Published online Feb 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.842

Peer-review started: October 25, 2023

First decision: December 15, 2023

Revised: December 27, 2023

Accepted: January 15, 2024

Article in press: January 15, 2024

Published online: February 6, 2024

Processing time: 91 Days and 20 Hours

To date, this is the first case of a paradoxical embolism (PDE) that concurrently manifested in the coronary and lower limb arteries and was secondary to a central venous catheter (CVC) thrombus via a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

Here, we report a case of simultaneous coronary and lower limb artery embolism in a PFO patient carrier of a CVC. The patient presented to the hospital with acute chest pain and lower limb fatigue. Doppler ultrasound showed a large thrombus in the right internal jugular vein, precisely at the tip of the CVC. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography confirmed the existence of a PFO, with inducible right-to-left shunting by the Valsalva maneuver. The patient was administered an extended course of anticoagulation therapy, and then the CVC was successfully removed. Percutaneous PFO closure was not undertaken. There was no recurrence during follow-up.

Thus, CVC-associated thrombosis is a potential source for multiple PDE in PFO patients.

Core Tip: Paradoxical coronary embolism is a rare cause of acute myocardial infarction. Here, we report a case of simultaneous coronary and lower limb artery embolism in a patent foramen ovale (PFO) patient carrier of a central venous catheter (CVC). CVC-associated thrombosis is a potential source for paradoxical embolisms in PFO patients. Meanwhile, transesophageal echocardiography can help us detect PFOs more accurately.

- Citation: Li JD, Xu N, Zhao Q, Li B, Li L. Multiple paradoxical embolisms caused by central venous catheter thrombus passing through a patent foramen ovale: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(4): 842-846

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i4/842.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i4.842

Paradoxical embolism (PDE) is a clinical condition characterized by a thromboembolism that originates in the right heart or venous vasculature and travels through an intracardiac or pulmonary shunt into the systemic circulation[1]. The clinical presentation is diverse and potentially life-threatening. In this case, we present a patient with a patent foramen ovale (PFO) who suffered from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and lower limb arterial embolism resulting from a PDE caused by a central venous catheter (CVC)-associated thrombosis.

A 72-year-old female presented to the hospital with acute chest pain and lower limb weakness.

Six days ago, the patient had a CVC implanted for a lumbar disc operation. 6 h before admission, the patient experienced sudden chest pain during the rehabilitation training without shortness of breath or palpitations.

The patient had a medical history of hypertension for 4 years.

No relevant disorders were identified.

Blood pressure was 145/70 mmHg, heart rate was 65 beats/min, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min. Lower limb weakness, without pale and pain and the skin temperature was normal. The pulsation of bilateral dorsal foot arteries was weakened.

The patient’s cardiac biomarkers were elevated, with a high-sensitivity troponin-T level of 0.688 µg/L and a creatine kinase level of 525.3 U/L.

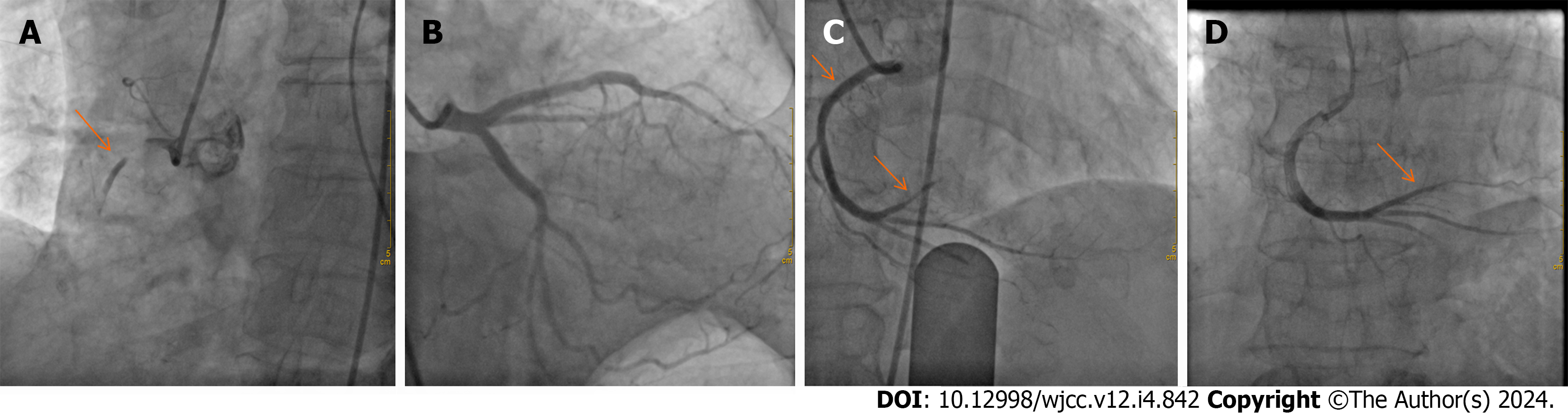

ECG showed sinus rhythm and an ST-segment elevation of 0.1-0.2 mm in the inferior (II, III, and aVF) leads. Emergent coronary angiography (CAG) revealed an acute total occlusion at the proximal segment of right coronary artery (RCA) (Figure 1A), with normal blood flow of the left coronary artery (Figure 1B). After opening the RCA with balloon angioplasty, the repeat angiography revealed a smooth vascular wall without evidence of atherosclerotic plaque (Figure 1C) but the thrombus shattered and moved into the distal of the RCA (Figure 1C). After reperfusion, the patient was administered cardiovascular secondary prevention medication and low-molecular-weight heparin. Doppler ultrasound revealed thrombotic occlusions in the left anterior tibial artery and the right popliteal artery without any evidence of venous thrombosis.

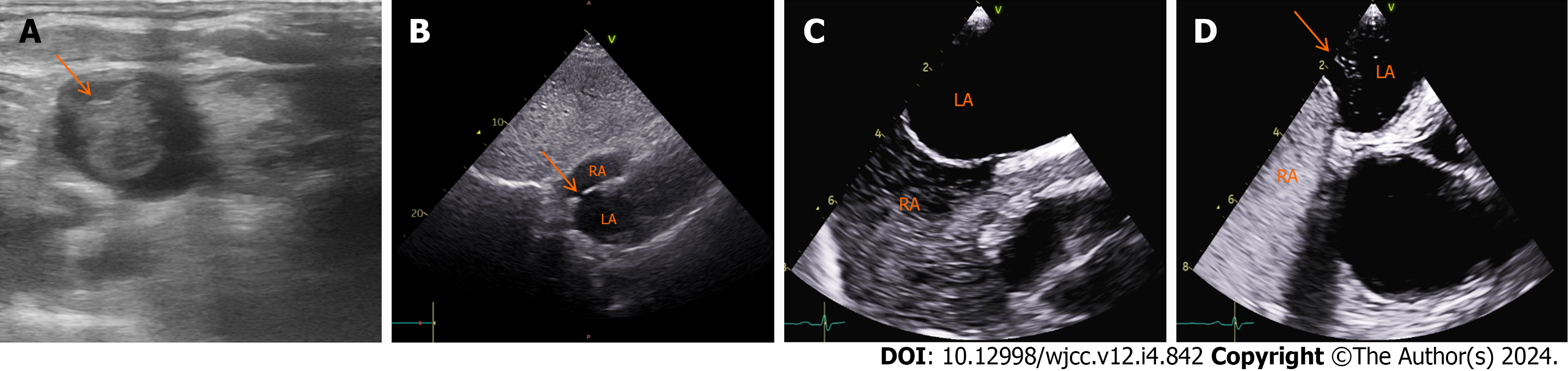

A large thrombus (18 mm × 15 mm × 13 mm) at the tip of the CVC was detected by ultrasound (Figure 2A). A transtho

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was Paradoxical coronary and lower limb arteries embolism caused by CVC-associated thrombosis passing through a PFO.

On the basis of the guideline-based medical therapy for STEMI, the patient was administered an extended course of anticoagulation therapy, specifically low-molecular-weight heparin for seven days, followed by a regimen of apixaban, dosed at 15 mg daily. Before discharge, the CVC was successfully removed.

A follow-up examination conducted two months postdischarge, which included CAG and Doppler ultrasound, indicated successful resolution of the thrombus in the distal region of the RCA (Figure 1D), bilateral limb arteries, and superior vena cava.

The PFO has been identified as a potential source of PDE since the late 19th century and is now recognized as the most common intracardiac shunt in PDE cases[1,2]. The most common sites of PDE are the extremities, accounting for 49% of cases, followed by the cerebrum at 37%. The coronary, renal, or splenic arteries are less frequently affected[3,4]. Instances of PDE resulting in multiple arterial embolisms are rare. Simultaneously, myocardial and renal infarction resulting from a PDE through a PFO was reported[5]. Islam et al[6] reported a case of PDE through a PFO involving the left upper extremity, brain, and coronary artery. However, there have been no reported cases of simultaneous myocardial infarction and lower limb thrombi due to a PDE caused by a CVC-associated thrombosis. This highlights the complexity and variability of PDE and underscores the need for continued research and understanding.

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is often precipitated by coronary atherosclerosis. Despite presenting several risk factors for atherosclerosis, the patient in this case demonstrated a different pathogenesis of AMI. Emergency CAG revealed a thrombotic occlusion in the RCA. After opening the RCA with balloon angioplasty, a repeat angiography of the RCA revealed a smooth vascular wall without evidence of atherosclerotic plaque. Her intact left coronary artery also excluded the presence of coronary atherosclerosis. Hence, we considered that the total occlusion of the RCA is caused by acute thromboembolism rather than chronic due to plaque. Evidence of acute thrombosis was also found in the Doppler ultrasound of the lower limb arteries, where the thrombi had completely disappeared after anticoagulation therapy.

In most cases, the elevated right atrial pressure is secondary to an acute process, such as the Valsalva maneuver, coughing or acute pulmonary embolism with cor-pulmonale or right-sided strain. This permits paradoxical emboli to easily cross the PFO from the right to the left atrium and enter the arterial circulation. Paradoxical emboli have the potential to traverse any branch of the coronary artery via anterograde blood flow, thereby precipitating an AMI. Furthermore, these emboli can disseminate to various organs, including peripheral arteries, resulting in widespread arterial embolisms. In this case, the presence of a small PFO and right-to-left shunting was confirmed through transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and an agitated saline contrast examination. As reported, TEE is the gold standard because it can offer superior sensitivity and precision in detecting atrial anomalies and intracardiac shunts compared to transthoracic echocardiogram[7].

CVC-associated thrombosis constitutes 10% of all deep venous thrombosis (DVTs) in adults and 50%-80% of DVTs among children[8]. In this case, Doppler ultrasound showed the presence of a large thrombus at the tip of the CVC. Brain infarction caused by a CVC-originated paradoxical thrombus was previously reported[9,10]. CVC-associated thrombosis risk factors include catheter material and size, duration of placement, hereditary disorders or hypercoagulable states, blood flow stagnation, and potential endothelial damage from corrosive drugs[8,11]. The most likely risk factor for this case of CVC-associated thrombosis was the extended duration of the CVC placement and potential infection. As suggested by Citla et al[8], it is necessary to continue anticoagulant therapy for at least three months after catheter removal. The EAPCI advises that patients over 65 years of age should be evaluated for PFO closure on an individual basis[12]. In this instance, percutaneous PFO closure was not undertaken due to the PFO’s relatively small size and the potential for eliminating and preventing CVC-associated thrombosis, which was considered the source of the PDE. Considering the patient’s personal preferences, a pharmacological treatment approach was selected.

CVC-associated thrombosis is a potential source for PDE in PFO patients. Examinations for PFO and CVC in unexplained thrombotic events are important to look for possible sources of embolism. Furthermore, TEE can help us detect PFOs more accurately.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jha AK, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Windecker S, Stortecky S, Meier B. Paradoxical embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:403-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hargreaves M, Maloney D, Gribbin B, Westaby S. Impending paradoxical embolism: a case report and literature review. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:1284-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ward R, Jones D, Haponik EF. Paradoxical embolism. An underrecognized problem. Chest. 1995;108:549-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loscalzo J. Paradoxical embolism: clinical presentation, diagnostic strategies, and therapeutic options. Am Heart J. 1986;112:141-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Garachemani A, Eshtehardi P, Meier B. Paradoxical emboli through the patent foramen ovale as the suspected cause of myocardial and renal infarction in a 48-year-old woman. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:1010-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Islam MA, Khalighi K, Goldstein JE, Raso J. Paradoxical embolism-report of a case involving four organ systems. J Emerg Med. 2000;19:31-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Belkin RN, Pollack BD, Ruggiero ML, Alas LL, Tatini U. Comparison of transesophageal and transthoracic echocardiography with contrast and color flow Doppler in the detection of patent foramen ovale. Am Heart J. 1994;128:520-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Citla Sridhar D, Abou-Ismail MY, Ahuja SP. Central venous catheter-related thrombosis in children and adults. Thromb Res. 2020;187:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Batsis JA, Craici IM, Froehling DA. Central venous catheter thrombosis complicated by paradoxical embolism in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis and respiratory failure. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2:185-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Petrea RE, Koyfman F, Pikula A, Romero JR, Viereck J, Babikian VL, Kase CS, Nguyen TN. Acute stroke, catheter related venous thrombosis, and paradoxical cerebral embolism: report of two cases. J Neuroimaging. 2013;23:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jacobs BR. Central venous catheter occlusion and thrombosis. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19:489-514, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pristipino C, Sievert H, D'Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, Gaita F, Toni D, Kyrle P, Thomson J, Derumeaux G, Onorato E, Sibbing D, Germonpré P, Berti S, Chessa M, Bedogni F, Dudek D, Hornung M, Zamorano J; Evidence Synthesis Team; Eapci Scientific Documents and Initiatives Committee; International Experts. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:3182-3195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |