Published online Mar 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1660

Peer-review started: October 30, 2023

First decision: December 29, 2023

Revised: January 10, 2024

Accepted: March 5, 2024

Article in press: March 5, 2024

Published online: March 26, 2024

Processing time: 146 Days and 16 Hours

Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH) triggered by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is rare in pediatric patients. There is no consensus on how to treat S. typhimurium-triggered sHLH.

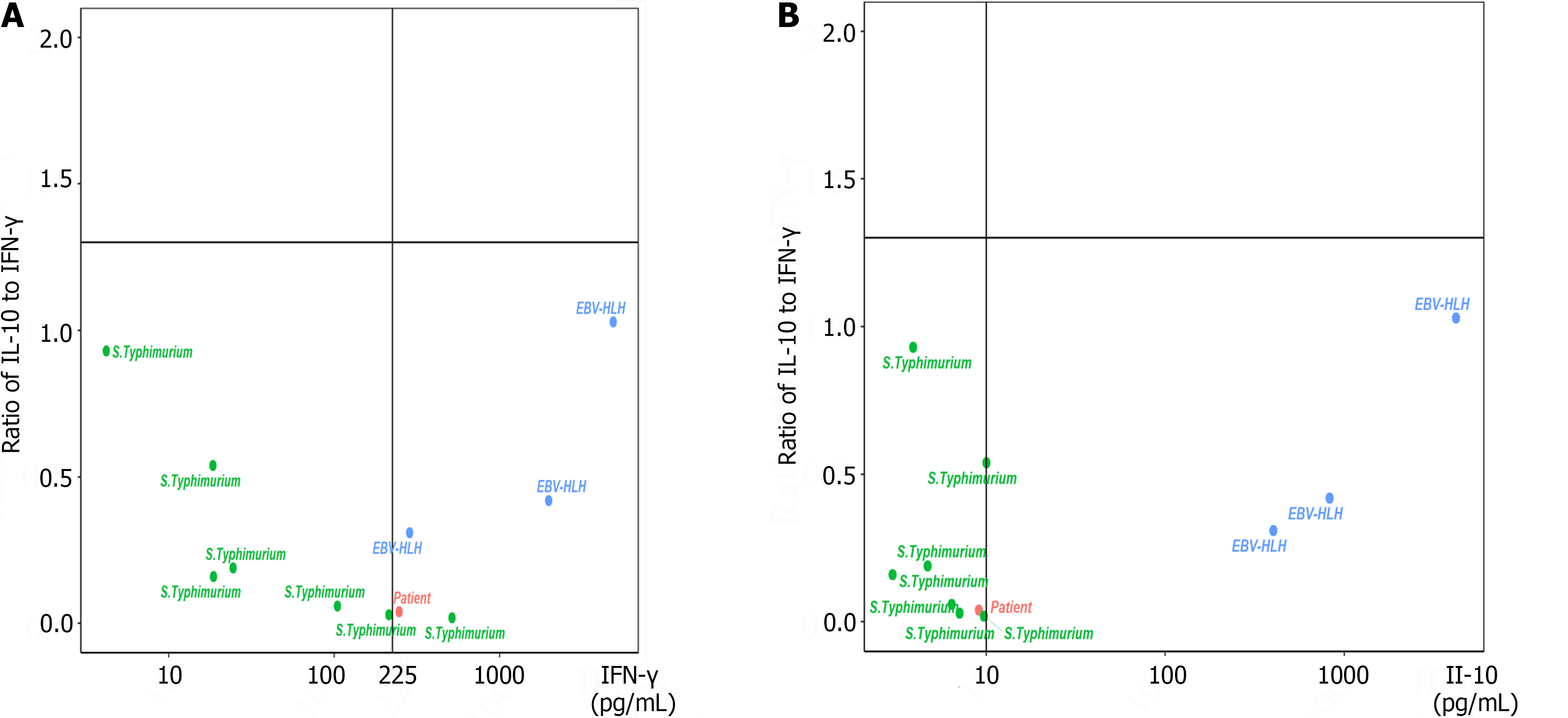

A 9-year-old boy with intermittent fever for 3 d presented to our hospital with positive results for S. typhimurium, human rhinovirus, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. At the time of admission to our institution, the patient’s T helper 1/T helper 2 cytokine levels were 326 pg/mL for interleukin 6 (IL-6), 9.1 pg/mL for IL-10, and 246.7 pg/mL for interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), for which the ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ was 0.04. In this study, the patient received meropenem, linezolid, and cefoperazone/sulbactam in combination with high-dose methylprednisolone therapy (10 mg/kg/d for 3 d) and antishock supportive treatment twice. After careful evaluation, this patient did not receive HLH chemotherapy and recovered well.

S. Typhimurium infection-triggered sHLH patient had a ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ ≤ 1.33, an IL-10 concentration ≤ 10.0 pg/mL, and/or an IFN-γ concentration ≤ 225 pg/mL at admission. Early antimicrobial and supportive treatment was sufficient, and the HLH-94/2004 protocol was not necessary under these conditions.

Core Tip:Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is one kind of pathogen that can trigger secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (sHLH). There is no consensus on how to treat S. Typhimurium-triggered sHLH. Compared to controls, an S. Typhimurium-triggered sHLH patient showed a ratio of interleukin-10 (IL-10) to interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) ≤ 1.33, an IL-10 concentration ≤ 10.0 pg/mL, and/or IFN-γ concentration ≤ 225 pg/mL on admission. The HLH-94/2004 protocol was not necessary, and early antimicrobial and supportive treatment was sufficient.

- Citation: Chen YY, Xu XZ, Xu XJ. Low interleukin-10 level indicates a good prognosis in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium-induced pediatric hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(9): 1660-1668

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i9/1660.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1660

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome composed of clinical findings such as fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, hypertriglyceridemia, hypofibrinogenemia, hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow or spleen or lymph nodes, low or absent natural killer cell activity, and elevated levels of serum ferritin (SF) and soluble cluster of differentiation 25 (CD25)[1]. HLH comprises two conditions: primary HLH (pHLH) and secondary HLH (sHLH). pHLH occurs in the presence of an underlying predisposing genetic defect in the cytolytic pathway, whereas sHLH is acquired in the setting of an infectious, malignant, or autoimmune cause without genetic defects[2].

sHLH can be triggered by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)[3], cytomegalovirus[4], and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium[5,6], etc. S. typhimurium is a Gram-negative bacterium that depends on an essential inflammatory response to colonize the intestinal tract, causing self-limiting gastroenteritis in humans[7,8]. S. typhimurium alone, in some animal models, could be an independent trigger of sHLH[9]. Some pediatric patients infected with S. typhimurium progress to sHLH[10]. Cytokine storm syndrome is a life-threatening systemic inflammatory state characterized by elevated levels of circulating cytokines and immune cell hyperactivation[11]. In our previous study, we reported a specific cytokine pattern for HLH: interleukin 10 (IL-10) > 60 pg/mL, interferon gamma (IFN-γ) > 75 pg/mL, and IL-6 > 51.1 pg/mL[12]. Patients with a ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ > 1.33 combined with IFN-γ ≤ 225 pg/mL were considered to have pHLH, whereas sHLH patients usually had a ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ ≤ 1.33[13]. Moreover, an IL-10 concentration ≥ 456 pg/mL was an independent prognostic factor for early death[14].

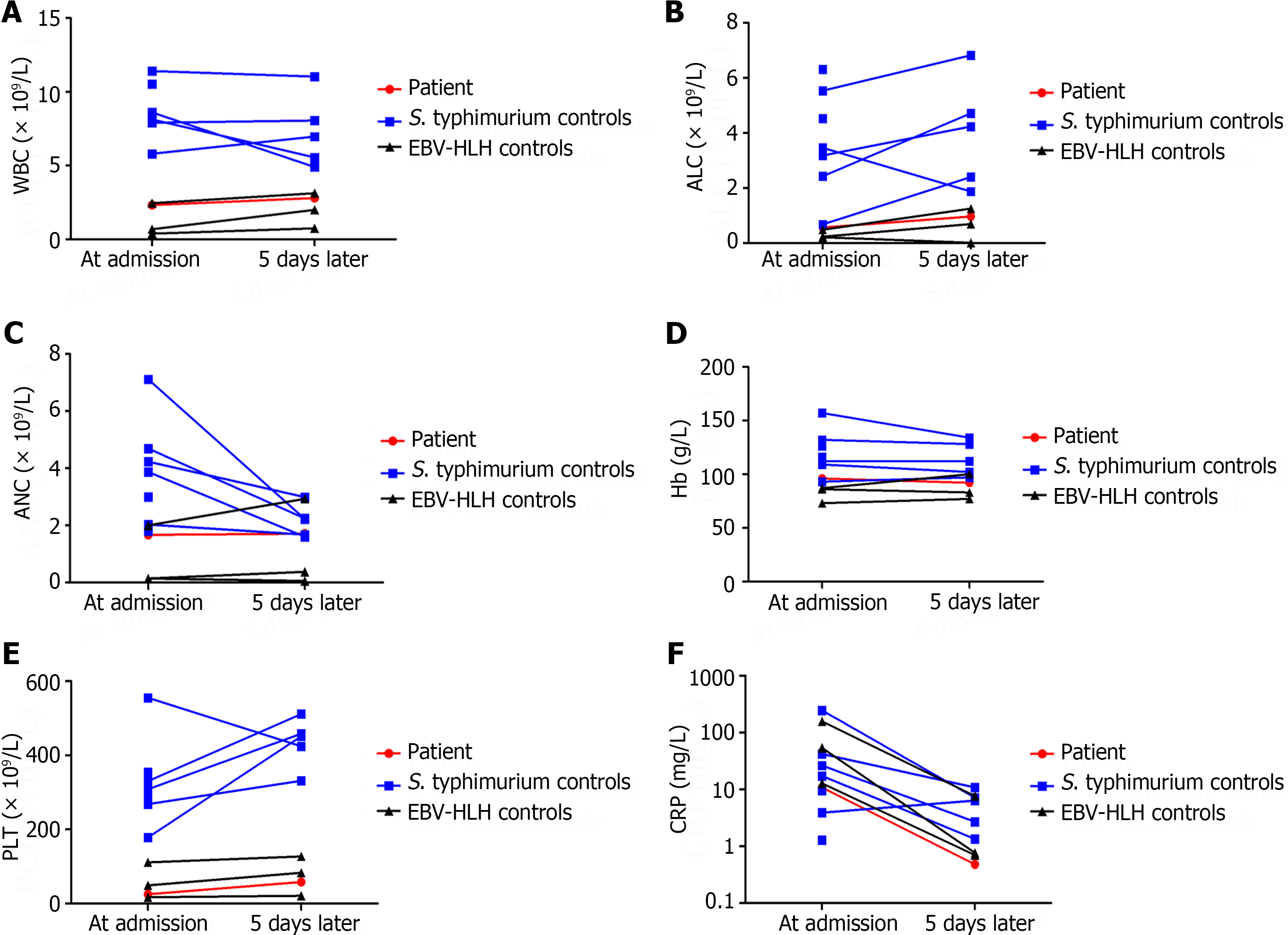

In this study, a patient who developed HLH due to S. typhimurium infection is described. His IL-10 concentration was 9.1 pg/mL, and the ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ was 0.04 at admission. Seven patients infected with S. typhimurium and three EBV-HLH patients were included as controls. The HLH patient did not receive chemotherapy, and after anti-infection therapy and supportive treatments, he recovered very well.

A 9-year-old Chinese boy was admitted to the hospital due to an intermittent fever for 3 d.

Approximately 3 d before admission, the patient presented with a fever of 39.3 °C without any inductive or provocative factors, and his complete blood count (CBC) showed pancytopenia. His white blood cell count was 2.33 × 109/L, his hemoglobin level was 96 g/L, and his platelet was 25 × 109/L. He did not have any symptoms of cough, vomiting, or diarrhea.

The patient had no relevant medical history.

There were no special features in the patient's background or family history, and there was no consanguinity.

At the time of admission, the patient had an intermittent fever for 3 d. His abdomen was distended, and there was no enlargement of the spleen or liver below his costal margins. No palpable lymphadenopathy was observed. Physiological reflexes were normal. The Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination scar was normal, and no rashes were observed on his skin. The vital signs of the patient during hospitalization are shown in Table 1.

| Testing date | WBC as × 109/L | ALC as × 109/L | ANC as × 109/L | Hb in g/L | PLT as × 109/L | CRP in mg/L | PCT in ng/mL | Fib in g/L | TG in mmol/L | SF in mg/L | T in C | HR, times/min | RR, times/min | BP in mmHg | SpO2, % |

| September 25, 2022 | 2.33 | 0.57 | 1.63 | 96 | 25 | 10.88 | 2.32 | 2.23 | 1.03 | > 1500 | 39.4 | 128 | 20 | 78/40 | > 95% |

| September 26, 2022 | 2.74 | 0.83 | 1.8 | 109 | 36 | 11.52 | 2.8 | 1.93 | 1.39 | > 1500 | 35.6 | 16 | 30 | 91/70 | > 95% |

| September 27, 2022 | 2.75 | 0.76 | 1.91 | 98 | 26 | 6.2 | 2.6 | NT | NT | NT | 35.5 | 78 | 20 | 103/67 | > 95% |

| September 28, 2022 | 2.14 | 0.82 | 1.2 | 87 | 76 | 2.69 | NT | NT | NT | 1835.0 | 35.8 | 74 | 18 | 105/73 | > 95% |

| September 29, 2022 | 2.51 | 1.08 | 1.23 | 89 | 70 | 1.01 | NT | 1.26 | NT | NT | 36.0 | 77 | 19 | 100/75 | > 95% |

| September 30, 2022 | 2.81 | 0.97 | 1.71 | 92 | 58 | 0.48 | NT | 1.12 | 1.7 | NT | 36.0 | 102 | 18 | 83/54 | > 95% |

| October 2, 2022 | 4.82 | 3.03 | 1.58 | 87 | 37 | 0.64 | NT | 1.59 | NT | 725.2 | 37.3 | 86 | 20 | 86/60 | > 95% |

| October 3, 2022 | 3.93 | 2.23 | 1.63 | 81 | 38 | 0.38 | 0.291 | NT | NT | NT | 37.1 | 72 | 22 | 72/44 | > 95% |

| October 4, 2022 | 6.31 | 4.73 | 1.35 | 84 | 29 | 0.5 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 38.4 | 123 | 23 | 90/58 | > 95% |

| October 5, 2022 | 4.11 | 2.72 | 1.19 | 77 | 31 | 0.87 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 37.9 | 112 | 22 | 82/57 | > 95% |

| October 6, 2022 | 4.04 | 2.94 | 0.94 | 74 | 50 | 1.1 | 0.118 | NT | NT | NT | 38.6 | 154 | 28 | 87/56 | > 95% |

| October 7, 2022 | 3.67 | 2.78 | 0.68 | 77 | 50 | 1.79 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 37.8 | 120 | 16 | 97/69 | > 95% |

| October 8, 2022 | 3.73 | 2.99 | 0.55 | 75 | 50 | 1.37 | NT | 3.44 | NT | 384.5 | 37.6 | 136 | 22 | 75/51 | > 95% |

| October 9, 2022 | 3.53 | 2.36 | 0.92 | 105 | 50 | 0.92 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 37.6 | 105 | 23 | 108/76 | > 95% |

| October 10, 2022 | 3.98 | 3.05 | 0.69 | 93 | 48 | 0.9 | NT | NT | NT | 332.5 | 37.6 | 95 | 24 | 111/77 | > 95% |

| October 11, 2022 | 4.78 | 3.64 | 0.88 | 99 | 56 | 1.3 | 0.096 | NT | NT | NT | 37.3 | 131 | 20 | 128/84 | > 95% |

| October 12, 2022 | 5.89 | 4.78 | 0.73 | 98 | 54 | 1.08 | NT | NT | 1.11 | NT | 37.2 | 104 | 26 | 84/59 | > 95% |

| October 14, 2022 | 5.1 | 4.05 | 0.66 | 97 | 56 | 1.14 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 37.2 | 117 | 22 | 97/60 | > 95% |

| October 15, 2022 | 6.06 | 4.82 | 0.77 | 99 | 63 | 0.41 | NT | NT | NT | NT | 36.3 | 105 | 20 | 90/62 | > 95% |

| October 16, 2022 | 7.05 | 5.69 | 0.88 | 101 | 74 | 0.41 | NT | NT | NT | 346 | 36.5 | 120 | 23 | 97/67 | > 95% |

His soluble CD25 concentration was 2646.9 pg/mL. Bone marrow biopsy revealed some hemophagocytic histiocytes and a decreased number of megakaryocytes. T helper 1/T helper 2 (Th1/Th2) cytokine levels, including those of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IFN-γ, were quantitatively determined with a human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit II (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, United States) during the course of the disease (Figures 1 and 2). The results of the CBC comparison (Figure 3), C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, fibrinogen, triglyceride, and SF levels are shown in Table 1. The other laboratory findings are shown in Table 2.

| Testing date | Laboratory examination items | Results |

| September 26, 2022 | Nucleic acid detection of 13 pathogens from nasopharyngeal swab | Human Rhino Virus and Mycoplasma Pneumoniae were positive, and others were all negative |

| September 26, 2022 | T-cell spot of tuberculosis assay | Negative |

| September 26, 2022 | EBV antibodies | EBVCA-IgM was 1.26 U/mL, EBVCA-IgG was 10.9 U/mL, EBNA-IgG was more than 600 U/mL, EBEA-IgG was negative, and EBEA-IgM was 0.06 COI |

| September 26, 2022 | EBV-DNA | 0 copies/mL |

| September 28, 2022 | Blood culture | S. typhimurium was positive |

| September 30, 2022 | Widal test | FDSO, FDSH, FDSA, FDSB, and FDSC were all less than 1:40 |

| October 1, 2022 | Stool culture | Negative |

| October 1, 2022 | Cerebrospinal fluid culture | Negative |

| October 4, 2022 | Blood culture for the second time | Negative |

| October 7, 2022 | Urine culture | Negative |

| October 7, 2022 | Sputum culture | Negative |

| October 11, 2022 | Bone marrow culture | Negative |

| October 17, 2022 | Widal test for the second time | FDSO and FDSH were both 1:40, while FDSA, FDSB, and FDSC were less than 1:40 |

B-ultrasound of the abdomen and chest computed tomography showed no abnormalities.

The final diagnosis was sHLH due to S. typhimurium infection. The diagnosis of HLH was established on the basis of fever, cytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow; elevated levels of SF; and increased soluble CD25, which fulfilled more than five criteria. The diagnosis of S. typhimurium infection was confirmed by blood culture.

From September 25, 2022 to September 26, 2022, this patient received meropenem and linezolid anti-infection therapy. From September 26, 2022 to September 28, 2022, the patient received meropenem and high-dose methylprednisolone therapy (180 mg/d, body weight of 18.8 kg). From September 28, 2022 to October 11, 2022, the patient received cefoperazone/sulbactam as anti-infection therapy, and S. typhimurium was sensitive to the treatment. During the inpatient period, this boy experienced two episodes of shock, one on September 25, 2022 and one on October 3, 2022, during which time his blood pressure decreased to 78/40 mmHg and 72/44 mmHg, respectively. Both episodes of shock occurred after the patient developed a fever, and his body temperature eventually returned to normal. After antishock therapy, his vital signs stabilized. From October 11, 2022 to October 17, 2022, this patient received meropenem therapy again.

After careful evaluation, the patient did not receive HLH chemotherapy during the whole disease course and was discharged on October 17, 2022. During the nonhospitalization period, he was followed up by telephone for more than 1 year and recovered very well.

Currently, dexamethasone, etoposide, cyclosporine A, and ruxolitinib are the main choices for HLH treatment[15]. Reliable laboratory markers that can differentiate subtypes of HLH at an early stage would provide tremendous help for treatment. Several researchers have shown that elevated IL-10 levels are associated with a poor prognosis in HLH[16,17]. In this study, we examined 8 children infected with S. typhimurium, and only 1 of them fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for HLH. The IL-10 levels in this S. typhimurium-HLH patient and the 7 controls with S. typhimurium infection were lower than 10.0 pg/mL, while the levels of IL-10 in the 3 EBV-HLH patients were all greater than 10.0 pg/mL. In our clinical practice, different cytokine patterns for differentiating various HLH subtypes can be obtained within 5 h, and 88 patients with IFN-γ levels ≤ 225 pg/mL and a ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ ≤ 1.33 have the best outcome, showing that this subtype has the best outcome of all HLH subtypes[13], which was verified by this study.

There is no consensus on how to treat S. typhimurium-triggered sHLH, and early intervention is needed to improve outcomes in patients with HLH[18]. Most of the current research is empirical, and the decision-making process is relevant to the time point at which positive culture results are obtained and based on the clinician's experience. Several researchers have shown that antimicrobial and supportive treatment alone are effective[5,19-23]. However, many researchers have used both antimicrobial treatment and the HLH protocol to treat sHLH triggered by Salmonella infections[6,10,24]. In this study, after careful evaluation, our patient did not receive HLH chemotherapy during the whole disease course. After receiving meropenem, linezolid, and cefoperazone/sulbactam for anti-infection therapy combined with high-dose methylprednisolone therapy, the patient recovered very well.

This study had several limitations. First, it was impossible to precisely distinguish pHLH from sHLH, as this patient did not undergo pHLH-related gene examinations during the study period. Second, the 7 controls infected with S. typhimurium recovered well, and only some agreed to undergo a second recheck of their cytokines and CBC, which led to missing data. Finally, only 1 patient infected with S. typhimurium progressed to sHLH, and we could not perform a cohort analysis of specific cytokine patterns.

In summary, if a Salmonella-triggered sHLH patient has a ratio of IL-10 to IFN-γ ≤ 1.33, an IL-10 concentration ≤ 10.0 pg/mL, and/or an IFN-γ concentration ≤ 225 pg/mL at admission, early antimicrobial and supportive treatment may be sufficient. Eight weeks of dexamethasone treatment and the HLH-94/2004 protocol are not necessary under these conditions.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Polat SE, Turkey S-Editor: Liu H L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3601] [Article Influence: 200.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kanegane H, Noguchi A, Yamada Y, Yasumi T. Rare diseases presenting with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Int. 2023;65:e15516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Konishi S, Ono R, Tanaka M, Imadome KI, Nakazawa Y, Kanegane H, Hasegawa D. Cytokine-based disease monitoring in refractory HLH with primary EBV infection. Pediatr Int. 2023;65:e15590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chevalier K, Schmidt J, Coppo P, Galicier L, Noël N, Lambotte O. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Associated With Cytomegalovirus Infection: 5 Cases and a Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Arora N, Singla N, Jain A, Sharma P, Sharma N. Secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) triggered by Salmonella typhi. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98:e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Şahin Yaşar A, Karaman K, Geylan H, Çetin M, Güven B, Öner AF. Typhoid Fever Accompanied With Hematopoetic Lymphohistiocytosis and Rhabdomyolysis in a Refugee Child. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41:e233-e234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Badie F, Ghandali M, Tabatabaei SA, Safari M, Khorshidi A, Shayestehpour M, Mahjoubin-Tehran M, Morshedi K, Jalili A, Tajiknia V, Hamblin MR, Mirzaei H. Use of Salmonella Bacteria in Cancer Therapy: Direct, Drug Delivery and Combination Approaches. Front Oncol. 2021;11:624759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Galán JE. Salmonella Typhimurium and inflammation: a pathogen-centric affair. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19:716-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brown DE, McCoy MW, Pilonieta MC, Nix RN, Detweiler CS. Chronic murine typhoid fever is a natural model of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iwasaki T, Hara H, Takahashi-Igari M, Matsuda Y, Imai H. Probable hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis by extensively drug-resistant Salmonella Typhi. Pediatr Int. 2022;64:e14695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cron RQ, Goyal G, Chatham WW. Cytokine Storm Syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:321-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu XJ, Tang YM, Song H, Yang SL, Xu WQ, Zhao N, Shi SW, Shen HP, Mao JQ, Zhang LY, Pan BH. Diagnostic accuracy of a specific cytokine pattern in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children. J Pediatr. 2012;160:984-90.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xu XJ, Luo ZB, Song H, Xu WQ, Henter JI, Zhao N, Wu MH, Tang YM. Simple Evaluation of Clinical Situation and Subtypes of Pediatric Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis by Cytokine Patterns. Front Immunol. 2022;13:850443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Luo ZB, Chen YY, Xu XJ, Zhao N, Tang YM. Prognostic factors of early death in children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cytokine. 2017;97:80-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yan WL, Yang SL, Zhao FY, Xu XJ. Ruxolitinib is an alternative to etoposide for patient with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicated by acute renal injury: A case report. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022;28:222-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hao L, Ren J, Zhu Y, Ma Y, Pan J, Yang L. Elevated Interleukin-10 Levels Are Associated with Low Platelet Count and Poor Prognosis in 90 Adult Patients with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2023;184:400-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou Y, Kong F, Wang S, Yu M, Xu Y, Kang J, Tu S, Li F. Increased levels of serum interleukin-10 are associated with poor outcome in adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rubio-Perez J, Rodríguez-Perez ÁR, Díaz-Blázquez M, Moreno-García V, Dómine-Gómez M. Treatment-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to atezolizumab: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Uribe-Londono J, Castano-Jaramillo LM, Penagos-Tascon L, Restrepo-Gouzy A, Escobar-Gonzalez AF. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis Associated with Salmonella typhi Infection in a Child: A Case Report with Review of Literature. Case Rep Pediatr. 2018;2018:6236270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Çamlar SA, Kır M, Aydoğan C, Bengoa ŞY, Türkmen MA, Soylu A, Kavukçu S. Salmonella glomerulonephritis and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in an adolescent. Turk Pediatri Ars. 2016;51:173-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Caksen H, Akbayram S, Oner AF, Kösem M, Tuncer O, Ataş B, Odabaş D. A case of typhoid fever associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:321-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abbas A, Raza M, Majid A, Khalid Y, Bin Waqar SH. Infection-associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: An Unusual Clinical Masquerader. Cureus. 2018;10:e2472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Non LR, Patel R, Esmaeeli A, Despotovic V. Typhoid Fever Complicated by Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Rhabdomyolysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:1068-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dange NS, Sawant V, Dash L, Kondekar AS. A Rare Case of Salmonella meningitis and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2021;13:100-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |