Published online Sep 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i26.5952

Revised: June 15, 2024

Accepted: July 15, 2024

Published online: September 16, 2024

Processing time: 148 Days and 22.3 Hours

Adenocarcinoma is the most common subtype of prostate cancer. Prostatic urothelial carcinoma (UC) typically originates from the prostatic urethra. The concurrent occurrence of adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland is uncommon.

We present the case of an 82-year-old male patient with simultaneous adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland. The patient underwent a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy, and the pathology test revealed UC. Subsequently, transurethral laser prostatectomy was performed, and the pathology test indicated adenocarcinoma of the prostate with a Gleason score of 3 + 4 and high-grade UC. Therefore, the patient was treated with androgen deprivation therapy, systemic chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Magnetic resonance imaging performed during follow-up revealed a prostate tumor classified as cT2cN1M0, stage IVA. Therefore, the patient underwent robotic-assisted radical prosta

According to our literature review, this is the first reported case of coexisting adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland.

Core Tip: This report of synchronous adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the prostate gland describes the unique prostate cancer manifestations in a male patient as well as the clinical journey from his initial symptoms of urinary retention and gross hematuria to the final treatment comprising robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy and bilateral pelvic lymph nodes dissection. This rare co-occurrence of two distinct cancer subtypes of the prostate gland without a history of UC of the urinary bladder and evident recurrence after treatment emphasizes the need for heightened diagnostic awareness and suggests novel oncogenic pathways and genetic predispositions.

- Citation: Hsu JY, Lin YS, Huang LH, Tsao TY, Hsu CY, Ou YC, Tung MC. Concurrent occurrence of adenocarcinoma and urothelial carcinoma of the prostate gland: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(26): 5952-5959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i26/5952.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i26.5952

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer among men worldwide, and its incidence increases with age. The predominant subtype of carcinoma of the prostate is adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinoma is graded using the Gleason scoring system. Prostate urothelial carcinoma (UC) is a subtype that usually develops from the urothelium lining the prostatic urethra and the proximal sections of the prostatic ducts[1]. As far as we are aware, this is the first documented report of adenocarcinoma and UC co-occurring in the prostate gland.

An 82-year-old male patient presented to the urology clinic with a 5-day history of acute urinary retention and gross hematuria.

The patient experienced gross hematuria and intermittent acute urinary retention for 5 days before presentation.

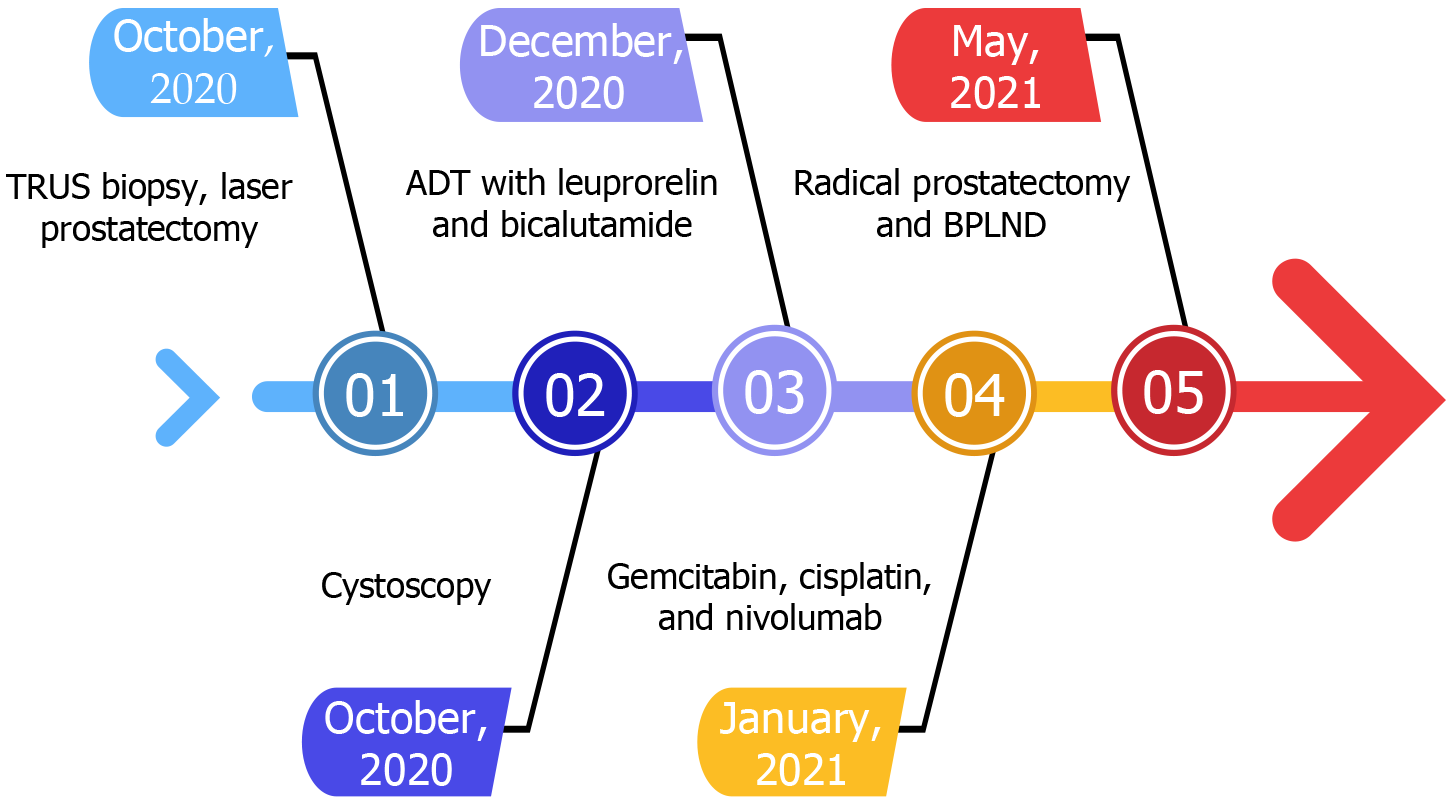

The patient was initially evaluated at another hospital because he experienced acute urinary retention and gross hematuria. A digital rectal examination (DRE) revealed firm prostate nodules and an increased prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level of 53 ng/mL. In October 2020, the patient underwent a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy that revealed UC. Subsequently, he underwent transurethral laser prostatectomy. The pathology test indicated prostatic adenocarcinoma with a Gleason score of 3 + 4 and high-grade UC. Cystoscopy revealed no papillary tumors in the prostatic urethra or urinary bladder. No evidence of bone metastasis was observed during a bone scan. Therefore, the patient was treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) with leuprorelin and bicalutamide in December 2020. In January and February 2021, the patient was treated with systemic chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin. In February 2021, the patient was treated with immunotherapy with nivolumab at another hospital (Figure 1).

The patient had a history of hypertension and arrhythmia that were controlled with medication. He did not have a family history of malignant tumors.

During the physical examination, the external genitalia appeared normal. The DRE revealed a firm prostate with an estimated volume of 25 cm3.

The preoperative blood test revealed a white blood cell count of 8.2 × 103/µL, hemoglobin level of 12.3 g/dL, platelet count of 263 × 103/µL, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase level of 21 IU/L, blood urea nitrogen level of 21 mg/dL, creatinine level of 1.01 mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate of 75, and PSA level of 8.877 ng/dL. The urinalysis results were within normal ranges.

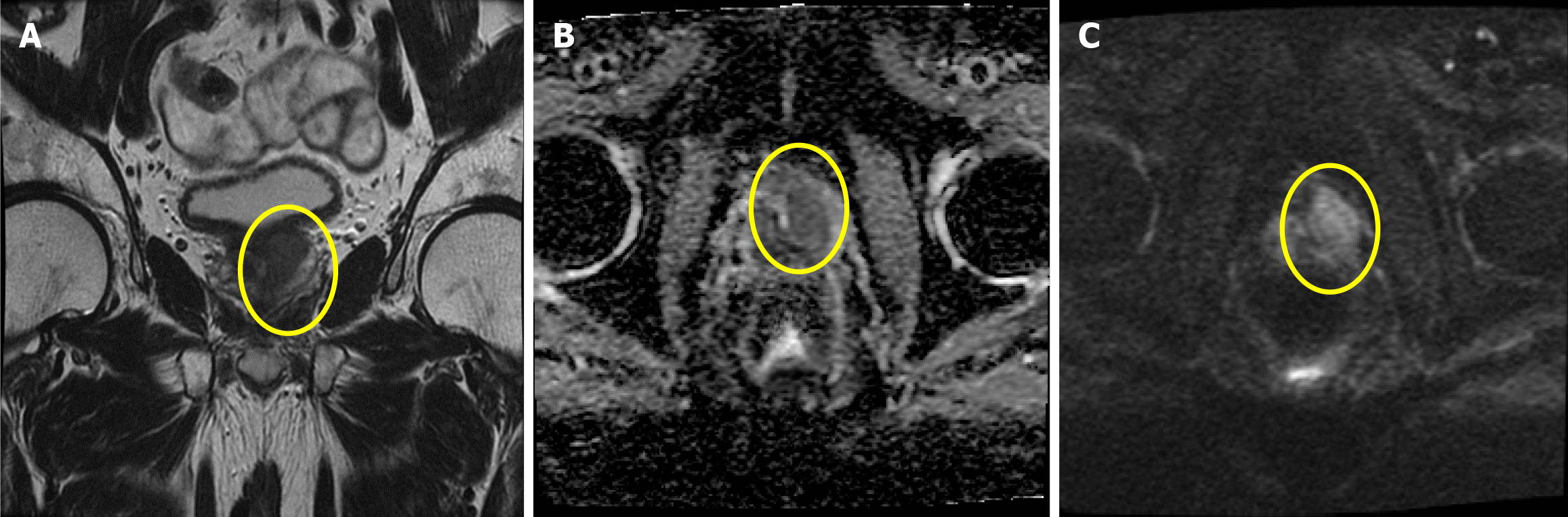

Ultrasonography was performed to estimate the volume of the prostate gland (25 cm3). The postvoid volume was 29 mL. Magnetic resonance imaging was performed during follow-up and revealed a prostate tumor classified as cT2cN1M0, stage IVA (Figure 2).

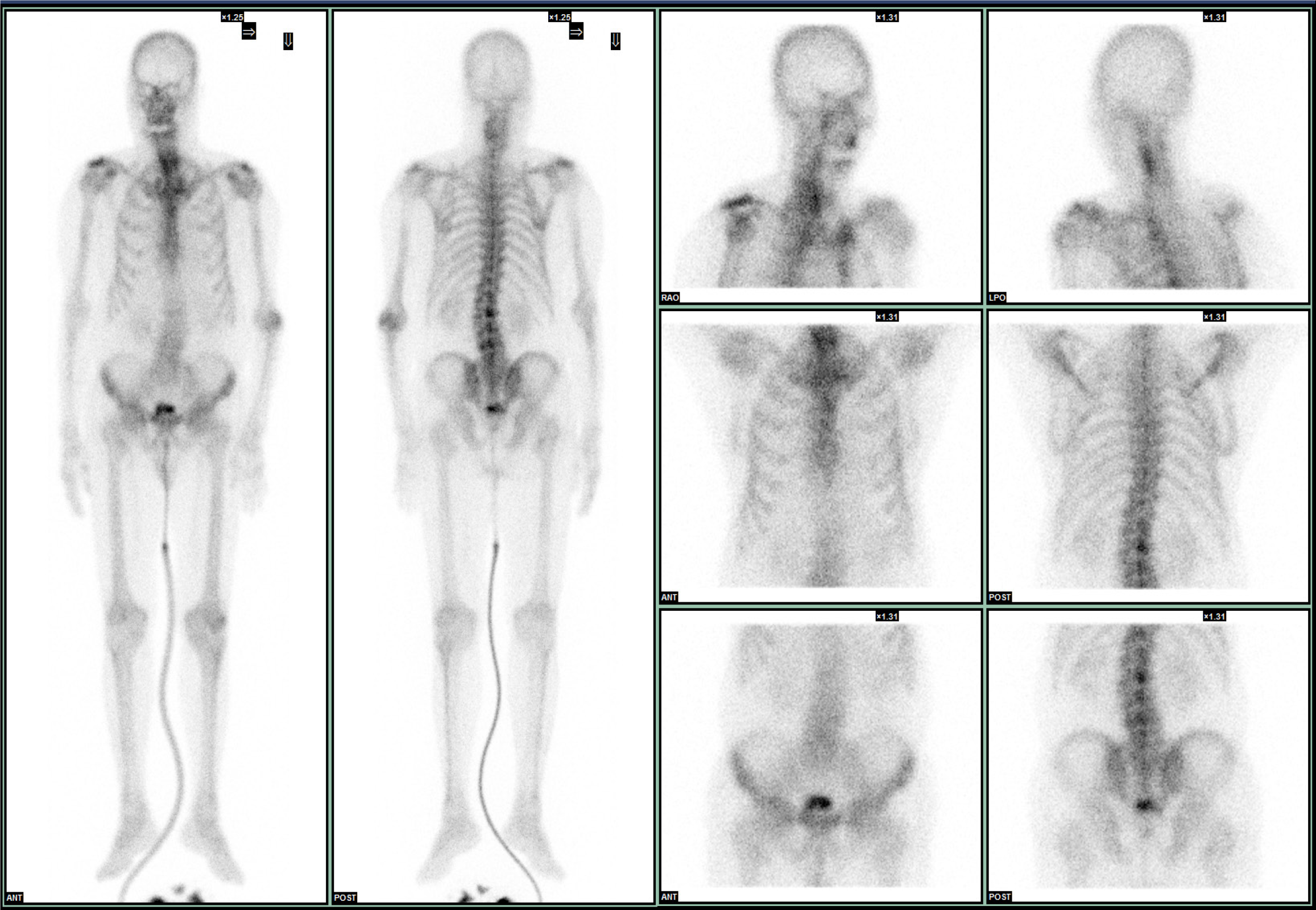

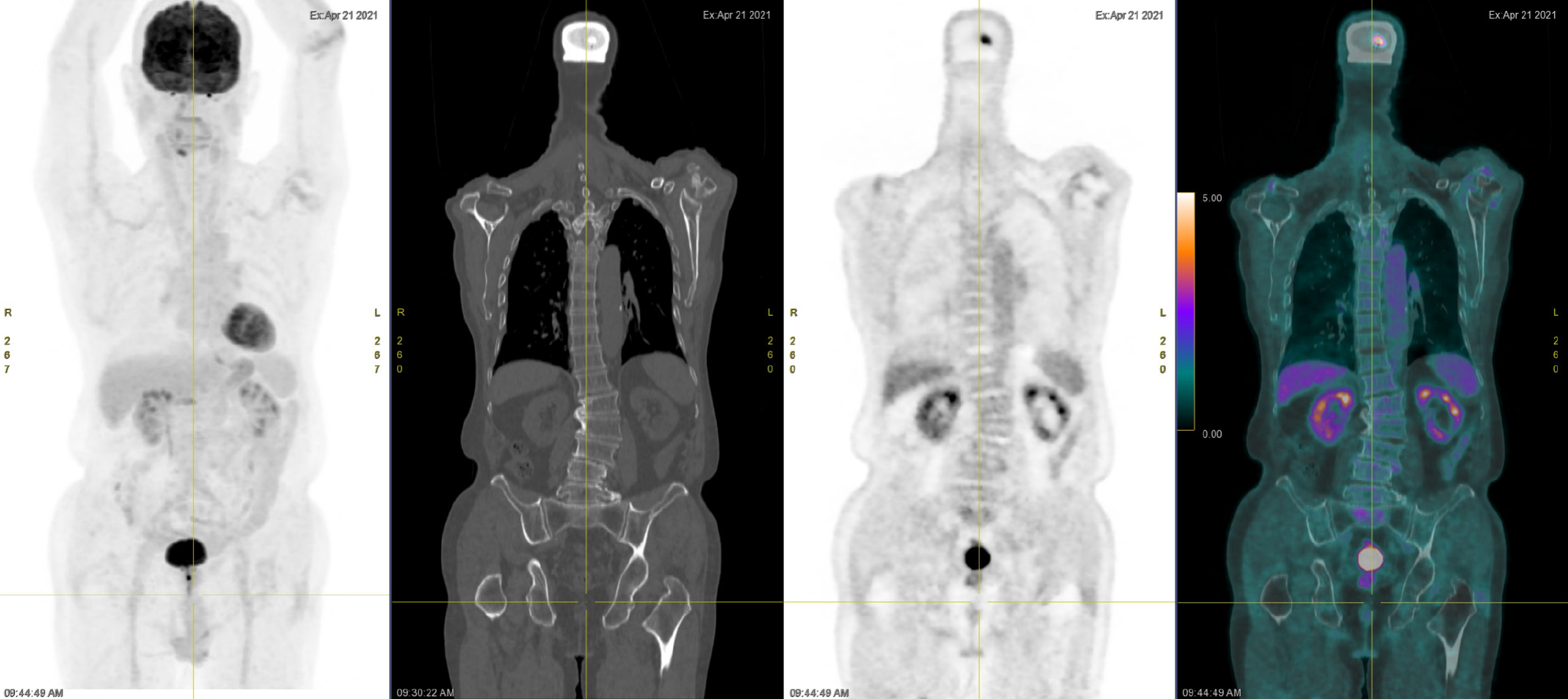

A technetium-99 m methylene diphosphonate whole-body bone scan revealed no evidence of bone metastasis (Figure 3). An 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography examination revealed no evidence of metastasis (Figure 4). Cystoscopy revealed no papillary tumors in the urinary bladder or urethra.

The final diagnosis was adenocarcinoma and high-grade UC of the prostate classified as cT2cN1M0, stage IVA.

The patient presented to our hospital for a second opinion regarding the diagnosis. Radical cystoprostatectomy was suggested; however, the patient refused this procedure. Therefore, he underwent robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RaRP) and bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection (BPLND) on May 11, 2021 (Figure 5).

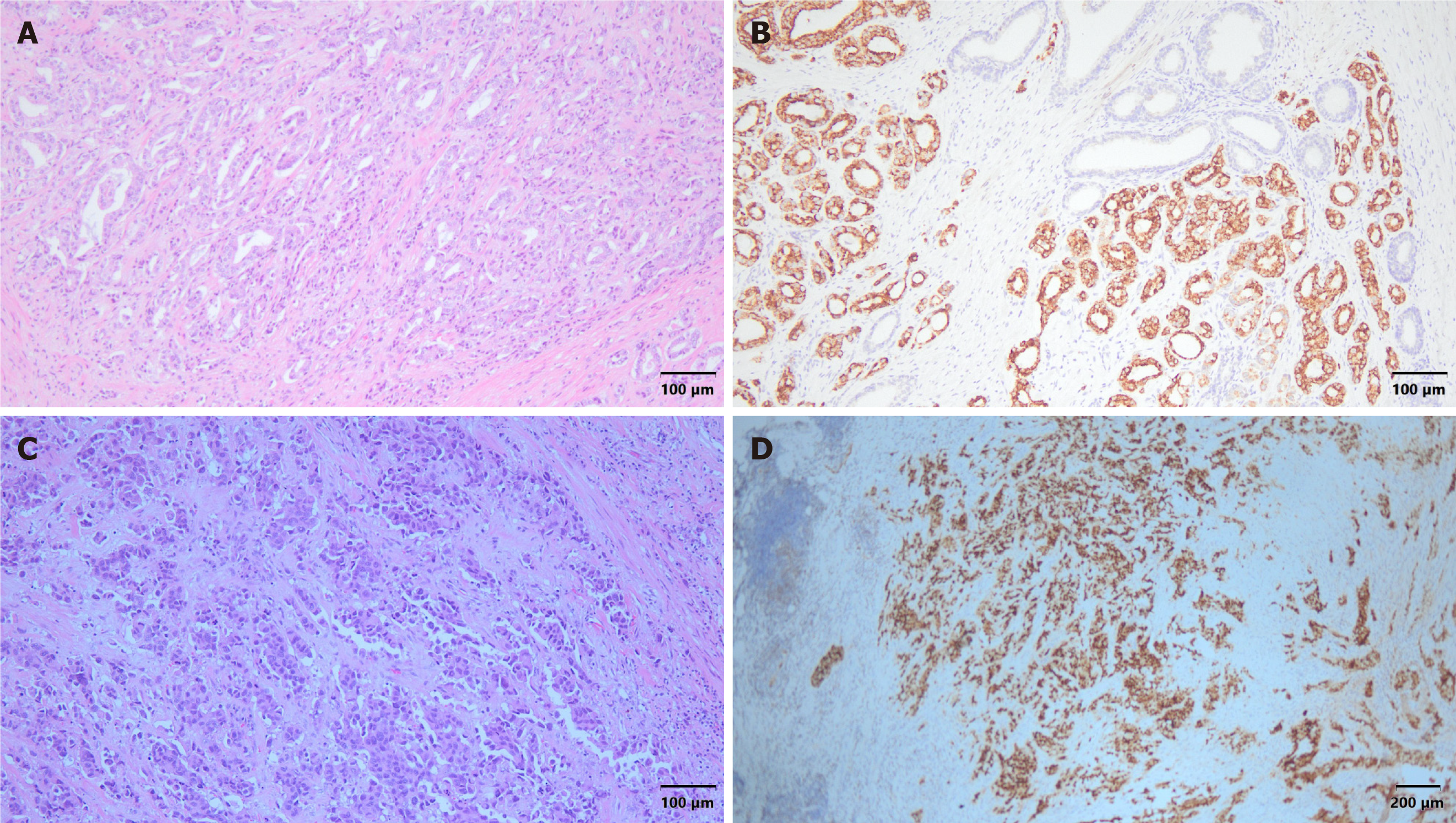

The results of the final pathology test of the prostate gland indicated acinar-type adenocarcinoma, gleason pattern 4 + 3 (grade group 3), pT2N0M0, and high-grade UC (Figure 6). The surgical margins were clear, and extraprostatic extension was not observed. The immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: Negative CK5; Positive α-methylacyl coenzyme A racemase; Positive synaptophysin (20%); and Positive GATA binding protein 3 (GATA3). These findings indicated concurrent adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland. The patient was discharged 6 days postoperatively. He experienced good recovery and did not report any major complications. Outpatient evaluations comprising PSA monitoring and cystoscopy were performed every 3 months. The PSA levels remained less than 0.008 ng/dL. Urinary discomfort and signs of recurrence were not observed during the most recent clinical evaluation. The patient expressed that he was highly satisfied with the surgical outcome and that his quality of life had significantly improved with treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of simultaneous adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland in Taiwan. Typically, prostate cancer manifests as adenocarcinoma. Although there have been case reports of adenocarcinoma and tubulovillous adenoma of the urinary bladder, UC predominantly occurs in the urinary bladder or ureter[2,3]. One of the primary objectives of this study was to stimulate further research into the mechanisms underlying the coexistence of these conditions.

According to the World Health Organization GLOBOCAN database, prostate cancer is a significant medical concern because of its prevalence, impact on the quality of life, and mortality. Risk factors include age, ethnicity, genetics, diet, hormones, obesity, and others[4-8]. Patients are often asymptomatic initially. Bone pain is a common clinical presentation among patients with metastatic prostate cancer at the time of diagnosis because the bones are the predominant sites of dissemination[9].

Prostate cancer is typically suspected when increased PSA levels or abnormal DRE findings are observed. There is no single threshold for abnormal PSA levels. However, age-specific reference PSA levels, which increase faster in older men, and the velocity of increase in the PSA level, which often has a cutoff of more than 0.75 ng/dL within 1 year, are considered significant findings[10].

A definitive diagnosis requires the evaluation of tissue samples obtained during a transrectal or transperineal biopsy[11]. Most malignant prostatic neoplasms are carcinomas that originate from and are differentiated from epithelial tissue. Adenocarcinoma, which accounts for more than 95% of all cases, is characterized by its glandular structure, absence of basal cells, and distinct nuclear characteristics of the glandular epithelial cells[12]. Compared to benign glands, malignant glands present more frequently with intraluminal crystalloids, amorphous secretions, or blue-tinged mucin. Adenocarcinomas are mostly acinar; the ductal types are less common[13]. UC, which is another less common subtype, typically occurs concurrently with bladder carcinoma; however, it can arise as the primary disease. Immunohistochemical findings that differentiate UC from adenocarcinoma of the prostate include thrombomodulin, GATA3, p63, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins[14].

The staging and evaluation of adenocarcinoma of the prostate as well as its treatment strategies are based on its risk stratification determined by the DRE results, serum PSA levels, pathology results of the prostate biopsy sample, and imaging results. Treatment options for very low-risk disease include active surveillance and, if necessary, definitive local therapy such as radiation therapy (RT) and radical prostatectomy[15]. Definitive treatment options for patients with low-risk prostate cancer and a life expectancy of more than 10 years include RT, radical prostatectomy, and active surveillance[16]. Intermediate-risk disease can be treated with RT and radical prostatectomy. Clinically localized high-risk prostate cancer is typically managed with external beam RT combined with brachytherapy, ADT, or radical prostatectomy[15]. Treatments for locally advanced and very high-risk prostate cancer include external beam RT with or without brachytherapy, long-term ADT, and radical prostatectomy[17]. The outcomes of these treatments depend on the disease stage and patient compliance.

A review of the literature indicated that most patients with UC of the prostate had a history of UC of the urinary bladder[18]. Additionally, concurrent UC of the urinary bladder and prostate was diagnosed incidentally after cystoprostatectomy[19,20]. In this case, UC was not observed in the urinary bladder. However, the coexistence of UC and adenocarcinoma of the prostate was incidentally discovered after the prostate biopsy. According to previous research of the different immunohistochemical findings that distinguish prostate carcinoma from UC, the sensitivities of prostatic markers of prostate adenocarcinoma were as follows: 100% for PSA; 83.8% for prostate-specific membrane antigen; 91.9% for prostate acid phosphatase; 93.7% for P501s; 88.3% for NKX 3.1; and 66.7% for α-methylacyl coenzyme a racemase. In contrast, the sensitivities of urothelial markers of UC were 75.4% for CK34βE12, 73.9% for p63, 45.7% for thrombo

We proposed three hypotheses regarding the potential mechanisms of synchronous adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate. First, metaplastic transformation may result in this phenomenon. Metaplastic transformation involves the conversion of one differentiated cell type to another. In this context, some glandular cells within the prostate may have undergone metaplastic transformation to urothelial cells, potentially driven by chronic inflammation or other local environmental factors[22]. Second, the presence of multipotent stem cells within the prostate could explain the coexistence of adenocarcinoma and UC. Multipotent stem cells can differentiate into various cell types, including glandular and urothelial cells. This pluripotency may lead to the simultaneous emergence of adenocarcinoma and UC in the same tissue[23,24]. Third, the intraluminal spread of UC cells from an occult site within the urinary tract to the prostate could cause this uncommon disease occurrence. Intraluminal spread can occur without a documented history of primary UC, particularly if the primary site is very small or has regressed[25]. Although these hypotheses provide various potential explanations for the simultaneous presence of adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate, they have not been confirmed.

Our patient initially underwent ADT for adenocarcinoma of the prostate because he preferred nonsurgical inter

Despite the absence of a history of UC in the urinary bladder, cystoscopy revealed no recurrence following ADT, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Two years after RaRP and BPLND, the patient was recurrence-free. No reports of synchronous adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland were found during our literature review.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of synchronous adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland. Although a correlation between adenocarcinoma and UC of the prostate gland has not been proven, this case highlights the potential for the coexistence of these two cancer subtypes in the prostate gland and suggests the need for further genetic studies and case reports to improve the understanding of the causes and mechanisms of their coexistence.

We extend our heartfelt appreciation to the patient for consenting to the publication of this case. We also express our special thanks to the staff of Tungs’ Taichung MetroHarbor Hospital for their exemplary care and dedication to patient service.

| 1. | Liedberg F, Chebil G, Månsson W. Urothelial carcinoma in the prostatic urethra and prostate: current controversies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:383-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tsai PH, Chiang HC, Chen PH. Adenocarcinoma of urinary bladder– A case report. Urol Sci. 2015;26:298. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen I, Chien C, Yu C, Wu T, Huang J. Primary tubulovillous adenoma of the urinary bladder: Case report and literature review. Urol Sci. 2014;25:139-142. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Parker PM, Rice KR, Sterbis JR, Chen Y, Cullen J, McLeod DG, Brassell SA. Prostate cancer in men less than the age of 50: a comparison of race and outcomes. Urology. 2011;78:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Barber L, Gerke T, Markt SC, Peisch SF, Wilson KM, Ahearn T, Giovannucci E, Parmigiani G, Mucci LA. Family History of Breast or Prostate Cancer and Prostate Cancer Risk. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5910-5917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chan JM, Gann PH, Giovannucci EL. Role of diet in prostate cancer development and progression. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8152-8160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group; Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, Key TJ. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:170-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 585] [Cited by in RCA: 534] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Allott EH, Masko EM, Freedland SJ. Obesity and prostate cancer: weighing the evidence. Eur Urol. 2013;63:800-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 32.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Collin SM, Metcalfe C, Donovan JL, Athene Lane J, Davis M, Neal DE, Hamdy FC, Martin RM. Associations of sexual dysfunction symptoms with PSA-detected localised and advanced prostate cancer: a case-control study nested within the UK population-based ProtecT (Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment) study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:3254-3261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oesterling JE, Jacobsen SJ, Chute CG, Guess HA, Girman CJ, Panser LA, Lieber MM. Serum prostate-specific antigen in a community-based population of healthy men. Establishment of age-specific reference ranges. JAMA. 1993;270:860-864. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Lin H, Huang C, Chang C, Chiu Y, Hsueh TY, Lu S, Chiu AW. The efficacy of transrectal prostate needle biopsy in older men. Urol Sci. 2016;27:S34-S35. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Humphrey PA. Histopathology of Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chow K, Bedő J, Ryan A, Agarwal D, Bolton D, Chan Y, Dundee P, Frydenberg M, Furrer MA, Goad J, Gyomber D, Hanegbi U, Harewood L, King D, Lamb AD, Lawrentschuk N, Liodakis P, Moon D, Murphy DG, Peters JS, Ruljancich P, Verrill CL, Webb D, Wong LM, Zargar H, Costello AJ, Papenfuss AT, Hovens CM, Corcoran NM. Ductal variant prostate carcinoma is associated with a significantly shorter metastasis-free survival. Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:440-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paner GP, Annaiah C, Gulmann C, Rao P, Ro JY, Hansel DE, Shen SS, Lopez-Beltran A, Aron M, Luthringer DJ, De Peralta-Venturina M, Cho Y, Amin MB. Immunohistochemical evaluation of novel and traditional markers associated with urothelial differentiation in a spectrum of variants of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:1473-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bekelman JE, Rumble RB, Chen RC, Pisansky TM, Finelli A, Feifer A, Nguyen PL, Loblaw DA, Tagawa ST, Gillessen S, Morgan TM, Liu G, Vapiwala N, Haluschak JJ, Stephenson A, Touijer K, Kungel T, Freedland SJ. Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement of an American Urological Association/American Society for Radiation Oncology/Society of Urologic Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3251-3258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA, Mason M, Metcalfe C, Walsh E, Blazeby JM, Peters TJ, Holding P, Bonnington S, Lennon T, Bradshaw L, Cooper D, Herbert P, Howson J, Jones A, Lyons N, Salter E, Thompson P, Tidball S, Blaikie J, Gray C, Bollina P, Catto J, Doble A, Doherty A, Gillatt D, Kockelbergh R, Kynaston H, Paul A, Powell P, Prescott S, Rosario DJ, Rowe E, Davis M, Turner EL, Martin RM, Neal DE; ProtecT Study Group*. Patient-Reported Outcomes after Monitoring, Surgery, or Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1425-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 917] [Article Influence: 101.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tsao CK, Gray KP, Nakabayashi M, Evan C, Kantoff PW, Huang J, Galsky MD, Pomerantz M, Oh WK. Patients with Biopsy Gleason 9 and 10 Prostate Cancer Have Significantly Worse Outcomes Compared to Patients with Gleason 8 Disease. J Urol. 2015;194:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pawar D, Arif D, Raghunath A, Rehman S. Urothelial carcinoma with mandibular metastasis and synchronous prostate cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Dell'Atti L. Relevance of prostate cancer in patients with synchronous invasive bladder urothelial carcinoma: a monocentric retrospective analysis. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2015;87:76-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sivalingam S, Drachenberg D. The incidence of prostate cancer and urothelial cancer in the prostate in cystoprostatectomy specimens in a tertiary care Canadian centre. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Oh WJ, Chung AM, Kim JS, Han JH, Hong SH, Lee JY, Choi YJ. Differential Immunohistochemical Profiles for Distinguishing Prostate Carcinoma and Urothelial Carcinoma. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50:345-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Humphrey PA. Histological variants of prostatic carcinoma and their significance. Histopathology. 2012;60:59-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lawson DA, Xin L, Lukacs R, Xu Q, Cheng D, Witte ON. Prostate stem cells and prostate cancer. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1967-2000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 719] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cohen RJ, Shannon BA, Weinstein SL. Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate gland with transmucosal spread to the seminal vesicle: a lesion distinct from high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1122-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |