Published online Dec 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i34.6728

Revised: September 11, 2024

Accepted: September 25, 2024

Published online: December 6, 2024

Processing time: 109 Days and 3 Hours

Neuralgic amyotrophy (NA) is a rare disease with sudden upper limb pain followed by affected muscle weakness. The most commonly affected area in NA is the upper part of the brachial plexus, and the paraspinal muscles are rarely affected (1.5%), making these cases difficult to distinguish from cervical radiculopathy.

A 76-year-old male presented to the emergency department with left hip pain post-fall. After undergoing left femoral neck fracture surgery, he experienced sudden left shoulder pain for 10 days with subsequent left arm weakness. Cervical spine computed tomography revealed mild right asymmetric intervertebral disc bulging with a decreased C5-6disc space. Three weeks later, an electrodiagnostic study confirmed brachial plexopathy findings involving the cervical root. Magnetic resonance neurography was performed for a differential diagnosis. Contrast enhancement was identified at the upper trunk of the brachial plexus, including the C5 nerve root. A suprascapular nerve hourglass-like focal con

NA's unique features like HLFC and paraspinal involvement are crucial for accurate diagnosis, avoiding confusion with cervical radiculopathy.

Core Tip: Neuralgic amyotrophy (NA) can closely mimic cervical radiculopathy, leading to potential misdiagnosis. This report presents a 76-year-old male with sudden onset shoulder pain and arm weakness, initially suspected as cervical radiculopathy. Electrodiagnostic studies and magnetic resonance neurography revealed characteristic NA findings, including suprascapular nerve hourglass-like focal constriction. Accurate diagnosis enabled timely treatment with corticosteroids and physical therapy, resulting in significant recovery. This case underscores the importance of distinguishing NA from similar conditions for effective management.

- Citation: Bang MH, Song HL, Hahn S, Kim W, Do HK. Neuralgic amyotrophy with hourglass-like constrictions: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(34): 6728-6735

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i34/6728.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i34.6728

Neuralgic amyotrophy (NA), also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome, is a rare disease characterized by acute onset of upper limb pain followed by affected muscles weakness[1]. The pathophysiology of NA is multifactorial and not completely understood. The interplay between genetic, mechanical and immunological factors is assumed cause NA[1,2].

NA was previously considered a rare disease, with an incidence rate of 1-3 cases per 100000 people yearly. However, recent studies have indicated that NA is frequently misdiagnosed as another musculoskeletal disease due to overlapping symptoms, and its actual incidence is 1 per 1000 people per year[3].

Diagnosing NA is challenging and can often be misdiagnosed as its clinical presentation is like other diseases, including shoulder disorders and cervical radiculopathy. Thus, early identification and accurate diagnosis are critical for preventing mismanagement and improving patient outcomes. Electrodiagnostic as well as imaging studies, patient history and physical examinations, are useful NA diagnostic modalities. Magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) can be help identify nerves affected by NA and demonstrate characteristic NA findings, including hourglass-like focal constriction (HLFC).

This study reports a rare NA case involving the cervical nerve roots. Additionally, we present HLFC findings in a patient who experienced upper extremity motor weakness after sudden-onset shoulder pain.

Left shoulder pain with left arm muscle weakness.

A 75-year-old male presented to the emergency department with left hip pain following a fall. Four days later, he was diagnosed with a left femoral neck fracture and underwent bipolar hemiarthroplasty in the Department of Orthopedic Surgery. The day after surgery, the patient complained of sudden left shoulder pain on a numeric rating scale of 7 points, radiating up to the neck and extending beyond the elbow. After 10 days of left shoulder pain, the patient complained of left arm muscle weakness; however the pain had improved.

The patient had a history of hypertension as an underlying condition and was able to walk independently and perform daily activities prior to the hip fracture.

His personal and family history revealed no additional information relevant to the current case.

The patient complained of hypoesthesia on the lateral side of the left upper arm with atrophy at the left supraspinatus and deltoid muscles. Manual muscle testing (MMT) revealed grade 2 (poor) shoulder abduction and grade 3 (fair) shoulder and elbow flexion. Extension of the left elbow, wrist, and fingers were grade 5 (normal). Deep tendon reflexes of biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis reflexes revealed a normal response. The patient denied any history of trauma or overusing the affected limb prior to symptom onset, with no pathologic findings on shoulder or arm radiographs.

White blood cells, hemoglobin, platelet counts and electrolytes were unremarkable at the time of admission.

Cervical spine computed tomography (CT) was performed to investigate the underlying cause of the left arm weakness. CT scan revealed retrograde spondylolisthesis, mild right asymmetric intervertebral disc bulging, and decreased disc space at the C5-6 level.

Three weeks after symptom onset, an electrodiagnostic study was performed using the Viking Select (Nicolet, San Carlos, CA, United States) to check for neuromuscular lesions. In a nerve conduction study, the compound motor action potentials (CMAPs) of the left musculocutaneous, axillary and radial nerves demonstrated lower amplitudes than those of the right side. However, the left median and ulnar nerve CMAPs demonstrated normal range amplitudes, like those on the right (Table 1). Sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) of the left lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve demonstrated delayed latency, lower amplitude and conduction velocity than those of the right side. The left superficial radial and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves demonstrated lower amplitudes than those of the right side (Table 1). However, the median and ulnar nerves SNAPs revealed normal ranged latency, amplitude, and conduction velocity, similar to those of the right side. Needle electromyography (EMG) demonstrated denervation potentials with reduced volitional motor unit action potentials in the left deltoid, biceps brachii, brachioradialis, infraspinatus, rhomboid major, and cervical paraspinal muscles at the C5 level (Table 2).

| Nerve | Stimulation site | Latency (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Nerve conduction velocity (m/s) | |

| Motor | Rt radial (EIP recording) | Forearm | 2.9 | 6.1 | 56.0 |

| Lateral brachium | 6.3 | 5.9 | |||

| Lt radial (EIP recording) | Forearm | 2.7 | 5.6 | 53.8 | |

| Lateral brachium | 6.0 | 5.0 | |||

| Rt musculocutaneous (biceps recording) | Erb’s Pt | 5.5 | 8.7 | ||

| Lt musculocutaneous (biceps recording) | Erb’s Pt | 5.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Rt axillary (deltoid recording) | Erb’s Pt | 3.5 | 11.2 | ||

| Lt axillary (deltoid recording) | Erb’s Pt | 3.7 | 7.0 | ||

| Sensory | Rt superficial radial | Forearm | 3.0 | 26.1 | 40.3 |

| Lt superficial radial | Forearm | 2.9 | 20.8 | 40.9 | |

| Rt lateral antebrachial cutaneous | Elbow | 1.7 | 18.5 | 42.0 | |

| Lt lateral antebrachial cutaneous | Elbow | 2.1 | 9.6 | 33.6 | |

| Rt medial antebrachial cutaneous | Elbow | 2.3 | 17.5 | 42.9 | |

| Lt medial antebrachial cutaneous | Elbow | 2.2 | 15.8 | 46.2 | |

| Muscle | Insertional activity | Denervation potentials | Polyphasic motor unit action potentials | Interference pattern | |

| Fibrillation potentials | Positive sharp waves | ||||

| Lt deltoid | Increased | 2+ | 3+ | - | Single unit |

| Lt biceps brachii | Increased | 2+ | 3+ | - | Single unit |

| Lt brachioradialis | Increased | 1+ | 2+ | - | Marked reduced |

| Lt triceps brachii | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt flexor carpi radialis | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt extensor digitorum communis | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt first dorsal interosseous | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt abductor pollicis brevis | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt pronator quadratus | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt infraspinatus | Increased | 2+ | 3+ | - | Single unit |

| Lt rhomboid major | Increased | 1+ | 2+ | - | Marked reduced |

| Lt serratus anterior | Normal | - | - | - | Full |

| Lt cervical paraspinalis | Increased | 1+ | 2+ | ||

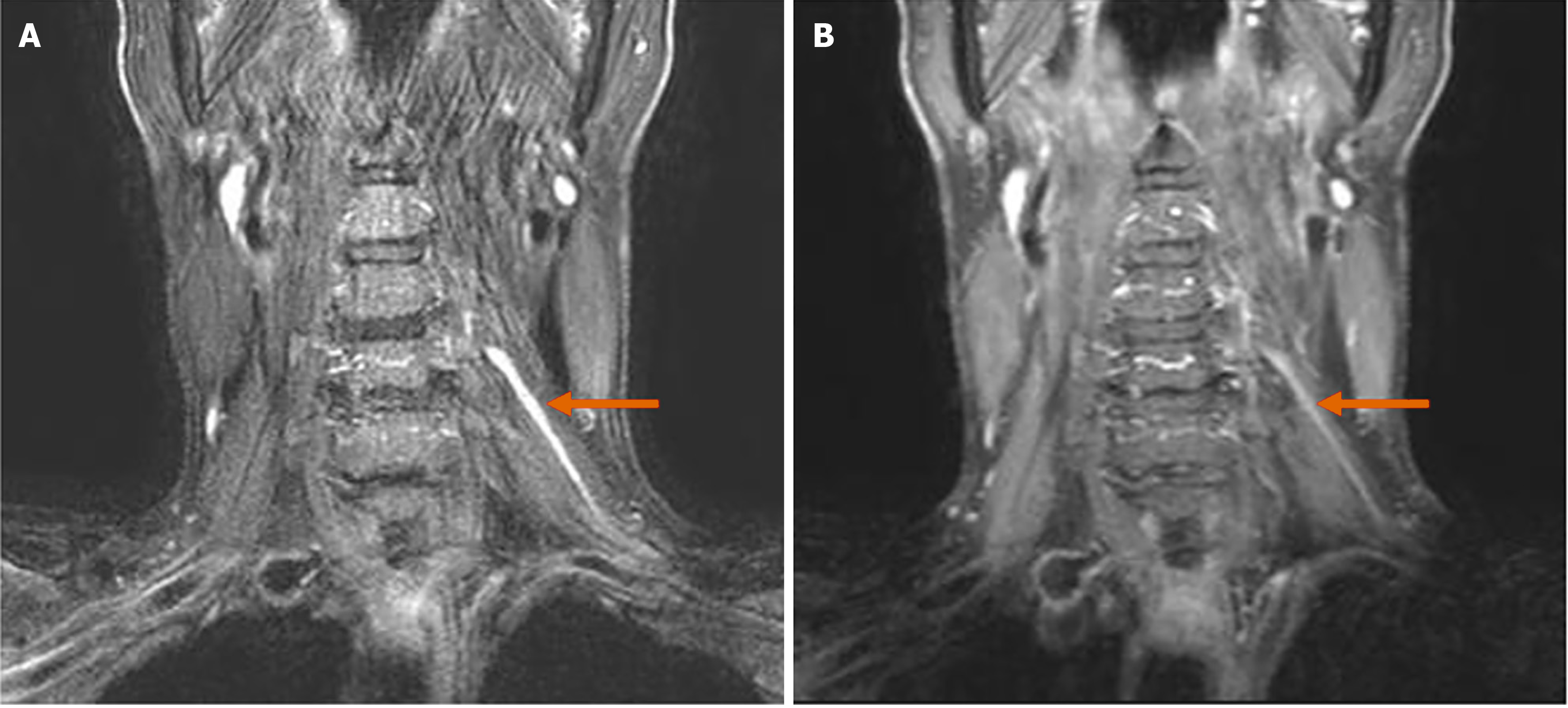

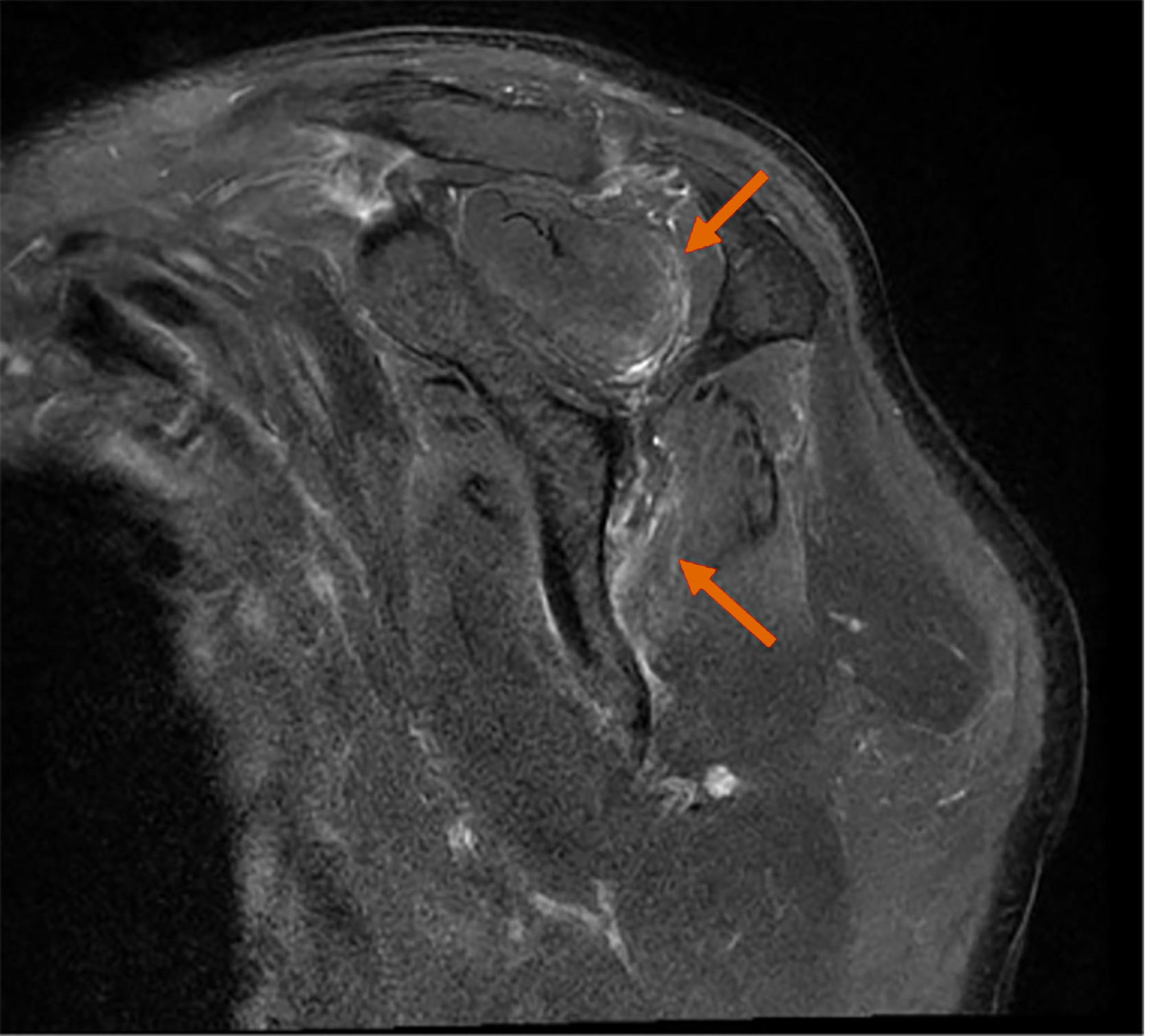

The brachial plexus MRN revealed approximately 6.1 cm of asymmetric thickening and increased signal intensity, with mild contrast enhancement at the left C5 nerve root, trunk, and division levels (Figure 1). Focal thickening and increased signal intensity of the left suprascapular nerve were also noted, along with the identification of HLFC (Figure 2). Additionally, increased signal intensity was observed in the left supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles (Figure 3). No other musculoskeletal abnormalities were found, including any signs of rotator cuff tear or other muscle injuries in the shoulder. Furthermore, there were no pathologic findings suggestive of C5 nerve root compression or impingement. These radiological results were confirmed by a radiologist with extensive experience in neuroradiology.

Considering the previous test results and findings, the patient was diagnosed with a rare case of NA involving the C5 nerve root, accompanied by the HFLC in the suprascapular nerve.

Finally, we identified the patient’s left arm paralysis as a root lesion closely resembling cervical radiculopathy, based on EMG findings. To further clarify the diagnosis, cervical spine CT and MRN were performed. These imaging studies ruled out any issues originating from the spine or other musculoskeletal problems and confirmed that the symptoms were attributable to peripheral neuropathy. Ultimately, the diagnosis of NA involving the C5 nerve root, along with HLFC in the suprascapular nerve, was established.

After the patient was diagnosed with NA, he received 15 mg prednisolone twice daily for 21 days. He also underwent physical and occupational therapies, including left arm strengthening exercises. Desensitization techniques and physical modalities have been applied to manage the tingling sensation, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

One month after treatment, a significant improvement in the physical examination was confirmed in shoulder abduction to MMT grade 3 (fair), shoulder flexion to grade 4 (good), and elbow flexion to grade 4 (good). Two months after treatment, all shoulder strength improved to grade 4 (good), allowing for a return to daily activities.

NA was first described by Dreschfeld in 1887 and is characterized by neuropathic pain attacks and subsequent patchy upper extremity paralysis. Patients with NA experience sudden and severe pain in unilateral shoulder girdle that may radiate to the neck, upper arm, and elbow. The pain reaches its maximum severity over the next few hours and lasts approximately 4 weeks[2]. Muscle weakness may manifest a few days to weeks after the initial symptom onset[4], and the most affected nerves include the axillary, suprascapular, and long thoracic nerves[5].

The pathophysiology mechanism of NA has not been fully elucidated but it involves interactions between genetic, autoimmune, and biomechanical processes. In Idiopathic NA cases, several preceding events have been reported to act as triggers for immune-mediated etiology. According to van Alfen et al[6], 53.2% patients had an antecedent event before a NA attack. Among these patients, infections (43.5%), exercise (17.4%), surgery (13.9%), and peripartum events (8.7%) have been reported as preceding events. In this case, the patient underwent surgery for a hip fracture one day before symptom onset, and this antecedent event could have acted as an immune-mediated etiology.

For an accurate NA diagnosis, a comprehensive medical history and physical examination are crucial. Obtaining a detailed clinical history is essential, including information about symptom onset, severity, pain location, and any factors that worsen symptoms. Additionally, it is important to investigate any underlying factors that may suggest conditions other than idiopathic NA, including previous infections, surgeries, trauma, or other underlying medical conditions.

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine and shoulder is frequently performed in patients with non-traumatic acute unilateral shoulder weakness to visualize denervation-related muscle edema patterns and identify compressive lesions, including a herniated disc, foraminal stenosis, or paralabral ganglion cyst[7]. MRN has recently been used to assess peripheral nerve disorders, enabling nerve enlargement identification and affected nerve signal changes, including the brachial plexus. However, it is important to note that such high signal changes in the brachial plexus and peripheral nerves can also be observed in cervical radiculopathy, possibly limiting the discriminatory value of MRN in distinguishing NA[8]. Fat-suppressed MRI may exhibit a characteristic finding known as the ‘bull’s eye’ sign in HLFC cases, a specific subtype of NA. This sign is characterized by peripheral hyperintensity and central hypointensity on MRN of the affected nerves[7]. Pan et al[9] reported NA cases whereby the intraoperative findings revealed hourglass-like nerve constriction lesions without identifiable visible source of external compression. They proposed that HLFC could be the basic underlying abnormality in brachial neuritis.

Electrodiagnostic examinations are useful for diagnosing NA and determining the location of peripheral nerve involvement. Previous studies have reported abnormal EMG findings consistent with NA in 96.3% of patients[6]. In patients with NA, EMG typically reveals acute denervation findings approximately 3-4 weeks after symptom onset, including positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials in peripheral nerves and their corresponding muscle distribution areas[1]. The most common nerves affected by NA are the suprascapular, axillary, musculocutaneous, long thoracic, and radial. Other nerves may include the anterior as well as dorsal interosseous, lateral antebrachial cutaneous, phrenic, and axillary nerves[6,10]. Paraspinal abnormalities can be observed on needle EMG, making it challenging to differentiate NA from a cervical radiculopathy[11]. Studies have reported that approximately 47% patients with cervical radiculopathy exhibit abnormal spontaneous potentials on needle EMG examinations of the cervical paraspinal muscles. However, only 1.5% patients with NA demonstrate an abnormal spontaneous potential[6]. The paraspinal muscles are usually spared in NA because brachial plexus root involvement is uncommon[12]. However, in our case, abnormal spontaneous potentials were observed in the paraspinal muscles on needle EMG and enhancement at the C5 root level was observed on MRN. This finding makes it difficult to differentiate between cervical radiculopathy and NA. However, the HFLC sign was observed on MRN, a characteristic NA finding. Additionally, MRI revealed no compressive lesions at the cervical root level. Based on these findings, the final diagnosis was NA.

Silverman et al[12] reported a case in which MRI and EMG findings were consistent with cervical radiculopathy in a patient presenting with clinical features of NA. Because NA and cervical radiculopathy can present with overlapping clinical histories and imaging results, relying solely on EMG or MRI may lead to diagnostic confusion. Therefore, it is essential to perform additional imaging studies, such as MRN, to achieve an accurate diagnosis.

The most effective pain treatment in the early stages of NA is a combination of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications and slow-release opiates. Although many studies have reported the potential corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin effectiveness during the acute phase of NA, long-term corticosteroids recovery effects have not been proven[13,14]. Neuroimaging evaluation using MRI or high-resolution ultrasound is recommended if no clinical improvement is observed for more than three months, and surgical intervention may be considered if constriction is confirmed.

Physical therapy plays an important role in NA treatment. NA can cause muscle weakness and wasting, which can cause joint dysfunction and instability of the affected limb. Therefore, rehabilitation therapy to prevent joint contracture and maximize biomechanical stability may be more beneficial than general muscle strengthening[1].

The course and prognosis of NA can vary significantly. Approximately 80%-90% patients recover to their previous state within about 2-3 years of onset, but approximately 70% may experience residual muscle weakness. Continuous pain without muscle recovery 3 months from onset is associated with a poor prognosis[2,6]. Patients with upper trunk involvement have a better prognosis than those with lower trunk involvement. Furthermore, pain duration generally correlated with muscle weakness duration. In this case, imaging studies revealed upper trunk involvement of the brachial plexus and muscle strength recovery after one month of oral steroid treatment.

Numerous NA cases had been reported whereby early administration of corticosteroids or other immune-modulating therapies could have favorable effects on pain and prognosis[6,13]. Therefore, an accurate and prompt NA diagnosis is essential, and various diagnostic assessments should be performed, including MRI and EMG.

NA, involving the cervical nerve root and HLFC finding, is rare and may be misdiagnosed as cervical radiculopathy in electrodiagnostic studies. As NA demonstrates various clinical features and involves various nerves, it is important to accurately diagnose through physical examination, electrodiagnostic studies, and imaging studies, including MRN. Early treatment with a prompt and accurate diagnosis will have a positive effect on the patient functional prognosis.

| 1. | Tjoumakaris FP, Anakwenze OA, Kancherla V, Pulos N. Neuralgic amyotrophy (Parsonage-Turner syndrome). J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:443-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van Alfen N. Clinical and pathophysiological concepts of neuralgic amyotrophy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Alfen N, van Eijk JJ, Ennik T, Flynn SO, Nobacht IE, Groothuis JT, Pillen S, van de Laar FA. Incidence of neuralgic amyotrophy (Parsonage Turner syndrome) in a primary care setting--a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feinberg JH, Radecki J. Parsonage-turner syndrome. HSS J. 2010;6:199-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bowen BC, Pattany PM, Saraf-Lavi E, Maravilla KR. The brachial plexus: normal anatomy, pathology, and MR imaging. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2004;14:59-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | van Alfen N, van Engelen BG. The clinical spectrum of neuralgic amyotrophy in 246 cases. Brain. 2006;129:438-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim DH, Kim J, Sung DH. Hourglass-like constriction neuropathy of the suprascapular nerve detected by high-resolution magnetic resonance neurography: report of three patients. Skeletal Radiol. 2019;48:1451-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schwarz D, Kele H, Kronlage M, Godel T, Hilgenfeld T, Bendszus M, Bäumer P. Diagnostic Value of Magnetic Resonance Neurography in Cervical Radiculopathy: Plexus Patterns and Peripheral Nerve Lesions. Invest Radiol. 2018;53:158-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pan YW, Wang S, Tian G, Li C, Tian W, Tian M. Typical brachial neuritis (Parsonage-Turner syndrome) with hourglass-like constrictions in the affected nerves. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1197-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sumner AJ. Idiopathic brachial neuritis. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:A150-A152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | IJspeert J, Janssen RMJ, van Alfen N. Neuralgic amyotrophy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2021;34:605-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Silverman B, Shah T, Bajaj G, Hodde M, Popescu A. The Importance of Differentiating Parsonage-Turner Syndrome From Cervical Radiculopathy: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14:e28723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Alfen N, van Engelen BG, Hughes RA. Treatment for idiopathic and hereditary neuralgic amyotrophy (brachial neuritis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD006976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gstoettner C, Mayer JA, Rassam S, Hruby LA, Salminger S, Sturma A, Aman M, Harhaus L, Platzgummer H, Aszmann OC. Neuralgic amyotrophy: a paradigm shift in diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91:879-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |