Published online Mar 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i7.1305

Peer-review started: October 9, 2023

First decision: January 12, 2024

Revised: January 25, 2024

Accepted: February 6, 2024

Article in press: February 6, 2024

Published online: March 6, 2024

Processing time: 143 Days and 21.2 Hours

Cervical necrotizing fasciitis (CNF) is a rare, aggressive form of deep neck space infection with significant morbidity and mortality rates. Serial surgical debri

We report two cases in which the keystone flap (KF) was used for CNF defect coverage: Case 1, an 85-year-old patient with CNF in the anterior neck, and Case 2, a 54-year-old patient with CNF in the posterior neck. Both patients received empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy and underwent serial debridement, enabling adequate wound preparation and stabilization. The final defect size measured 5.5 cm × 12 cm in Case 1 and 6 cm × 11 cm in Case 2. For defect coverage, we employed an 8 cm × 19 cm type II KF based on perforators from the superior thyroid artery in Case 1 and a 9 cm × 18 cm type II KF based on perforators from the transverse cervical artery in Case 2. Both flaps showed complete survival. No postoperative complications occurred in both cases, and favorable outcomes were observed at 7- and 6-month follow-ups in case 1 and 2, respectively.

We effectively treated CNF-associated defects using the KF technique; KF is viable for covering CNF defects in carefully selected cases.

Core Tip: Cervical necrotizing fasciitis (CNF) is associated with rapid tissue destruction and mortality; hence, early diagnosis and prompt treatment are necessary. However, serial debridement of necrotic tissues often leads to defects that complicate reconstructions, necessitating the selection of an appropriate reconstruction method. This study, therefore, reports our experiences using the modified keystone flap (KF) technique for CNF defect coverage in two patients. The modified KF technique may serve as an effective reconstructive option for neck defects, owing to its reliable and favorable outcomes in selected cases with small- to moderate-sized defects.

- Citation: Cho W, Jang EA, Kim KN. Reconstruction of cervical necrotizing fasciitis defect with the modified keystone flap technique: Two case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(7): 1305-1312

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i7/1305.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i7.1305

Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a relatively uncommon but life-threatening soft tissue infection with significant mortality, even if optimal treatment is administered[1-6]. Cervical NF (CNF) is a severe soft tissue infection characterized by rapidly progressive necrosis of the fascia and subcutaneous tissues along cervical fascial planes, predominantly affecting the face and neck areas[1-4,7]. This condition can lead to extensive gangrene and abscess formation in the deep neck space[1-7]. Because of the rapid tissue destruction associated with CNF, early diagnosis and prompt management are crucial. Interventions such as securing the airway, administering empirical broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and perfor

The indispensable serial debridement of necrotic tissues often results in defects that present challenging reconstruction scenarios. To address these issues, surgeons must carefully select appropriate reconstructive options based on the size and depth of the defects[8]. Skin grafts may be considered for superficial defects, whereas local flaps are suitable for small- to moderate-sized defects with exposed underlying structures[8,9]. In cases with extensive complex defects, free flaps are often preferred; however, all decisions are made on a case-by-case basis[8,9]. In this context, we report our experiences with the modified keystone flap (KF) technique for CNF defect coverage in two cases. We theorize that this technique can be a valuable option in the management of such challenging scenarios.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konyang University Hospital (approval number: 2020-07-015-01). All research procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Case 1: An 85-year-old man presented with CNF in the anterior neck area.

Case 2: A 54-year-old man presented with CNF in the posterior neck area.

Case 1: The patient exhibited rapidly progressive swelling and inflammation in the right cheek and neck following a tooth extraction.

Case 2: The condition rapidly progressed, following the occurrence of a tiny folliculitis on the posterior neck area.

Case 1: The patient reported multiple comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic renal failure.

Case 2: The patient had several underlying conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal failure.

There was no family history of similar diseases.

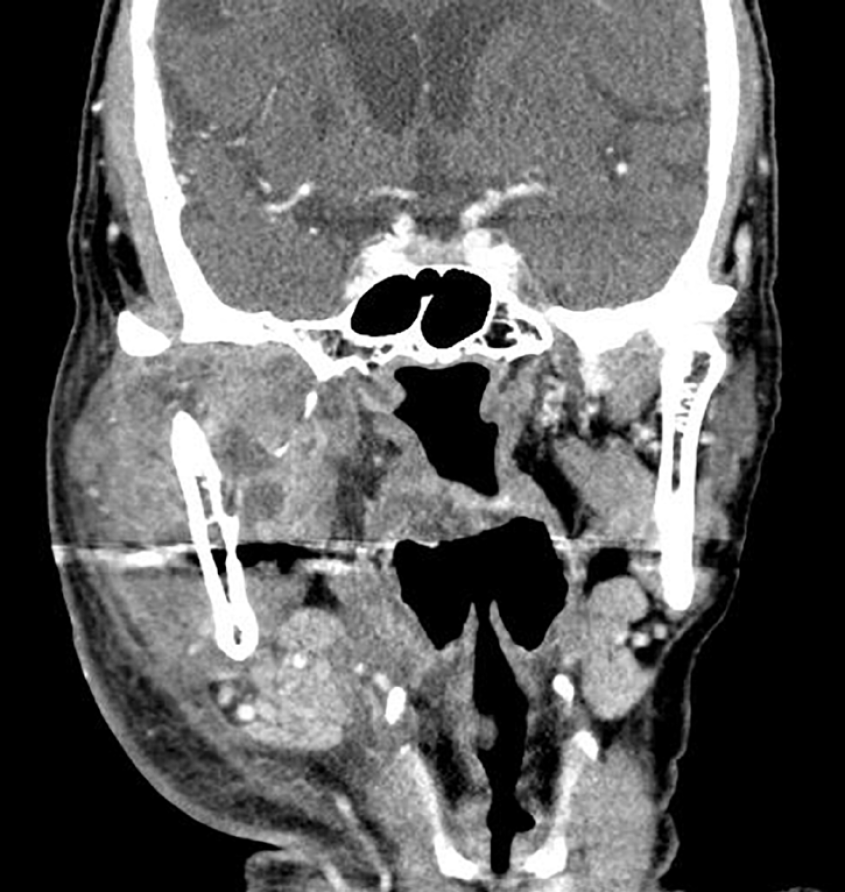

Case 1: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse thickening of the platysma muscle and subcutaneous fat stranding, as well as significant swelling in the right mastication space and parotid space, indicative of CNF (Figure 1).

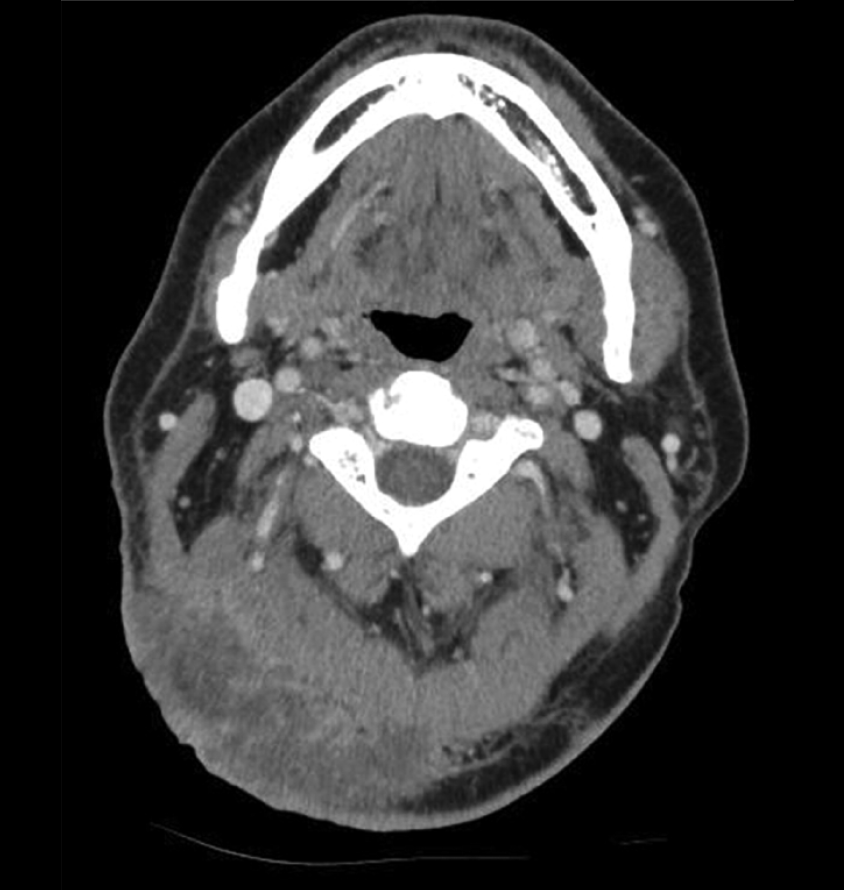

Case 2: Contrast-enhanced CT scan showed heterogeneous enhancement in the right occipital area and adjacent posterior neck region. In addition, it revealed diffuse thickening of the surrounding subcutaneous tissue and fat stranding; these findings are consistent with the presence of CNF (Figure 2).

Based on these examinations, we considered a diagnosis of CNF in the anterior neck area.

Based on these examinations, we considered a diagnosis of CNF in the posterior neck area.

Empirical broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic treatment was administered, and serial debridement was performed over a 2-wk period. Following adequate wound preparation, a flap surgery was planned for defect coverage. The final size of the defect post-debridement was 5.5 cm × 12 cm. We designed an 8 cm × 19 cm KF, based on perforators from the superior thyroid artery (Figure 3). The defect was effectively managed using the modified Type II KF, which involved division of the deep fascia along the entire circumference line of the flap. The flap survived completely, without any complications.

Empirical broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotic treatment was administered, and serial debridement performed over a 2-wk period. Following adequate wound preparation, flap surgery was planned to address the defect. The final size of the defect post-debridement was 6 cm × 11 cm, and a deep dead space was identified inside the defect. We designed a 9 cm × 18 cm-sized KF, based on perforators from the transverse cervical artery (Figure 4). The defect was effectively covered with the modified Type II KF, and the flap showed complete survival without any complications.

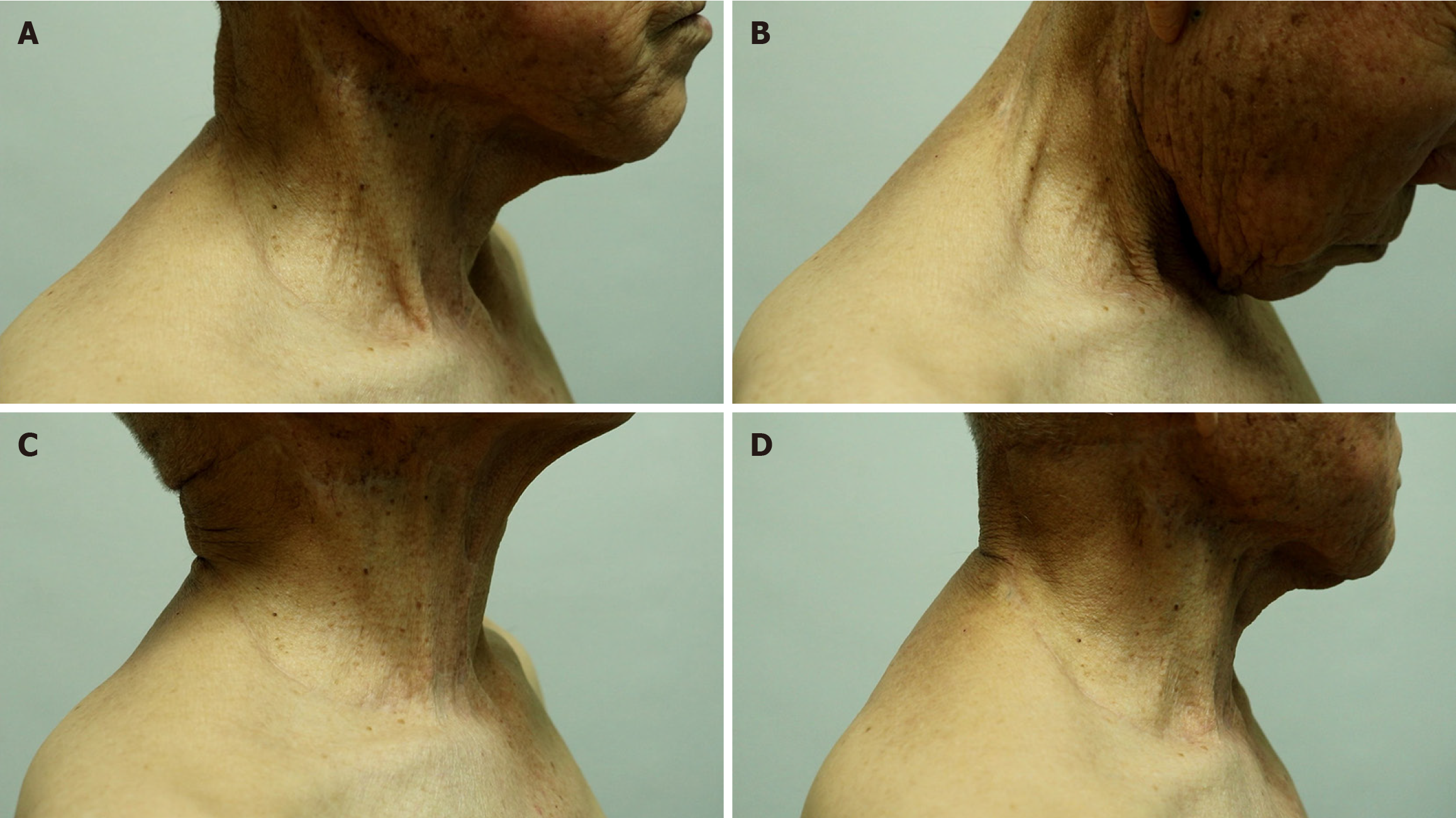

At the 7-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated a favorable functional outcome, showing no limitation in neck movement. Moreover, the patient expressed satisfaction with the final aesthetic result (Figure 5).

At the 6-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated a favorable functional outcome, with no limitations in neck movement. In addition, the patient expressed satisfaction with the overall outcome.

NF predominantly occurs in the extremities, perineum, or trunk, with occurrence in the head and neck region accounting for approximately 10% of all cases[4,6,7]. CNF in the head and neck is often caused by odontogenic abscesses resulting from dental caries or chronic periodontitis[1-4,7]. Additionally, CNF may develop as a secondary infection following trauma or upper respiratory infections[1-4,7]. In the cases presented in this study, one CNF case had an odontogenic cause, whereas the other was secondary to a skin infection.

Several risk factors have been associated with NF, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, myxedema, alcoholism, arteriosclerosis, advanced age, chronic renal failure, malnutrition, and metastatic cancer[1-4,6,7]. Notably, both cases in this report showed some of these risk factors, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic renal failure.

CNF management depends on the early initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and aggressive serial surgical debridement[4,6,7]. These strategies can decelerate the rate of tissue destruction and enhance the overall survival rate. However, serial debridement often results in defects that require reconstructive procedures, including skin grafts and flap coverage[4,5,7].

For superficial defects of any size that do not expose underlying structures, skin grafting is a straightforward and effective reconstructive option[8,9]. Nevertheless, the procedure has some limitations, such as potential skin color and texture mismatches, vulnerability to shearing and friction forces, contour deformity, and potential donor site morbidity[8,9]. In cases of deep defects involving exposed underlying structures, flap coverage is imperative for providing protective, durable tissue layers[8,9].

As previously mentioned, local flaps are suitable for small- to moderate-sized defects, as in our cases. Some studies have demonstrated the application of various local flaps, including the trapezius, pectoralis major muscle, deltopectoral, bilobed fasciocutaneous, and perforator-based fasciocutaneous flaps[8,10].

The KF has emerged as a widely utilized reconstructive modality for various defects, serving as both a primary and alternative option, regardless of the defect’s location[8,9,11,12]. This preference can be attributed to its definite advantages, including a simple and easily adjustable design to match specific defects, ease of reproducibility, and minimal learning curve for surgeons[8,9,11,12].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of KF reconstruction in the neck region[8,13-15]. Notably, our senior author has previously demonstrated successful application of KF for defect coverage in the posterior neck and lower occipital scalp[8].

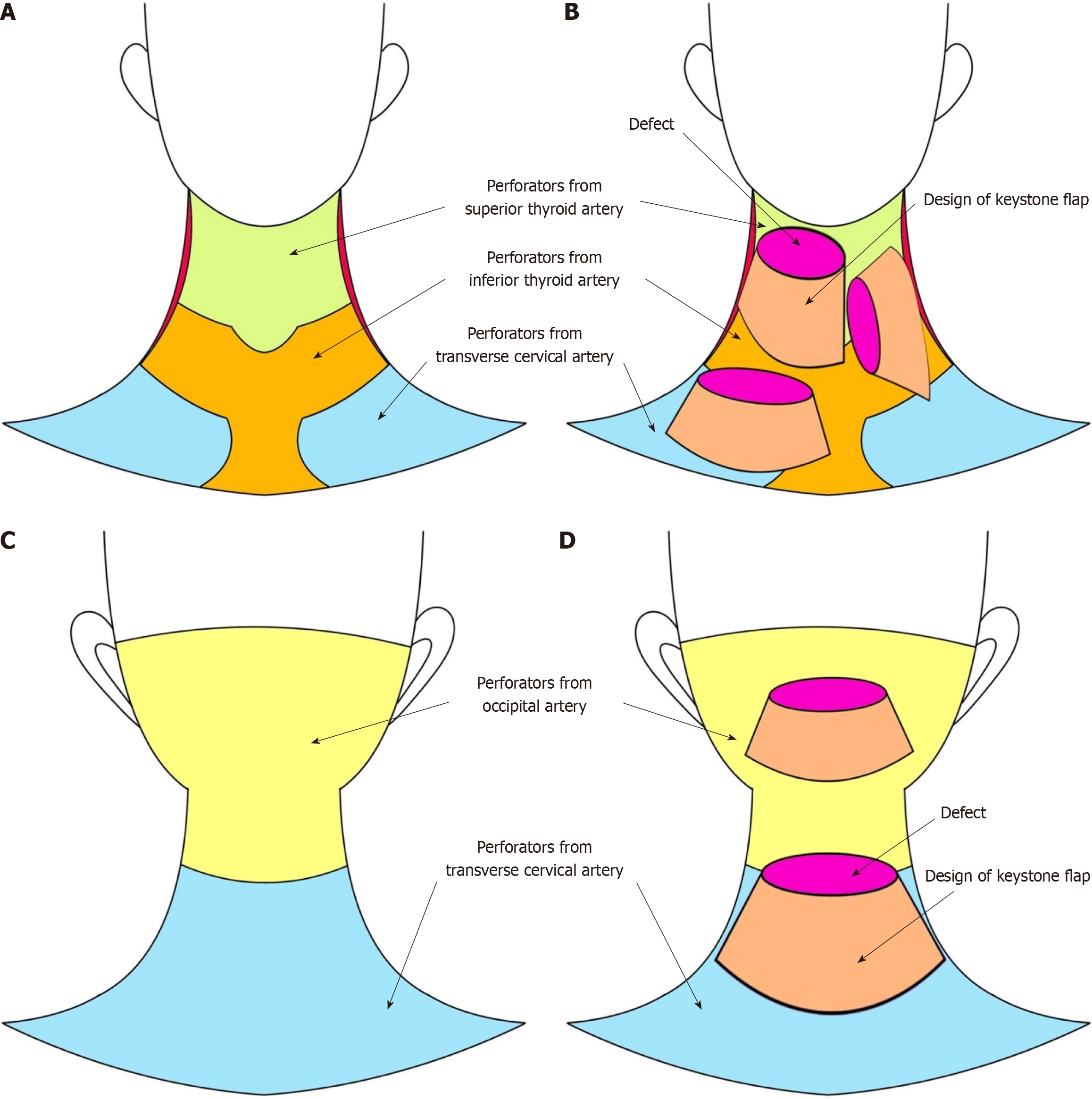

The neck area is rich in perforators, providing an excellent resource for KF advancement flaps[8]. The anterior neck has perforators arising from the superior and inferior thyroid arteries, while the posterior neck has perforators originating from the occipital and transverse cervical arteries. Owing to its multi-perforator-based nature, the KF can take full advantage of these abundant perforators in the neck region, making it a safe and reliable choice for reconstructive purposes.

Figure 6 illustrates the regions of perforators in the neck area and representative design of the KF for neck defects, including the cases presented in this study. For anterior neck defects, KF based on perforators from the superior thyroid, inferior thyroid, and transverse cervical arteries can be employed, whereas for posterior neck defects, KF based on perforators from the occipital and transverse cervical arteries is utilized.

In our cases, we utilized the modified Type II KF, which involves a complete division of the whole circumferential deep fascia along the flap boundary[9,16]. This modified approach offers enhanced flap movement compared to the original Type II KF, where deep fascia division is limited along the outer curvilinear line of the flap[9,16]. By dividing the investing layer of deep cervical fascia along the entire circumference of the flap, we achieved sufficient flap movement to effectively cover the defects[9,16].

Previous studies have demonstrated the tension-reducing effect of KF reconstruction, primarily attributed to deep fascia division[11,12]. We believe that this tension-reducing effect facilitated wound closure with minimal tension, which is crucial for neck defect coverage. Therefore, no postoperative wound complications or limitations in neck movement were observed in the cases reported here.

This study presents successful cases of CNF defect coverage using the modified KF technique and provides illustrative figures (Figure 6) to enhance reader comprehension. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first case report of CNF defect reconstruction using the modified KF in Korea. We suggest that the modified KF technique may serve as an effective reconstructive option for neck defects owing to its reliable and favorable outcomes in selected cases with small- to moderate-sized defects.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boffano P, Italy; Hrgovic Z, Germany S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

| 1. | Yang YS, Lee HU, Kim JS, Lee JK, Hong KH. A clinical study of the cervical necrotizing fasciitis. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2005;48:1020-1026. |

| 2. | Kim CH, Choung YH, Oh JH, Lee JW. Management of cervical necrotizing fasciitis. Korean J Otorhinolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2005;48:771-777. |

| 3. | Hua J, Friedlander P. Cervical Necrotizing Fasciitis, Diagnosis and Treatment of a Rare Life-Threatening Infection. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023;102:NP109-NP113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gupta V, Sidam S, Behera G, Kumar A, Mishra UP. Cervical Necrotizing Fasciitis: An Institutional Experience. Cureus. 2022;14:e32382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Choi JA, Kwak JH, Yoon CM. Life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis of the posterior neck. J Trauma Inj. 2020;33:260-263. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, Sotiropoulos D, Kanavidis P, Machairas A. Current concepts in the management of necrotizing fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gunaratne DA, Tseros EA, Hasan Z, Kudpaje AS, Suruliraj A, Smith MC, Riffat F, Palme CE. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis: Systematic review and analysis of 1235 reported cases from the literature. Head Neck. 2018;40:2094-2102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kong YT, Kim J, Shin HW, Kim KN. Keystone Flaps for Coverage of Defects in the Posterior Neck and Lower Occipital Scalp: A Retrospective Clinical Study. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1813-1816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoo BW, Oh KS, Kim J, Shin HW, Kim KN. Modified Keystone Perforator Island Flap Techniques for Small- to Moderate-Sized Scalp and Forehead Defect Coverage: A Retrospective Observational Study. J Pers Med. 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JH, Foo FJ, Wong AW. Posterior cervical necrotising fasciitis: a multidisciplinary endeavour in surgery. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023:rjad127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoon CS, Kim HB, Kim YK, Kim H, Kim KN. Keystone-design perforator island flaps for the management of complicated epidermoid cysts on the back. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yoon CS, Kong YT, Lim SY, Kim J, Shin HW, Kim KN. A comparative study for tension-reducing effect of Type I and Type II keystone perforator island flap in the human back. Sci Rep. 2021;11:16699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Behan FC, Rozen WM, Wilson J, Kapila S, Sizeland A, Findlay MW. The cervico-submental keystone island flap for locoregional head and neck reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sun Y. Keystone Flap for Large Posterior Neck Defect. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:321-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pelissier P, Gardet H, Pinsolle V, Santoul M, Behan FC. The keystone design perforator island flap. Part II: clinical applications. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:888-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kim KH, Yoo BW, Lim SY, Oh KS, Kim J, Shin HW, Kim KN. Modified Keystone Perforator Island Flap for Tension-Reducing Coverage of Axillary Defects Secondary to Radical Excision of Chronic Inflammatory Skin Lesions: A Retrospective Case Series. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:5600450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |