Published online Mar 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1634

Peer-review started: October 20, 2023

First decision: January 25, 2024

Revised: February 3, 2024

Accepted: March 1, 2024

Article in press: March 1, 2024

Published online: March 26, 2024

Processing time: 157 Days and 7.1 Hours

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) are the most commonly used anticoagulants during pregnancy. It is considered to be the drug of choice due to its safety in not crossing placenta. Considering the beneficial effect in the impro

Herein we present a case series of three pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia on LMWH therapy during pregnancy. All the cases experienced catastrophic hemorrhagic events. After reviewing the twenty-one meta-analyses, the bleeding risk related with LMWH seems ignorable. Only one study analyzed the bleeding risk of LMWH and found a significantly higher risk of developing PPH in women receiving LMWH. Other studies reported minor bleeding risks, none of these were serious enough to stop LMWH treatment. Possibilities of bleeding either from uterus or from intrabdominal organs in preeclampsia patients on LMWH therapy should not be ignored. Intensive management of blood pressure even after delivery and homeostasis suture in surgery are crucial.

Consideration should be given to the balance between benefits and risks of LMWH in patients with preeclampsia.

Core Tip: Benefits and risks of low molecular weight heparins in pregnant patients diagnosed with preeclampsia should be carefully assessed. Strict control of blood pressure is needed to prevent further bleeding events.

- Citation: Shan D, Li T, Tan X, Hu YY. Low-molecular-weight heparin and preeclampsia — does the sword cut both ways? Three case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(9): 1634-1643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i9/1634.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1634

Due to its safety in not crossing the placental-fetal barrier, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is widely used in several placenta-mediated complications[1-4]. Many randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses regarding the improving function in placental micro-cocirculation of LMWH were conducted. However, heterogeneities in participant recruitment and difference in underlying physiopathological mechanisms of these placenta-mediated pregnancy complications contributed to controversial results. Most studies reported that LMWH is the anticoagulant of choice in pregnancy because of its favorable maternal safety profiles[5]. The safety parameters in long-term application of LMWH during pregnancy still needs to be considered. The safety parameters of LMWH including bleeding risk, allergy, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, or heparin-induced osteoporosis were seldomly summarized. Especially the bleeding risk associated with LMWH, which might be seriously underestimated. The bleeding risk in pregnant women using LMWH is still a subject of debate.

Most studies on LMWH application in pregnant women reported ignorable bleeding risks[6-9]. However, in patients with preeclampsia, a population with high risk of postpartum hemorrhage, the information on bleeding risk related with LMWH was insufficiently evaluated. In spite, previous studies implied LMWH was an ideal treatment by indicating the efficacy of LMWH in preventing the development of preeclampsia and improving pregnancy outcomes. To illustrate the bleeding risk related with LMWH therapy in patients with preeclampsia, herein, we report three cases and review the literature.

Case 1: Case 1 was a 34-year-old pregnant woman with a singleton fetus. She had high blood pressure for more than one month.

Case 2: Case 2 was a 36-year-old woman with a singleton fetus. She had high blood pressure and proteinuria for 3 wk.

Case 3: Case 3 was a 38-year-old woman diagnosed with preeclampsia. She was delivered by CS 5 d before and huge hematoma formation was found 2 d before.

Case 1: She was diagnosed with preeclampsia at 28th gestational week at local hospital and was admitted to our hospital due to poorly controlled blood pressure on 29th gestational week.

Case 2: She had regular antenatal care and was admitted to our hospital at 28 gestational weeks. Her blood pressure was controlled but she was still presented with severe proteinuria and elevated liver enzymes.

Case 3: She was transferred to our hospital five days after CS because of uncontrolled blood pressure and huge hematoma formation in the abdominal wall. She had irregular antenatal care at a local hospital and emergency CS was performed by the local hospital at 36th gestational week due to the presentation of severe headache and uncontrolled blood pressure. Antihypertensive drugs and LWMH was prescribed after CS in the local hospital. She was discharged three days after CS, but she presented with aggressive abdominal pain one day before she was transferred to our hospital. The blood pressure was as high as 180/100 mmHg at admission.

Case 1: She was diagnosed with hypertension in her previous pregnancy 3 years ago.

Case 2: There was no significant past history.

Case 3: There was no significant past history.

Case 1: There was no significant personal or family history.

Case 2: There was no significant personal or family history.

Case 3: Her sister was diagnosed with preeclampsia 2 years before during pregnancy.

Case 1: On physical examination, both of the patient’s lower extremities showed severe pitting edema.

Case 2: On physical examination, the left leg showed mild edema and the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Case 3: On physical examination, the patient had an anemic appearance, but the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

Case 1: The patient had hypoproteinemia. The plasma albumin was 28 g/L.

Case 2: The antinuclear antibodies, anti-nucleosome antibodies, anti-SSA antibodies, anti-Ro52 antibodies and anti-β2-glycoprotein antibodies were positive. Suspicion of obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome (OAPS) and Sjogren's syndrome were made after consultation by rheumatologic doctors.

Case 3: Laboratory findings revealed hypochromic anemia with hemoglobin level of 7.1 g/dL.

Case 1: The ultrasonography revealed intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and elevated umbilical artery flow velocity S/D value.

Case 2: The ultrasonography revealed the growth of the fetus was appropriate.

Case 3: Huge hematoma formation was found in the anterior abdominal wall (14.1 cm × 3.4 cm × 10.4 cm).

Severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction.

Severe preeclampsia, pregnancy complicated with immune disorders: OAPS and Sjogren's syndrome.

Severe preeclampsia, hematoma in abdominal wall.

Magnesium sulfate, antihypertensive therapy and LMWH were prescribed. At 31 gestational weeks, emergent CS was performed due to repeated non-response non-stress tests on fetal monitoring. The CS was successful with a baby of Apgar score 8-9-9 was born. However, hours after CS, her blood pressure declined progressively and the vital signs were not stable. Blood tests implied significantly decreased hemoglobin and abdominal paracentesis revealed hemoperitoneum. An emergent relaparotomy was performed. Large amount of fresh blood with clots were found in the abdomen (uncoagulable blood 1660 mL, blood clots 670 g). Bleeding was found in a small mesenteric artery. After evacuation of blood clots and hemostasis suture, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and then the general ward.

Antihypertensive therapy, hepatoprotective treatments, immune regulation and LMWH were given as the rheumatologic doctor suggested. At 32 gestational weeks, she had upper abdominal pain and vomiting after an unhygienic diet. Acute gastroenteritis was first suspected. Symptomatic and supportive treatment was given but the symptoms were not relieved. She had uncontrolled vomiting and the upper abdominal pain was aggressive. Abdominal ultrasound revealed large amount of ascites which emerged in short time. Emergent CS was performed. A female fetus with an Apgar score 3-6-8-9 was born. Large amounts of blood clots accumulated in the pelvic cavity, spleen and liver area. A small rupture with bleeding with a diameter of approximately 1cm was found in the Glisson’s capsule behind the gall bladder, which was repaired meticulously by a hepatobiliary surgeon during surgery.

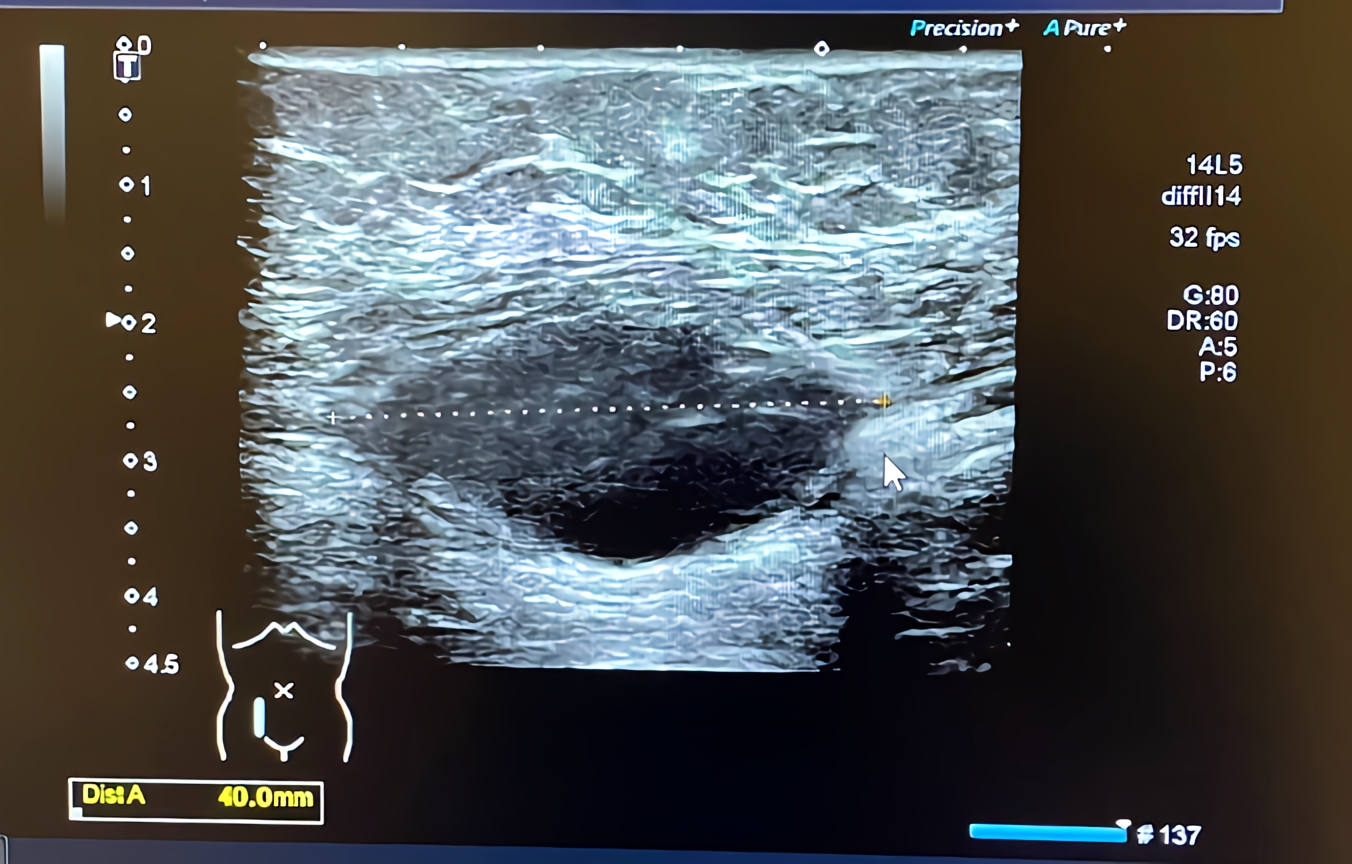

Intensive antihypertensive therapy was immediately administered. Intravenous antihypertensive medications were converted to oral antihypertensive medications progressively for three days after admission. Conservative treatments for hematoma with activating blood circulation herbs were applied after communication with the patients. The hematoma shrank to 10.1 cm × 3.0 cm × 8.9 cm at the 8 d after admission (Figure 1).

The patient recovered well and was discharged on day seven after CS.

The patient recovered well and was discharged on day eight after delivery.

The hematoma shrank to 6.0 cm x 2.0 cm x 3.0 cm two months later (Figure 2).

Low-molecular-weight heparin thromboprophylaxis recommendations differ across clinical practice guidelines for patients with preeclampsia[2-4,10,11]. Application of LMWH was not a common treatment option for patients at high risk for preeclampsia in the past decades in China. However, as the maternal mortality rate caused by pulmonary embolism increased, more attention was given to the LMWH prophylaxis and treatment in pregnant women in recent years. Lack of experience in LMWH usage sometimes put the obstetricians in a dilemma in balancing the benefits and risks. Here we reported three severe bleeding events in patients with preeclampsia receiving LMWH.

The hemorrhagic event caused by mesenteric artery was a rare event in case one. During pregnancy, the physiological changes of abdominal vessels during pregnancy included increased blood supply and hypostasis resulting from an enlarged uterus. Suspicion of spontaneous rupture in mesenteric artery is a possible and reasonable cause considering the uncontrolled blood pressure in this patient. Common tocolytic applications is an effective method for uterine bleeding, but functioned less in controlling bleeding from the mesenteric arteries. High blood pressure and LMWH significantly increased the possibility for aggressive intrabdominal bleeding. Case two of our report was diagnosed as acute gastroenteritis, with an initial history of unhygienic diet at first. Possibility of intrabdominal bleeding was considered due to the continuous presentation of vomiting with abdominal pain and large amount of ascites which emerged in a short time detected by ultrasound. Preeclampsia and sudden increased abdominal pressure during vomiting might lead to small rupture in Glisson’s capsule. With the application of LMWH, subsequent severe hemorrhage from liver, of which the blood supplementation significantly increased compared with that in non-pregnancies, put the patient in hypovolemic shock immediately. Although being a rare event in pregnant women, spontaneous bleeding from abdominal organ and large vessels was reported in pregnant women in the literature, especially in patients with preeclampsia[12-14]. It was reported that sub-capsular liver hematoma occurred in 1%–2% of patients with HELLP syndrome[13,14]. The presentation of hematoma might be nonspecific. Possible complaints of patients might be nausea and right upper quadrant discomfort. But in pregnant women, none of these symptoms are typical, this certainly would lead to the possibility of misdiagnosis. Huge hematoma formation in case 3 indicated the urgent needs for strict control of blood pressure even after delivery. Management of blood pressure is still crucial in postpartum patients. The uncontrolled blood pressure after the CS together with LMWH led to hematoma formation in the pregnant woman’s uncompacted abdominal wall in case three.

Due to its pharmacological properties in improving microcirculation, the efficacy of LMWH has been evaluated in several pregnancy related complications in recent decades. The review on LMWH application in patients with preeclampsia patients were not identified by searching Pubmed and Embase databases. However, we found several meta-analyses regarding the preventive and treatment effect of LMWH on antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL), venous thromboembolism (VTE), preeclampsia, IUGR and small for gestational age (SGA). A total of 21 studies were summarized (Table 1)[6-9,15-31]. However, by analyzing these researches, we found limited information on bleeding risk either antenatally or postnatally. Only one study by Sirico et al[28] analysed thromboprophylaxis with LMWH in women during the third trimester of pregnancy. Some studies reported increased risk in minor bleeding[18,24,25,31]. Majority of the meta-analyses found no significant difference in bleeding events rate in LMWH group compared with LDA or placebo. No studies reported hepatic hematoma or major bleeding events from intrabdominal vessel.

| Ref. | Year | Included population | Number of studies included | Comparison | Efficacy | Safety: Bleeding risk |

| Areia et al[15] | 2016 | Women with hereditary thrombophilia | 4 studies; 222 participants | LMWH + LDA vs LDA | No difference was found with regard to live births rate in LMWH + LDA group versus LDA group | Not reported |

| Bettiol et al[16] | 2021 | Pregnant women at high risk of FGR, defined as those with at least one of the follow: history of FGR in the previous pregnancies, history of late pregnancy loss or recurrent early pregnancy loss, hypertensive disorders, inherited or acquired thrombophilia | 30 studies; 4326 participants | LMWH/UFH/LDA/other antiplatelet agents vs control | Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), alone or associated with low-dose aspirin (LDA), appeared more efficacious than controls in preventing FGR | No treatment was associated with an increased risk of bleeding |

| Cruz-Lemini et al[6] | 2022 | Patients who had any known risk factors for developing PE, and medical history including thrombophilia, autoimmune diseases, and chronic hypertension | 15 studies; 2795 participants | LMWH ± LDA vs control; LMWH vs LDA | In high-risk women, LMWH was associated with a reduction in the development of PE, SGA and perinatal death | No statistically significant difference in bleeding was found between LMWH and control, regardless of whether or not LMWH was combined with aspirin |

| Dias et al[17] | 2021 | Women with a history of recurrent abortion without an identified cause | 7 studies 1855 participants | LMWH vs control | The LMWH group had a higher incidence of continuous pregnancy after the 20th week of gestation | There was no statistically significant difference between the groups on hemorrhagic events |

| Guerby et al[18] | 2021 | Pregnant women with APS | 13 studies; 1916 participants | LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs LDA/IVIG | Heparin and LMWH, associated or not to aspirin, significantly increased the rate of live birth and decreased the rate of preeclampsia | Treatment with heparin and LMWH was associated with a significant increase in minor bleeding (bruises, epistaxis) (RR 2.58, 95%CI 1.03-6.43) |

| Hamulyák et al[19] | 2020 | Women with persistent (on two separate occasions) aPL, either lupus anticoagulant (LAC), anticardiolipin (aCL) or aβ(2)-glycoprotein-I antibodies [aβ(2)GPI] or a combination, and recurrent pregnancy loss | 11 studies; 1672 participants | LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs LDA; LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs control | Heparin plus aspirin may increase the number of live births. Heparin plus aspirin may reduce the risk of pregnancy loss. We are uncertain if heparin plus aspirin has any effect on the risk of pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery or intrauterine growth restriction, compared with aspirin alone | We are very uncertain if heparin plus aspirin has any effect on bleeding in the mother compared with aspirin alone |

| Intzes et al[20] | 2021 | Women with or without hereditary thrombophilia and recurrent pregnancy loss | 12 studies; 2298 participants | LMWH vs control | LMWH on live birth rates is not significant in women with or without thrombophilia | Not reported |

| Jacobson et al[21] | 2020 | Pregnant women receiving enoxaparin | 24 studies | Enoxaparin vs control | In patients with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss, the rates of pregnancy loss were significantly lower for enoxaparin compared to untreated controls | Bleeding events were non-significantly compared between enoxaparin with untreated controls or aspirin |

| Jiang et al[9] | 2021 | Pregnant women with recurrent pregnancy loss | 8 studies; 1854 participants | LMWH vs control | LMWH had significantly improved live births rates and reduced miscarriage rates | Receiving LMWHs had no substantial impact on bleeding episodes |

| Liu et al[8] | 2021 | Patients with recurrent pregnant loss | 6 studies; 1034 participants | Enoxaparin vs control | Enoxaparin has no obvious impact on live births, abortion rate, birth weight, preterm delivery and preeclampsia | Enoxaparin has no obvious impact on postpartum hemorrhage |

| Liu et al[22] | 2020 | Naturally pregnant women aged 18 or older with a diagnosis of recurrent pregnancy loss and APS | 12 studies; 1910 participants | LMWH/UFH + LDA vs control | LMWH plus aspirin had a higher live birth rate than aspirin alone, UFH plus aspirin showed a higher live birth rate than aspirin alone | Not reported |

| Lu et al[23] | 2019 | Women with APS and recurrent spontaneous abortion | 19 studies; 1251 participants | LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs LDA; LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs control | With respect to live birth, it was remarkably improved in aspirin plus heparin or heparin alone group compared with aspirin alone group. Low-dose aspirin plus heparin therapy was significant reduce the risk of preeclampsia | Aspirin plus heparin therapy did not significantly increase minor bleeding risk |

| Mastrolia et al[24] | 2016 | Pregnant women at risk for developing preeclampsia, IUGR, placental abruption, spontaneous preterm delivery and fetal death | 5 studies; 403 participants | LMWH vs control | The overall use of LMWH was associated with a risk reduction for preeclampsia and IUGR | Minor bleeding complication in two patients in LMWH group |

| Middleton et al[25] | 2021 | Women who were pregnant or had given birth in the previous six weeks, at increased risk of VTE, were included. Women at increased risk were those having/following a caesarean section, with an acquired or inherited thrombophilia, and/or other risk factors for VTE | 29 studies; 3839 participants | LMWH/UFH vs control; LMWH vs UFH | Evidence was very uncertain for antenatal (± postnatal) prophylaxis for prevent thromboembolic event (PE and DVT) | Evidence was very uncertain on adverse effects sufficient to stop treatment caused by bleeding. Only one study reported adverse effects sufficient to stop treatment caused by bleeding during LMWH treatment (3 patients with placenta previa) |

| Roberge et al[26] | 2016 | Women with previous history of PE | 8 studies; 885 participants | LMWH/UFH ± LDA vs LDA | In women with previous history of PE, treatment with LMWH and aspirin, compared to aspirin alone, was associated with a significant reduction in PE and birth of SGA neonates | Not reported |

| Rodger et al[27] | 2016 | Women pregnant at the time of the study with a history of previous pregnancy that had been complicated by one or more of the following: pre-eclampsia, placental abruption, birth of an SGA neonate, pregnancy loss after 16 wk’ gestation, or two losses after 12 wk’ gestation | 8 studies; 963 participants | LMWH vs control | LMWH did not significantly reduce the risk of recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications. In subgroup analyses, LMWH in multicenter trials reduced the placenta-mediated pregnancy complications in women with previous abruption | In the antepartum period, there is no significant difference in risk for major bleeding. In the peripartum and postpartum periods, the incidence of major bleeding did not differ between the treatment and control groups |

| Sirico et al[28] | 2019 | Women who underwent thromboprophylaxis with LMWH during the third trimester of pregnancy | 8 studies; 22162 participants | LMWH vs control | Not reported | Women treated with LMWH had an higher risk of PPH (RR 1.45, 95%CI 1.02 to 2.05) compared to controls. There was no difference in mean of blood loss at delivery and in risk of blood transfusion at delivery |

| Urban et al[7] | 2021 | Patients affected by obstetric APS, with or without thrombotic APS | 8 studies; 395 participants | UFH/LMWH + LDA vs LDA; LMWH + LDA vs UFH + LDA; LDA + UFH + IVIg vs LDA + UFH | No difference among treatments emerged in terms of FGR prevention, but estimates were largely imprecise | No treatment was associated with an increased risk of bleeding |

| Wang et al[29] | 2020 | Women with subsequent pregnancies who previously had early onset or severe PE | 7 studies; 1035 participants | LMWH vs LDA; LMWH vs control | There were risk reductions on PE rate, small-for-gestational-age neonate rate. LMWH led to an increase in gestational length and neonatal weight | Not reported |

| Yan et al[30] | 2022 | Patients with unexplained recurrent miscarriage with negative antiphospholipid antibodies | 7 studies; 1849 participants | LMWH ± LDA vs control | No substantial influence on miscarriage rate and the occurrence rate of pre-eclampsia | Not reported |

| Yang et al[31] | 2018 | Women undergoing IVF/ICSI | 5 studies; 935 participants | LMWH vs control | No significant differences for live birth rate, clinical pregnancy rate and miscarriage rate were found between the low-molecular-weight heparin and control groups | One study reported five cases of minor vaginal bleeding in women receiving LMWH treatment, but not serious enough to stop the use of LMWH |

Three meta-analyses focused on patients with preeclampsia[6,26,29]. These studies reported consistencies of the beneficial effect on reduction of PE rate from LMWH treatment. The reduction on SGA development were testified and neonatal birthweight were also improved. However, only one study reported non-significant difference in bleeding risk of LMWH in patients with preeclampsia[6]. The bleeding risk of LMWH was not reported in other two studies.

Similar with our reported cases, Sirico et. al reported augmented risk of bleeding[28]. They included eight randomized controlled trails and indicated that women who received LMWH during pregnancy had a significantly higher risk of developing post-partum hemorrhage (PPH). No difference was found in the mean blood loss during delivery or risk for blood transfusion. Except for PPH, serious antenatal bleeding in patients with placenta previa was also reported as an important reason to quite LMWH treatment[25]. Despite recognizing this as a small probability event, the safety of LMWH in patients with high risk of antenatal hemorrhage should be evaluated. For minor bleeding events, one study reported increased risk in LMWH group from nine trials. The risk for bruises and epistaxis was 2 times higher in patients in heparin group[18]. Bloody vaginal discharge, minor vaginal bleeding and subcutaneous hemorrhage from injection point were also reported. However, none of these symptoms were serious. None of these minor bleeding events stopped patients from LMWH treatment.

Notably, the indication of LMWH application in these three patients worth our serious consideration. Due to its advantages in the safety to the fetus and less possibility of causing osteopenia, LMWH is the recommended treatment in pregnant women over unfractionated heparin (UFH)[32]. In our three cases, both of these patients were treated with a prophylaxis dose of LMWH. However, since LMWH did not have direct antihypertensive function, application of LMWH in PE patients renders more consideration. Despite its benefiting effects in improving microcirculation, LMWH is not included in the treatment strategy of PE patients[33-35] and patients with IUGR risk factors[36-39] as suggested by many guidelines. In case 1 and case 3, the LMWH was prescribed in view of improving the microcirculation in preeclampsia patients. In case 2, LMWH was given due to the suspicion of immune disorders. OAPS was suspected in this case although the patient lack other diagnostic criteria. Whether or not LMWH could improve the pregnancy outcomes in patients with PE and IUGR is still in debate. From the meta-analyses we included, it seemed that the beneficial effect of LMWH in improving some key obstetric outcomes in pregnancies including birth live rates, pregnancy loss rates, SGA and IUGR still seemed controversial. The absence of effect of LMWH in these placenta-mediated pregnancy complications might reflect the multifactorial pathophysiology. The safety parameter of LMWH for the fetus has already been assessed, since it does not pass the placental barrier. The safety parameter of LMWH for the mothers was not adequately estimated. The association of anticoagulation with bleeding should still be postulated.

Bearing in mind the benefits and risks of LMWH in the treatment and prevention of preeclampsia, the application of LMWH should be reconsidered. In patients with preeclampsia and IUGR, LMWH was not included in the treatment strategy, but prophylaxis application of LMWH might have beneficial effect for improving microcirculations. However, the overall effect of improving pregnancy outcomes in these patients is still in debate. If prescribed, a planned labour was recommended with enough time interval from last dose of LMWH. In emergency situations, careful check and hemostasis procedures are crucial during CS. Careful management of blood pressure after delivery have key significance in preventing complications after delivery. Obstetricians should be remind of the elevated bleeding risk in patients with preeclampsia taking LMWH.

Pending further data to establish a balance between benefits and risks of LMWH in patients with preeclampsia, the cases in our report represented the nonnegligible bleeding risks during LMWH therapy. When patients presented signs suggestive of hemorrhage without vaginal bleeding, the possibility of intraabdominal hemorrhage should be taken into consideration. If conservative management is inadequate, exploratory laparotomy should be implemented.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Obstetrics & gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ait Addi R, Morocco S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). , Pacheco LD, Saade G, Metz TD. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #51: Thromboembolism prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B11-B17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: Thromboembolism in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e1-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Queensland Clinical Guidelines. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in pregnancy and the puerperium. Guideline MN20.9-V6-R25. Queensland Health. 2020. Available from: http://www.health.qld.gov.au/qcg. |

| 4. | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium (green-top guideline No.37a). 2015: 1-40. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/reducing-the-risk-of-thrombosis-and-embolism-during-pregnancy-and-the-puerperium-green-top-guideline-no-37a/. |

| 5. | Skeith L. Prevention and management of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: cutting through the practice variation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2021;2021:559-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cruz-Lemini M, Vázquez JC, Ullmo J, Llurba E. Low-molecular-weight heparin for prevention of preeclampsia and other placenta-mediated complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:S1126-S1144.e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Urban ML, Bettiol A, Mattioli I, Emmi G, Di Scala G, Avagliano L, Lombardi N, Crescioli G, Virgili G, Serena C, Mecacci F, Ravaldi C, Vannacci A, Silvestri E, Prisco D. Comparison of treatments for the prevention of fetal growth restriction in obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:1357-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu Y, Shan N, Yuan Y, Tan B, Che P, Qi H. The efficacy of enoxaparin for recurrent abortion: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;34:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jiang F, Hu X, Jiang K, Pi H, He Q, Chen X. The role of low molecular weight heparin on recurrent pregnancy loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ducloy-Bouthors AS, Baldini A, Abdul-Kadir R, Nizard J; ESA VTE Guidelines Task Force. European guidelines on perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: Surgery during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:130-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bates SM, Rajasekhar A, Middeldorp S, McLintock C, Rodger MA, James AH, Vazquez SR, Greer IA, Riva JJ, Bhatt M, Schwab N, Barrett D, LaHaye A, Rochwerg B. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: venous thromboembolism in the context of pregnancy. Blood Adv. 2018;2:3317-3359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Escobar Vidarte MF, Montes D, Pérez A, Loaiza-Osorio S, José Nieto Calvache A. Hepatic rupture associated with preeclampsia, report of three cases and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:2767-2773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCormick PA, Higgins M, McCormick CA, Nolan N, Docherty JR. Hepatic infarction, hematoma, and rupture in HELLP syndrome: support for a vasospastic hypothesis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:7942-7947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bradke D, Tran A, Ambarus T, Nazir M, Markowski M, Juusela A. Grade III subcapsular liver hematoma secondary to HELLP syndrome: A case report of conservative management. Case Rep Womens Health. 2020;25:e00169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Areia AL, Fonseca E, Areia M, Moura P. Low-molecular-weight heparin plus aspirin versus aspirin alone in pregnant women with hereditary thrombophilia to improve live birth rate: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bettiol A, Avagliano L, Lombardi N, Crescioli G, Emmi G, Urban ML, Virgili G, Ravaldi C, Vannacci A. Pharmacological Interventions for the Prevention of Fetal Growth Restriction: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110:189-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dias ATB, Modesto TB, Oliveira SA. Effectiveness of the use of Low Molecular Heparin in patients with repetition abortion history: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2021;25:10-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guerby P, Fillion A, O'Connor S, Bujold E. Heparin for preventing adverse obstetrical outcomes in pregnant women with antiphospholipid syndrome, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hamulyák EN, Scheres LJ, Marijnen MC, Goddijn M, Middeldorp S. Aspirin or heparin or both for improving pregnancy outcomes in women with persistent antiphospholipid antibodies and recurrent pregnancy loss. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;5:CD012852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Intzes S, Symeonidou M, Zagoridis K, Stamou M, Spanoudaki A, Spanoudakis E. Hold your needles in women with recurrent pregnancy losses with or without hereditary thrombophilia: Meta-analysis and review of the literature. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:101935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jacobson B, Rambiritch V, Paek D, Sayre T, Naidoo P, Shan J, Leisegang R. Safety and Efficacy of Enoxaparin in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Ther. 2020;37:27-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu X, Qiu Y, Yu ED, Xiang S, Meng R, Niu KF, Zhu H. Comparison of therapeutic interventions for recurrent pregnancy loss in association with antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;83:e13219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lu C, Liu Y, Jiang HL. Aspirin or heparin or both in the treatment of recurrent spontaneous abortion in women with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1299-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mastrolia SA, Novack L, Thachil J, Rabinovich A, Pikovsky O, Klaitman V, Loverro G, Erez O. LMWH in the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction in women without thrombophilia. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116:868-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Middleton P, Shepherd E, Gomersall JC. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for women at risk during pregnancy and the early postnatal period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3:CD001689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Roberge S, Demers S, Nicolaides KH, Bureau M, Côté S, Bujold E. Prevention of pre-eclampsia by low-molecular-weight heparin in addition to aspirin: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:548-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rodger MA, Gris JC, de Vries JIP, Martinelli I, Rey É, Schleussner E, Middeldorp S, Kaaja R, Langlois NJ, Ramsay T, Mallick R, Bates SM, Abheiden CNH, Perna A, Petroff D, de Jong P, van Hoorn ME, Bezemer PD, Mayhew AD; Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin for Placenta-Mediated Pregnancy Complications Study Group. Low-molecular-weight heparin and recurrent placenta-mediated pregnancy complications: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2016;388:2629-2641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sirico A, Saccone G, Maruotti GM, Grandone E, Sarno L, Berghella V, Zullo F, Martinelli P. Low molecular weight heparin use during pregnancy and risk of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1893-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang X, Gao H. Prevention of preeclampsia in high-risk patients with low-molecular-weight heparin: a meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:2202-2208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yan X, Wang D, Yan P, Li H. Low molecular weight heparin or LMWH plus aspirin in the treatment of unexplained recurrent miscarriage with negative antiphospholipid antibodies: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022;268:22-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yang XL, Chen F, Yang XY, Du GH, Xu Y. Efficacy of low-molecular-weight heparin on the outcomes of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection pregnancy in non-thrombophilic women: a meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2018;97:1061-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Saad A, Safarzadeh M, Shepherd M. Anticoagulation Regimens in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2023;50:241-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 530] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. In Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. London. 2019. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133. |

| 35. | Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K, McMahon LP, Morton M, North RA, Paech M, Said JM. SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:e1-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fetal Growth Restriction: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 227. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:e16-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lees CC, Stampalija T, Baschat A, da Silva Costa F, Ferrazzi E, Figueras F, Hecher K, Kingdom J, Poon LC, Salomon LJ, Unterscheider J. ISUOG Practice Guidelines: diagnosis and management of small-for-gestational-age fetus and fetal growth restriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56:298-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 90.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). , Martins JG, Biggio JR, Abuhamad A. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consult Series #52: Diagnosis and management of fetal growth restriction: (Replaces Clinical Guideline Number 3, April 2012). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:B2-B17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Investigation and Management of the Small–for–Gestational–Age Fetus. Green-top guideline No. 31. RCOG 2014. Available from: https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/small-for-gestational-age-fetus-investigation-and-management-green-top-guideline-no-31/. |