Published online Apr 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i11.101668

Revised: November 19, 2024

Accepted: December 5, 2024

Published online: April 16, 2025

Processing time: 94 Days and 16.3 Hours

Hepatic hemangiomas can be challenging to diagnose, particularly when they present with atypical features that mimic other conditions, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). This case highlights the diagnostic difficulties encoun

A 44-year-old woman presented with intermittent abdominal distension and heartburn for three months. Her medical history included iron deficiency anemia, menorrhagia, and previous cholecystectomy. One week prior to admission, an endoscopy suggested a bulging gastric fundus, which was likely a GIST, along with chronic nonatrophic gastritis and bile reflux. CT and EUS revealed nodules in the gastric fundus, which were initially considered benign tumors with a differential diagnosis of stromal tumor or leiomyoma. During surgery, unexpected lesions were found in the liver pressing against the gastric fundus, leading to laparoscopic liver resection. Postoperative pathology confirmed the diagnosis of hepatic cavernous hemangiomas. The patient recovered well and was discharged five days later, with normal follow-up results at three months.

This case underscores the challenges in the preoperative diagnosis of GISTs, particularly the limitations of the use of CT and EUS for the evaluation of sube

Core Tip: Hepatic hemangiomas can be challenging to diagnose, especially when they mimic other conditions like gastrointestinal stromal tumors. This case highlights the limitations of imaging techniques such as computerized tomography and endoscopic ultrasound in diagnosing subepithelial lesions. While computerized tomography is effective for visualizing abdominal tumors, it struggles to detect smaller lesions and assess the gastrointestinal wall layers. Endoscopic ultrasound is helpful for evaluating smaller nodules, but its diagnostic accuracy is limited. This case emphasizes the importance of considering hepatic lesions when gastrointestinal symptoms are present, particularly when imaging findings are in

- Citation: Wang JZ, Chen H. Hepatic hemangiomas mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(11): 101668

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i11/101668.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i11.101668

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare tumors that can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, with the most common site being the stomach. Approximately 15%-30% of patients with GISTs are asymptomatic, with the most common symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, and bleeding[1]. GISTs should be diagnosed through immunohistochemical analysis, including the assessment of KIT and CD34 and/or discovered on GIST 1[2]. However, since GISTs are subepithelial lesions (SELs), obtaining a conclusive histologic diagnosis through standard endoscopic forceps biopsy is relatively challenging. The preoperative diagnosis of GISTs relies on imaging examinations such as computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography, and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)[3]. We present a case of hepatic hemangioma that was initially misdiagnosed as a GIST and discuss our findings in relation to the diagnosis of GISTs and hepatic hemangiomas on the basis of a review of the literature.

A 44-year-old female patient was admitted to the oncological surgery department with complaints of intermittent abdominal distension and heartburn for 3 months.

An endoscopic examination one week prior to admission revealed a bulging gastric fundus. A GIST was considered the likely diagnosis, as well as chronic nonatrophic gastritis with bile reflux.

The patient’s relevant past medical history included iron deficiency anemia, menoxenia, and cholecystectomy for gallbladder stones.

The patient had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption. There was no relevant family medical history.

The physical examination did not reveal any abnormalities.

The clinical examination was unremarkable.

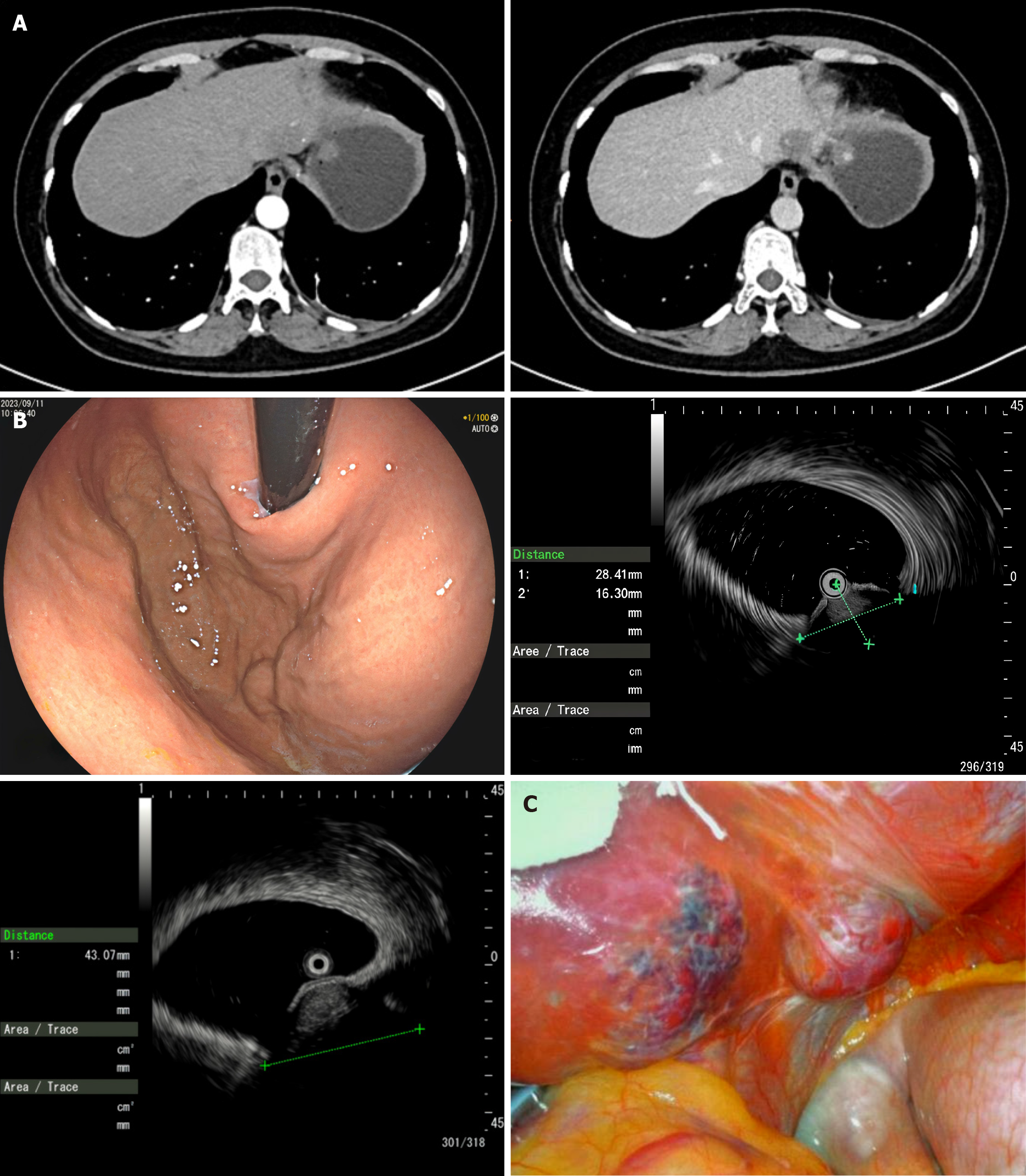

An enhanced CT scan revealed two circular nodules in the fundus of the stomach measuring approximately 1.8 cm × 1.3 cm and 2.3 cm × 1.6 cm (Figure 1A), leading to the consideration of a benign gastric tumor, with the differential diagnosis including a stromal tumor and a leiomyoma. EUS revealed two connected spherical bulges in the anterior wall of the fundus of the stomach, with diameters of 28 mm and 43 mm (Figure 1B), both with normal mucosa. The lesions appeared hypoechoic from the muscularis propria and appeared to be growing toward the outer cavity, with uniform internal echo and attenuated rear echo. Combining the findings from CT and EUS, the diagnosis was thought to be GISTs.

Patient diagnosed with hepatic hemangioma.

Preoperatively, an endoscopic injection of indocyanine green was administered to mark the incisal margin during fluorescence laparoscopy. During laparoscopy under general anesthesia, two unexpected lesions were found in the left lobe of the liver, while the gastric surface appeared normal (Figure 1C). These hepatic lesions were pressing on the fundus of the stomach. Intraoperative gastroscopy confirmed that the lesions originated from extragastric compression. Subsequently, laparoscopic liver partial resection was performed.

Postoperative pathological examination confirmed that the hepatic lesions were hepatic cavernous hemangiomas. The patient recovered well after surgery and was discharged 5 days later. Follow-up was normal at 3 months.

This report describes a case of misdiagnosis as GISTs despite detailed preoperative examinations involving CT, endoscopy, and EUS. CT is the primary method used to visualize tumors in the abdominal cavity; however, the limitation of CT for the evaluation of SELs is that it cannot easily be used to analyze smaller lesions and does not allow the accurate evaluation of the gastrointestinal wall layers[4]. GISTs larger than 5 cm in diameter typically appear exophytic and hypervascular on CT[2]. In contrast, CT can readily be used to identify hepatic cavernous hemangiomas. These lesions present with early peripheral nodular enhancement in the arterial phase and progress slowly, with centripetal filling in the portal venous phase[5]. Although these imaging features may not be detected when the lesions are smaller than 5 mm in diameter[6], this typical enhancement pattern makes them easy to distinguish from GISTs. The ESMO guidelines recommend EUS assessment as the standard approach for patients with esophagogastric or duodenal nodules measuring < 2 cm in diameter[7]. EUS can be used to accurately discriminate an SEL suspected of being a GIST (hypoechoic solid mass) from other SELs, including lipomas, cysts, varices, and extragastrointestinal compression[8]. The finding of a hypoechoic solid mass on EUS can also be seen with malignant tumors, such as malignant lymphoma, metastatic cancers, neuroendocrine tumors, and SEL-like cancers, as well as in benign conditions such as leiomyoma, neurinoma, and an aberrant pancreas. It is difficult to distinguish among these lesions on the basis of EUS findings alone. The accuracy of the differential diagnosis of SELs on the basis of EUS is extremely poor and ranges from 45.5%-48.0%[4]. The problem lies in the location of the lesion; the left outer lobe of the liver is closer to the anterior wall of the fundus stomach. In this case, both CT and EUS required distention of the stomach, which further pressed the liver tumor against the stomach wall, making it appear as if it were stomach wall lesion. We have outlined the key imaging characteristics used in the differential diagnosis of hepatic hemangiomas and GISTs (Table 1).

| CT | MRI | PET/CT | US | EUs | |

| GIST | Initial diagnostic modality, size ≤ 2 cm, low detection; size > 2 cm, peripheral enhancement pattern, exophytic and hypervascular[4] | Similar to CT imaging, low signal intensity on T1WI, high signal intensity on T2WI, and enhanced signal intensity on post gadolinium image[13] | Shows a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 97%[14] | Use for the diagnosis of hepatic metastases | size < 2 cm, hypoechoic solid mass accurately identifying a SEL[7] |

| Hepatic hemangioma | High detection, early peripheral nodular enhancement in the arterial phase and slow, progressive centripetal filling in the portal venous phase[9] | Differential diagnosis with other liver tumors, low signal intensity on T1WIs and appear hyperintense on diffusion-weighted imaging[15] | - | Initial diagnostic modality, presents as hyperechoic, or as hypoechoic masses with a hyperechoic rim[15] | - |

However, it is quite rare for a hepatic hemangioma located in the left lobe of the liver to present as a GIST. Some researchers have identified pedunculated hepatocellular carcinoma (P-HCC) as a condition that can mimic GISTs[9,10]. The diagnosis of P-HCC, particularly type II P-HCC, presents significant challenges. P-HCCs located in the left lobe of the liver are more prone to misdiagnosis as GISTs than are hepatic hemangiomas found in the same anatomical region. Some researchers believe that, with the careful analysis of imaging features, MRI can lead to more reliable diagnoses[10-12].

This case report highlights the diagnostic challenges faced when distinguishing hepatic hemangiomas from GISTs, particularly when the lesion is located in the left lobe of the liver and exerts pressure on the stomach wall. Despite detailed preoperative evaluations involving CT, endoscopy, and EUS, a hepatic hemangioma can be mistakenly diagnosed as a GIST due to overlapping imaging characteristics. Importantly, while CT and EUS are invaluable tools for assessing gastrointestinal tumors, their limitations with regard to the evaluation of SELs and differentiation among extragastric lesions, such as hepatic hemangiomas, underscore the importance of considering a broad differential diagnosis. The importance of careful imaging analysis and, when necessary, intraoperative exploration to ensure an accurate diagnosis and avoid mismanagement is emphasized. This case also underscores the need for a multimodal approach, incorporating MRI and other advanced techniques, to refine the preoperative diagnosis and guide the selection of appropriate treatments.

| 1. | Chi P, Chen Y, Zhang L, Guo X, Wongvipat J, Shamu T, Fletcher JA, Dewell S, Maki RG, Zheng D, Antonescu CR, Allis CD, Sawyers CL. ETV1 is a lineage survival factor that cooperates with KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Nature. 2010;467:849-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Mantese G. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2019;35:555-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Wu CE, Tzen CY, Wang SY, Yeh CN. Clinical Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST): From the Molecular Genetic Point of View. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Sepe PS, Brugge WR. A guide for the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:363-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Roebuck D, Sebire N, Lehmann E, Barnacle A. Rapidly involuting congenital haemangioma (RICH) of the liver. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Aziz H, Brown ZJ, Eskander MF, Aquina CT, Baghdadi A, Kamel IR, Pawlik TM. A Scoping Review of the Classification, Diagnosis, and Management of Hepatic Adenomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;26:965-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Casali PG, Blay JY, Abecassis N, Bajpai J, Bauer S, Biagini R, Bielack S, Bonvalot S, Boukovinas I, Bovee JVMG, Boye K, Brodowicz T, Buonadonna A, De Álava E, Dei Tos AP, Del Muro XG, Dufresne A, Eriksson M, Fedenko A, Ferraresi V, Ferrari A, Frezza AM, Gasperoni S, Gelderblom H, Gouin F, Grignani G, Haas R, Hassan AB, Hindi N, Hohenberger P, Joensuu H, Jones RL, Jungels C, Jutte P, Kasper B, Kawai A, Kopeckova K, Krákorová DA, Le Cesne A, Le Grange F, Legius E, Leithner A, Lopez-Pousa A, Martin-Broto J, Merimsky O, Messiou C, Miah AB, Mir O, Montemurro M, Morosi C, Palmerini E, Pantaleo MA, Piana R, Piperno-Neumann S, Reichardt P, Rutkowski P, Safwat AA, Sangalli C, Sbaraglia M, Scheipl S, Schöffski P, Sleijfer S, Strauss D, Strauss SJ, Hall KS, Trama A, Unk M, van de Sande MAJ, van der Graaf WTA, van Houdt WJ, Frebourg T, Gronchi A, Stacchiotti S; ESMO Guidelines Committee, EURACAN and GENTURIS. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: ESMO-EURACAN-GENTURIS Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:20-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 106.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga T, Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2806-2817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 9. | Kawabe N, Higashiguchi T, Yasuoka H, Kawai T, Kamio K, Ochi T, Hayashi C, Shimura M, Furuta S, Arakawa S, Kondo Y, Asano Y, Nagata H, Ito M, Horiguchi A, Morise Z. A case of hepatocellular adenoma with pedunculated development and difficulty in diagnosis. Fujita Med J. 2020;6:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Shafaee Z, Liu S, Isabel Fiel M, Blue R. Erratum to "Giant pedunculated hepatocellular adenoma masquerading as a subdiaphragmatic mass: Diagnostic challenges of a rare tumor" [Radiology Case Reports 16 (2021) 84-89]. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:3452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | de Araújo EM, Torres US, Pria HD, Torres LR, Pedroso MHNI, Racy DJ, D'Ippolito G. Anatomy and Imaging of Accessory Liver Lobes: What Radiologists Should Know. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2022;43:476-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Horie Y, Kitano M, Koda M, Katoh S, Sutou Y, Ohta Y, Kawasaki H. Diagnostic usefulness of MR imaging for pedunculated hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Imaging. 1994;18:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Caramella T, Schmidt S, Chevallier P, Saint Paul M, Bernard JL, Bidoli R, Bruneton JN. MR features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Imaging. 2005;29:251-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Inoue A, Ota S, Yamasaki M, Batsaikhan B, Furukawa A, Watanabe Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive radiological review. Jpn J Radiol. 2022;40:1105-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Kacała A, Dorochowicz M, Matus I, Puła M, Korbecki A, Sobański M, Jacków-Nowicka J, Patrzałek D, Janczak D, Guziński M. Hepatic Hemangioma: Review of Imaging and Therapeutic Strategies. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |