Published online Oct 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i29.6327

Revised: July 4, 2024

Accepted: July 23, 2024

Published online: October 16, 2024

Processing time: 89 Days and 18.9 Hours

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder involving the gut–brain interaction that is characterized by recurring episodes of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and interspersed complete normal periods. Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome (SMAS) is a vascular condition in which the horizontal portion of the duodenum is compressed due to a reduced angle between the aorta and the SMA. This condition presents with symptoms similar to CVS, posing challenges in distinguishing between the two and often resulting in misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment.

A 20-year-old female patient presented with recurrent episodes of vomiting and experienced a persistent fear of vomiting for the past 2 years. She adopted cons

We present a rare case of CVS in an adult complicated with SMAS and propose additional treatment with nutritional support, pharmacological intervention, and psychotherapy.

Core Tip: Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a rare gastrointestinal disorder characterized by intense, recurrent vomiting episodes. Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome (SMAS) occurs when the third part of the duodenum is compressed by the SMA, often leading to vomiting similar to CVS. Weight loss resulting from CVS can contribute to the development of SMAS, and conversely, SMAS can mimic CVS symptoms. To distinguish between these conditions, detailed clinical examination is essential, particularly with abdominal imaging. Additionally, long-term closely follow-up is necessary to differentiate between the two. Comprehensive interventions involving psychosomatic treatment are necessary to address these conditions.

- Citation: Liu B, Sun H, Liu Y, Yuan ML, Zhu HR, Zhang W. Comprehensive interventions for adult cyclic vomiting syndrome complicated by superior mesenteric artery syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(29): 6327-6334

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i29/6327.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i29.6327

Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS) is a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) involving the intricate con

A 20-year-old female undergraduate student presented with recurrent vomiting and persistent fear over 2 years.

The patient had been enduring recurring bouts of severe vomiting over 2 years, coupled with a persistent fear of its return. After the onset, she consistently experienced severe vomiting, which did not respond to conventional antiemetic medication, except for a high dose of sedative to induce sleep. She underwent multiple examinations, including upper gastrointestinal series, upper endoscopy, and enhanced abdominal CT. Due to the absence of identified organic abnor

Her past medical history has been good with no significant underlying illnesses.

Since childhood, she has had a mild, obedient and endearing personality, maintaining good relations with her family. She has a younger brother with whom she shares a good relationship. She excelled academically; however, her performance in the college entrance examination fell short of her aspirations, leading her to cry out in frustration. Furthermore, she has experienced betrayal from an ex-boyfriend. Her parents run their own businesses, resulting in a well-off financial status at home. After the patient fell ill, her mother lost interest in work, dedicating a significant amount of time to provide meticulous care for her daughter. She accompanied the patient everywhere, seeking medical advice and treatment, researching relevant information online, and maintaining extremely detailed records of the patient's medical history.

She appeared thin and weak, with a PICC line inserted in her left arm. Her vital signs were within normal limits, and there were no apparent abnormalities noted upon examination of her lungs and heart. Her abdomen was flat and soft, showing no signs of significant tenderness upon palpation or rebound tenderness. Additionally, there were no positive findings detected during the examination of her neurological system.

She appeared conscious and friendly, communicating effectively. She shared concerns about experiencing vomiting episodes again and showed hesitancy towards eating, along with anxiety regarding her prognostic outlook. She felt low in mood, yet did not mention feelings of extreme negativity, despair, or suicidal thoughts. There were no apparent signs of psychotic symptoms. Her thinking abilities seemed unaffected, and she showed the ability to manage daily tasks on her own.

All blood test results were within normal limits.

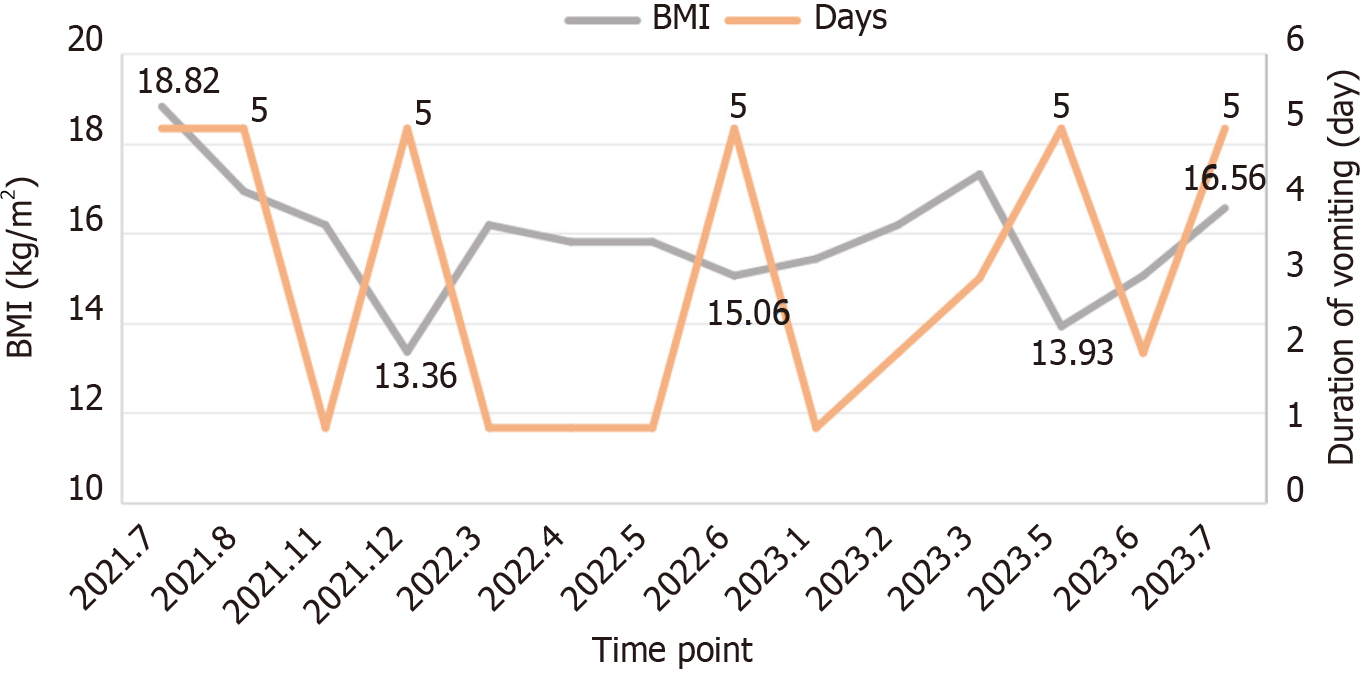

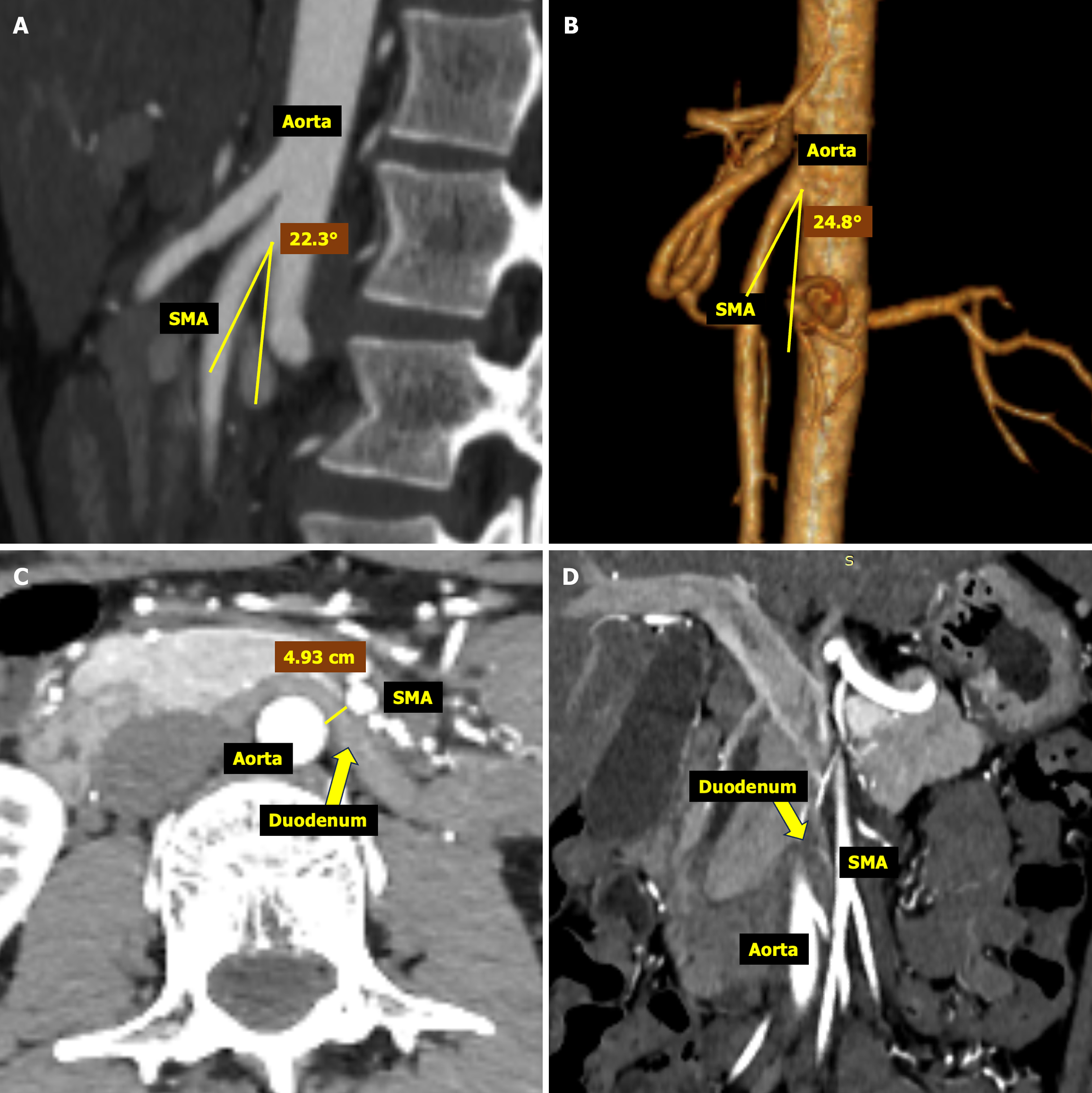

Abdominal ultrasound examination revealed no obvious abnormalities. Follow-up CTA revealed improvement in the angle between the aorta and SMA to 24.8°, indicating a favorable treatment response. However, cross-sectional imaging showed that the distance between the horizontal plane of the aorta and SMA at the level of the duodenum remained < 5 mm, suggesting ongoing potential for SMA compression of the duodenum (Figure 2). Electroencephalography and brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed no abnormalities.

Combined with the patient’s medical history, we arrived at the comorbid diagnoses of CVS (Rome IV), SMAS (ICD-10), and anxiety disorder (ICD-10).

During hospitalization, the patient experienced severe and unrelenting vomiting, showing no response to typical antiemetics such as triptans and ondansetron. She displayed a fear or heightened sensitivity to both sound and light during the episode. Her vomiting subsided only after receiving high doses of sedatives (such as benzodiazepines) until she fell asleep. She continued to receive ongoing parenteral nutrition through a PICC and gradually transitioned to a more liquid-based diet (Table 1). In addition, she received pancreatin enteric-coated capsules (2 capsules tid) and Bacillus coagulans dual probiotic enteric-coated capsules (2 capsules tid) for regulating GI function. As for her anxiety aspect, her drug doses were titrated to reach the final prescribed doses of duloxetine (60 mg/d), olanzapine (10 mg/d), depakine (500 mg/d), and clonazepam (0.5 mg/d). She also underwent mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) following the acute episode.

| Formula | Specifications | Dosage (mL) | Frequency |

| Compound amino acid injection | 250 mL: 28.5 g | 500 | Ivgtt qd |

| Compound amino acid injection | 8.5%/250 mL | 250 | |

| Glucose injection | 10%/100 mL | 250 | |

| Glucose injection | 5%/500 mL | 300 | |

| Medium- and long-chain fat emulsion for injection | 20%: 250 mL | 250 | |

| Concentrated sodium chloride injection | 10 mL: 1 g | 30 | |

| Multiple microelement injection | 10 mL | 10 | |

| Sodium glycerophosphate injection | 10 mL: 2.16 g | 10 | |

| Magnesium sulfate injection | 10 mL: 2.5 g | 10 | |

| Calcium gluconate injection | 10 mL: 1 g | 5 | |

| Water-soluble vitamin injection | 1 vial | 1 vial | |

| Fat-soluble vitamin injection | 10 mL | 10 |

After 17 days in hospital, the patient was released when achieving clinical recovery. For the initial 2 weeks after discharge, she progressed well. However, she experienced a relapse following a bout of dysmenorrhea, showing similar but relatively mild symptoms as before. After receiving nutrient supplementation in local hospital, she recovered again. Fortunately, she did not exhibit excessive fear regarding her treatment and health.

To the best of our knowledge, we have not found any similar reports of comorbidity between CVS and SMAS in adults. Recently, Berken et al[6] documented a case of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS), with a symptom pattern resembling CVS, complicated by SMAS, indicating that SMAS occurs following precipitous weight loss resulting from CHS. While CHS is currently considered a limited subset of CVS[1], it cannot explain the origin and development of other forms of CVS. Another case involved an adolescent diagnosed with both SMAS and CVS, where SMAS was identified as the cause of CVS, as CVS symptoms improved after treating SMAS[7]. However, in our case, SMAS appeared to result from the weight loss caused by CVS, as CVS symptoms did not improve even after alleviating SMAS. It has been reported that CVS often coexists with other conditions, including migraine headaches, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, anxiety, depression, panic disorder, and seizures[8]. In the present case, the patient also exhibited severe anxiety disorder. It is widely accepted that excessive anxiety seems to be an independent predisposing factor to CVS[9]. While CVS is more common in children, its recognition is increasingly expanding among adults[8,10]. Because the etiology and pathogenesis of CVS is elusive, its diagnosis is based on the Rome IV symptom-based criteria[1,8], depending on carefully observing the symptoms and ensuring that there are no underlying physiological causes that could account for them. The characteristic vomiting episodes with distinct intervals of no vomiting form the fundamental pattern of CVS, often accompanied by additional symptoms such as abdominal pain, thirst, migraine headaches, sensi

| Characteristics | CVS | SMAS |

| Onset | Sudden and recurrent episodes | Gradual onset |

| Symptoms | Severe nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain | Early satiety, postprandial abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting |

| Triggers | Stress, infections, certain foods, menses, etc. | Physical activity, weight loss, position changes, dietary changes |

| Duration of episodes | Lasts for hours to days, with variable duration of symptom-free intervals | Persistent until compression is resolved |

| Age of onset | More common in children, but can occur in adults | Typically in adolescents and young adults |

| Diagnostic tests | Mainly clinical diagnosis, exclusion of other causes | Upper gastrointestinal series, endoscopy, CT scan |

| Treatment | Anti-emetics, anti-anxiety medications, lifestyle changes, psychotherapy | Nutritional support, small frequent meals, surgery for decompression |

Nausea and vomiting are shared symptoms in CVS and SMAS, often leading to confusion, particularly in patients with low weight. Early recognition, diagnosis and management of CVS in clinical practice pose considerable challenges. It is imperative to concurrently address both the underlying primary condition and any secondary conditions effectively. Because the pathophysiology of CVS remains unclear, it is essential to adopt comprehensive strategies encompassing a bio-psychosocial perspective. To gain a better understanding of the patient's outcome, a more thorough and prolonged follow-up is essential.

We appreciate the patient and her mother's cooperation, as well as the assistance from multiple departments including radiology, nutrition, gastroenterology and psychiatry.

| 1. | Frazier R, Li BUK, Venkatesan T. Diagnosis and Management of Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome: A Critical Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:1157-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kumar N, Bashar Q, Reddy N, Sengupta J, Ananthakrishnan A, Schroeder A, Hogan WJ, Venkatesan T. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome (CVS): is there a difference based on onset of symptoms--pediatric versus adult? BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, Malagelada JR, Suzuki H, Tack J, Talley NJ. Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 818] [Cited by in RCA: 975] [Article Influence: 108.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Welsch T, Büchler MW, Kienle P. Recalling superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Dig Surg. 2007;24:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oka A, Awoniyi M, Hasegawa N, Yoshida Y, Tobita H, Ishimura N, Ishihara S. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: Diagnosis and management. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11:3369-3384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 6. | Berken JA, Saul S, Osgood PT. Case Report: Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome in an Adolescent With Cannabinoid Hyperemesis. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:830280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dimopoulou A, Zavras N, Alexopoulou E, Fessatou S, Dimopoulou D, Attilakos A. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome mimicking cyclic vomiting syndrome in a healthy 12-year-old boy. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:168-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Venkatesan T, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Jaradeh SS, Hasler WL, Issenman RM, Adams KA, Sarosiek I, Stave CD, Sharaf RN, Sultan S, Li BUK. Guidelines on management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults by the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome in 41 adults: the illness, the patients, and problems of management. BMC Med. 2005;3:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, Bousvaros A, Chong SK, Fleisher DR, Hasler WL, Hyman PE, Issenman RM, Li BU, Linder SL, Mayer EA, McCallum RW, Olden K, Parkman HP, Rudolph CD, Taché Y, Tarbell S, Vakil N. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:269-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ford AC, Mahadeva S, Carbone MF, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet. 2020;396:1689-1702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 57.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li BUK. Managing cyclic vomiting syndrome in children: beyond the guidelines. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177:1435-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sharaf RN, Venkatesan T, Shah R, Levinthal DJ, Tarbell SE, Jaradeh SS, Hasler WL, Issenman RM, Adams KA, Sarosiek I, Stave CD, Li BUK, Sultan S. Management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults: Evidence review. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31 Suppl 2:e13605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lewis SR, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Alderson P, Smith AF. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition and enteral versus a combination of enteral and parenteral nutrition for adults in the intensive care unit. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD012276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Reed-Knight B, Claar RL, Schurman JV, van Tilburg MA. Implementing psychological therapies for functional GI disorders in children and adults. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Slutsker B, Konichezky A, Gothelf D. Breaking the cycle: cognitive behavioral therapy and biofeedback training in a case of cyclic vomiting syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2010;15:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim YW, Lee SH, Choi TK, Suh SY, Kim B, Kim CM, Cho SJ, Kim MJ, Yook K, Ryu M, Song SK, Yook KH. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as an adjuvant to pharmacotherapy in patients with panic disorder or generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:601-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lippl F, Hannig C, Weiss W, Allescher HD, Classen M, Kurjak M. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist's view. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:640-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pottorf BJ, Husain FA, Hollis HW Jr, Lin E. Laparoscopic management of duodenal obstruction resulting from superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1319-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Kurisu K, Yamanaka Y, Yamazaki T, Yoneda R, Otani M, Takimoto Y, Yoshiuchi K. A clinical course of a patient with anorexia nervosa receiving surgery for superior mesenteric artery syndrome. J Eat Disord. 2021;9:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Arthurs OJ, Mehta U, Set PA. Nutcracker and SMA syndromes: What is the normal SMA angle in children? Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e854-e861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yang WL, Zhang XC. Assessment of duodenal circular drainage in treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:303-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |