Published online Mar 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1555

Peer-review started: December 29, 2023

First decision: January 20, 2024

Revised: January 26, 2024

Accepted: February 27, 2024

Article in press: February 27, 2024

Published online: March 26, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 20.6 Hours

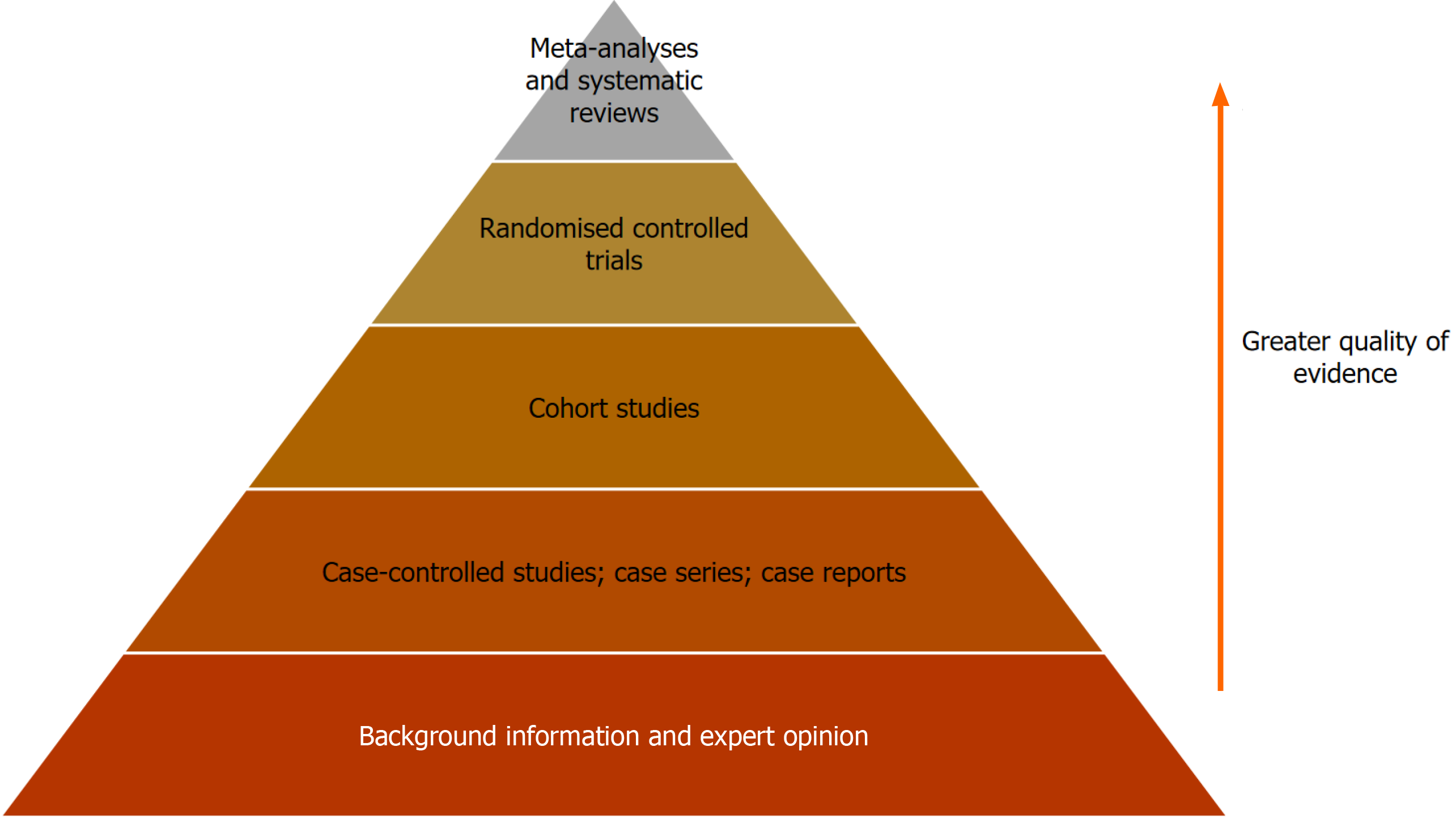

Evidence-based practice (EBP) has been the gold standard in healthcare for nearly three centuries and aims to assist physicians in providing the safest and most effective healthcare for their patients. The well-established hierarchy of evidence lists systematic reviews and meta-analyses at the top however these methodologies are not always appropriate or possible and in these instances case-control studies, case series and case reports are utilised to support EBP. Case-control studies allow simultaneous study of multiple risk factors and can be performed rapidly and relatively cheaply. A recent example was during the Coronavirus pandemic where case-control studies were used to assess the efficacy of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers. Case series and case reports also play a role in EBP and are particularly useful to study rare diseases such as in

Core Tip: Evidence-based practice is used by physicians to select the optimum treatment for their patients. The hierarchy of evidence lists systematic reviews and meta-analyses as the highest quality of evidence however this is not always appropriate or possible which is when clinical cases, either as case-control studies or case reports, can be utilised. This paper will look at the strength and weaknesses of these methodologies and use recent examples to demonstrate the impact they can have on clinical practice.

- Citation: Colwill M, Baillie S, Pollok R, Poullis A. Using clinical cases to guide healthcare. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(9): 1555-1559

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i9/1555.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i9.1555

James Lind, a Scottish physician in the 18th century, is considered to have conducted the first recorded clinical trial in the 1740s when he selected 12 sailors with scurvy and divided them into six cohorts of two to whom he administered various contemporary treatments and noted the greatest improvement in those given lemons and oranges[1]. Even though it took 50 years for the British navy to make lemon juice compulsory for sailor’s diets because of the cost, the age of evidence-based medicine had begun.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) has dramatically changed since the 1700s and is now well recognised as key to pro

Whilst perhaps ideally all clinical decisions would have the backing of a meta-analysis or systematic review, there are many occasions where there simply is not the data available. For example when bringing a new therapy to market the most appropriate level of evidence is a randomised double-blinded placebo control trial (RCT) and this, whilst expensive and sometimes ethically problematic, provides the strongest evidence of a cause and effect relationship and is therefore the gold-standard for clinical trials and often a pre-requisite to achieve regulator approval. Similarly, in rare disease (sometimes called orphan diseases) there are not enough cases to be able to power a study, apply statistical analysis and determine the validity of a hypothesis. This is where case-control studies and case reports can be useful to allow heal

These are retrospective observational studies which involve the identification of cases and researchers then constructing a control group with similar characteristics. Historical factors are then identified to see if these exposures are more fre

Recent examples of the utility of these studies were during the initial phases of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. A study in Thailand comparing 211 coronavirus infections with 839 controls aimed to assess the efficacy of personal pro

Whilst there were some undoubted weaknesses in these studies, such as bias and lack of clear accounting for con

Case reports and case series are descriptive studies which are used to present the clinical history and progress of patients in the ‘real-world’. Case reports consist of 3 or fewer patients whilst case series tend to have multiple patients and offer further qualitative methodology. The observational nature of these studies means that they are cheap and relatively quick to perform but perhaps their greatest utility is in rare diseases or treatments[7] where the lack of available patients makes other research methodologies impossible.

An example is with regards to inflammatory bowel disease in trans-gender or gender non-conforming patients (IBD-TGNC). Research using census data has identified there are approximately 2000 IBD-TGNC patients in the United King

Case reports can also be used to generate hypotheses which, once disseminated to the wider medical community, can be further tested and a body of evidence developed. One example of this, published in the Lancet in 1983, is that of an infant who required multiple blood transfusions but went on to die at 17 months of opportunistic infections and was found to have an acquired immunodeficiency. The authors hypothesised this may be due to a blood borne virus, later identified as the human immunodeficiency virus, and led to an unprecedented research effort which continues to this day.

Whilst advantageous in certain settings, one of the main areas of concern is regarding patient identity particularly in rare pathology. Even though the publication will anonymise some elements of the data, the description of very rare phenomena may be sufficient to de-anonymise individuals. Therefore, safeguarding measures should be in place as well as open communication with the patients described in these case reports to ensure explicit informed consent is gained and various institutions have published guidance regarding this[10].

Other disadvantages of these studies are that they are uncontrolled, suffer from selection bias and generally have an insufficient follow-up period. There can also be difficulty in using these studies for scientific research given that the cases described may not be easily generalisable to the wider population. However, whilst their value remains a matter for sci

Case series were historically the backbone of medical literature and whilst their importance has become smaller, they continue to be an important part of research.

They are particularly useful for novel observations and publishing early signals can inform the medical community to be vigilant for similar cases. This was recently demonstrated in a series published in January 2020 regarding patients infected with coronavirus in Wuhan[11]. Case series can also be useful for testing novel treatments, demonstrated by an IBD study in 2018 which wanted to provide preliminary data on dual biologic therapy (DBT)[12]. Through a case series of four patients they were able to show safety and efficacy signals which led to larger studies and DBT is now considered an effective option for difficult to treat disease[13].

These series, similar to case reports, can also be useful for studying rarer pathology. A 2021 study by Phillips et al[14] used a case series of 15 patients across 8 different centres to investigate factors associated with intestinal lymphoma in the context of IBD, a rare pathology believed to be related to thiopurine and anti-TNF use. As well as helping to identify risk factors, such as male sex and thiopurine use in two-thirds of their cohort, the series also helped to address the challenging clinical conundrum regarding the safety of restarting immunosuppressive therapy in patients with a history of intestinal lymphoma.

Case series can be published quickly, a particular strength with regards to the coronavirus series described above, and are cheap to develop compared to other methodologies such as RCTs which can cost in excess of $100000 per patient enrolled[15]. However, their use as a research modality also suffers from similar disadvantages as described for case reports particularly a lack of control, selection bias and difficulty around generalising to the wider population. Never

Whilst they are the lowest ranked strata of research in EBP with clear disadvantages, case reports and case studies still represent an important and useful modality that are relatively quick and cost-effective to produce. When utilised in the appropriate context, these studies continue to have a significant impact upon clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: British Society of Gastroenterology, BSG60672.

Specialty type: Methodology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gu GL, China S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Collier R. Legumes, lemons and streptomycin: a short history of the clinical trial. CMAJ. 2009;180:23-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Connor L, Dean J, McNett M, Tydings DM, Shrout A, Gorsuch PF, Hole A, Moore L, Brown R, Melnyk BM, Gallagher-Ford L. Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2023;20:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leufer T, Cleary-Holdforth J. Evidence-based practice: improving patient outcomes. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M, Alahdab F. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med. 2016;21:125-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 469] [Cited by in RCA: 730] [Article Influence: 81.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Doung-Ngern P, Suphanchaimat R, Panjangampatthana A, Janekrongtham C, Ruampoom D, Daochaeng N, Eungkanit N, Pisitpayat N, Srisong N, Yasopa O, Plernprom P, Promduangsi P, Kumphon P, Suangtho P, Watakulsin P, Chaiya S, Kripattanapong S, Chantian T, Bloss E, Namwat C, Limmathurotsakul D. Case-Control Study of Use of Personal Protective Measures and Risk for SARS-CoV 2 Infection, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2607-2616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rodriguez-Lopez M, Parra B, Vergara E, Rey L, Salcedo M, Arturo G, Alarcon L, Holguin J, Osorio L. A case-control study of factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers in Colombia. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Torres-Duque CA, Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Case series: an essential study design to build knowledge and pose hypotheses for rare and new diseases. J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46:e20200389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Colwill M, Patel K, Poullis A. Inflammatory bowel disease in the LGBTIQ+ population: estimates of prevalence in England & Wales and the implication for services. United European Gastroenterol J. 2023;11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Hennigan TW, Theodorou NA. Ulcerative colitis and bleeding from a colonic vaginoplasty. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:418-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yale University. Resource Documents and Guidance | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Available from: https://hipaa.yale.edu/resources/resource-documents-and-guidance. |

| 11. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30121] [Article Influence: 6024.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Mao EJ, Lewin S, Terdiman JP, Beck K. Safety of dual biological therapy in Crohn's disease: a case series of vedolizumab in combination with other biologics. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2018;5:e000243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCormack MD, Wahedna NA, Aldulaimi D, Hawker P. Emerging role of dual biologic therapy for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:2621-2630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Corrigendum to: ECCO CONFER Investigators, Diagnosis and Outcome of Extranodal Primary Intestinal Lymphoma in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An ECCO CONFER Case Series. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Speich B, von Niederhäusern B, Schur N, Hemkens LG, Fürst T, Bhatnagar N, Alturki R, Agarwal A, Kasenda B, Pauli-Magnus C, Schwenkglenks M, Briel M; MAking Randomized Trials Affordable (MARTA) Group. Systematic review on costs and resource use of randomized clinical trials shows a lack of transparent and comprehensive data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;96:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |