Published online Feb 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i6.1174

Peer-review started: November 25, 2023

First decision: December 27, 2023

Revised: January 28, 2024

Accepted: February 2, 2024

Article in press: February 2, 2024

Published online: February 26, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 21 Hours

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) are two common clinical autoimmune liver diseases, and some patients have both diseases; this feature is called AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. Autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD) is the most frequently overlapping extrahepatic autoimmune disease. Immunoglobulin (IgG) 4-related disease is an autoimmune disease recognized in recent years, characterized by elevated serum IgG4 levels and infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells in tissues.

A 68-year-old female patient was admitted with a history of right upper quadrant pain, anorexia, and jaundice on physical examination. Laboratory examination revealed elevated liver enzymes, multiple positive autoantibodies associated with liver and thyroid disease, and imaging and biopsy suggestive of pancreatitis, he

This case highlights the importance of screening patients with autoimmune diseases for related conditions.

Core Tip: Autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome is relatively rare in clinical practice. In this report, we describe the case of a patient presenting with autoimmune hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, thyroid disease, and autoimmune pancreatitis overlap syndrome. The report underscores the significance of vigilance and routine screening for related autoimmune diseases to prevent missed diagnoses and treatment opportunities, which can significantly impact the disease course and the patient’s quality of life. Additionally, it highlights the importance of tailoring treatment to individual patients to optimize effectiveness and enhance patient adherence.

- Citation: Qin YJ, Gao T, Zhou XN, Cheng ML, Li H. Autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome complicated by various autoimmune diseases: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(6): 1174-1181

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i6/1174.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i6.1174

Autoimmune liver diseases include autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), and primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Rarely, patients present with clinical features of multiple autoimmune liver diseases, known as overlap syndromes (OS)[1,2]. Among the overlap syndromes, AIH-PBC OS is the most common[3,4]. IgG4-related disease is a chronic, progressive inflammatory disease resulting in fibrosis affecting the lymph nodes, salivary glands, pancreas, bile ducts, and central nervous system[5-7]. Here, we introduce a complex case of AIH-PBC OS combined with autoimmune thyroid disease (AITD) and IgG4-associated autoimmune pancreatitis (IgG4 AIP).

A 68-year-old female patient was admitted to the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University in Guiyang, China, March 21, 2021, with complaints of “right upper quadrant pain for the past year” and “nausea when consuming greasy food for the past week”.

The patient’s symptoms began a year before her presentation, characterized by right upper quadrant pain. In the week leading up to the visit, she also experienced fatigue, a decreased appetite, and accompanying nausea.

The patient has no history of alcohol consumption. She had well-controlled hypertension for the past 3 years, managed with irbesartan. In 2020, she reported experiencing upper right abdominal pain and mild scleral yellowing, although there were no systemic jaundice or itching symptoms.

The patient's daughter has been diagnosed with PBC.

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 36.3 ℃; blood pressure, 128/78 mmHg; heart rate, 72 beats per min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths per min. Mild jaundice and scleral icterus were noted, and there was tenderness to percussion in the right upper abdominal quadrant.

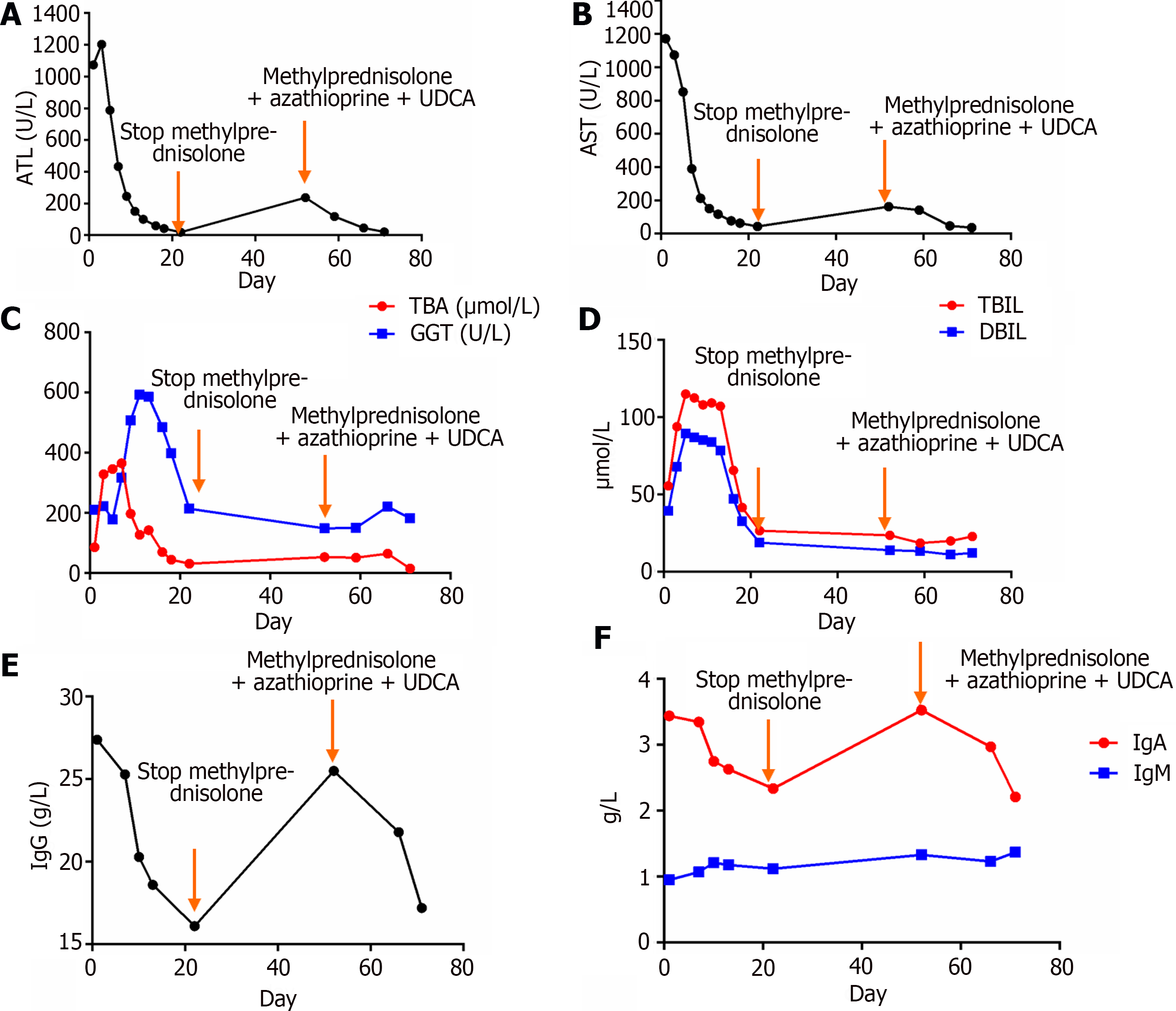

Laboratory examination revealed an alanine aminotransferase level of 1073.5 U/L (Figure 1A), an aspartate aminotransferase level of 1172.10 U/L (Figure 1B), an alkaline phosphatase level of 165.00 U/L, a gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase level of 210.42 U/L (Figure 1C), a total bilirubin level of 55.70 μmol/L with a direct bilirubin level of 39.6 μmol/L (Figure 1D) and an indirect bilirubin level of 17.65 μmol/L, a total bile acid level of 86.0 μmol/L, an albumin level of 37.00 g/L, and an albumin to globulin ratio of 0.940.

Liver disease-related autoantibodies were investigated. The patient tested positive for antinuclear antibodies (titers of 1:1000) using indirect immunofluorescence (FC 1510-1010-1, EUROIMMUN reagent, Germany), positive for anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA), and strongly positive for anti-mitochondrial M2 antibodies using indirect immunofluorescence. IgG levels were 27.4 g/L (Figure 1E), IgA levels were 3.44 g/L, IgM levels were 0.95 g/L (Figure 1F), and IgG4 Levels were 1620.9 mg/L. Thyroid function tests were normal, with an anti-thyroglobulin antibody level of 222 U/mL and an antithyroid peroxidase autoantibody level of 45.2 U/mL. The patient tested negative for hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus, and ceruloplasmin was normal. Whole-exome sequencing was negative.

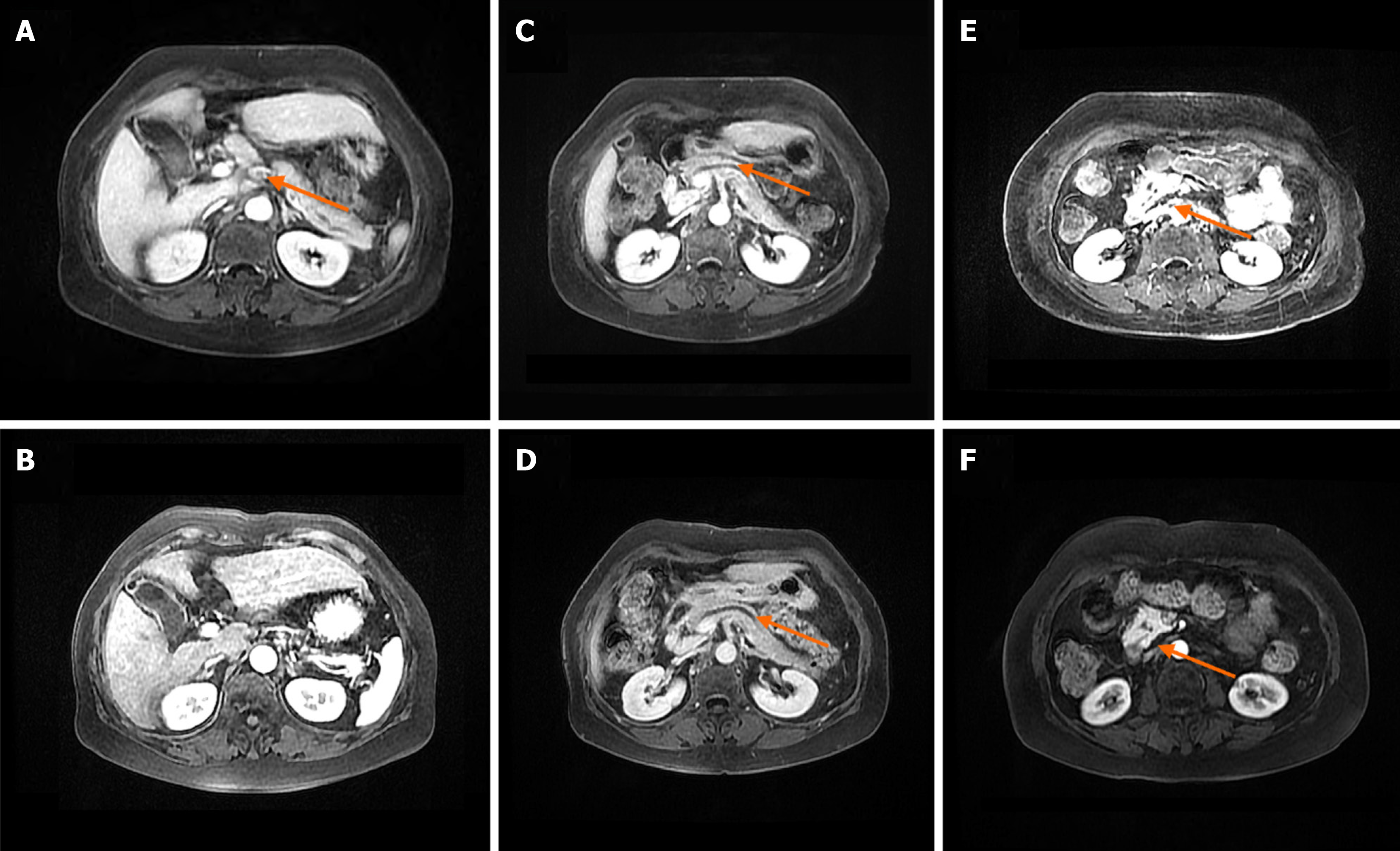

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was sought and demonstrated multiple enlarged lymph nodes surrounding the hepatic hilum and pancreatic head, slightly dilated pancreatic ducts, and nodules in the pancreatic duct and pancreatic head (Figure 2). Thyroid ultrasonography revealed diffuse thyroid enlargement with non-uniform echogenicity. Enhanced computerized tomography imaging of the upper abdomen showed multiple enlarged hilar and pancreatic head lymph nodes, and dilated pancreatic ducts. Bone densitometry demonstrated severe osteoporosis.

The patient underwent liver and pancreatic needle biopsies. An abundance of lymphocytes and plasma cells were observed in a lymph node of the porta hepatis (Figure 3A). HE staining of the liver revealed scattered liver necrosis and a large number of inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 3B). Masson staining of the liver tissue revealed fibrosis in the portal area and the formation of fibrous septa (Figure 3C). The infiltration of inflammatory cells in the portal area of the liver tissue was negative for IgG4 staining (Figure 3D) but positive for IgG staining (Figure 3E). HE staining of the pancreatic tissue revealed a small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration that could be seen in the pancreatic glands (Figure 3F). IHC staining of the pancreatic tissue was negative for IgG4 (Figure 3G) and was considered to be the result of insufficient sampling. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a dilated main pancreatic duct and multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the hepatic hilum, pancreatic head, and pancreatic lymph nodes (Figure 4A, C and D); Figure 4B shows the uncinate process of the pancreas.

Based on the physical examination, laboratory features, and imaging findings, a final diagnosis of AIH-PBC OS, AIP, and AITD was made.

The patient, with a weight of 61 kg, initially received treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid at a dose of 15 mg/kg/d and orally administered methylprednisolone at 60 mg/d, gradually reduced to 20 mg/d for maintenance. Symptomatic management of the patient’s osteoporosis involved the use of chewable vitamin D calcium tablets. Subsequently, the patient’s liver function showed significant improvement, and serum levels of IgG4, IgG, IgA, and IgM decreased. This improvement led to the patient's discharge from the hospital (Figure 1). After discharge, the patient discontinued methylprednisolone due to experiencing tremors and increased blood pressure. Consequently, the patient’s liver function deteriorated. Prior to initiating azathioprine, genetic testing was performed for the patient’s TPMT and NUDT15 genes, both of which showed normal results. As a result, the patient's medication regimen was adjusted to include ursodeoxycholic acid at 15 mg/kg/d, methylprednisolone at 8 mg/d, and azathioprine at 50 mg/d, resulting in another improvement in liver function.

The patient responded well to the standard clinical treatment, with her liver function and overall physical condition returning to a satisfactory level. All indicators for the patient are now within the normal range. She continues to be under continuous follow-up.

Both AIH and PBC are immune-mediated liver diseases with different clinical and biochemical manifestations, with 2%-19% of AIH patients being diagnosed with overlapping PBC and 7%-14% of AIH patients developing overlapping PSC. AIH mainly causes hepatocellular damage, while PBC mainly targets the bile ducts[8,9]. The diagnosis of AIH-PBC OS is made using the Paris criteria: interface hepatitis on liver histopathology in conjunction with laboratory and biopsy results meeting the diagnostic criteria of PBC. The diagnostic criteria for AIH are as follows: (1) ALT ≥ 5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN); (2) IgG ≥ 2 ULN or anti-smooth muscle antibody ≥ 1:80; and (3) at least 2 of periportal or interlobular lymphocytic infiltration and borderline hepatitis on liver biopsy. The diagnostic criteria for PBC are as follows: (1) ALT ≥ 2 ULN or GGT ≥ 5 ULN; (2) AMA ≥ 1:40; and (3) at least two bile duct lesions in liver biopsy. When both these sets of criteria are met, AIH-PBC OS can be diagnosed[10,11]. The biochemical indicators, immunological indicators, and liver histopathological characteristics of this patient were consistent with AIH-PBC OS.

The recommended treatment regimen for patients with AIH-PBC is long-term or lifelong administration of ursodeoxycholic acid combined with glucocorticoids[12]. In this case, the biochemical indexes improved rapidly after treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid and glucocorticoids, and the indexes rebounded after discontinuing the drug due to side effects.

IgG4-related diseases are immune-mediated diseases that have been gradually recognized and valued in recent years. They can affect almost all organs and tissues in the body, such as the pancreas, biliary tract, breast, kidney, and so on. The clinical manifestations vary depending on the involved organs. IgG4 hepatobiliary disease includes IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis and IgG4-related liver disease[13]. The diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related diseases were published by the Japanese scientific research group in 2011: (1) Diffuse or characteristic nodules, masses, and swellings in single or multiple organs; (2) serum IgG4 level ≥1.35 g/L; and (3) histopathology: (a) obvious lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration and fibrotic or sclerotic changes; (b) IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration with an IgG4/IgG ratio > 0.4 and IgG4-positive plasma cells > 10/high power field. The gold standard for the diagnosis of IgG4-related disease relies on histopathology and immunohistochemical staining of IgG4-positive plasma cells. In this case, IgG4 was significantly elevated at the initial diagnosis, but no typical IgG4 sclerosing cholangitis manifestations, such as bile duct stenosis and deformation, were found on imaging. IgG4-related autoimmune hepatitis was excluded on the basis of negative IgG4 staining on liver biopsy.

IgG4-AIP has the highest incidence among IgG4-related disease, and the early misdiagnosis rate is high[14]. This patient's magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed an enlarged pancreatic head and mild dilatation of the pancreatic duct. The patient's serum IgG4 Levels were 1620.9 mg/L, over 1350 mg/L. Imaging examination showed focal enlargement of the pancreatic head, and the pancreatic duct was dilated, although the degree of dilatation was less than 0.5 cm. Negative IgG4 immunohistochemistry in the pancreatic tissue was considered to be the result of insufficient sampling; therefore, insufficient sampling is a limitation of our study. Although autoimmune thyroiditis was diagnosed based on elevated autoantibodies and ultrasonographic abnormalities, no thyroid biopsy was performed, and IgG4-related thyroid disease could not be confirmed or excluded.

Autoimmune liver disease is sometimes associated with AITD and connective tissue disorders such as systemic sclerosis or Sjögren's syndrome[15]. The most common extrahepatic diseases associated with AIH type 1 are thyroiditis, ulcerative colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis. There are case reports of PBC-AIH OS with diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis, and antiphospholipid syndrome. Pamfil et al[16] reported that 61.2% of patients with PBC have extrahepatic autoimmune disease, and up to 46.6% have one or more connective tissue diseases. AITD is observed in 23% of PBC patients and 18.3% of PBC-AIH OS patients. As a result of active screening, our awareness of extrahepatic diseases such as AITD has increased. Being aware of related autoimmune diseases enables clinicians to avoid missing a diagnosis of AIH-PBC combined with other autoimmune diseases. Autoimmune diseases are multisystemic, and missed diagnoses can affect treatment and disease monitoring. Therefore, for patients with autoimmune liver diseases, clinicians should be vigilant for the coexistence of related autoimmune diseases.

Studies have shown that genetic factors are closely related to the occurrence and development of autoimmune liver diseases (AILD). Each subtype of AILD demonstrates familial aggregation[17]. WES detection technology is a powerful tool for finding genetic mutations in genetic diseases. It is mainly used for the related research of complex diseases and Mendelian genetic diseases caused by mutations in coding regions, especially for the search for pathogenic mutation genes in rare familial genetic diseases. It can play a key role in clinical decision-making and can obtain single nucleotide polymorphism maps of 90% of the genome coding regions, including rare variants and new variants[18]. In this case, the WES test was negative, and genetic factors were not considered for the time being.

This patient presented a complex case with multiple diseases. Since autoimmune hepatitis is characterized by liver damage caused by autoimmune dysfunction, when it is combined with other immune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome, etc., patients will have corresponding extrahepatic manifestations, such as joint pain, dry eyes, dry mouth, itchy skin, and other symptoms. Fortunately, the patient reported here did not have the above-mentioned extrahepatic manifestations, but the diagnosis of such diseases still needs to be carefully screened. Similarly, missing the diagnosis of AIH should be avoided in patients with extrahepatic manifestations, and in this regard, a liver biopsy should be performed if necessary.

Patient rescue therapy and follow-up are crucial. It is necessary to explain to the patient that after discharge, they should focus on rest, avoid fatigue, consume a light and easily digestible diet, enhance their nutritional intake, and strictly avoid medications that could harm the liver. After discharge, the patient must continue following the doctor's instructions, which include taking methylprednisolone (2 tablets of 8 mg each) and one tablet of azathioprine (50 mg) daily. The patient should also schedule a follow-up appointment at the liver disease clinic 1 wk after discharge. For patients with hypertension, irbesartan should be continued to control blood pressure and monitor any fluctuations. In cases of inadequate blood pressure control, seeking medical attention at a hypertensive clinic is advised. Throughout the medication process, patients are required to visit the liver disease clinic every 3 months for follow-up to monitor their physical condition. Currently, the patient remains under follow-up, and the treatment effect remains favorable.

This case report underscores that autoimmune diseases are multisystemic, and it highlights the intricate and severe clinical course of this disease. As demonstrated, patients with autoimmune diseases have an elevated risk of developing other immune-mediated diseases. Therefore, it is essential to conduct tests for additional autoantibodies and perform necessary histopathological examinations to screen for additional diagnoses. This patient responded positively following the timely initiation of treatment, and the biochemical response remained favorable after transitioning to a low-dose triple-drug regimen due to side effects. This emphasizes the importance of customizing treatment plans based on factors such as the patient's age, underlying disease, and drug tolerance.

We thank the patient for her contribution to this case report.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Montasser IF, Egypt S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Diagnosis and management of overlap syndromes. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19:81-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chazouillères O. Overlap Syndromes. Dig Dis. 2015;33 Suppl 2:181-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Freedman BL, Danford CJ, Patwardhan V, Bonder A. Treatment of Overlap Syndromes in Autoimmune Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jiang Y, Xu BH, Rodgers B, Pyrsopoulos N. Characteristics and Inpatient Outcomes of Primary Biliary Cholangitis and Autoimmune Hepatitis Overlap Syndrome. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2021;9:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chen LYC, Mattman A, Seidman MA, Carruthers MN. IgG4-related disease: what a hematologist needs to know. Haematologica. 2019;104:444-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Minaga K, Watanabe T, Chung H, Kudo M. Autoimmune hepatitis and IgG4-related disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:2308-2314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Wallace ZS, Perugino C, Matza M, Deshpande V, Sharma A, Stone JH. Immunoglobulin G4-related Disease. Clin Chest Med. 2019;40:583-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Gerven NM, de Boer YS, Mulder CJ, van Nieuwkerk CM, Bouma G. Auto immune hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:4651-4661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 9. | Tanaka A. Current understanding of primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27:1-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bairy I, Berwal A, Seshadri S. Autoimmune Hepatitis - Primary Biliary Cirrhosis Overlap Syndrome. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:OD07-OD09. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gilchrist AA. Potency in psychotherapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1976;10:191-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Castro Limo JD, Romero-Gutiérrez M, Ruiz Martín J. Effective treatment of autoimmune hepatitis-primary biliary cholangitis overlap syndrome with obeticholic acid. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iaccarino L, Talarico R, Scirè CA, Amoura Z, Burmester G, Doria A, Faiz K, Frank C, Hachulla E, Hie M, Launay D, Montecucco C, Monti S, Mouthon L, Tincani A, Toniati P, Van Hagen PM, Van Vollenhoven RF, Bombardieri S, Mueller-Ladner U, Schneider M, Smith V, Cutolo M, Mosca M, Alexander T. IgG4-related diseases: state of the art on clinical practice guidelines. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Okamoto A, Watanabe T, Kamata K, Minaga K, Kudo M. Recent Updates on the Relationship between Cancer and Autoimmune Pancreatitis. Intern Med. 2019;58:1533-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khoury T, Kadah A, Mari A, Sbeit W, Drori A, Mahamid M. Thyroid Dysfunction is Prevalent in Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Case Control Study. Isr Med Assoc J. 2020;22:100-103. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Pamfil C, Candrea E, Berki E, Popov HI, Radu PI, Rednic S. Primary biliary cirrhosis--autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome associated with dermatomyositis, autoimmune thyroiditis and antiphospholipid syndrome. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2015;24:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zachou K, Arvaniti P, Lyberopoulou A, Dalekos GN. Impact of genetic and environmental factors on autoimmune hepatitis. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4:100125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rakela J, Rule J, Ganger D, Lau J, Cunningham J, Dehankar M, Baheti S, Lee WM; Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Whole Exome Sequencing Among 26 Patients With Indeterminate Acute Liver Failure: A Pilot Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:e00087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |