Published online Feb 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.859

Peer-review started: December 3, 2023

First decision: December 12, 2023

Revised: December 14, 2023

Accepted: January 8, 2024

Article in press: January 8, 2024

Published online: February 6, 2024

Processing time: 52 Days and 21.6 Hours

Mediastinal emphysema is a condition in which air enters the mediastinum between the connective tissue spaces within the pleura for a variety of reasons. It can be spontaneous or secondary to chest trauma, esophageal perforation, medi

A 75-year-old man, living alone, presented with sudden onset of severe epigastric pain with chest tightness after drinking alcohol. Due to the remoteness of his residence and lack of neighbors, the patient was found by his nephew and brought to the hospital the next morning after the disease onset. Computed tomography (CT) showed free gas in the abdominal cavity, mediastinal emph

After gastric perforation, a large amount of free gas in the abdominal cavity can reach the mediastinum through the loose connective tissue at the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm, and upper gastrointestinal angiography can clarify the site of perforation. In patients with mediastinal emphysema, open surgery avoids the elevation of the diaphragm caused by pneumoperitoneum compared to laparoscopic surgery and avoids increasing the mediastinal pressure. In addition, thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia also avoids pressure on the mediastinum from mechanical ventilation.

Core Tip: Abdominal free gas from a perforated gastric ulcer may pass through the lax esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum and then travel up to the neck and chest wall. This condition should be differentiated from esophageal perforation, and upper gastrointestinal angiography can clarify the diagnosis. In such patients, the pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery increases the pressure in the abdominal cavity, not only causing elevation of the diaphragm but also allowing more gas to enter the mediastinum through the esophageal hiatus. Open surgery may be preferred. Thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia can prevent the effect of mechanical ventilation on the mediastinum.

- Citation: Dai ZC, Gui XW, Yang FH, Zhang HY, Zhang WF. Perforated gastric ulcer causing mediastinal emphysema: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(4): 859-864

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i4/859.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.859

The term mediastinum is used for the general name for the right and left mediastinal pleura and the organs, structures, and connective tissue contained within them. The mediastinum includes the heart, large blood vessels that enter and leave the heart, esophagus, trachea, thymus, nerves, lymphatic tissue, etc[1]. The normal mediastinum is free of gas, and mediastinal emphysema is a pathological condition in which gas accumulates in the mediastinum for a variety of reasons. Common causes of mediastinal emphysema include: (1) Alveolar rupture, where gas accumulates in the interlobular septa and diffuses into the mediastinum along the bronchial vascular sheaths; (2) tracheal and esophageal injuries, where air enters the mediastinum; and (3) after neck surgery, gas diffuses into the mediastinum along the cervical fascia space. Mediastinal emphysema due to gastric perforation has rarely been reported[2,3]. Here, we report a case of mediastinal emphysema due to gastric perforation and describe the treatment for this condition.

Epigastric pain with chest tightness after drinking alcohol for 7 h.

A 75-year-old man had a sudden onset of severe epigastric pain for 7 h after drinking alcohol, in addition to chest tightness and shortness of breath.

The patient suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for 15 years.

There was no family history of gastric malignancy or lung malignancy. The patient had smoked for more than 30 years (20 cigarettes/d) and drank alcohol for more than 20 years (50% alcohol, 200 mL/d).

The patient had a painful facial appearance, abdominal distension, full abdominal tenderness, rebound pain, board-like rigidity, and drumming sounds upon percussion in the epigastrium. A palpable crepitus sensation could be observed under the skin of the chest wall. His oxygen saturation measured by finger oximetry (with high-flow oxygen) was 95%.

The patient's liver and kidney function parameters were normal. Blood analysis revealed leukocytosis (13.69 × 109/L) and elevated inflammatory markers, including C-reactive protein (325.9 mg/L), procalcitonin (33.63 ng/mL), and neutrophil percentage (97.4%). The arterial blood gas measurements were as follows: pH = 7.30, PaCO2 = 33 mmHg, PaO2 = 108 mmHg, lactic acid = 3.8 mmol/L, and bicarbonate = 16.8 mmol/L.

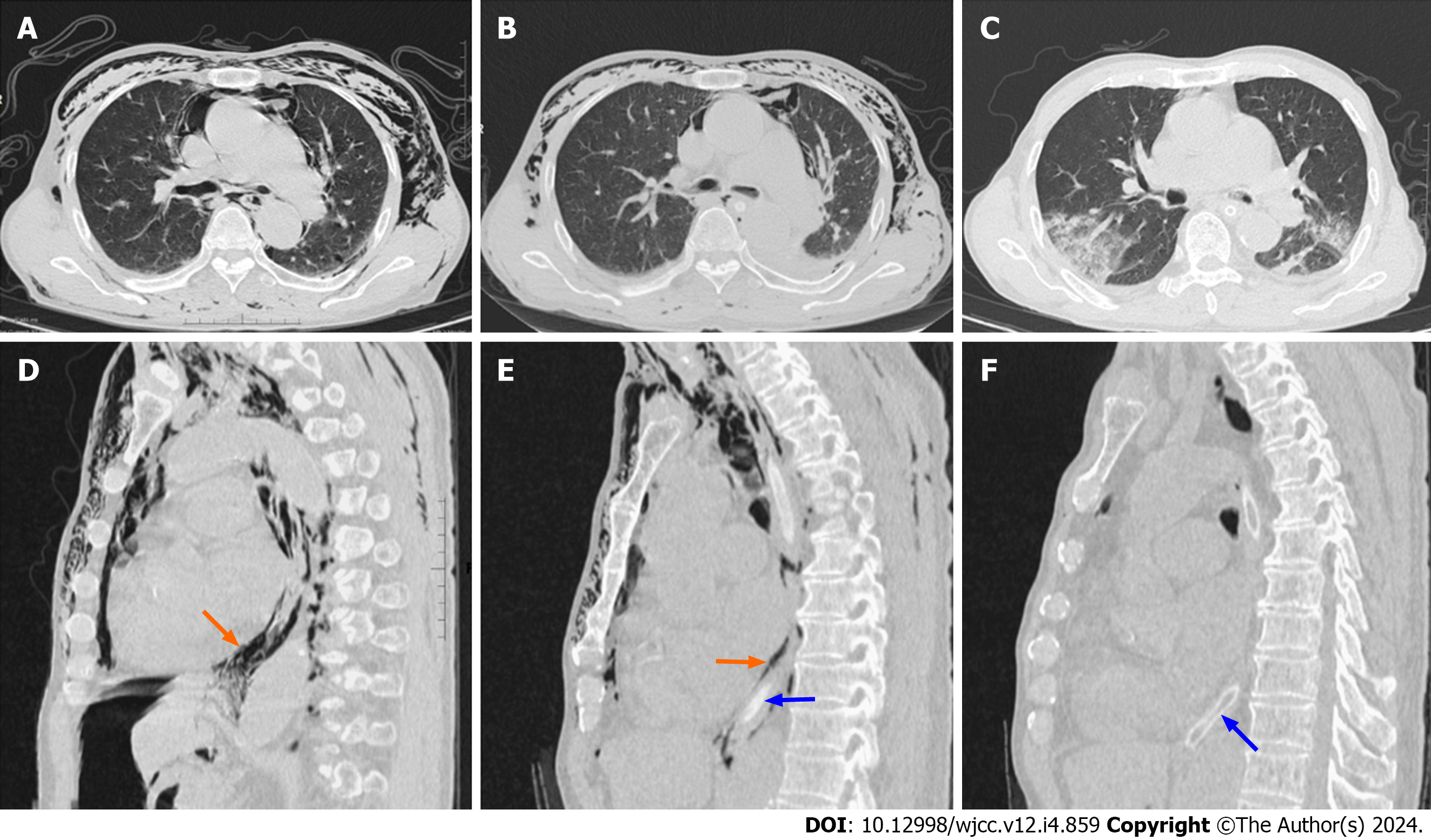

The patient's upper gastrointestinal angiography (contrast medium: Iohexol injection) showed an intact esophageal mucosa and perforation of the gastric antrum (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed free gas in the abdominal cavity, mediastinal emphysema, and subcutaneous pneumothorax (Figure 2A).

Based on imaging findings and clinical symptoms and signs, we could definitively diagnose the patient as having mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema caused by abdominal free gas from the gastric perforation.

We performed open gastric perforation repair under thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia, after which the patient was prohibited from eating and drinking, left with a gastric tube, and received high-flow oxygen. Also, we encouraged the patient to cough. In addition, the patient received acid-suppressing medication (omeprazole sodium 40 mg/12 h) and antibiotics, including cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium 3 g/12 h and metronidazole 0.5 g/12 h.

On the first postoperative day, we performed another chest CT scan and found that the patient's mediastinal and subcutaneous air volume was significantly reduced (Figure 2B). On the third postoperative day, the patient's chest wall twisting sensation was significantly diminished, and his blood parameters also stabilized, including leukocytes (9.69 × 109/L), C-reactive protein (40.9 mg/L), procalcitonin (0.63 ng/mL), and neutrophil percentage (72.4%). The patient underwent another CT examination on the sixth postoperative day, which revealed that the mediastinal emphysema had almost disappeared (Figure 2C). We removed the patient's gastric tube. On the ninth postoperative day, the patient was successfully discharged from the hospital. Postoperative pathology revealed gastric ulcer inflammation. One month later, the patient returned to the hospital for gastroscopy, which showed chronic superficial gastritis and frosted ulcers in the antrum area.

Acute gastric perforation is a common acute abdominal disease in general surgery and is characterized by rapid onset, rapid progression, and severe conditions. If not treated in time, the acidic gastric contents will flow into the abdominal cavity after perforation, and the peritoneum will be stimulated to produce severe abdominal pain. As early as a century ago, gastrointestinal perforation was recognized to cause mediastinal and subcutaneous emphysema. Oetting et al[4] noted that the three most important underlying factors in the pathogenesis of subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema of gastrointestinal origin are intestinal (or gastric) perforation, an adequate pressure gradient between the intestinal lumen and the tissues where the gas ultimately accumulates, and the anatomical site of the perforation. In addition, bacterial infections caused by gastrointestinal perforation may produce some amount of gas and contribute to the development of mediastinal emphysema to varying degrees[5].

In this case, the patient had an acute perforation of a gastric ulcer caused by alcohol consumption; the patient moaned with severe pain and inhaled a large amount of gas into the stomach, and the peristalsis of the stomach prompted the digestive juices and gases in the gastric lumen to pass through the site of the perforation into the abdominal cavity. The abdominal muscles contract violently in response to the stimulation of the digestive juices, thus increasing the pressure in the abdominal cavity and creating a certain pressure gradient within the mediastinum. Elderly people tend to experience widening of the esophageal hiatus and relaxation of the diaphragmatic esophageal membrane. Gas passes through the pressure gradient through the lax part of the esophageal hiatus into the mediastinum, leading to mediastinal emphysema. In addition, the gas in the mediastinum will continue to travel into the neck and chest wall.

A small number of mediastinal emphysema cases can be resolved with conservative treatment, and some of these patients do not even require any management. However, large amounts of mediastinal emphysema in a short period of time can significantly increase the mediastinal pressure, leading to circulatory or respiratory failure, and rapid decompression can be effective at relieving mediastinal pressure[6]. Kiefer et al[7] reported a case in which a patient with a duodenal perforation underwent endoscopy, resulting in a large amount of gas entering the abdominal cavity. Gas entered the mediastinum and subcutaneous tissues through a pressure gradient, and this stagnant air increased the resistance to lung filling and decreased venous return. To relieve pressure on the mediastinum, surgeons used an incision in the clavicle to allow gas to escape, thus restoring normal cardiopulmonary function. Interestingly, this procedure is similar to creating "gills" on the human body. In addition, Herlan et al[8] described four patients with respiratory compromise due to subcutaneous emphysema, in whom respiratory function was normalized by decompression of the subcutaneous emphysema through skin incisions made bilaterally under the clavicle.

Currently, scholars generally agree that laparoscopic surgery is a safe option for the treatment of gastrointestinal perforation. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic surgery is associated with less postoperative morbidity, a lower incidence of wound infection, and shorter hospital stays[9]. However, the creation of pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery increases the pressure in the abdominal cavity, which can compress the diaphragm and displace it into the thoracic cavity, causing narrowing of the mediastinal cavity, increasing the mediastinal pressure, decreasing blood flow, and restricting circulation[10]. Upon admission, the patient's oxygen saturation measured by finger oximetry (with high-flow oxygen) was 95%, and the patient was confirmed to have gastric perforation by imaging. Therefore, we chose to perform open surgery under thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia to relieve the abdominal pressure and break the pressure difference between the abdominal cavity and the mediastinum. During the procedure, when we incised the muscular layer of the abdominal wall, the pressure in the abdominal cavity encourages the peritoneum to expand through the incision. After continuing to incise the peritoneum, a large amount of gas was observed to escape. This confirmed that the peritoneal gas was under high pressure.

An increase in thoracic pressure during mechanical ventilation further exacerbates mediastinal pressure and increases the resistance of venous blood return, leading to a decrease in the amount of venous blood returned to the heart and even causing circulatory failure[11]. In addition, long-term smoking or COPD can make respiratory failure difficult to correct and resolve, resulting in withdrawal difficulties in mechanical ventilation patients. In this case, we chose thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia, and during the operation, the patient experienced auto

In this case, a hasty choice of laparoscopic surgery would have further increased the volume of mediastinal pneumomediastinum, enhanced the pressure in the mediastinal cavity, and jeopardized the patient’s life. Therefore, emergency physicians must be aware that gastric perforation can cause mediastinal emphysema, and such patients can be treated by open surgery under thoracic epidural anesthesia combined with intravenous anesthesia.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vyshka G, Albania S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Ugalde PA, Pereira ST, Araujo C, Irion KL. Correlative anatomy for the mediastinum. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21:251-272, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rizvi S, Wehrle CJ, Law MA. Anatomy, Thorax, Mediastinum Superior and Great Vessels. 2023 Jul 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Weissberg D, Weissberg D. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:885-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oetting HK, Kramer NE, Branch WE. Subcutaneous emphysema of gastrointestinal origin. Am J Med. 1955;19:872-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vonheimburg RL, Alexander SJ, Sauer WG, Bernatz PE. Subcutaneous emphysema from perforated gastric ulcer: Case report and review of literature. Ann Surg. 1963;158:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Smith BA, Ferguson DB. Disposition of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:256-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kiefer MV, Feeney CM. Management of subcutaneous emphysema with "gills": case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:666-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Herlan DB, Landreneau RJ, Ferson PF. Massive spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema. Acute management with infraclavicular "blow holes". Chest. 1992;102:503-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Quah GS, Eslick GD, Cox MR. Laparoscopic Repair for Perforated Peptic Ulcer Disease Has Better Outcomes Than Open Repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:618-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Atkinson TM, Giraud GD, Togioka BM, Jones DB, Cigarroa JE. Cardiovascular and Ventilatory Consequences of Laparoscopic Surgery. Circulation. 2017;135:700-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Singer BD, Corbridge TC. Basic invasive mechanical ventilation. South Med J. 2009;102:1238-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |