transformation, and described that involuted bone lipomas contain the same cellular constituents as bone infarcts (intramedullary osteonecrosis), for that reason it should not be a surprise that an intraosseous lipoma might undergo malignant transformation, variously described as malignant fibrous histiocytoma, fibrosarcoma, or liposarcoma[7]. Xue et al[9] conducted a retrospective analysis of 19 patients with osteolipoma, with the age distribution ranging from 24 years old to 76 years old, among which the majority were from 40 years old to 50 years old. There were seven cases of calcaneus, five cases of femur, two cases each of humerus and radius, and one case each of tibia, fibula, and metatarsal osteolipoma. Fifteen patients had clinical symptoms (pain and swelling), three had no symptoms in physical examination, and the other one had bone cyst curettage.

The main X-ray manifestations of intraosseous lipoma are osteolytic destruction, round or oval low-density shadow, clear boundary of transparent area, hardening boundary around the lesion, residual bone trabeculae, and rarely cortical expansion, without any periosteal reaction or “cartilage cap” sign[9]. The X-ray signs are not specific, based on which it is difficult to distinguish intraosseous lipoma from other diseases, so CT and MRI are often recommended to distinguish them. CT showed transparent lesions with the same local density as normal fat, with clear boundaries, bone trabecular absorption, but less involvement of bone cortex and no signs of periosteal reaction[2]. The reactive hyperplasia of bone around the focus formed an irregular bony septum, in which nodular calcification could be seen (which may be related to calcinosis after adipose tissue necrosis)[10]. The CT value of intraosseous lipoma is the same as that of subcutaneous fat, mostly between approximately -100 Hu and 50 Hu (the CT value of our patient is -71 Hu), and the CT value can help to preliminarily diagnose whether it is a fatty lesion. MRI has unique advantages in the qualitative diagnosis of intraosseous lipoma. Intraosseous lipoma shows high signal intensity both on T1WI and T2WI, and the signal intensity of intraosseous lipoma decreases significantly in the fat suppression sequence, which is the same as that of subcutaneous fat[11]. MRI examination also showed that the necrosis and cystic degeneration in the tumor showed high signal intensity in the T2WI sequence, while the calcification in the focus showed low signal intensity in the T2WI sequence, and the enhancement sequence was not enhanced[2]. In the past, pathological diagnosis was considered as the gold standard for the diagnosis of bone lipoma. At present, according to the international norms, it is believed that calcaneal lipoma can be diagnosed by imaging in general, but may not be necessary to pass pathological diagnosis[10].

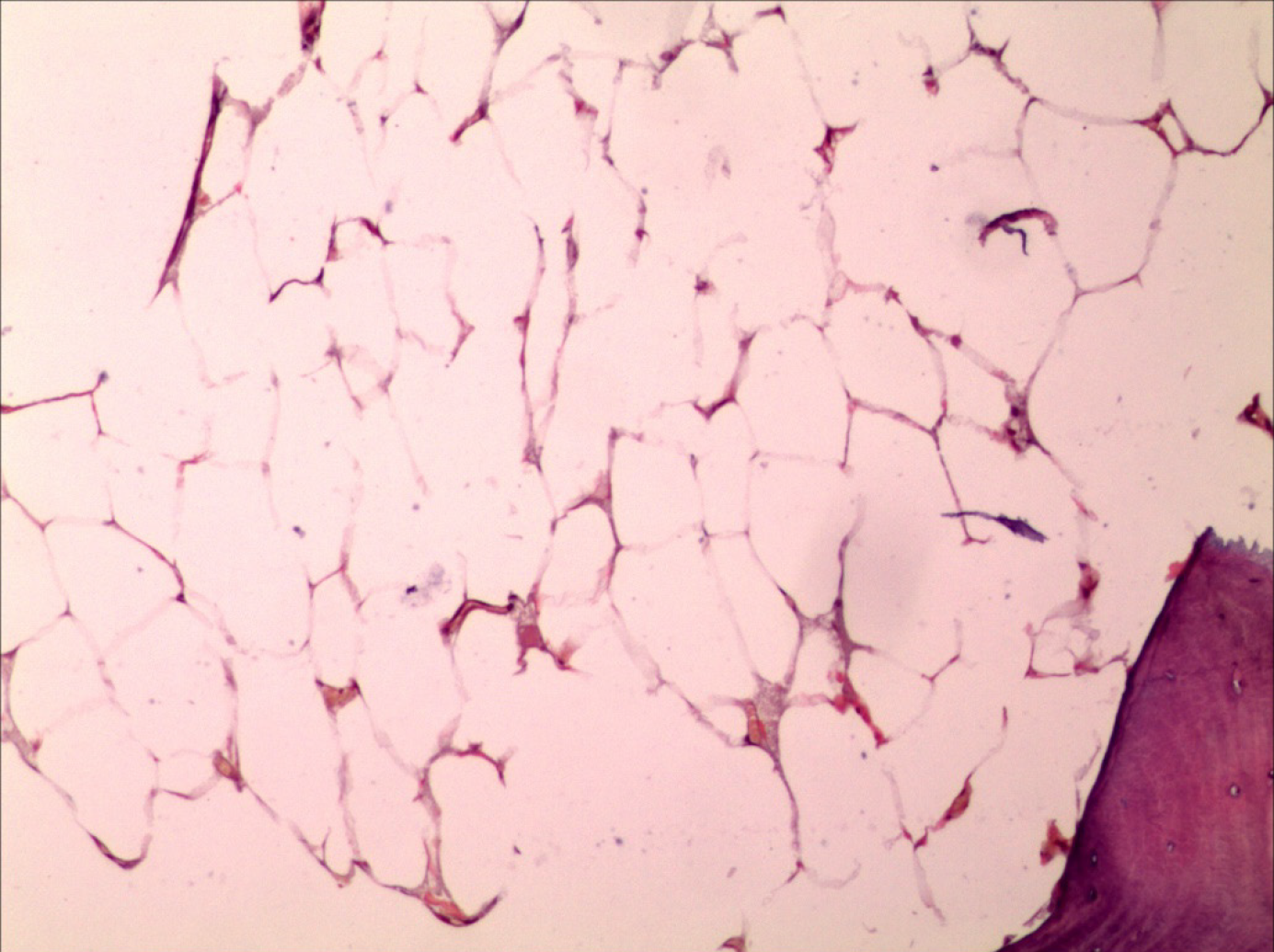

The defining histopathologic features of intraosseous lipoma are the early resorption of trabecular bone and the presence of fat. Milgram introduced the staging system for intraosseous lipoma, which is based on the ratio of viable to necrotic fat cells within the lesion. Intraosseous lipoma can be divided into three stages[12]: (1) Stage I is the destruction of bone tissue, replaced by viable adipocytes, and the focus is transparent; (2) Stage II is characterized by punctate calcification due to partial fat necrosis and calcification, surrounded by vital fat cells with sclerotic edges; and (3) In stage III, adipocyte necrosis, calcification with cystic degeneration, surrounded by ossification, and an opaque area with increased density are seen on radiology. The progression of Milgram’s three stages is produced by the increase in intralesional pressure as a result of cell proliferation. Milgram has reported four cases of malignant transformation of intraosseous lipoma, of which three occurred in stage III. In case of malignant transformation of intraosseous lipoma, clinicians should be alert to the rapid bone destruction, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and liposarcoma[7].

The histologic or imaging manifestations of intraosseous lipoma are often similar to those of many diseases, such as chondroblastoma, bone cyst, Brodie’s abscess, osteofibrous dysplasia, giant cell tumor, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma[2,13-15]. Thus, in the face of an indeterminate diagnostic situation in a case, we should fully consider the probability of all these relevant diseases rather than taking into account only bone lipoma. Histological examination can distinguish between bone lipoma and osteofibrous dysplasia, because the latter is a fibro-osseous spindle cell lesion devoid of fat[16]. Bone fibrodysplasia is a preference for the intracortical lesion of the tibia in children, and therefore it should be considered more for osteofibrous dysplasia than for intracortical lipoma toward intracortical lesion of the tibia[16]. Biopsy usually testifies trait of inflammation and osteonecrosis of Brodie’s abscess[14]. In addition, chondroblastoma, osteoblastoma, and osteoid osteoma are readily differentiated from intraosseous lipoma through their micro-morphology or imaging findings[16]. Giant cell tumors most often involves the metaphysis of long tubular bones and are characterized by soap-like structures. Moreover, giant cell tumors and bone cysts show long T1WI and T2WI signals on MRI[17].

So far, there are two views on the treatment of bone fat lipoma: Conservative treatment and surgical treatment. Some scholars believe that for asymptomatic or mild symptoms of intraosseous lipoma that has not affected the daily life of patients, it is recommended to take conservative treatment and proceed with observation and a regular follow-up every 6 months[1]. Because intraosseous lipoma is a benign tumor, malignant transformation is rare. In patients with no signs of an impending pathologic fracture or suspicion of malignancy, clinical and radiological follow-up is sufficient. Another group of scholars believe that intraosseous lipoma will have complications such as pathological fracture, infection, and malignant tendency, and they advocate active surgical treatment[1]. Focus curettage + autologous/allogeneic bone transplantation + internal fixation is the main choice of operation. The indications of surgical treatment include: (1) Long-term pain in the lesion site, which affects the quality of life; (2) Pathological fracture; and (3) Tumor grows too fast and tends to become malignant[11]. Bone lipoma has a good prognosis and rarely recurs after surgical resection[8]. This patient had intermittent pain in the left lower limb for more than 4 years and worsened for 2 weeks. He was admitted to hospital for resection of the lesion of the distal left tibia, right iliac bone grafting, and internal plate fixation. The internal fixation plate was removed 1 year later, and now more than 2 years after operation, there was no obvious pain and discomfort in the left lower limb, and the activity was not limited. Reexamination showed that there was no tumor recurrence.

In conclusion, the case of intraosseous lipoma reported in this paper had no obvious clinical symptoms and no characteristic X-ray imaging features, so imaging examination could only hint the diagnosis of intraosseous lipoma but could not discriminate other disasters. A combination of CT, MRI, and biopsy should be utilized to make the final diagnosis. In contrast, many clinicians from different countries even assert that the diagnosis can only be relied on simple CT and MRI without any biopsy[10]. On occasions, bone lipoma that is asymptomatic can be treated via conservative management approach. For patients with surgical indications, however, surgical curettage of tumor and bone grafting or cementation is most often deemed to be a conventional treatment modality in many cases. The purpose of this paper is to increase the awareness among orthopedic surgeons of the existence of this disease, by means of conducting a retrospective study with the lipoma in the left distal tibia of a young man from wide prospects of clinical manifestations, radiologic imaging, pathological features, and postoperative effect.

| 1. | Frangež I, Nizič-Kos T, Cimerman M. Threatening Fracture of Intraosseous Lipoma Treated by Internal Fixation (Case Report and Review of the Literature). J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2019;109:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Belzarena AC, Paladino LP, Henderson-Jackson E, Joyce DM. Intraosseous lipoma of the clavicle with extraosseous extension. Radiol Case Rep. 2020;15:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Salgado M, Córdova C, Avilés C, Fernández F. A Case Report of Curettage and Kryptonite(®) use in Proximal Femur Intraosseous Lipoma. J Orthop Case Rep. 2016;6:98-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Basheer S, Abraham J, Shameena P, Balan A. Intraosseous lipoma of mandible presenting as a swelling. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2013;17:126-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sharma PK, Kundu ZS, Tiwari V, Digge VK, Sharma J. Intraosseous Lipoma of the Calcaneum. Cureus. 2021;13:e16929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Waśkowska J, Wójcik S, Koszowski R, Drozdzowska B. Intraosseous Lipoma of the Mandibula: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Open Med (Wars). 2017;12:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipomas. A clinicopathologic study of 66 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;277-302. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Kang HS, Kim T, Oh S, Park S, Chung SH. Intraosseous Lipoma: 18 Years of Experience at a Single Institution. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018;10:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Xue W, Wang ZP, Guan XL, Liu L, Qian YW. [Intraosseous lipoma: retrospective analysis of 19 patients]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2017;30:279-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pappas AJ, Haffner KE, Mendicino SS. An intraosseous lipoma of the calcaneus: a case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;53:638-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Castañeda Martinez AI, Pala E, Cappellesso R, Trovarelli G, Ruggieri P. Intraosseous lipoma of the patella: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Biomed. 2021;92:e2021084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Milgram JW. Intraosseous lipomas: radiologic and pathologic manifestations. Radiology. 1988;167:155-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Palczewski P, Swiątkowski J, Gołębiowski M, Błasińska-Przerwa K. Intraosseous lipomas: A report of six cases and a review of literature. Pol J Radiol. 2011;76:52-59. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Strobel K, Hany TF, Exner GU. PET/CT of a brodie abscess. Clin Nucl Med. 2006;31:210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | de Moraes FB, Paranahyba RM, do Amaral RA, Bonfim VM, Jordão ND, Souza RD. Intraosseous lipoma of the iliac: case report. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51:113-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zuloaga CB, Araya Salas C, Rebolledo Urbina J, Muñoz Roldan A. Intraosseous lipoma: a case report. Revista Odonto Ciência. 2018;33:117-120. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Han XK, Yang WG, Ma ZL, Fang W, He XF. [A case report of intraosteo-lipoma of talus]. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2013;26:270-271. [PubMed] |