Published online Dec 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i34.6715

Revised: September 11, 2024

Accepted: September 25, 2024

Published online: December 6, 2024

Processing time: 174 Days and 23.7 Hours

The tear of the gluteus medius and minimus tendons can cause chronic buttock pain, especially in middle-aged individuals; these tears occur mostly in asso

The authors present a case of bilateral acute traumatic injuries to the gluteus minimus during buttock strengthening exercises in a 75-year-old male patient. The patient completely returned to his pre-injury lifestyle after 8 weeks of injury, with no limitations, but the diagnosis was initially delayed due to misdiagnosis as lumbar radiculopathy, resulting in unnecessary socio-economic burden on the patient.

When treating patients who complain of hip pain, it is important to consider various causes to make a correct diagnosis.

Core Tip: Most cases of gluteus minimus damage occur together with damage to the medius due to trauma; when damaged alone, it is associated with degenerative changes. The authors report a case of a patient with bilateral gluteus minimus traumatic injury. In this extremely rare case, the patient was not diagnosed early and was misdiagnosed with lumbar neuropathy. As body-specific exercises become more popular, it is important to note that although rare, isolated muscle damage is possible. This case can inform future clinicians to aid in timely and correct diagnosis.

- Citation: Cho HM, Heo H, Jung MC. Traumatic isolated bilateral gluteus minimus injuries misdiagnosed as lumbar radiculopathy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(34): 6715-6720

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i34/6715.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i34.6715

Injuries to the major external rotators of the hip, the gluteus medius and minimus muscles, are uncommon; when they occur, they are primarily associated with chronic conditions such as arthritis or degenerative changes, especially in middle-aged patients[1]. Acute or traumatic isolated injuries to the gluteus medius alone or in conjunction with the gluteus minimus are very rarely reported[2]. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of bilateral gluteus minimus injuries occurring solely due to trauma.

With the recent emphasis on the importance of muscle and strength for a healthy lifestyle, there has been a trend towards specialized exercises targeting specific muscles and muscle groups. However, injuries to muscles that may occur due to targeted exercises can be overlooked if a thorough assessment is not conducted. The authors experienced a case of bilateral gluteus minimus injuries occurring during buttock strengthening exercises. The patient presented with symptoms similar to sciatic nerve pain due to lumbar radiculopathy, leading to oversight of an injury to the gluteus minimus, resulting in unnecessary tests and treatments and causing discomfort and economic loss to the patient.

Considering the recent trend of targeted strength training exercises, it is important to recognize that uncommon muscle injuries can occur when patients present with pain during exercise. Therefore, the authors believe that a thorough examination, including detailed questioning about the activities performed, is necessary to identify potential sites of injury. With this in mind, we report our findings along with a review of the literature, emphasizing the importance of accurate assessment in cases where exercise-related pain is reported.

A 75-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with symptoms of pain in both buttocks posteriorly and difficulty walking during exercise.

The patient complained, "The area below my waist and around both hip hurts, and it feels like my legs are weak". Symptoms occurred suddenly during lower limb exercise, with no notable history of falls or trauma.

The patient had no history of acute or chronic infectious diseases, heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, or surgery.

The patient had no relevant family medical history.

Neurological examination revealed no sensory deficits in the lower limbs, and muscle strength in the hip, knee, and ankle joints was within normal range. There was no significant tenderness, but the patient complained of pain in the lower lumbar region and both buttocks posteriorly and laterally, as well as pain in both thighs posteriorly, with no notable radiation below the knees. Pain in both thighs posteriorly worsened with straight leg raising tests. The pain severity was rated as 6 on the visual analog scale (VAS), making it difficult for the patient to stand and preventing him from turning his body while lying down due to pain. The patient had a medical history of hypertension and diabetes but was not taking any medication that could affect blood clotting. On physical examination, body temperature was normal, with no rash or warmth on the skin.

Blood tests revealed a white blood cell count of 7100/μL and erythrocyte sedimentation rate/C-reactive protein of 12 mm/0.03 mg/dL, all within normal ranges.

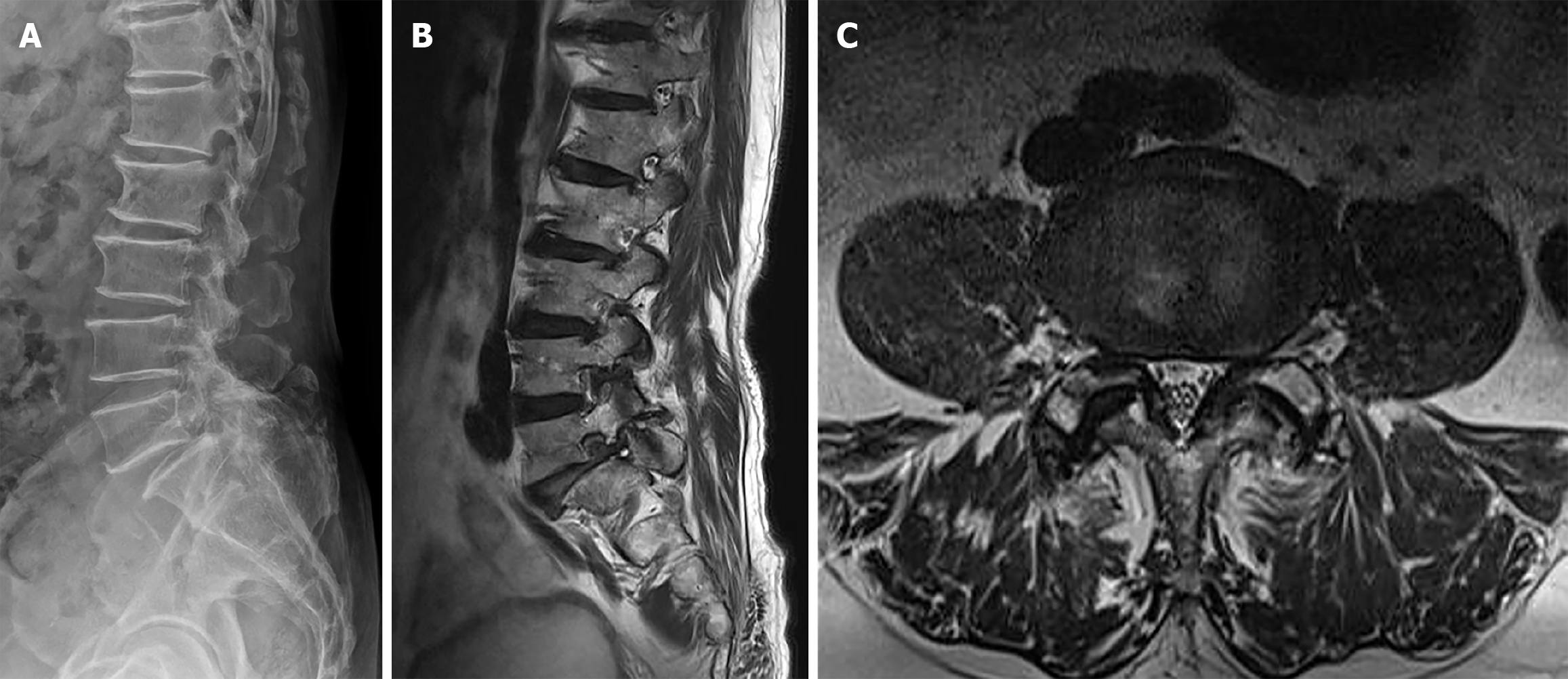

General radiological examination revealed degenerative changes in the lower lumbar (L) spine, intervertebral disc herniation at L4-L5, and anterior spondylolisthesis, as well as instability confirmed on lateral imaging after flexion and extension views of the lumbar spine (Figure 1A). No specific findings were noted on general radiological examination of the pelvis and hip joints. Suspecting sciatic nerve pain due to lumbar radiculopathy, further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine was performed. MRI revealed intervertebral disc herniation and spondylolisthesis at L4-L5, along with bilateral foraminal stenosis between L5 and S1, raising suspicion of sciatic nerve pain due to L5 radiculopathy (Figure 1B). The patient was subsequently admitted for further management after consultation with the orthopedic spine center.

On the first day of admission, a bilateral L5 selective root block was performed for the L5 nerves, along with bed rest and administration of analgesics, anti-inflammatories, and muscle relaxants. At the time of admission, the patient complained most severely of pain and weakness in the legs, but 3 days after the procedure, he reported a slight improvement in buttock pain compared with before the procedure (VAS score: 4), although there was no significant improvement in leg weakness. Therefore, on the 7th day of admission, bilateral neuroplasty at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 Levels was additionally performed. Neuroplasty involved injecting 1% lidocaine 5 mL followed by 10 mL of saline, then a mixture of 0.25% bupivacaine 2.25 mL and saline 7.75 mL, followed by injection of 10% hypertonic saline. On the 11th day of admission, due to no significant improvement in buttock pain after neuroplasty (VAS score: 4), ultrasound-guided medial branch block was performed bilaterally at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 Levels, and 0.5% lidocaine 5 mL was injected per branch. However, the patient still reported feeling weakness in the legs, similar to that at the time of admission. On the 14th day of admission, buttock pain gradually improved (VAS score: 2), and the patient was discharged. Although buttock pain had improved since the time of admission, there was no change in the complaint of leg weakness. The spine center recommended conservative treatment, including 2 weeks of outpatient physical therapy, and explained the possibility of future decompression and fixation surgery for the L5 and S1 Levels if there was no improvement in symptoms (Figure 1C).

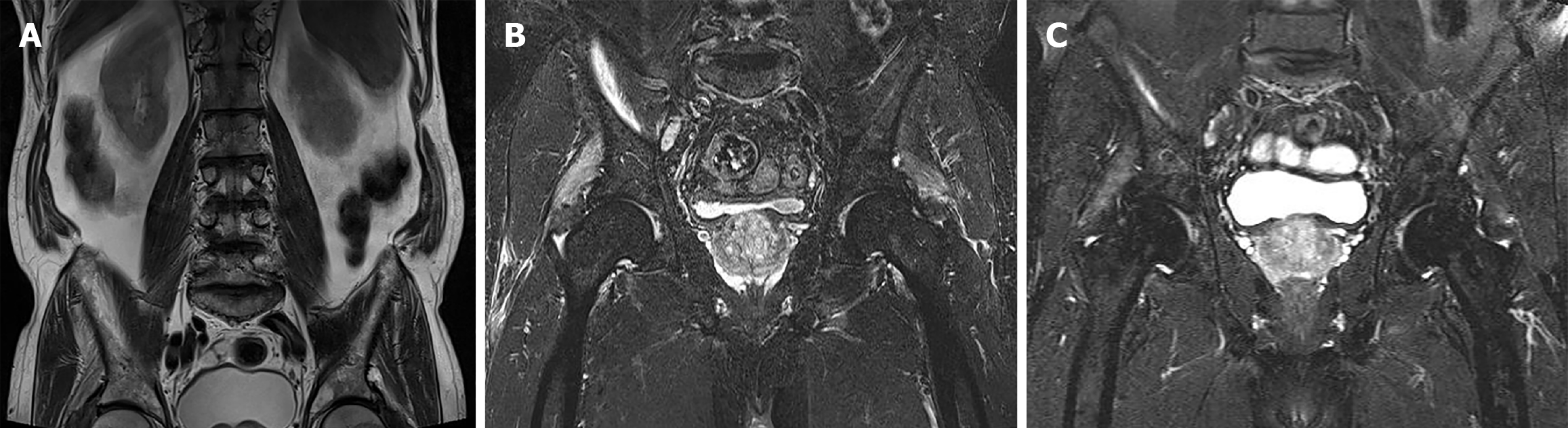

Precisely 1 week after discharge (3 weeks post-injury), the patient visited the orthopedic joint center of the hospital, complaining of leg weakness, saying, "I can't walk properly". Along with a physical examination, the imaging from the spine center during admission was reviewed. The physical examination raised suspicion of pain and muscle weakness during active external rotation of both hip joints, and abnormal findings of the gluteus minimus muscles were observed on the coronal images included in the lumbar MRI examination (Figure 2A). Additional MRI examination of both hip joints was performed, revealing high signal intensity areas in the gluteus minimus on T2-weighted images of the coronal plane, along with a small amount of fluid accumulation around the greater trochanter and evidence of partial tearing of the gluteus minimus attachment (Figure 2B).

The patient was further interviewed to determine the specific movements that caused pain during the injury. The patient reported engaging in lower body exercises at the time of injury, with a focus on buttock strengthening exercises. Particularly during the episode of severe pain, the patient was performing specialized exercises targeting the gluteus medius and minimus muscles, involving lying down with resistance bands wrapped around the ankles and externally rotating and abducting both legs.

No specific treatment was administered thereafter, and the patient was advised to refrain from exercise for 4 weeks. Subsequently, symptoms gradually improved, and by the final follow-up at 8 weeks post-injury, the patient reported no discomfort and was able to resume daily activities without any issues.

Follow-up MRI scans of both hip joints showed significant improvement in the previously damaged gluteus minimus compared to the initial images, indicating recovery (Figure 2C). Therefore, at 3 months post-injury, the patient returned to exercise and discontinued follow-up appointments.

The gluteus medius and minimus muscles are the major external rotators of the hip joint. When these muscles are injured, it can result in pain around the outer aspect of the hip joint and weakness in external rotation. Such injuries are commonly observed in female patients aged 40−60, often associated with a history of trauma, arthritis, or obesity, which are known contributing factors to muscle tears. According to research by William et al[3], changes in the shape, size, and orientation of the pelvis (such as anteversion or retroversion) or biomechanical changes in the pelvic ligaments can increase the risk of injury[3]. Among these, the gluteus medius is the most commonly injured due to trauma. Yanke et al[4] reported that when gluteus medius injuries occur, the gluteus minimus is often also involved, suggesting that degenerative changes in muscle and tendon structures may be contributing factors[4]. However, isolated injuries to the gluteus minimus are extremely rare and typically occur due to trauma, although natural recovery is possible.

The gluteus minimus muscle has a broad, fan-shaped structure and originates from the outer surface of the ilium, forming two distinct attachments. One attachment is in the form of a tendon, attaching to the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter, while the other attachment is in the form of a fascia or thin muscle, attaching to the anterior aspect of the hip joint capsule. Along with the gluteus medius, the gluteus minimus contributes to the stability of the pelvis during walking. The main tendon of the gluteus minimus, attached to the anterior aspect of the greater trochanter, plays a role in flexion, external rotation, and abduction of the hip joint, depending on the position of the femoral head. The part attached to the hip joint capsule aids in tightening the capsule, contributing to stabilizing the femoral head by exerting compressive pressure on the intracapsular femoral head[5].

The gluteus minimus is the smallest and deepest of the three gluteal muscles, and if injured in isolation, patients may complain of vague buttock pain without accurately pinpointing the location. Identifying precise tender points during physical examination can also be challenging. Pain resulting from anterior gluteus minimus injury may manifest as pain descending from the lateral aspect of the buttock to the side of the thigh, resembling the pain pattern of L5 nerve root compression. Conversely, pain from posterior gluteus minimus injury may start from the lower inner buttock and extend to the back of the thigh and calf, mimicking symptoms of S1 nerve root compression. Consequently, overlooking the primary lesion of gluteus minimus injury and suspecting lumbar nerve root compression based on the patient's pain complaints may occur. Additionally, patients with gluteal external rotator muscle injuries may present with buttock weakness and pain, exacerbated by prolonged standing, stair climbing, or standing on the affected leg[6], which may resemble the Trendelenburg gait pattern. However, the Trendelenburg gait can also occur in patients with lumbar nerve root compression, making it even more challenging to differentiate[7]. In our case, although the patient complained of buttock and hip pain, identifying the exact tender points was difficult, and pain persisted even during rest, with exacerbation upon hip joint stress testing, leading to initial suspicion of lumbar nerve root compression.

Acute traumatic minimus tears are rare. Due to the nonspecific and slowly progressing symptoms, patients are often misdiagnosed with radiculopathy, osteoarthritis, or trochanteric bursitis. Patients typically present to the clinic with complaints of pain at the lateral aspect of the hip, reduced hip abduction strength, and limitations in performing physical activities requiring hip movements, especially in the lateral decubitus position, and certain gluteal-focused movements such as climbing stairs that may exacerbate the pain. This presentation is similar to that of trochanteric bursitis; however, considering the reduced hip abduction strength, gluteus minimus or medius tears could be a cause. On physical examination, patients often have reproducible tenderness on palpation of the greater trochanter and pain during resisted hip abduction. Additionally, in our case, the presenting symptoms and physical examination related to the motion and strength of the hip joint were indicative of gluteus minimus muscle damage rather than radiculopathy.

Health-related discussions emphasize the importance of muscle mass and strength levels, as maximal strength and muscle endurance induced by strength training positively impact cardiovascular function, body balance, range of motion, and movement speed, among other physical abilities[8]. Recently, there has been considerable interest in weight resistance training for maintaining a healthy and active lifestyle and self-care. However, the choice of exercise method and intensity during weight resistance training may be associated with various factors, such as the anatomical characteristics and biomechanical status of the individual, potentially posing risks of injury. Musculoskeletal pain and injury risks can arise not only from improper positioning but also from overuse, inadequate recovery between exercises, improper form, and high loads or frequency of exercises[9]. Exercises that target specific body parts for concentrated strengthening may lead to damage to anatomical structures. In our case, although it involved a very rare injury, the patient incurred injuries while performing gluteus minimus strengthening exercises with elastic bands around both ankles during localized weight resistance training. Despite the patient's knowledge of the specific muscle strengthening exercises that triggered the injury, failure to conduct a thorough history-taking regarding the injury process led to the initial suspicion of lumbar nerve root compression due to sudden-onset lower back pain and buttock and thigh pain during lower body exercises, imposing unnecessary social and economic burden on the patient.

With the advancement in medical technology, specialization in orthopedic surgery is becoming increasingly refined and detailed. Among these, doctors specializing in hip joints and those focusing on the spine tend to prioritize their respective fields when considering the causes of hip pain. However, hip pain can stem from various factors beyond neurogenic disorders associated with the spine, including superior gluteal nerve entrapment, lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy, and other neural-related causes. Additionally, there can be multiple anatomical structures contributing to hip pain, such as injury of ligaments, labrum, or tendons, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, intra-articular loose bodies, as well as extra-articular factors like piriformis syndrome, impingement syndrome, and tumors[10]. Therefore, a diagnostic approach considering multiple possible causes is necessary.

When dealing with patients complaining of hip joint pain, it is essential to approach the diagnosis with a wide range of possibilities and consider various causes. If the distinction is unclear, imaging examinations that include the lumbar spine and hip joint may be beneficial for confirmation. As in this case, understanding the circumstances and conditions surrounding the injury can aid in diagnosis. Therefore, a thorough and meticulous history-taking approach should not be overlooked, as it can provide valuable insights into the patient's condition.

| 1. | Domb BG, Gui C, Lodhia P. How much arthritis is too much for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:520-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Godshaw B, Wong M, Ojard C, Williams G, Suri M, Jones D. Acute Traumatic Tear of the Gluteus Medius and Gluteus Minimus in a Marathon Runner. Ochsner J. 2019;19:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Williams BS, Cohen SP. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: a review of anatomy, diagnosis and treatment. Anesth Analg. 2009;108:1662-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yanke AB, Hart MA, McCormick F, Nho SJ. Endoscopic repair of a gluteus medius tear at the musculotendinous junction. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2:e69-e72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dwek J, Pfirrmann C, Stanley A, Pathria M, Chung CB. MR imaging of the hip abductors: normal anatomy and commonly encountered pathology at the greater trochanter. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2005;13:691-704, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bajuri MY, Sivasamy P, Simanjuntak GRN, Azemi AF, Azman MI. Posttraumatic Isolated Right Gluteus Minimus Tear: A Case Report. Cureus. 2022;14:e23056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fisher DA, Almand JD, Watts MR. Operative repair of bilateral spontaneous gluteus medius and minimus tendon ruptures. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1103-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chaabene H, Prieske O, Negra Y, Granacher U. Change of Direction Speed: Toward a Strength Training Approach with Accentuated Eccentric Muscle Actions. Sports Med. 2018;48:1773-1779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bonilla DA, Cardozo LA, Vélez-Gutiérrez JM, Arévalo-Rodríguez A, Vargas-Molina S, Stout JR, Kreider RB, Petro JL. Exercise Selection and Common Injuries in Fitness Centers: A Systematic Integrative Review and Practical Recommendations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Howell GE, Biggs RE, Bourne RB. Prevalence of abductor mechanism tears of the hips in patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:121-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |