Published online Oct 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i28.6217

Revised: June 20, 2024

Accepted: July 19, 2024

Published online: October 6, 2024

Processing time: 190 Days and 14.6 Hours

Glaucoma is caused by increased intraocular pressure (IOP) that damages the optic nerve, leading to blindness. The Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV) is a glau

Here, we have reported a case of a 55-year-old female who developed both hyphema and pigmentation as a result of AGV implantation. We confirmed UGH syndrome secondary to AGV implantation after the patient underwent another surgery to shorten and reposition the AGV tube. After the second surgery, the patient’s IOP was reduced, and she had a clear cornea and no signs of hyphema.

This first report of UGH syndrome as a complication of AGV implantation reminds clinicians that frequent follow-up is paramount.

Core Tip: Glaucoma is caused by increased intraocular pressure that damages the optic nerve leading to blindness. Intraocular pressure can be relieved by implanting a drainage device. We report here a case of a 55-year-old female who developed uveitis glaucoma hyphema (UGH) syndrome as a complication after drainage implantation surgery. After treatment with a second surgery to shorten the drainage tube, the patient recovered well with a decrease in intraocular pressure and clearing of the hyphema. This represents the first report of UGH syndrome occurring after the implantation of a drainage device to treat glaucoma.

- Citation: Altwijri RJ, Alsirhy E. Uveitis glaucoma hyphema syndrome as a result of glaucoma implant: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(28): 6217-6221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i28/6217.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i28.6217

Glaucoma is a chronic optic neuropathy caused by increased intraocular pressure (IOP) that damages the optic nerve and is one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide. Reducing IOP is the most effective treatment for glaucoma currently[1,2]. The Ahmed glaucoma valve (AGV) is a particularly effective interocular therapeutic device that can be implanted in glaucoma patients with uncontrolled IOP, even in those who showed resistance to medication-based intervention[3,4]. The AGV consists of three parts: A plate; a drainage tube; and a valve mechanism. Although AGV implantation is one of the most effective treatments for reducing IOP, it is possible that patients can develop postoperative complications such as hyphema[5].

Uveitis glaucoma hyphema (UGH) syndrome is a rare condition that occurs as a complication of intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, mainly when there is contact between the IOL and the iris or ciliary body. The blood-aqueous barrier breakdown due to mechanical trauma releases blood cells and proteins into the anterior chamber. The combination of iris pigment, blood cells, and proteins further contributes to the blockage of the trabecular meshwork, exacerbating the rise in IOP. The elevated IOP can ultimately lead to glaucoma, and the presence of blood in the anterior chamber adds another layer of complications[6,7]. UGH syndrome typically develops in days but can also develop much slower, over a period of years. Postoperative complications of IOL implants can last for weeks to months, prompting the patient to return for further assessment and management[8,9].

Management of UGH syndrome typically involves addressing the underlying issue, which might require surgical intervention, and managing other complications associated with the initial implantation operation[10]. Although UGH syndrome is known to develop following IOL implantation[6,7], it has not yet been reported following AGV imp

Herein, we report a case of a female who developed UGH syndrome after AGV implantation. To our knowledge, no previous reports of UGH syndrome development after AGV implantation exist. This report detailed the diagnostic work-up to this unusual condition, the surgical management plan, its outcomes, and its caveats.

A 55-year-old female presented to our department at King Abdulaziz University Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia as a follow up visit after AGV implantation surgery.

One day prior to presentation, the patient had received an AGV implant in the left eye. She reported that she was administering topical anti-glaucoma medications in both eyes.

The patient had experienced left-sided monocular vision for many years. She also had been diagnosed with bilateral advanced open-angle glaucoma many years prior to presentation. When her left IOP was at 36 mmHg, she had undergone treatment with deep sclerectomy and phacoemulsification with IOL and later with Yag laser goniopuncture. The IOP for the left eye was lowered to 16 mmHg. The cup disc ratio had been recorded as 1.00 in the right eye and 0.85 in the left eye. There was no light perception in the right eye, and the visual acuity of the left eye was 20.0/28.5.

Because the IOP in the left eye was not ideal for the disc status and medication was not controlling the IOP, AGV implantation was recommended and performed 1 month later via the standard surgical procedure. The tube was inserted in the anterior chamber with adequate length. The bevel was forward-facing, and the tube was covered under the conjunctiva with pericardial tissue (Tutoplast®; Coloplast Corporation, Minneapolis, MN, United States). No complications had occurred during the surgery.

Personal and family history-taking provided no other relevant information for the current case.

On day 1 post-operation, the patient’s left eye IOP was 12 mmHg.

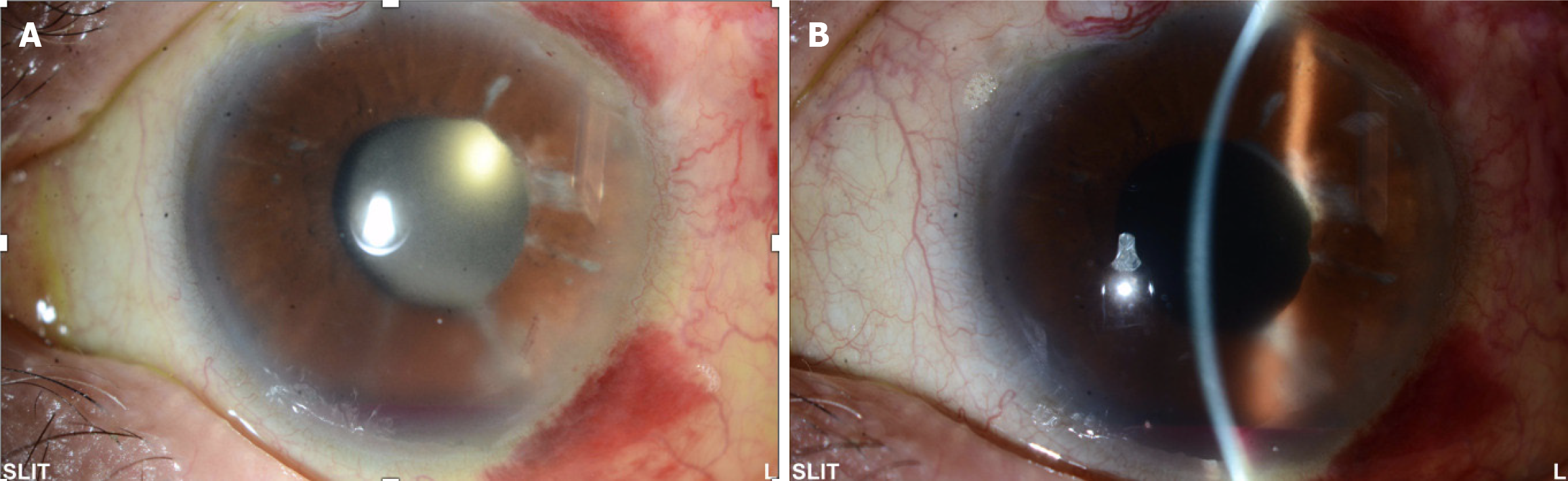

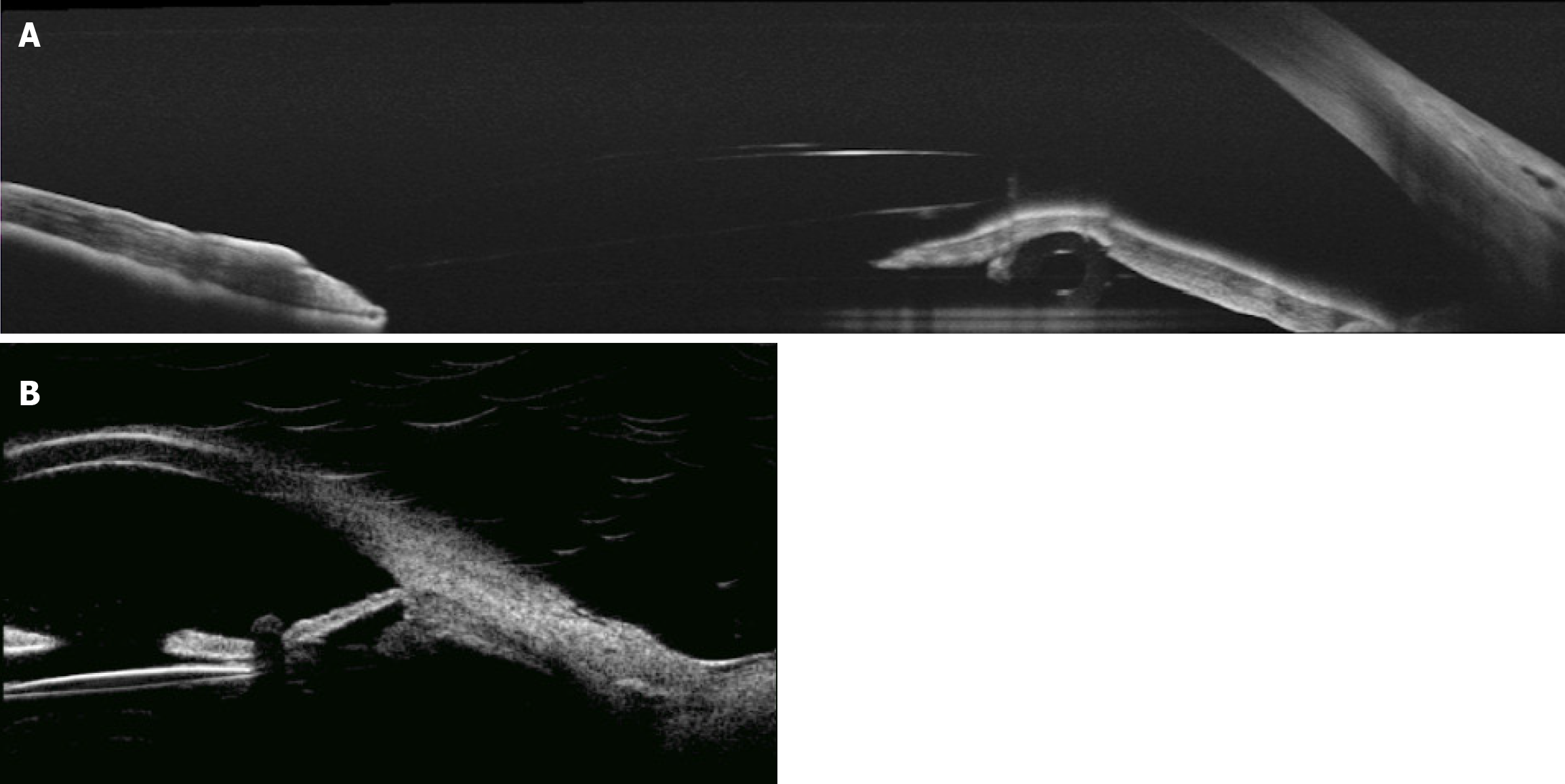

Ultrasound biomicroscopy (commonly referred to as UBM) and slit-lamp biomicroscopy showed the cornea to be clear. The implanted AGV tube was observed to be facing away from the corneal endothelium but extending and resting on the iris, indenting it backwards, with the tube and plate being well covered under conjunctival tissue. The patient was discharged with instructions to apply a topical methylprednisolone 4 times a day (Pred Forte®; Allergan, Irvine, CA, United States) on a tapering regimen and ofloxacin 4 times a day. However, at week 1 post-operation, she developed inferior hyphema (about 2 mm level) and heavy iris pigmentation was observed with inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber (Figure 1). At that time, we increased the frequency of Pred Forte® to once every 2 hours, with instructions to re-attend follow-up 2 weeks later. When she came back, the hyphema was resolved but imaging showed the heavy pigmentation and infiltrating inflammatory cells were still abundant in the anterior chamber.

The development of hyphema and heavy pigmentation led us to consider differential diagnoses. The patient may have been experiencing UGH syndrome or iatrogenic pigment dispersion glaucoma secondary to glaucoma implant. We hypothesized that the tube pressing on the anterior layer of the iris, causing it to be sandwiched between the tube and the IOL, was resulting in the posterior iris rubbing against the IOL (Figure 2).

Surgery was ordered for the following day to reposition and shorten the tube in the anterior chamber. During the procedure, the tube was explored from the conjunctival side. It was removed, shortened, and reinserted in a position that was more anterior in order to avoid rubbing the iris. We also ensured that the tube was positioned away from the cornea. The surgery concluded uneventfully.

On day 1 after the repositioning surgery all inflammatory cells and the aberrant pigmentation disappeared completely, indicating ultimate success of the intervention and supporting the diagnosis of UGH syndrome due to the placement of the tube.

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of blindness and treatment is necessary to stop irreparable damage to the optic nerve caused by increased IOP as the disease progresses. Currently, the most effective treatment for glaucoma is reduction of IOP[1,2] by medications or by surgery if needed. AGV implantation can be used when patients experience chronic elevated IOP[3,4].

UGH syndrome is a known complication of cataract surgery that may occur as a result of implant malposition. Patients with UGH syndrome usually experience blurred vision that can continue for weeks after the operation and is associated with pain, photophobia, and redness[11]. Clinical symptoms associated with UGH syndrome include increased IOP, micro-hyphema or hyphema, cell infiltration into the anterior chamber, flare or hypopyon, inflammatory cell deposits over the IOL optic or haptic, and vitreous hemorrhage if the posterior capsule is not intact. Gonioscopy and UBM are useful for the diagnosis of UGH syndrome.

Various treatment options are available for UGH syndrome. Anti-glaucoma medications can reduce IOP. In addition, topical corticosteroids are effective in controlling inflammation and reducing IOP. Cycloplegics play a critical role in relieving ciliary spasms and inflammation. The definitive treatment for UGH syndrome may involve IOL exchange or repositioning[11].

UGH syndrome is often misdiagnosed as pigment dispersion syndrome (PDS). PDS is characterized by pigment dispersion into the anterior chamber, which ultimately clogs the trabecular meshwork and leads to increased IOP and secondary open-angle glaucoma[12,13]. PDS can result from intraocular surgery with inappropriate implantation[14,15], leading to iris chafing[16]. PDS symptoms include pigmentation over the posterior surface of the central cornea (Krukenberg spindle), pigmented cells in the anterior chamber, and iris transillumination defects mainly at the edge of the lens[17].

Gonioscopy is also the primary tool to diagnose PDS[18]. Examining the undilated pupil for transillumination defects and assessing the position of the IOL is crucial in accurately diagnosing UGH syndrome and PDS. Gonioscopy can assist in identifying issues such as hyphema or potential causes of bleeding, including neovascular glaucoma[19].

In our case, the hyphema may have been caused by trauma from the tube during the surgery or from inflammation the occurred after the implantation. We determined that the hyphema did not occur during the surgery itself in accordance with the 1-week period before the hyphema appearance. If there had been trauma during the surgery, the hyphema would have developed shortly (within 1 day) after surgery. The aberrant pigmentation observed in our patient resolved after shortening and repositioning the tube of the AGV, leading us to a diagnosis of UGH syndrome in our patient.

This first report of a case of UGH syndrome resulting from AGV implantation is distinct as UGH syndrome is typically associated with IOL implantation. The patient has agreed to frequent future follow ups so that we may monitor and track any further complications related to the repositioning surgery and unique circumstances of this patient. It is recom

| 1. | Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2081-2090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5390] [Cited by in RCA: 4475] [Article Influence: 406.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Riva I, Roberti G, Oddone F, Konstas AG, Quaranta L. Ahmed glaucoma valve implant: surgical technique and complications. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:357-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Riva I, Roberti G, Katsanos A, Oddone F, Quaranta L. A Review of the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve Implant and Comparison with Other Surgical Operations. Adv Ther. 2017;34:834-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Coleman AL, Hill R, Wilson MR, Choplin N, Kotas-Neumann R, Tam M, Bacharach J, Panek WC. Initial clinical experience with the Ahmed Glaucoma Valve implant. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhou MW, Wang W, Huang WB, Chen SD, Li XY, Gao XB, Zhang XL. Adjunctive with versus without intravitreal bevacizumab injection before Ahmed glaucoma valve implantation in the treatment of neovascular glaucoma. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:1412-1417. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Armonaite L, Behndig A. Seventy-one cases of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphaema syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:69-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Apple DJ, Mamalis N, Loftfield K, Googe JM, Novak LC, Kavka-Van Norman D, Brady SE, Olson RJ. Complications of intraocular lenses. A historical and histopathological review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;29:1-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramakrishnan MS, Wald KJ. Current Concepts of the Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphema (UGH) Syndrome. Curr Eye Res. 2023;48:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zemba M, Camburu G. Uveitis-Glaucoma-Hyphaema Syndrome. General review. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2017;61:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Elhusseiny AM, Lee RK, Smiddy WE. Surgical management of uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome. Int J Ophthalmol. 2020;13:935-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sen S, Zeppieri M, Tripathy K. Uveitis Glaucoma Hyphema Syndrome. 2024 Feb 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Niyadurupola N, Broadway DC. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma--a major review. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36:868-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mierlo CV, Pinto LA, Stalmans I. Surgical Management of Iatrogenic Pigment Dispersion Glaucoma. J Curr Glaucoma Pract. 2015;9:28-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Watt RH. Pigment dispersion syndrome associated with silicone posterior chamber intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1988;14:431-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tong N, Liu F, Zhang T, Wang L, Zhou Z, Gong H, Yuan F. Pigment dispersion syndrome and pigmentary glaucoma after secondary sulcus transscleral fixation of single-piece foldable posterior chamber intraocular lenses in Chinese aphakic patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43:639-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zeppieri M. Pigment dispersion syndrome: A brief overview. J Clin Transl Res. 2022;8:344-350. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kocová H, Vlková E, Michalcová L, Rybárová N, Motyka O. Incidence of cataract following implantation of a posterior-chamber phakic lens ICL (Implantable Collamer Lens) - long-term results. Cesk Slov Oftalmol. 2017;73:87-93. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Li Y, Liu J, Tian Q, Ma X, Zhao Y, Bi H. Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome combined with ectropion uveae and pigment dispersion syndrome: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e32869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chopra V, Arora S, Francis BA. Not a Routine Case ofPigmentary DispersionSyndrome or UveiticGlaucoma. Challeng Cases. 2015;18-21. |