Published online Nov 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i31.6462

Revised: June 14, 2024

Accepted: August 20, 2024

Published online: November 6, 2024

Processing time: 221 Days and 8.8 Hours

Pancreatic resection is still associated with high morbidity rates and delayed postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) is the most feared complication as it may lead to hemorrhagic shock or serious septic complications. Today, endovascular approach represent safe and efficient method for minimally invasive management of extraluminal PPH.

We describe four patients whose postoperative recovery after pancreatic resection was complicated by postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and visceral artery hemorrhage. In all cases endovascular approach was utilized and it resulted in satisfactory outcomes. We discuss modern diagnostic and therapeutic approach in this clinical scenario.

PPH is relatively uncommon, but it is a leading cause of surgical mortality after pancreatic surgery. Careful monitoring and meticulous follow-up are required for all patients post-operatively, especially in the case of confirmed POPF, which is the most significant risk factor for the development of a PPH. Angiography as a diagnostic and therapeutic method may be an optimal first-line treatment for the management of delayed PPHs. In our experience, endovascular treatment for hemorrhagic complications of pancreatic resections has shown sa

Core Tip: Pancreatic resections are associated with specific complications and most feared one is hemorrhage due to erosion of large peripancreatic vessels. It is rare, but serious clinical scenario which should be considered in all cases of post

- Citation: Petrovic I, Romic I, Alduk AM, Ticinovic N, Koltay OM, Brekalo K, Bogut A. Delayed postpancreatectomy hemorrhage as the role of endovascular approach: Four case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(31): 6462-6471

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i31/6462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i31.6462

Pancreatic resection is a complex procedure, and despite recent advances in techniques and perioperative care, it is still associated with a high complication rate. The most common complications are intra-abdominal infections and pancreatic fistulas. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) is relatively rare (incidence between 2% and 8%), but it represents a life-threatening complication associated with a high mortality rate[1]. To overcome confusion regarding the definition of PPH, in 2007, an international study group on pancreatic surgery suggested standardization of the definition and pro

Location of bleeding is either intraluminal or extraluminal, while its severity can range from mild to severe, depending on factors such as volume of blood loss, clinical impairment, and the need for surgical reintervention or interventional angiographic embolization. In addition, the clinical grading system of PPH with grades A, B and C was proposed: PPH grade A has no major impact on standard postoperative care, and length of hospital stay, while PPH grade B always requires further diagnostics and will lead to therapeutic consequences such as the need for blood transfusion or the need for reintervention. PPH grade C refers to life-threatening bleeding requiring immediate diagnostics and therapy and it invariably leads to an extended hospitalization period and frequently requires admission to intensive care units (ICU).

PPH can manifest in several clinical presentations, and depending on its location, it can be intraluminal or extraluminal[3]. Intraluminal PPH is defined as the occurrence of blood draining via the nasogastric tube, hematemesis, or melena, while extraluminal PPH is characterized by the presence of blood in abdominal drains or when hematoperitoneum is detected intraabdominally via radiologic tests. Sentinel bleed is specific category of bleeding defined as minor blood loss via surgical drains or the gastrointestinal tract. It is generally asymptomatic, but its significance lies in the fact that after asymptomatic interval, hemorrhagic shock may develop, therefore sentinel bleed may be alert for potentially more serious bleeding from PSAN or vascular erosions[4].

Diagnostic and treatment options include early computed tomography (CT) with angiography, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, interventional angiography and relaparotomy[5]. Diagnostic angiography including digital subtraction angiography (DSA) may localize the bleeding site, and thereafter an embolization can be performed. When it is not technically feasible or when massive bleeding is present, a surgical re-exploration may be needed. Surgery is also indi

In this article, we report four patients whose postoperative recovery after pancreatic resection was complicated by postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and visceral artery hemorrhage (Table 1). Two patients underwent distal pancreatectomy, one underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure), and another underwent the excision of an insulinoma. All patients experienced late PPH, a serious complication requiring prompt diagnosis and treatment, most commonly in the form of endovascular visceral artery embolization. Satisfactory resolution after endovascular treatment was achieved in all four cases.

| Patient/Sex/Age | Diagnosis | Operation | Bleeding POD | Bleeding location | PSAN | PSAN size | Pancreatic fistula | Fistula grade | Bleeding presentation | Treatment |

| Case 1/F/52 | Insulinoma | Insulinoma enucleation | 7 | GDA | - | - | + | B | Hypotension and febrile state | Endovascular GDA embolization, relaparotomy |

| Case 2/M/46 | Chronic pancreatitis | Pancreato-duodenectomy | 16 | GDA | + | 7 mm | + | B | Abdominal pain, drainage tube hemorrhage | Relaparotomy, endovascular GDA embolization |

| Case 3/M/82 | Neuroendocrine tumor | Spleen preserving pancreatectomy | 57 | SA | + | 14 mm | + | B | Hematemesis, abdominal pain | Endovascular SA embolization, CT guided drainage |

| Case 4/F/62 | Insulinoma | Pancreato-duodenectomy (Whipple) | 43 | SA | + | 18 mm | + | B | Hematemesis | Endovascular SA embolization |

Case 1: A 52-year-old woman complained of hypoglycemia (blood glucose level of < 2.0 mmol/L), persistent nausea, and blurred vision for 4 weeks.

Case 2: A 46-year-old man presented with recurrent episodes of pancreatitis, most likely caused by pancreas divisium, which was confirmed through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Case 3: An 82-year-old man had routine ultrasound check up that discovered pancreatic nodule located in the pancreatic tail.

Case 4: A 62-year-old female presented with episodes of hypoglycemia and flushing for 4 months.

Case 1: The patient developed refracted hypoglycemia and generalized weakness that progressed over 4 weeks. She had no specific abdominal symptoms.

Case 2: The patient experienced intermittent colicky pain in the upper abdomen associated with nausea and weight loss over the 6 months period.

Case 3: The patient was asymptomatic.

Case 4: The patient visited general practitioner for evaluation of flushing and hypoglycemia. She experienced these symptoms for 4 months.

Case 1: She had previous history of arterial hypertension and hypothyroidism.

Case 2: No significant past history or any illness or surgery.

Case 3: He had cholecystectomy 4 years ago and chronic renal insufficiency.

Case 4: She had uterine fibroids and arterial hypertension.

Case 1: Physical examination showed no specific abnormalities.

Case 2: Physical examination showed slightly tender upper abdomen.

Case 3: The physical examination was normal.

Case 4: The patient was obese, but had no specific abdominal pain.

Case 1: Laboratory test results upon admission were as follows: White blood cell count: 12.14 × 109/L (3.5-9.5 × 109/L); Hematocrit: 43% (40%-50%); C-reactive protein: 24 mg/L (0-8 mg/L); Serum amylase: 98 U/L (25-125 U/L); Serum lipase: 158 U/L (20-180 U/L); Serum calcium: 1.98 mmol/L (2.25-2.75 mmol/L); Alanine aminotransferase: 212 U/L (0-40 U/L); Aspartate aminotransferase: 54 U/L (0-40 U/L); Blood glucose level: 1.7 mmol/L (3.9-5.6 mmol/L).

Case 2: Blood test results were as follows: White blood cell count: 9.14 × 109/L (3.5-9.5 × 109/L); Hematocrit: 48% (40%-50%); C-reactive protein: 8 mg/L (0-8 mg/L); Serum amylase: 145 U/L (25-125 U/L); Serum lipase: 225 U/L (20-180 U/L); Blood glucose level: 6.7 mmol/L (3.9-5.6 mmol/L).

Case 3: No abnormal laboratory findings were noted.

Case 4: Pathological blood test was as follows: White blood cell count: 16.14 × 109/L (3.5-9.5 × 109/L); C-reactive protein: 48 mg/L (0-8 mg/L); Serum amylase: 171 U/L (25-125 U/L).

Case 1: CT scan showed 3 cm tumor nodule located within the neck of the pancreas.

Case 2: ERCP revealed pancreas divisum and mild chronic pancreatitis and obstruction of intrapancreatic common bile duct.

Case 3: CT showed a 4 cm neuroendocrine tumor located in the pancreatic tail.

Case 4: The neuroendocrine tumor was confirmed via selective angiography of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) and it was located in the pancreatic tail.

The diagnosis of pancreatic neck insulinoma was established.

Common bile duct obstruction and pancreas divisum were initial diagnosis.

The patient was diagnosed with pancreatic tail insulinoma.

Findings suggested the neuroendocrine tumor located in the pancreatic tail.

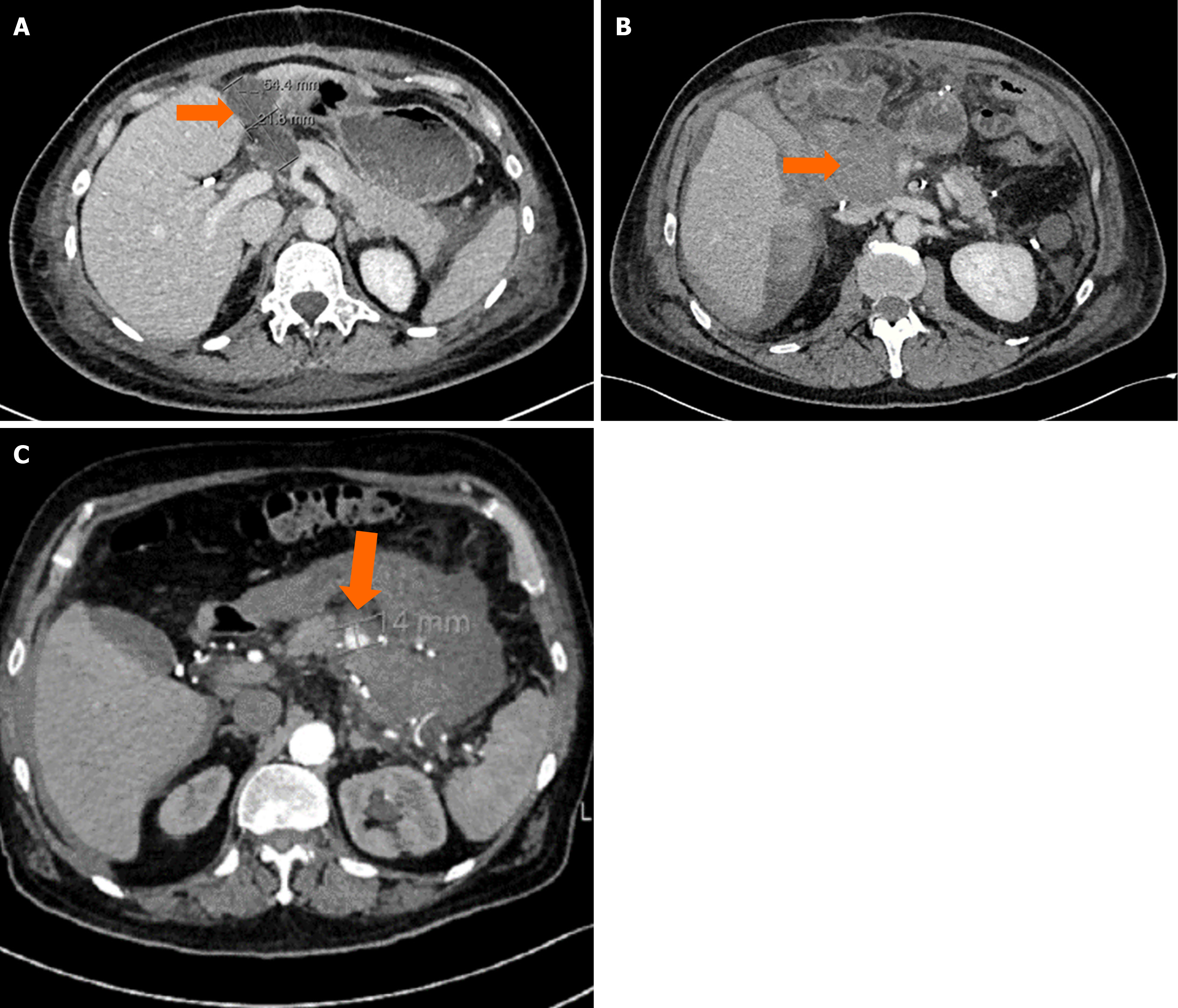

The patient underwent pancreatic tumor enucleation via open approach. No intraoperative difficulties were encountered. Macroscopically free tumor margins were achieved. The surgical procedure was uneventful. On postoperative day (POD) 7, the patient became febrile, so a CT was done, which showed a fluid collection at the resection site, indicating a possible pancreatic fistula (Figure 1A). Drainage of the collection under CT guidance was performed. Analysis of the drained fluid revealed an elevated concentration of alpha-amylase (56180 U/L), thus confirming the presence of a pancreatic fistula. Five days later, the patient became hypotensive and febrile, prompting a new CT scan. The previously described fluid collection had expanded, exhibiting features suggestive of hematoma, thereby raising concerns about a potential hemorrhage originating from the GDA.

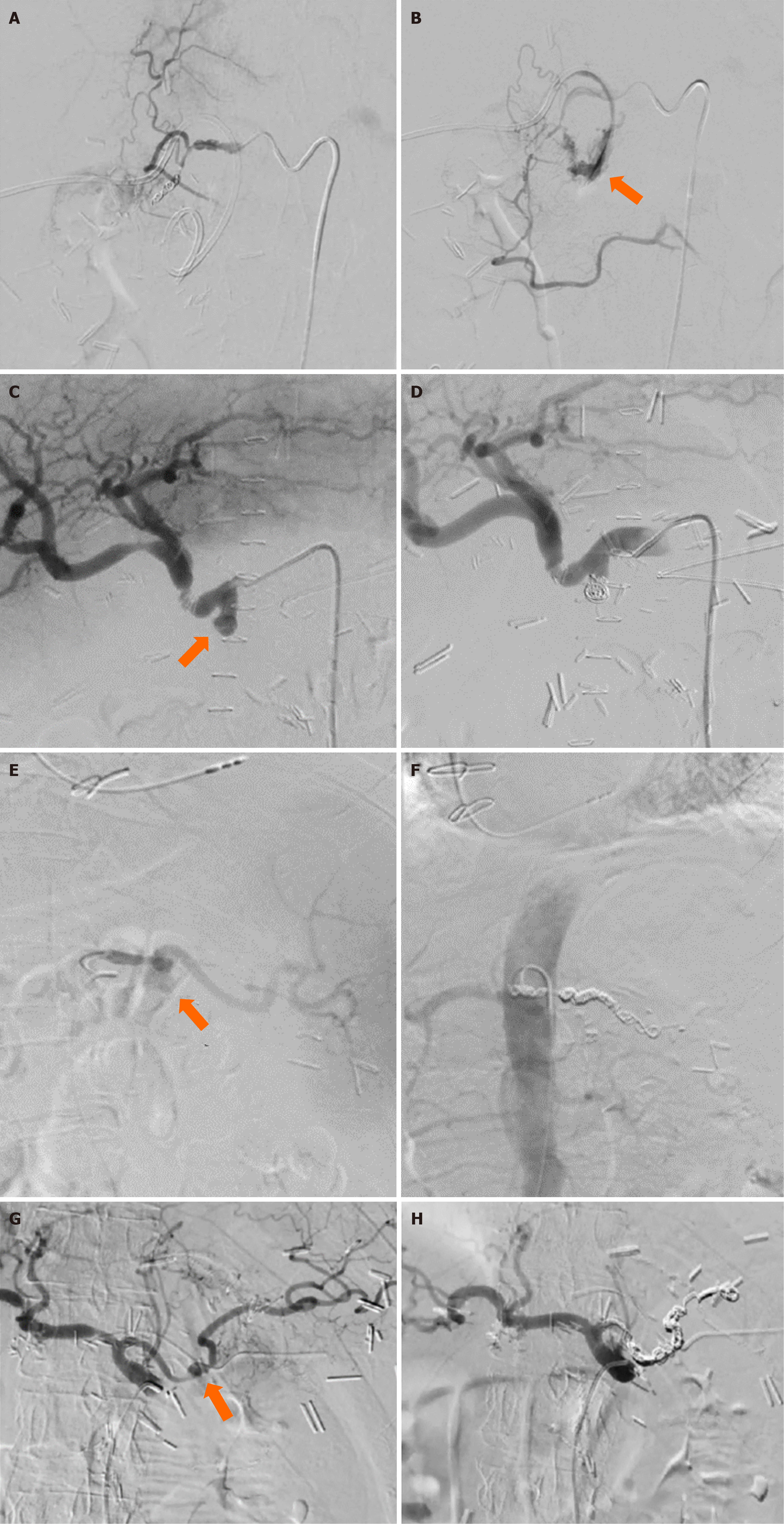

To address this concern, DSA was conducted, followed by embolization of the GDA with endovascular coils using the “front-back door” method (Figure 2A and B). The procedure was uneventful. Despite clinical and laboratory signs of adequate hemostasis, the patient had signs of progressive sepsis, so 12 hours after the radiological intervention, a rela

The patient underwent cephalic pancreatoduodenectomy with pancreatico-jejunal anastomosis. During the first post-operative week, the patient was recovering well. He was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and his abdominal drain was removed. On the POD 8, the patient complained of severe abdominal pain. CT identified a large collection of dense fluid at the resection site, as well as pneumoperitoneum (Figure 1B). Additionally, bilateral pleural effusion was noted, leading to minor respiratory distress.

Upon relaparotomy, a large amount of inflamed hematoma and fresh blood were found in the right abdominal and pelvic area. Hematoma was evacuated, peritoneal lavage was performed, and 4 abdominal drainage tubes were placed to drain subhepatic space, omental bursa and pelvis. The patient’s post-operative course was further complicated by the development of a grade B POPF. Conservative treatment of the fistula was initiated and the patient was discharged on POD 11 in good condition, with the one remaining drain left as there was persistent moderate fistula output. Five days later, the patient returned to the emergency room due to sudden bloody secretion from the abdominal drainage tube. An urgent abdominal CT was performed, revealing a potential PSAN of the GDA stump. The PSAN was confirmed via DSA, followed by successful endovascular coil embolization of the GDA stump (Figure 2C and D).

Surgery was indicated and it included spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy and cholecystectomy. The procedure and postoperative recovery were uneventful and the patient was discharged on the POD 16. Two months later, on the POD 57, the patient was readmitted to the emergency department due to episodes of hematemesis occurring 3 to 4 times within the previous 24 hours and accompanied by upper abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed a soft abdomen with lower quadrant tenderness on palpation. Emergency CT identified two heterogeneous masses, one of which was connected to the splenic artery (SA), thus confirming the diagnosis of a PSAN of the SA (Figure 1C).

The patient underwent endovascular embolization of the splenic PSAN with 11 coils, which successfully managed the bleeding (Figure 2E and F). The second heterogeneous mass, a hematoma, was drained using the Seldinger technique. The splenic abscess and pleural effusions were treated conservatively.

The patient underwent standard cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy. On the POD 2, the patient became febrile. An emergent abdominal CT revealed two fluid collections, which were then drained percutaneously, and the drained content was sent for microbiological analysis. The patient’s antibiotic therapy was corrected, which led to a reduction in inflammatory markers. On the POD 29 the patient was discharged in good condition. After 14 days, on POD 43, the patient presented to the emergency department with hematemesis. She was also persistently hypoglycemic. An abdominal CT scan with contrast revealed new areas of extravasation during the arterial phase, confirming the presence of a PSAN of the SA. The patient underwent endovascular embolization of the SA-PSAN, which included the application of 10 coils (Figure 2G and H). After the procedure, the patient’s blood glucose levels were normalized.

No additional complications were seen, and the patient was discharged on POD 18. The two remaining abdominal drains were removed two months later. At one-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic and showed no evidence of pancreatic insufficiency.

Subsequently, the abdominal drain was safely removed after 2 weeks, and the patient was discharged 3 days later. At 2-years follow-up no complaints were reported by the patient.

The patient was discharged on the 24th day after admission in stable general condition. At 1-year follow up the patient was asymptomatic.

The patient was discharged 14 days later, euglycemic, and with the recommendation of meticulous follow-up with an endocrinologist, due to reduced perfusion of the remaining pancreatic tissue following SA embolization. At 1-year follow-up the patient was good and no signs of glycemic disorders were found.

Delayed gastric emptying, pancreaticojejunal anastomotic failure, and intra-abdominal abscess are predominant causes of morbidity after pancreatectomies. PPH is reported less frequently, but it has significantly higher mortality rates (a mortality rate between 30 and 50%) as compared to other complications, with the principal cause of death being over

Unlike in E-PPH, in D-PPH, the treatment decision making process is often challenging. and the treatment remains controversial since there is no uniformly accepted algorithm. Historically, urgent surgical exploration was the only justified intervention, but the development of endovascular methods changed the paradigm in the treatment of D-PPH since it caused a shift toward the use of angiography with embolization[4,5,9,10]. Angiography may easily localize the bleeding site, and embolization can be immediately performed. Therefore, when newly formed visceral PSAN are the source of bleeding, which, according to 2008 meta-analysis[11], happens in approximately one third of PPH cases, endovascular embolization should be considered as the first line of treatment[11,12].

Endovascular approach is even more justified as time after surgery passes since it has been shown that over time the probability of anastomotic bleeding decreases and that of visceral arterial bleeding increases. Main advantages of the endovascular approach is minimal invasiveness and the fact that it avoids damage to other organs. In addition, surgical procedure is associated with high risk of complications and often it ends with completion pancreatectomy. Modified anatomy, postoperative adhesions, and inflammatory peripancreatic changes compromise the safety of the surgical approach[13]. Therefore, in D-PPH when there is no massive bleeding associated with hemodynamic instability, every effort should be made to avoid surgery. Angiography may be both diagnostic and therapeutic, and even if there is no complete success, it may delay the need for urgent surgery.

Given the danger of PPH, many authors investigated possible intraoperative or postoperative strategies for the pre

Study from Floortje van Oosten et al[15] showed that the mortality rate was lower after a primary endovascular app

In 2016, international study group of pancreatic surgery published a revised classification and grading system for POPF. The new term proposed for what was formerly grade A POPF is biochemical leak, and it is no longer considered a true pancreatic fistula or an actual surgical complication[16]. A biochemical leak, by definition, has no clinical impact. It implies no deviation from the normal postoperative pathway and does not result in a prolonged hospital stay. Grade B and C POPF remain clinically relevant, defined as a drain output of any measurable volume of fluid with an amylase level greater than three times the upper institutional normal serum amylase level, and associated with a clinically relevant development/condition related directly to the POPF. Grade B refers to a properly defined fistula that always changes the usual postoperative course. Once single or multiple organ dysfunction occurs, or the patient needs reope

The most commonly reported origin of PPH is the stump of the GDA. However, as reported by Ielpo et al[17], the artery involved is usually related to a specific pathology. For example, splenic PSANs are most commonly associated with pancreatitis and extended pancreatic resection, while hepatic artery PSAN is usually iatrogenic after liver resection or transplantation[18]. Lee et al[19] report PSAN of the GDA, common hepatic artery, proper hepatic artery, and the left hepatic artery as the most commonly occurring locations after pancreatoduodenectomy. In our case series, we encountered two PSAN of the GDA stump, and two SA-PSAN, one of which occurred alongside a left hepatic artery PSAN. All of these complications presented after pancreatic resection.

Patients we present in this case series developed POPFs during the early days of recovery. The presence of pancreatic fistulas was suspected due to increased postoperative drain output, and confirmed via laboratory analysis of the drained fluid, which revealed a more than 3 times greater value of alpha-amylase than the normal serum concentration. All of the patients experienced late grade B PPH. The onset of bleeding ranged from POD 7 to POD 57. Massive arterial bleeding can occur late in the postoperative period. Lee et al[19] reported a median period of 21 days for pseudoaneurysmal blee

Depending on the location of the PSAN, the subsequent hemorrhage will present either as extraluminal or intra

PPH is relatively uncommon, but it is a leading cause of surgical mortality after pancreatic surgery. Careful monitoring and meticulous follow-up are required for all patients post-operatively, especially in the case of confirmed POPF, which is the most significant risk factor for the development of a PPH. Angiography as a diagnostic and therapeutic method may be an optimal first-line treatment for the management of delayed PPHs. In our experience, endovascular treatment for hemorrhagic complications of pancreatic resections has shown satisfactory results.

| 1. | Malleo G, Vollmer CM Jr. Postpancreatectomy Complications and Management. Surg Clin North Am. 2016;96:1313-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Yeo CJ, Büchler MW. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 1945] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dardik H. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:508-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roulin D, Cerantola Y, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Systematic review of delayed postoperative hemorrhage after pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Darnis B, Lebeau R, Chopin-Laly X, Adham M. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): predictors and management from a prospective database. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:441-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ansari D, Tingstedt B, Lindell G, Keussen I, Ansari D, Andersson R. Hemorrhage after Major Pancreatic Resection: Incidence, Risk Factors, Management, and Outcome. Scand J Surg. 2017;106:47-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rumstadt B, Schwab M, Korth P, Samman M, Trede M. Hemorrhage after pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;227:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nagai M, Sho M, Akahori T, Nishiwada S, Nakagawa K, Nakamura K, Tanaka T, Nishiofuku H, Kichikawa K, Ikeda N. Risk Factors for Late-Onset Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage After Pancreatoduodenectomy for Pancreatic Cancer. World J Surg. 2019;43:626-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhou TY, Sun JH, Zhang YL, Zhou GH, Nie CH, Zhu TY, Chen SQ, Wang BQ, Wang WL, Zheng SS. Post-pancreaticoduodenectomy hemorrhage: DSA diagnosis and endovascular treatment. Oncotarget. 2017;8:73684-73692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Blanc T, Cortes A, Goere D, Sibert A, Pessaux P, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A. Hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: when is surgery still indicated? Am J Surg. 2007;194:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Limongelli P, Khorsandi SE, Pai M, Jackson JE, Tait P, Tierris J, Habib NA, Williamson RC, Jiao LR. Management of delayed postoperative hemorrhage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1001-7; discussion 1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khalsa BS, Imagawa DK, Chen JI, Dermirjian AN, Yim DB, Findeiss LK. Evolution in the Treatment of Delayed Postpancreatectomy Hemorrhage: Surgery to Interventional Radiology. Pancreas. 2015;44:953-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yekebas EF, Wolfram L, Cataldegirmen G, Habermann CR, Bogoevski D, Koenig AM, Kaifi J, Schurr PG, Bubenheim M, Nolte-Ernsting C, Adam G, Izbicki JR. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: diagnosis and treatment: an analysis in 1669 consecutive pancreatic resections. Ann Surg. 2007;246:269-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Montorsi RM, Zonderhuis BM, Daams F, Busch OR, Kazemier G, Marchegiani G, Malleo G, Salvia R, Besselink MG. Treatment strategies to prevent or mitigate the outcome of post-pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): a review of randomized trials. Int J Surg. 2023;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Floortje van Oosten A, Smits FJ, van den Heuvel DAF, van Santvoort HC, Molenaar IQ. Diagnosis and management of postpancreatectomy hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:953-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bassi C, Marchegiani G, Dervenis C, Sarr M, Abu Hilal M, Adham M, Allen P, Andersson R, Asbun HJ, Besselink MG, Conlon K, Del Chiaro M, Falconi M, Fernandez-Cruz L, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Fingerhut A, Friess H, Gouma DJ, Hackert T, Izbicki J, Lillemoe KD, Neoptolemos JP, Olah A, Schulick R, Shrikhande SV, Takada T, Takaori K, Traverso W, Vollmer CM, Wolfgang CL, Yeo CJ, Salvia R, Buchler M; International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 Years After. Surgery. 2017;161:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3041] [Cited by in RCA: 2957] [Article Influence: 369.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 17. | Ielpo B, Caruso R, Prestera A, De Luca GM, Duran H, Diaz E, Fabra I, Olivares S, Quijano Y, Vicente E. Arterial pseudoaneurysms following hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery: a single center experience. JOP. 2015;16:85-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ding X, Zhu J, Zhu M, Li C, Jian W, Jiang J, Wang Z, Hu S, Jiang X. Therapeutic management of hemorrhage from visceral artery pseudoaneurysms after pancreatic surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1417-1425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee JH, Hwang DW, Lee SY, Hwang JW, Song DK, Gwon DI, Shin JH, Ko GY, Park KM, Lee YJ. Clinical features and management of pseudoaneurysmal bleeding after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am Surg. 2012;78:309-317. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Brodie B, Kocher HM. Systematic review of the incidence, presentation and management of gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm after pancreatic resection. BJS Open. 2019;3:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iswanto S, Nussbaum ML. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm after surgical treatment for pancreatic cancer: minimally invasive angiographic techniques as the preferred treatment. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:287-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |