Published online Feb 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i5.1025

Peer-review started: December 10, 2023

First decision: December 18, 2023

Revised: December 28, 2023

Accepted: January 22, 2024

Article in press: January 22, 2024

Published online: February 16, 2024

Processing time: 51 Days and 17.2 Hours

A man experienced multiple episodes of macroscopic hematuria following nocturnal exercise. Urinary stones and tumors were considered the two most likely causes. The patient had two hobbies: Consuming health care products in large quantities and engaging in late-night running.

Health care products contain a large amount of calcium phosphate, and we hypothesize that this could induce the formation of small phosphate stones. After exercise, the urinary system is abraded, resulting in bleeding. The patient was advised to stop using the health care products. Consequently, the aforementioned symptoms disappeared immediately. However, the patient resumed the above two habits one year later; correspondingly, the macroscopic hematuria reap

This finding further confirmed the above inference and allowed for a new avenue to determine the cause of the patient’s hematuria.

Core Tip: If patients take a lot of healthcare products containing calcium phosphate, amorphous phosphate crystals may appear in urine. Once they do exercise, they may scratch the urethra and cause hematuria.

- Citation: Bai MJ, Yang ST, Liu XK. Hematuria after nocturnal exercise of a man: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(5): 1025-1028

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i5/1025.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i5.1025

Multiple studies have shown that clinical hematuria is common after exercise[1], with 95-100% of the patients with clinical hematuria having it after exercise[2]. The degree of hematuria is related to the intensity of the exercise; for instance, contact sports can increase the risk of macroscopic hematuria. Exercise-related urological trauma is regarded as the leading cause of macroscopic hematuria, of which renal trauma accounts for 80% of cases. Here, we present the case of a patient with macroscopic hematuria who consumed a significant amount of health care products orally and favored exercise.

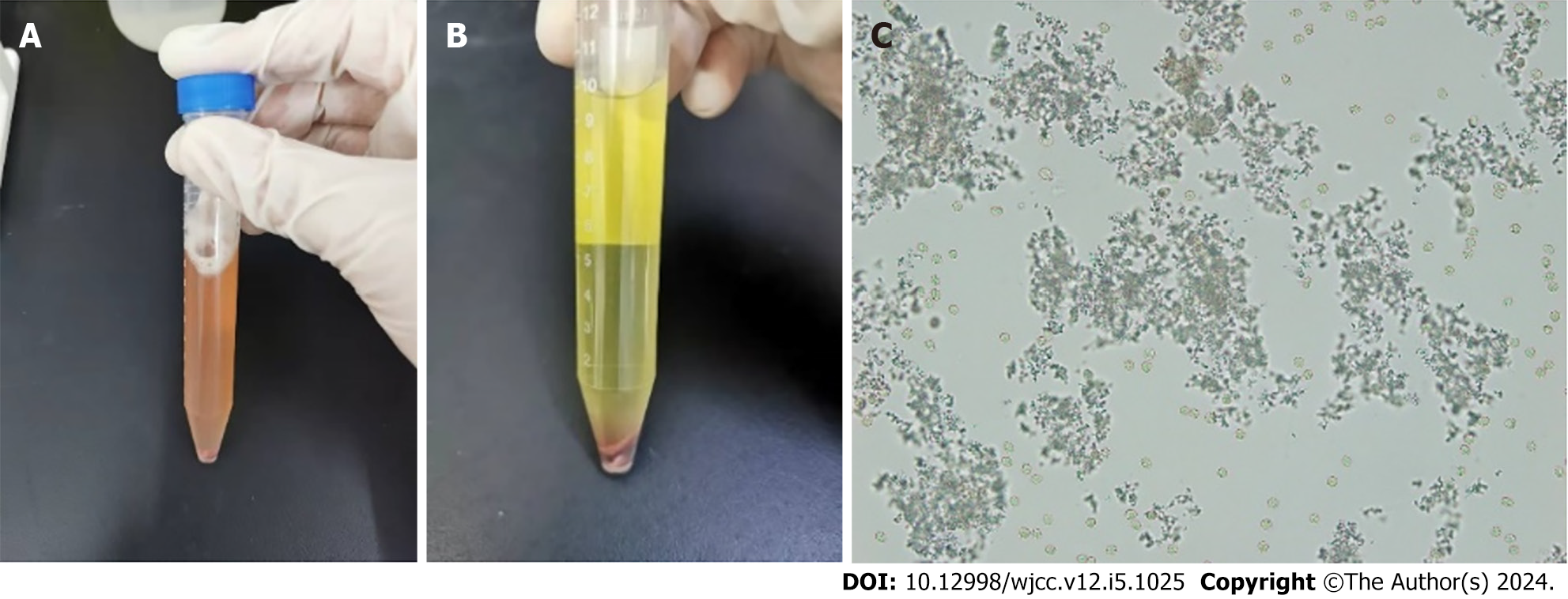

A 42-year-old man was admitted to the Emergency Department of our hospital on June 14, 2020 due to macroscopic hematuria after nocturnal exercise (Figure 1).

Upon reviewing the medical history, the patient experienced macroscopic hematuria three times after nocturnal exercise in the previous four years, and the hematuria was accompanied by lower abdominal pain. However, the actual cause of the disease had not been determined. Following a multidisciplinary team consultation, it was speculated that the nutcracker phenomenon, the very small stone traumatizing the mucosa, and urinary tract tumors were the three most likely causes of the patient’s hematuria.

No special notes.

No special notes.

No special notes.

We conducted routine urine tests, Doppler ultrasound, computed tomography urography, and endoscopic examination of the urinary system. The results indicated that only the routine urine test was abnormal, revealing urine protein (+), occult blood (++), and a red blood cell count of 21587.0 cells/μL. Additionally, a significant number of amorphous phosphate crystals were observed under the microscope (Figure 1).

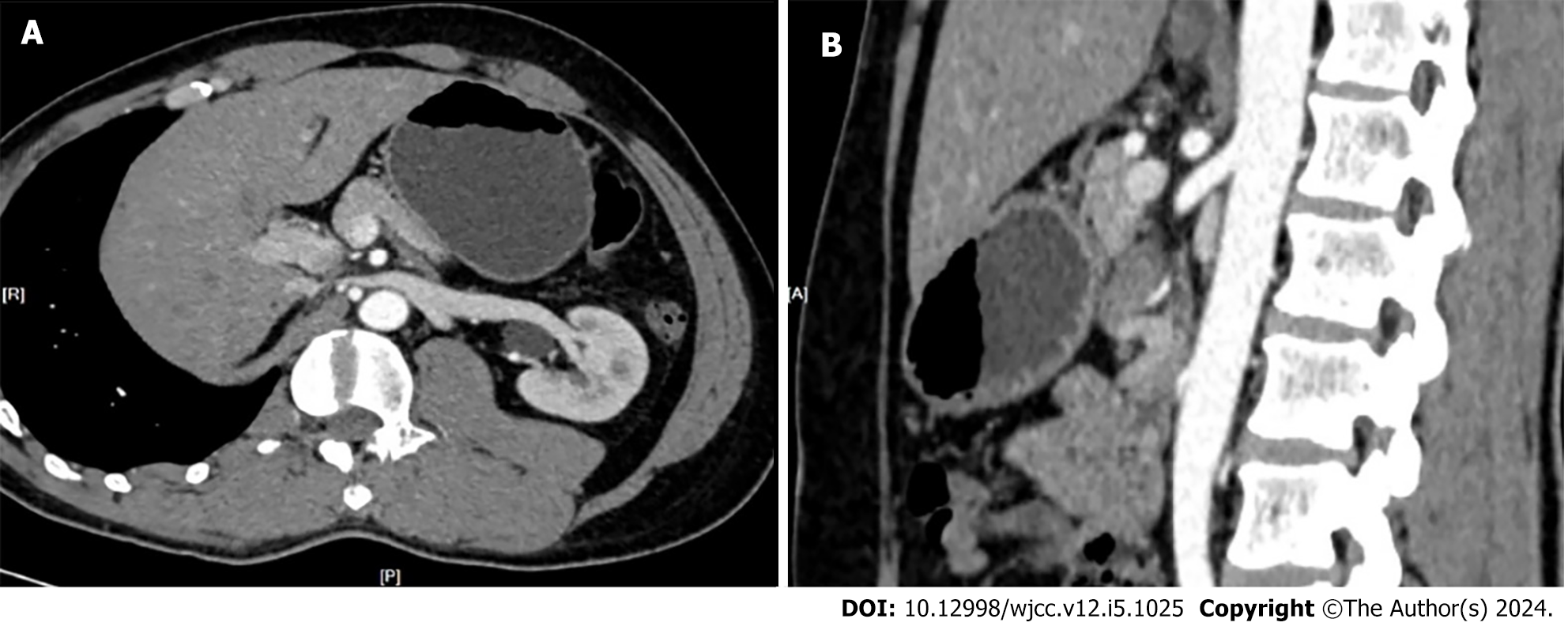

No obvious compression changes were observed in the left renal vein. The angle between the superior mesenteric artery and abdominal aorta was 41 degrees (Figure 2). At this point, hematuria caused by the nutcracker phenomenon and urologic neoplasms were essentially ruled out.

We re-inquired the patient again, with a focus on his lifestyle habits. The patient particularly enjoyed doing two things: taking large doses of health care products and exercising late at night. Upon reviewing the labels of the health care products, we identified calcium phosphate as one of the main components.

A hypothesis was formulated: the patient had orally consumed excessive amounts of health care products containing calcium phosphate, leading to the formation of tiny stones in the urine. These stones are not easily detected by imaging or endoscopy. Following nocturnal exercise, these tiny stones scratch the mucosa of the urinary system, resulting in bleeding and abdominal pain.

Based on the above assumptions, the patient was advised to stop using the health care products after discharge.

Subsequently, the patient's hematuria disappeared. However, one year later, the patient consumed the aforementioned health care products in large quantities again, and his hematuria recurred after late-night exercise. It was then confirmed that the patient’s hematuria was caused by the consumption of health care products containing calcium phosphate. The patient was again advised to stop using those health care products, at which point the patient's hematuria then disappeared.

Hematuria is a common phenomenon following exercise[1]. A previous study provided evidence of the relationship between hypercalciuria and postglomerular hematuria in children[3]. Escribano et al[4] also discovered that hypercalciuria can lead to recurrent macroscopic or microscopic hematuria. Through follow-up, it was observed that the occurrence of hematuria after exercise was clearly associated with the patient's use of the aforementioned health care products. Consequently, we deduced the pathogenesis of this patient: the abundance of amorphous phosphate leads to the formation of crystals in the urine. These crystals may scratch the urethra during exercise, ultimately resulting in hematuria.

In conclusion, if patients consume a significant quantity of health care products containing calcium phosphate, amorphous phosphate crystals may appear in the urine. During exercise, these crystals may scratch the urethra, leading to hematuria. Therefore, the present case provides a new avenue for determining the cause of hematuria in clinical practice.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shalaby MN, Egypt S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Akiboye RD, Sharma DM. Haematuria in Sport: A Review. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5:912-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mousavi M, Sanavi S, Afshar R. Effects of continuous and intermittent trainings on exercise-induced hematuria and proteinuria in untrained adult females. NDT Plus. 2011;4:217-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Reusz G, Szabó A. Hypercalciuria and postglomerular hematuria in children. The effects of thiazide on calcium excretion, urine saturation with respect to calcium-hydrogenphosphate and hematuria. Acta Paediatr Hung. 1990;30:63-71. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Escribano J, Balaguer A, Roqué i Figuls M, Feliu A, Ferre N. Dietary interventions for preventing complications in idiopathic hypercalciuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD006022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |