Published online Feb 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.865

Peer-review started: November 26, 2023

First decision: November 30, 2023

Revised: December 6, 2023

Accepted: January 8, 2024

Article in press: January 8, 2024

Published online: February 6, 2024

Processing time: 60 Days and 1.3 Hours

Meckel’s diverticulum is a common congenital malformation of the small intestine, with the three most common complications being obstruction, per

This report presents three cases of appendicitis in children combined with intestinal obstruction, which was caused by fibrous bands (ligaments) arising from the top part of Meckel's diverticulum, diverticular perforation, and diver

Preoperative diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulum and its complications is challenging because its clinical signs and complications are similar to those of appendicitis in children. Laparoscopy combined with laparotomy is useful for diagnosis and treatment.

Core Tip: Meckel's diverticulum is a congenital disorder with abnormal development of the gastrointestinal tract, which is easily confused with the clinical manifestations of acute abdominal conditions in children. We report three cases of acute appendicitis combined with Meckel's diverticulum causing obstruction, perforation, and inflammation. This disease is rare and is easily confused with appendicitis. In Meckel's diverticulum, laparoscopic surgery can diagnose and resolve the disorder. The differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children is of high educational and clinical importance.

- Citation: Sun YM, Xin W, Liu YF, Guan ZM, Du HW, Sun NN, Liu YD. Appendicitis combined with Meckel’s diverticulum obstruction, perforation, and inflammation in children: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(4): 865-871

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i4/865.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.865

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital malformation of the gastrointestinal tract, occurring in 2% of the total population, with major complications including inflammation, intestinal obstruction, and perforation[1]. Patients often become symptomatic in the first decade of life with an average age of 2.5 years[2]. According to one of the largest databases of children with symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum, only 2% are symptomatic, and of these, 60% present with obstruction and 8% with inflammation[3]. The most common presentation in childhood is gastrointestinal bleeding followed by intestinal obstruction. Symptoms associated with diverticula have been reported in approximately 50% of cases[4]. Small bowel obstruction caused by ligaments (fibrous bands) originating from Meckel's diverticulum is very rare[5]. It is easily confused with acute abdomen such as acute appendicitis in children, which is difficult to recognize on imaging. Recent studies have shown that Meckel's diverticulum is difficult to diagnose[6]. A case of Meckel's diverticulum combined with appendicitis in an adult was recently reported[7]. Recent neonatal case reports have also demonstrated that symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum is usually secondary to intestinal disorders such as intestinal obstruction, and therefore can be easily confused with an acute abdomen[8]. The diagnosis of Meckel's diverticulum-related diseases is often challenging, and imaging plays an important role in the timely recognition and differentiation of other common diseases that may have similar clinical presentations[9].

The cases reported here include a comprehensive dataset of the clinical course, diagnostic imaging, histopathologic description, and surgical information. This report will provide physicians with valuable experience in the diagnosis and treatment of acute abdomen in children.

Case 1: The patient had abdominal pain for 3 d, which was aggravated for 3 h.

Case 2: The patient had abdominal pain for 8 h.

Case 3: The patient had abdominal pain for 3 d.

Case 1: The boy who was 12 years old was admitted to hospital due to spasmodic intermittent abdominal pain of 3 d duration which was aggravated for 3 h, accompanied by nausea and vomiting of gastric contents.

Case 2: The 11-year-old boy was admitted to hospital due to paroxysmal abdominal cramps for 8 h, accompanied by nausea and vomiting of gastric contents. The child was febrile with a maximum temperature of 38.9 °C.

Case 3: The 12-year-old boy was admitted to hospital due to paroxysmal abdominal pain for 3 d accompanied by nausea and vomiting of gastric contents. The child did not have a fever.

The 3 patients had no relevant history of past illness.

The 3 patients had no relevant personal or family history.

Case 1: The child's abdomen was flat, with slightly tense abdominal muscles, marked pressure in the right lower abdomen and around the umbilicus, and rebound pain.

Case 2: The child had a flat abdomen, slightly tense abdominal muscles, and right lower abdominal pressure without significant rebound pain.

Case 3: The child's abdomen was flat, with soft abdominal muscles, marked periumbilical pressure, and mild right lower abdominal pressure without rebound pain.

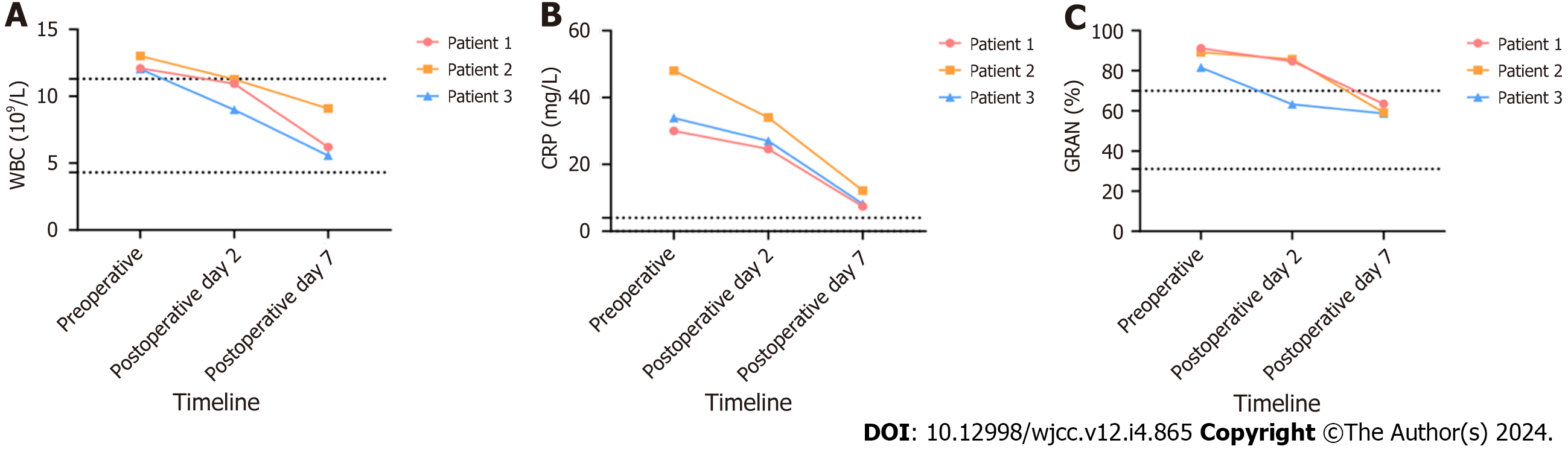

Case 1: Routine blood tests showed the following: white blood cell (WBC) count: 12.1 × 109/L, C-reactive protein (CRP): 30 mg/L, and granulocyte (GRAN): 91.2%.

Case 2: Routine blood tests showed the following: WBC: 13.02 × 109/L, CRP: 48 mg/L, and GRAN: 89.2%.

Case 3: Routine blood tests showed the following: WBC: 12.03 × 109/L, CRP: 33.9 mg/L, and GRAN: 81.5%.

Case 1: Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed suspected appendicitis; blurred and cloudy localized fat spaces in the abdominal cavity; part of the intestinal tract was pneumatized and dilated. Appendix ultrasound suggested intestinal dilatation, and appendicitis was suspected.

Case 2: Abdominal CT indicated suspected appendicitis; blurred and cloudy localized fat spaces in the abdominal cavity; part of the intestinal tract was pneumatized and dilated. Appendix ultrasound suggested possible appendicitis.

Case 3: Abdominal CT indicated that part of the small intestine was dilated and pneumatized, but there was no gas-liquid plane shadow. This suggested possible appendicitis or incomplete intestinal obstruction. Appendix ultrasound showed intestinal dilatation, right lower abdomen, interintestinal fluid (the deepest about 1.3 cm), suggesting possible app

Case 1: Meckel's diverticulum, acute appendicitis, and intestinal obstruction.

Case 2: Perforation of Meckel's diverticulum, and acute appendicitis.

Case 3: Meckel's diverticulum inflammation, and acute appendicitis.

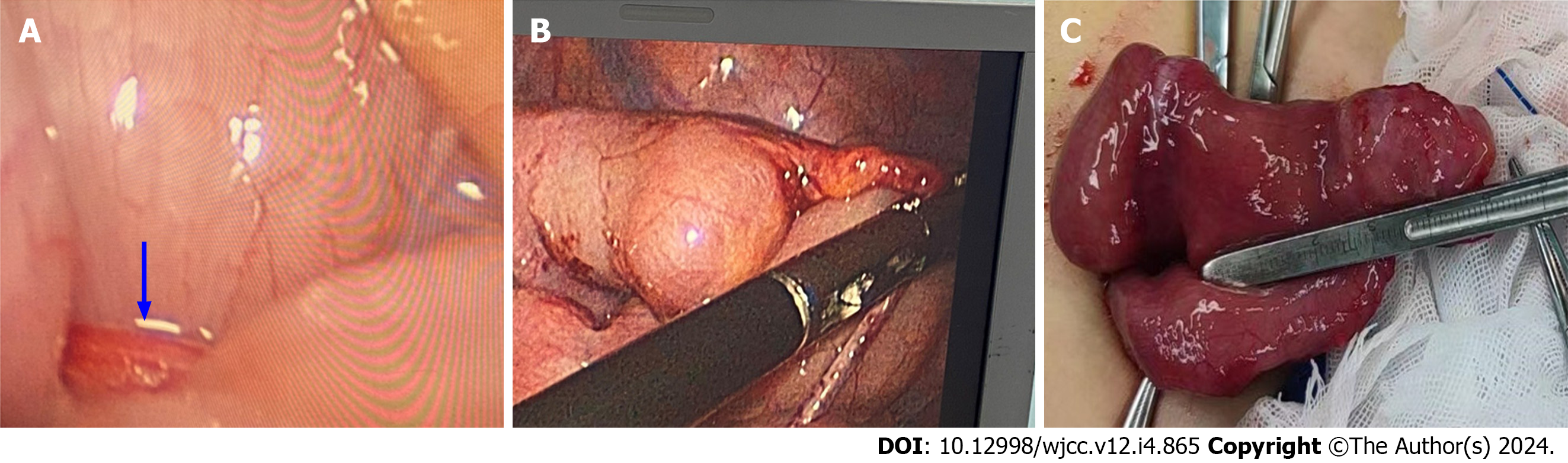

Case 1: After 24 h of cephalosporin anti-infective treatment, the child's abdominal distension worsened and after communication with his family, laparoscopic exploration was performed. Intraoperative exploration showed serious intestinal tube distension, and the field of view was seriously obstructed. A 10 mL syringe was used for intestinal decompression, 5 min later, the field of view gradually cleared and a large amount of yellow liquid was seen in the abdominal cavity. Approximately 200 mL of the fluid was aspirated and examination revealed that 100 cm of the ileocecal value was compressed, and a 4 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm diverticulum was seen. The diverticulum was located at the top of the posterior wall of the peritoneum and a mesodiverticular band (Figure 1A) was visible, which was compressing part of the small bowel canal, resulting in strangulation of several bowel segments. No ischemia or small bowel necrosis was observed. Simultaneous exploration of the appendix revealed an enlarged, mildly edematous appendiceal end without suppuration or perforation. Therefore, the appendix was resected, the mesodiverticular band was secured distally with HemoLock clips, and was then severed by fine electrosurgical dissection, thereby releasing the obstructed intestinal collaterals (Meckel's diverticulum, Figure 1B) and the proximal diverticulum apical to the mesodiverticular band was marked. The labeled Meckel's diverticulum intestinal segment (Figure 1C) was completely removed from the intestinal lumen by an umbilical laparoscopic incision, the supplying vessels were ligated, and the intestinal canal was wedged and anastomosed.

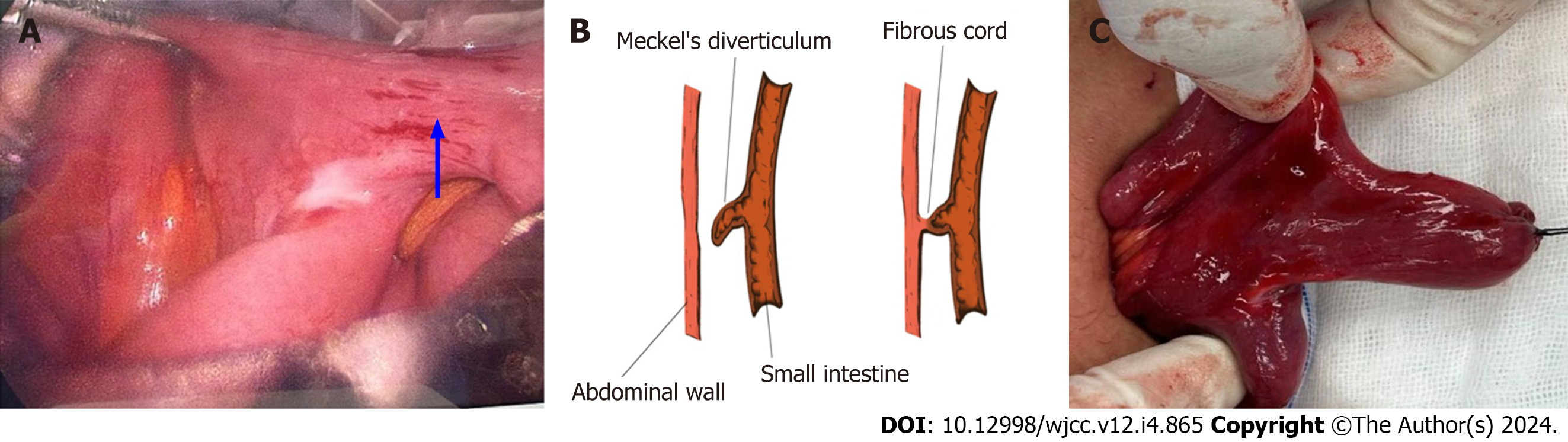

Case 2: A laparoscopic appendectomy was planned for this patient. Intraoperative exploration showed yellow pus in the pelvic cavity, approximately 20 mL was aspirated, the small intestine in the lower abdomen was adhered into a mass, and there was a large amount of pus attached to the intestinal wall, After placing the trocar, separating the large omentum and adherent intestinal wall, a huge diverticulum was seen in the opposite edge of the mesentery of the small intestinal wall 100 cm from the ileocecal region, which was approximately 3 cm × 3 cm in size, with more pus on the surface (Figure 2A), and a perforation could be seen at the root of the diverticulum, connecting with the surface of the small intestinal tract. Congestion and edema were obvious. Continued examination of the small bowel for 2 m revealed no other lesions. The appendix was also explored and found to be elongated, with a congested and edematous surface, no pus or perforation was observed. Therefore, the appendix was removed and the perforated diverticulum was marked. The umbilicus was extended downward by a 1-cm incision, and the labeled Meckel's diverticulum was completely raised from the umbilical laparoscopic incision, and the mesentery of the small intestine was cut 5 cm from the root of the diverticulum on both sides, and after cutting the intestinal tubes, the incised mesentery of the small intestine was closed with sutures. The Meckel's diverticulum was completely resected (Figure 2B), and the incision revealed a large amount of pus attached to it (Figure 2C).

Case 3: A laparoscopic appendectomy was planned for this patient. Intraoperative exploration showed that the ileocecum was located above the iliac fossa, the ileocecal intestinal tube was adhered to the iliac fossa, and the appendix was wrapped by the ileocecal intestinal tube and the greater omentum. Separation of the greater omentum and adherent intestinal wall, adherent intestinal tubes and the omentum was carried out, and the appendix was seen to be enlarged and congested, with no sepsis or perforation observed. Therefore, the appendix was removed. The ileocecal intestinal canal was explored proximally from the ileocecal region, and a diverticulum-like protrusion was seen at the opposite edge of the mesentery approximately 100 cm from the ileocecal region, with redness and swelling at the end of the diverticulum (Figure 3A), thickening, and no signs of sepsis, and the end was attached to the umbilicus (Figure 3B). Meckel's diverticulum was considered. The end was severed from the umbilicus with a fine electrosurgical knife. The incision was extended 1 cm downward from the umbilicus, and the intestinal segment of Meckel's diverticulum was completely raised into the intestinal lumen from the umbilical laparoscopic incision (Figure 3C), the supplying vessels were ligated, and the intestinal tubes were wedged and anastomosed.

Case 1: The histopathologic specimen showed chronic inflammation of intestinal mucosa, accompanied by multifocal lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoid follicle formation. The local mucosal lamina propria showed hemorrhage, and the submucosal layer was loose and edematous, which was consistent with the changes of Meckel's diverticulum; the tubular tissues were congested blood vessels.

Case 2: The histopathologic specimen showed inflammation of the intestinal mucosa with perforation, laxity, and edema of the submucosa, consistent with Meckel's diverticulum.

Case 3: The histopathologic specimen was consistent with inflammatory changes of Meckel's diverticulum. All three pediatric patients recovered uneventfully after laparoscopy, and histopathologic examination of the appendix confirmed acute simple appendicitis and histopathologic examination of the diverticulum confirmed Meckel's diverticulum. The inflammatory indices of WBC, CRP, and GARN showed a linear decreasing trend (Figure 4), and all three patients were discharged from the hospital in good health on the 7th postoperative day.

Johann Frederick Merkel first described Meckel’s diverticulum as a congenital anomaly. It is caused by incomplete occlusion of the most recent portion of the vitelline duct or umbilical mesenteric duct[10]. Meckel's diverticulum is a remnant of the embryonic vitelline duct connecting the fetal intestine to the yolk sac, which usually degenerates between the fifth and seventh weeks of gestation. Meckel's diverticulum is the most prevalent congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract with an incidence of 2%[11]. Patients are generally asymptomatic, with symptoms reported in 4%-7% of cases[12]. Almost half of children with Meckel's diverticulum present with symptoms of rectal bleeding or intussusception before the age of 2 years[1]. However, it is difficult to make a definitive diagnosis before surgery. Laparoscopy has also been reported to be a diagnostic tool in symptomatic cases of Meckel's diverticulum[10]. All three of their patients presented with total peritonitis and therefore emergency surgery was performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Intestinal obstruction caused by Meckel's diverticulum occurs via different mechanisms such as intussusception, intestinal torsion, abdominal wall hernia, Meckel's diverticulitis (Figure 3A), entrapment of intestinal collaterals below the mid-diverticular band (Figure 1A), diverticular stones, ileal collaterals trapped by bands extending between Meckel's diverticulum and the base of the mesentery, vegetative fecal stone formation, gallstone intestinal obstruction, and obstruction related to a diverticulum may behave similar to obstructions of other origins in the small bowel[4]. Intestinal obstruction caused by diverticular fibrous bands is extremely rare. The yolk sac is supplied by two arteries. If one of the two arteries of the yolk sac does not degenerate, this artery forms a fibrous band that covers the greater omentum or diverticulum (ligament). These fibrous bands usually extend from the apical level of Meckel's diverticulum to the posterior wall of the abdomen and cause intestinal obstruction[5]. At the same time, in our case, the above occurred.

Cases of perforated Meckel's diverticulum with subsequent abscess formation have been found in adults[13], but rarely in children[3]. These rare cases of perforation led us to suspect the presence of Meckel's diverticulum in our patient[5]. Our case is unique as it is one of the few case reports.

With regard to treatment, recent reports have shown that laparoscopic-assisted surgery, including even single-incision laparoscopic-assisted surgery, is feasible in children with symptomatic Meckel's diverticulum[14]. If diagnosed promptly, Meckel's diverticulum has a favorable prognosis with a mortality rate of only 1%[5]. In the present case, we performed laparoscopic surgery and as the lesion was small enough to pass through the umbilical incision, we were able to remove the lesion intact while making the incision relatively aesthetically pleasing, thus achieving a satisfactory outcome for the child's family.

There are few cases of Meckel's diverticulum combined with appendicitis in pediatric patients; therefore, there is little accurate knowledge of the age of onset in children. CT and magnetic resonance small bowel imaging or endoscopic techniques are likely to be the mainstay of Meckel’s diverticulum diagnosis in the future[15].

In children, appendicitis and Meckel's diverticulum had similar clinical manifestations, which is particularly evident when complications of Meckel's diverticulum occur. Pediatric clinicians should be aware of the distinction between these two disorders.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Glumac S, Croatia S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Choi SY, Hong SS, Park HJ, Lee HK, Shin HC, Choi GC. The many faces of Meckel's diverticulum and its complications. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2017;61:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | An J, Zabbo CP. Meckel Diverticulum. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mendoza Alvarez L, Rajderkar D, Beasley GL. An Unusual Case of a Perforated Meckel's Diverticulum. Case Rep Pediatr. 2023;2023:2289520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Kuru S, Kismet K. Meckel's diverticulum: clinical features, diagnosis and management. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110:726-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dang VC, Tran PN, Tran MC, Pham VT, Nguyen TTN. Intestinal obstruction due to ligament arising from the distal end of Meckel's diverticulum: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2023;11:e7608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Malligiannis Ntalianis D, Maloula RN, Malligiannis Ntalianis K, Giavopoulos P, Solia E, Chrysikos D, Karampelias V, Troupis T. Anatomical Variations of Vascular Anatomy in Meckel's Diverticulum. Acta Med Acad. 2022;51:243-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mastud K, Lamture Y. Meckel's diverticulum presenting as acute abdomen. Pan Afr Med J. 2023;45:54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Honig J, Figueroa A, Castro R, Lotakis D, Bamji M, Wallack M, Cooper A. Meckel's Diverticulum, A Rare Presentation in a Neonate. Am Surg. 2023;89:2904-2906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Titley-Diaz WH, Aziz M. Meckel Scan. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. |

| 10. | Kuru S, Bulus H, Kismet K, Aydin A, Yavuz A, Tantoglu U, Boztas A, Çoskun A. Mesodiverticular Band of Meckel's Diverticulum as a Rare Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Visc med. 2013;29:401-405. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shirakabe K, Mizokami K. A Case of Torsion of Meckel's Diverticulum. Cureus. 2023;15:e33850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ahmed M, Elkahly M, Gorski T, Mahmoud A, Essien F. Meckel's Diverticulum Strangulation. Cureus. 2021;13:e14817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Hong J, Park SB. A case of retroperitoneal abscess: A rare complication of Meckel's diverticulum. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;41:150-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kohga A, Yamashita K, Hasegawa Y, Yajima K, Okumura T, Isogaki J, Suzuki K, Kawabe A, Komiyama A. Torsion of Atypical Meckel's Diverticulum Treated by Laparoscopic-Assisted Surgery. Case Rep Med. 2017;2017:4514829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saad Eddin A, Chowdhury AJ, Saad Aldin E. Meckel's diverticulum: Unusual cause of significant bleeding in an adult male. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18:3608-3611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |