Published online Sep 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i25.5821

Revised: June 12, 2024

Accepted: July 1, 2024

Published online: September 6, 2024

Processing time: 77 Days and 13.9 Hours

Pancreatic trauma (PT) is rare among traumatic injuries and has a low incidence, but it can still lead to severe infectious complications, resulting in a high mortality rate. Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common complication after PT, and when combined with organ dysfunction and sepsis, it will result in a poorer prognosis.

We report a 25-year-old patient with multiple organ injuries, including the pancreas, due to abdominal trauma, who developed necrotising pancreatitis secondary to emergency caesarean section, combined with intra-abdominal infection (IAI). The patient underwent performed percutaneous drainage, pancreatic necrotic tissue debridement, and abdominal infection foci debridement on the patient.

We report a case of severe AP and IAI secondary to trauma. This patient was managed by a combination of conservative treatment such as antibiotic therapy and fluid support with surgery, and a better outcome was obtained.

Core Tip: A complicated abdominal infection is associated with a very high mortality rate and is a difficult clinical problem. We report a critically ill patient with a complex abdominal infection due to trauma who successfully recovered after conservative treatment and surgery.

- Citation: Zhang Y, Cui YF. Severe acute pancreatitis complicated with intra-abdominal infection secondary to trauma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(25): 5821-5831

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i25/5821.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i25.5821

Pancreatic injury is an uncommon injury caused by abdominal trauma, with an incidence of less than 1%, accounting for 3.7%-11% of abdominal trauma and a mortality rate of 9%-34%[1,2]. Pancreatic injury caused by blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma, post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), or after pancreatic surgery is most often secondary to acute pancreatitis (AP) with intra-abdominal infection (IAI)[3]. Also, when AP is combined with complications and persistent organ failure, patients are susceptible to infection, leading to poorer clinical outcomes. Moreover, complicated abdominal infection (cIAI) can lead to peritonitis, which in turn can be followed by sepsis, infectious shock, and multiple organ failure, ultimately leading to death[4]. Therefore, controlling and eliminating the infection promptly and correctly is essential.

We report a patient with abdominal trauma who developed severe IAI and necrotising pancreatitis after undergoing an emergency caesarean section. The patient's treatment course is described and the relevant literature is briefly reviewed.

A 25-year-old male who fell while riding a motorised bicycle sustained abdominal, thoracic and head trauma, and was subsequently admitted to an outside hospital.

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen suggested fracture of the left 3rd-7th ribs and the right 7th-9th ribs, injury of the left lobe of the liver, periportal accumulation of blood and fluid, rupture of the spleen not excepted, pancreatic injury not excepted, accumulation of blood and fluid in the abdominal cavity and a large amount of non-coagulated blood due to abdominal perforation. Laparoscopy was carried out to examine the abdomen, and revealed the following: Transverse colon hepatic flexure rupture, traumatic multiple liver ruptures with bleeding, pancreatic neck partially dissected with bleeding, greater omentum and right anterior renal fascia rupture with bleeding, right epigastric abdominal wall peritoneum and transverse abdominal rupture. The patient underwent intermediate open transverse colon hepatic resection, distal closure, ascending colostomy, repair of multiple liver ruptures; pancreatic neck suture, the greater omentum and anterior renal fascia rupture repair. Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for tracheal intubation and ventilator-assisted respiration, and developed anuria with persistent elevation of creatinine, and was treated with bedside continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Due to aggravation of the disease, the patient was transferred to the ICU of another hospital, where she continued to be treated with anti-infection, CRRT, fluid support and respiratory support, and a tracheotomy was performed. The patient continued to have a fever; sputum culture and incisional swab culture suggested multiple drug-resistant bacteria, and repeat CT showed a suspected contusion of S4 of the left liver lobe and head of the pancreas. Bilateral pleural effusion, peritoneal effusion, gallbladder blood accumulation, and bilateral lung contusion are considered complex abdominal infections; drainage fluid amylase elevation was considered, and the existence of a pancreatic fistula was considered. The patient was transferred to our hospital 25 days after surgery for further treatment.

Be healthy before.

Denied history of hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebral infarction, hepatitis, tuberculosis and other infectious diseases, other trauma, surgery and blood transfusion. Denied history of food and drug allergy. The patient denied the history of unclean coitus; smoking for more than 6 years, with an average of 10 cigarettes/day, and drinking for more than 5 years, with 2 bottles of beer/day. The patient was advised to stop smoking and drinking. Denied any family history of hereditary disease.

Physical examinations showed that the patient was in an agitated tracheotomy state, the abdomen was slightly distention, no gastrointestinal or peristaltic waves were observed, multiple healed drainage tube areas were visible, the fistula port was visible in the right epigastric region with the fistula bag in place, approximately 100 mL of faeces-like fluid was seen in the bag, the abdomen was soft, abdominal tenderness was present with pressure pain throughout the abdomen. There was no rebound tenderness and muscle tension, the liver and spleen were not palpated, Murphy's sign, hepatic tachypnea and mobile turbidity were negative, and intestinal sounds were slightly weakened. The abdominal wall incision was split, and yellow fluid was seen oozing out.

Laboratory examinations on admission showed the following: Direct bilirubin 16.43 μmol/L, total bilirubin 29.62 μmol/L, albumin 29.5 g/L, lactate dehydrogenase) 262 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 8.71 mmol/L white blood cell count 12.38 × 109/L, lymphocytes% 7.7%, haemoglobin 84 g/L presence of liver insufficiency, renal insufficiency, hypoproteinaemia, anaemia, and elevated inflammatory parameters.

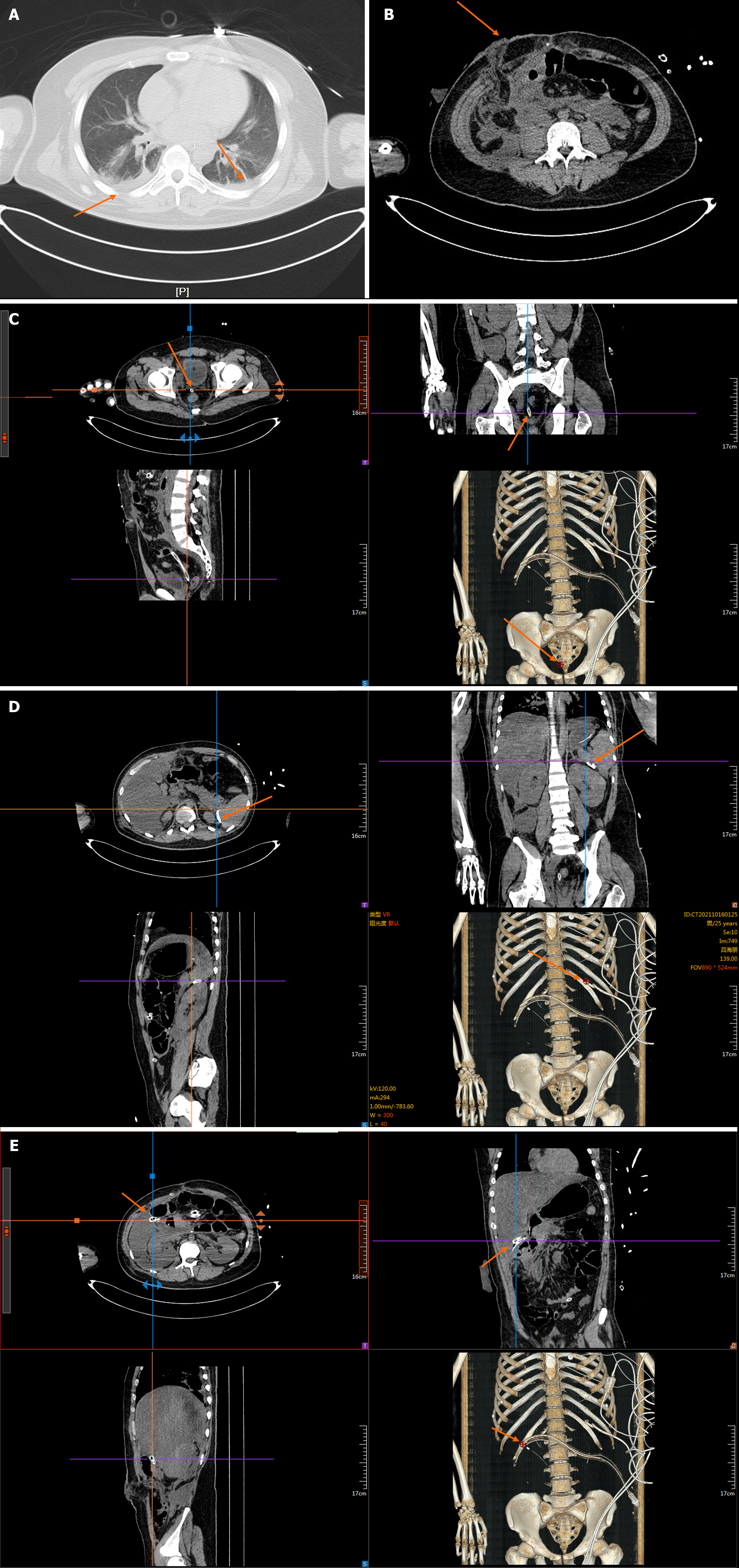

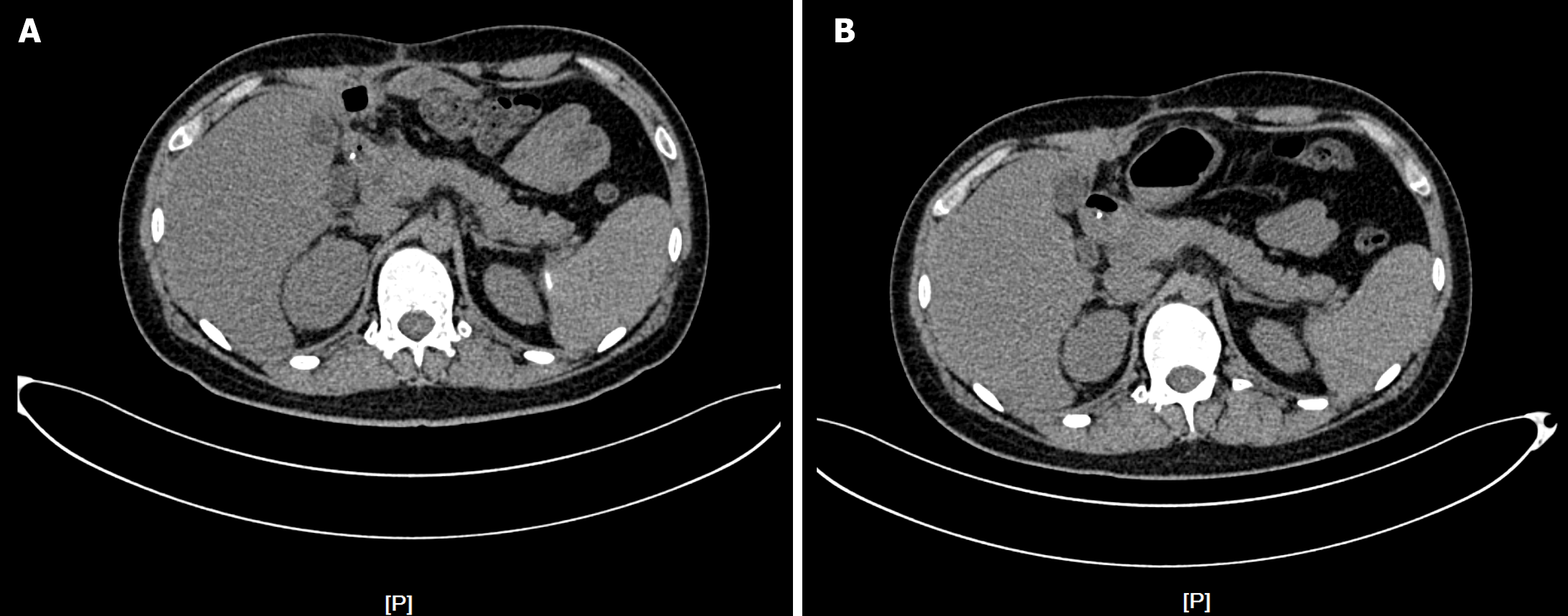

Chest and abdominal CT findings on admission are shown in Figure 1.

The patient was diagnosed with the following: Abdominal infection, pancreatic fistula, severe AP, traumatic pancreatic rupture, coagulation disorders, pneumonia, enterocutaneous fistula, post-operative wound dehiscence, colostomy status, hepatic insufficiency, hyperbilirubinaemia, elevated blood glucose, electrolyte disorders, hyperammonaemia, anaemia, renal function abnormalities and post-tracheotomy state.

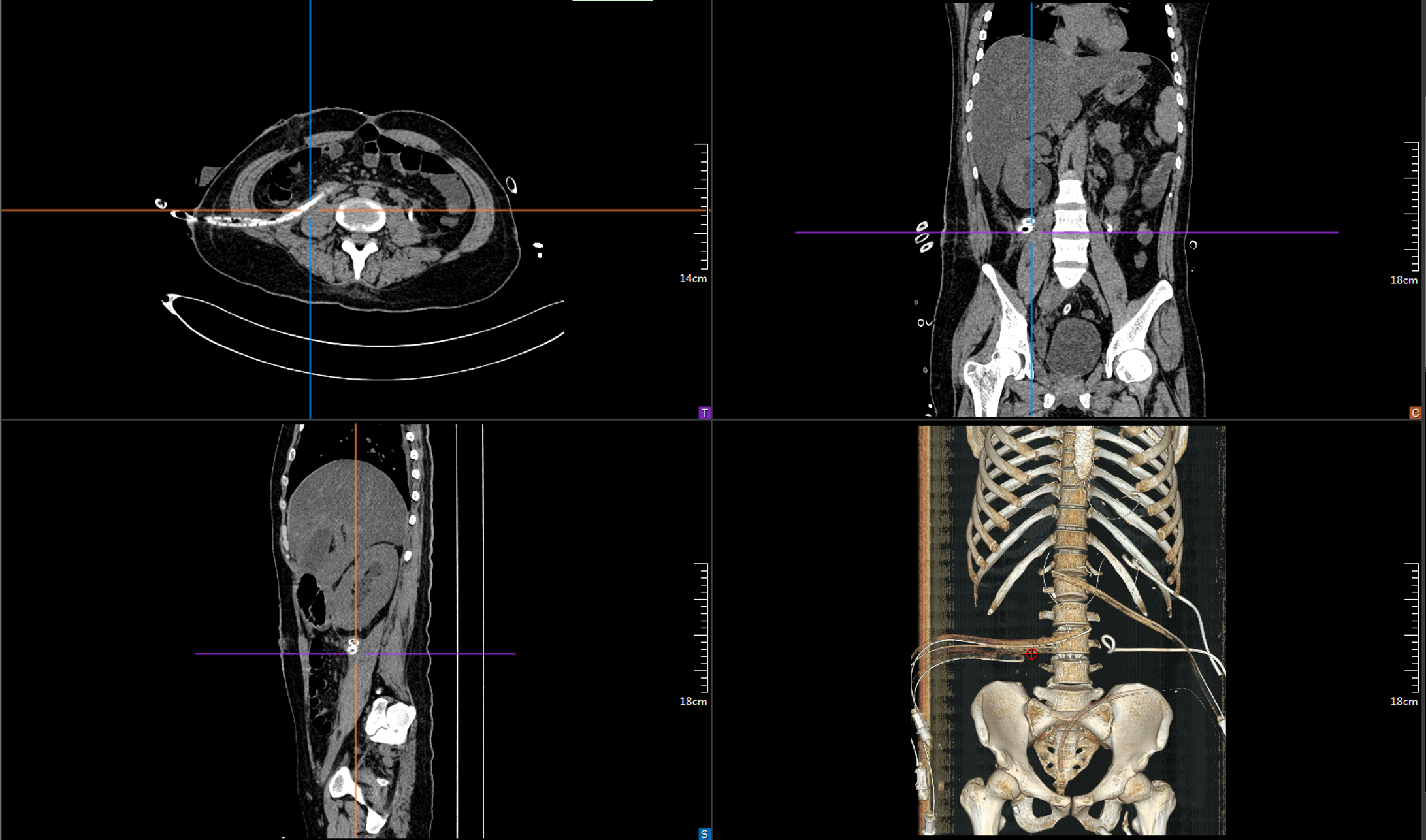

The patient was admitted in a critical condition, with agitation and hypoxaemia, and was transferred to the ICU for critical monitoring, during which time she received gastrointestinal decompression, ventilator-assisted respiration at the tracheotomy, and urinary catheterisation. The patient had abdominal infections and pulmonary infections, and was given antibiotic therapy based on the results of the drainage fluids, blood and sputum cultures, as well as symptomatic supportive treatments, such as fluid support, acid inhibition, enzyme inhibition, hepatoprotection, sputum elimination and nutritional support, with multiple percutaneous perforations and drainage of peritoneal fluid for abdominal effusion (Figure 2). The patient was treated in the ICU for a total of 8 days and was then transferred back to our department after her condition stabilized.

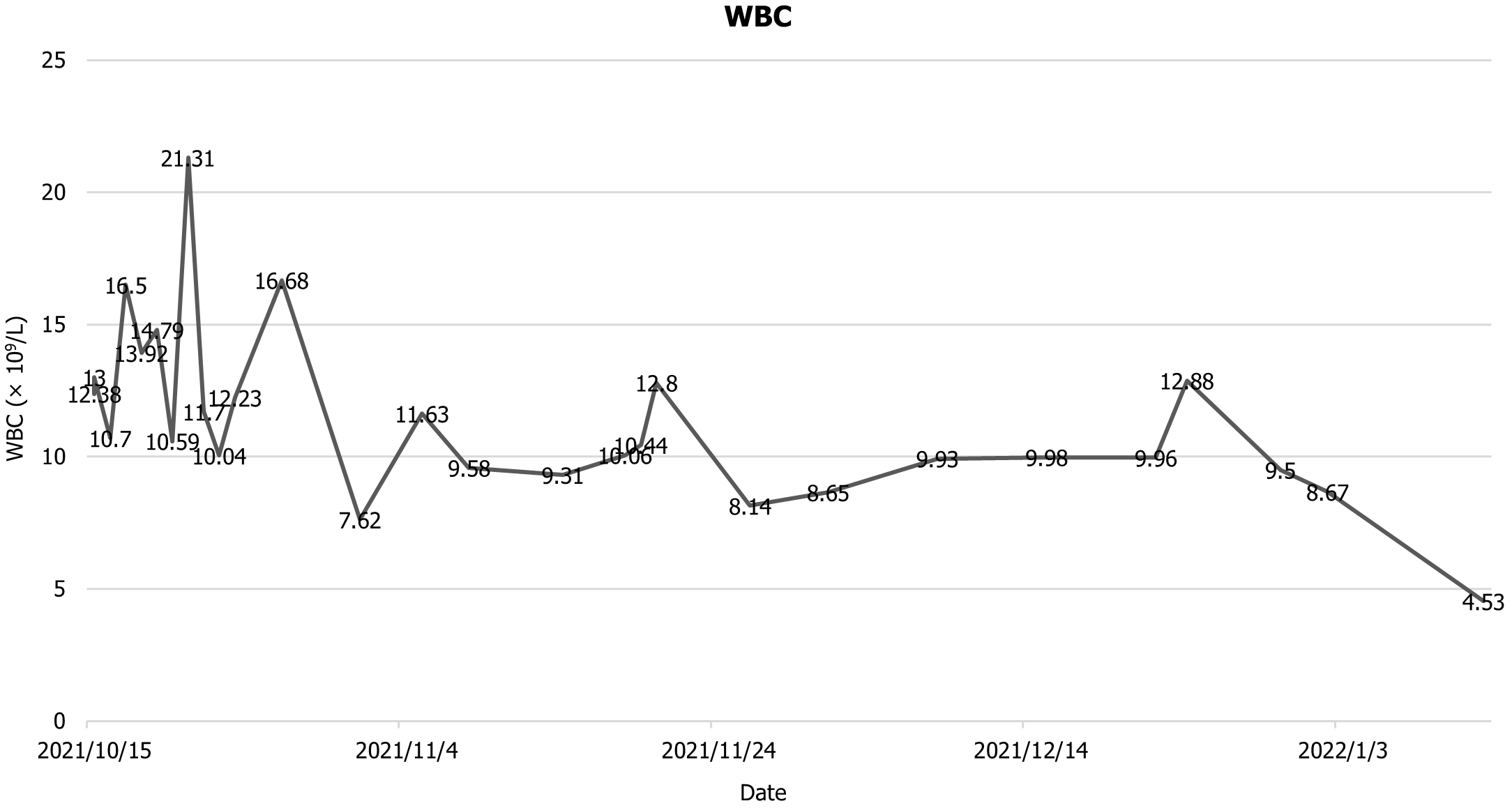

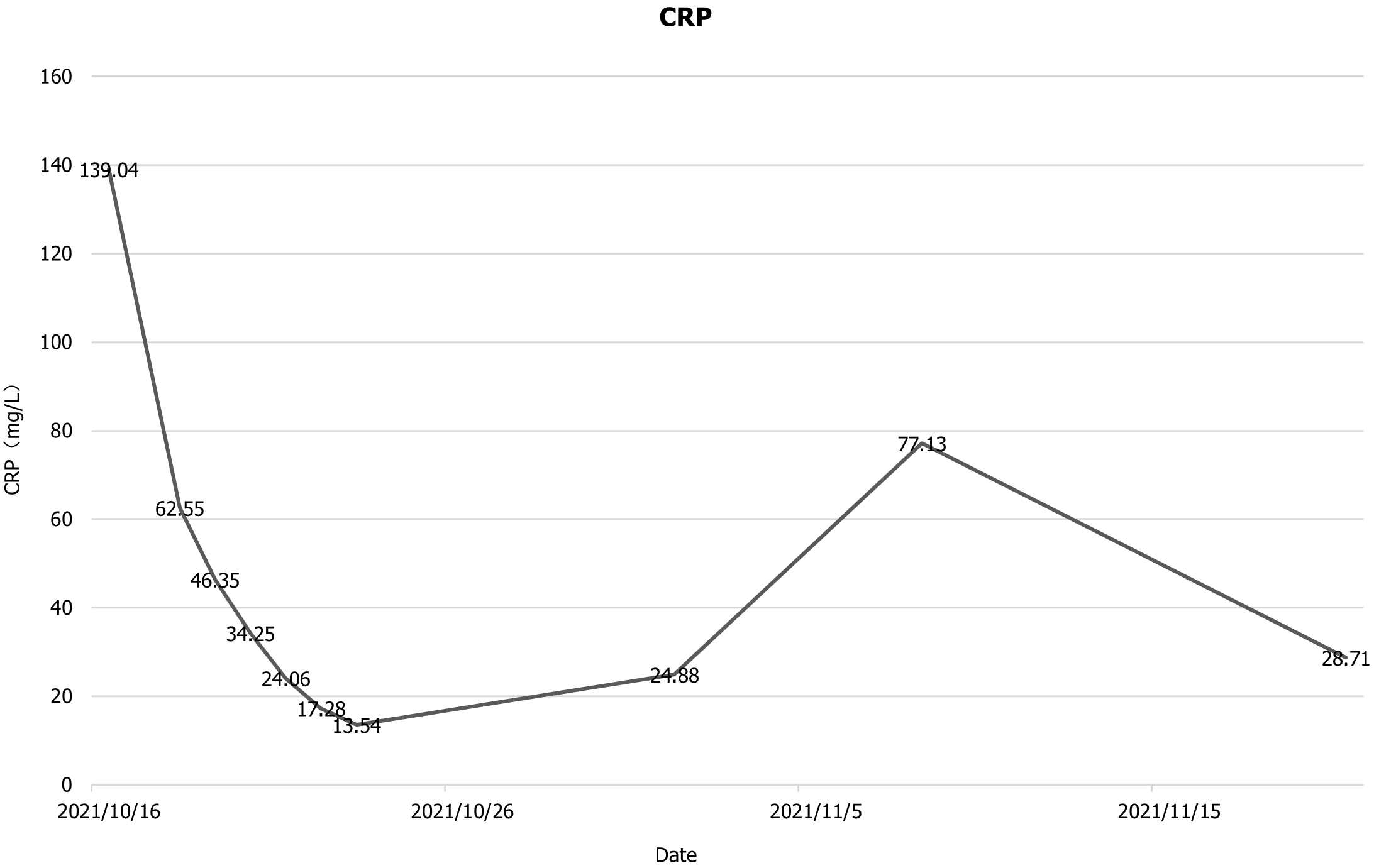

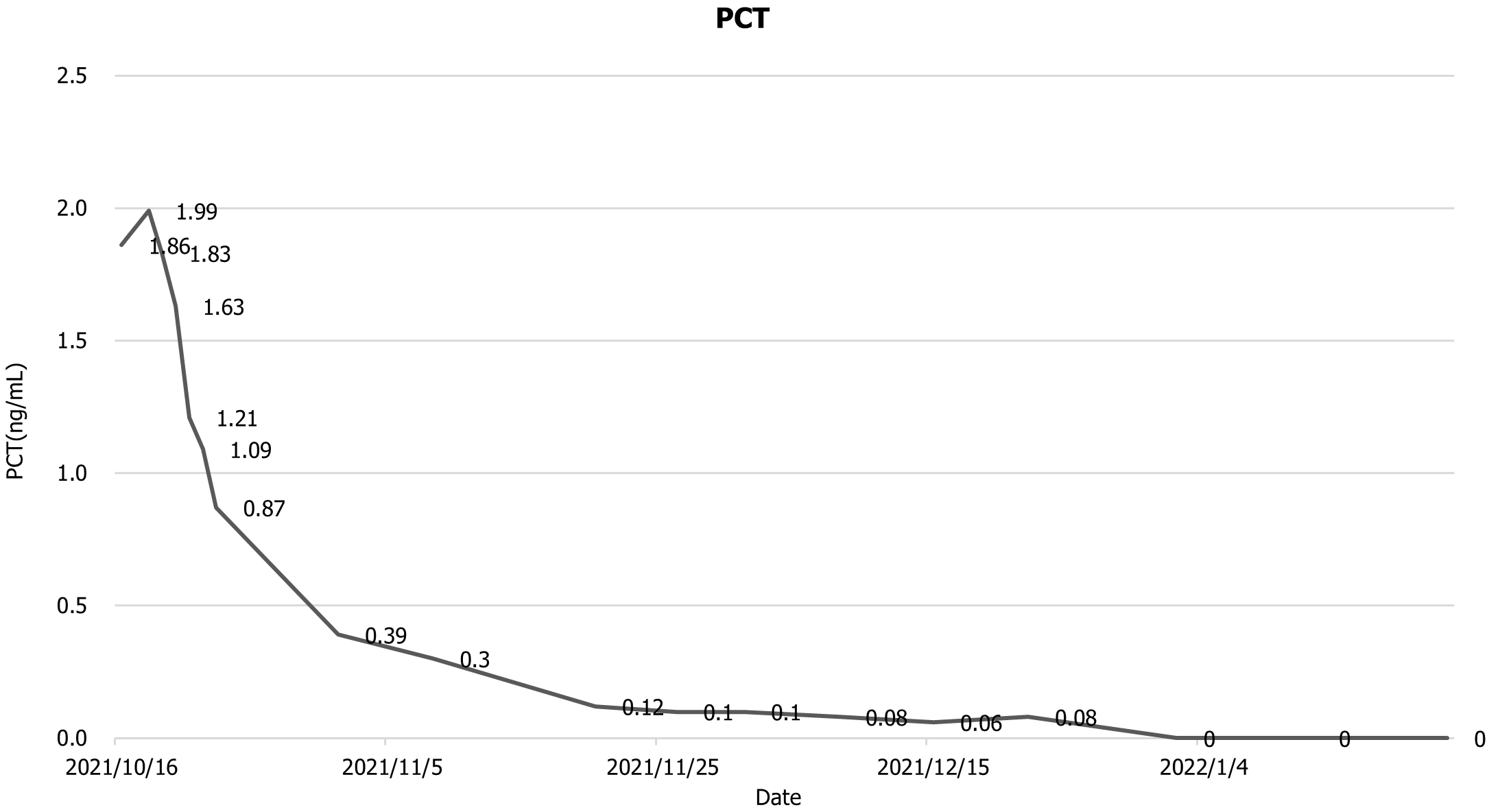

The patient was then transfer back to our department, and the drainage fluid culture results suggested that the infection was still present, and she continued to be treated with anti-infection, acid suppression, enzyme suppression, intravenous rehydration therapy, enteral nutritional support, along with continuous flushing and drainage via the drainage tubes. During the 6th week after admission, necrotic tissue debridement surgery and abscess debridement surgery were performed (the drains placed during surgery are shown in Figure 3) after evaluating the surgical risk. Weekly CT scans were then performed to assess the abdominal infection. Reoperation was performed to remove necrotic tissues and abscesses based on the results of the CT scan, and 24 h of continuous negative pressure flushing of the abdominal cavity was conducted after each operation (changes in infection indicators during the patient's stay in the hospital are shown in Figures 4-6).

With regard to our team's surgical procedure, for patients with abdominal infections admitted to our department, we first perform puncture drainage of the infected cavity after evaluating the patient's infection status, and continue conservative treatment for patients whose clinical symptoms improve after puncture drainage. Further puncture drainage or surgery is conducted for those who do not improve. After surgery, the patient receives continuous negative pressure flushing through the drainage tube. Thereafter, patients are re-examined every 7 days, and repeated minimally invasive debridement is performed in patients whose clinical symptoms and infections do not improve; for patients whose surgical clearance is unsatisfactory, repeat puncture drainage is performed; for bleeding and other complications, appropriate surgical treatments are performed, such as angiography, caesarean section, etc.; and for patients who recover after surgery, the drainage tube is gradually removed (Figure 7).

The patient was discharged from the hospital and was regularly reviewed in the outpatient clinic (Figure 8). All drains were finally removed after 1 year. Two years later, the patient underwent successful colostomy restitution in another department and returned to his social life.

Due to the particular anatomical location of the pancreas, isolated pancreatic injuries are rare, and many patients with pancreatic injuries have multiple associated injuries, including vascular and other intra-abdominal organ injuries. When patients suffer acute post-traumatic pancreatitis secondary to trauma, the mortality rate can be up to 40%[5]. When isolated pancreatic trauma (PT) without secondary pancreatitis is present, classification of injury severity and early diagnosis of possible pancreatic ductal injury is crucial to inform the choice of further therapeutic options at a later stage. For pancreatic injury severity, the most commonly used classification is that proposed by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) (Table 1)[6].

| Grade1 | Injury type | Injury description |

| I | Hematoma | Minor contusion without ductal injury |

| Laceration | Superficial laceration without ductal injury | |

| II | Hematoma | Major contusion without ductal injury or tissue loss |

| Laceration | Major laceration without ductal injury or tissue loss | |

| III | Laceration | Distal transection or parenchymal injury with duct injury |

| IV | Laceration | Proximal2 transection or parenchymal injury involving ampulla |

| V | Laceration | Massive disruption of pancreatic head |

Regardless of the choice of treatment for PT, whether conservative or surgical, it is essential to evaluate the patient's haemodynamic status, pancreatic injury, and other related injuries[2,3]. Patients with abdominal trauma, multiple organ injuries, and haemodynamic instability should be treated with immediate damage control surgery. According to the AAST classification of the degree of pancreatic injury, most patients had grade I and II injuries (60% and 20%, respectively)[7]. Patients with grades I and II who are haemodynamically stable and have no other associated injuries can be treated with non-operatively management, which includes intestinal rest, drainage, nutritional support, serial abdominal examinations, serial serum amylase measurements and imaging studies. Surgical treatment is recommended for patients with grade III and above. The most commonly used surgical modalities include external drainage, pancreatectomy and drainage, distal pancreatectomy, pancreatico-jejunoanostomy or pancreaticogastric anastomoses, Roux-en-Y reconstruction and pancreaticoduodenectomy as these procedures are for reconstruction. In addition, ERCP has been proposed in recent years as a therapeutic tool in addition to diagnosis, and trans nipple stents have helped to improve drainage in patients with massive post-traumatic pancreatic fistulae. However, ERCP carries a risk of postoperative pancreatitis, and stent placement may not be successful, or pancreatography may be inadequate in 9%-14% of patients[2,3,8]. According to a literature review, most patients were treated with drainage, and a small percentage of grade IV and V patients underwent the Whipple procedure[9]. However, the management of pancreatic injuries is still controversial, and there are no established protocols on whether and how to drain patients with grade I and II injuries, or on whether and how to operate in patients with grade III and higher injuries. More research is needed to standardise the management of pancreatic injuries.

IAI is a common and clinically severe infection that leads to a high mortality rate. Multiple guidelines state that source control is critical in managing IAIs[10-12]. Source control first requires identifying the cause and source of infection early and correctly. Biomarkers such as procalcitonin and C-creative protein have been widely used in clinical practice to assist in the diagnosis of infections[13]. In addition, ultrasound (US), CT and other imaging tests can also help to identify the source of infection[14]. Secondly, the method used to control the source of infection and the timing of the control are also significant. Surgical and non-surgical options are available for source control. Non-surgical options include percutaneous drainage, and US- and CT-guided percutaneous perforation drainage have been shown to be effective in some patients. Surgical intervention is currently the preferred option for controlling severe infections. Usually, this involves removal of the infected organ, necrotic tissue debridement, and repair or resection of the damaged viscus[10]. A meta-analysis showed a significant increase in patient mortality with delayed control of the source of the infection[15]. In addition, antibiotic therapy in patients with cIAI while controlling the source of infection is also an essential point in the principle of IAI treatment[16].

In the present case, the patient was unable to tolerate surgery due to poor organ function when she was transferred to our hospital; therefore, she was first transferred to the ICU for treatment, where CT-guided percutaneous perforation and drainage were carried out. When the patient's condition stabilised, she was transferred back to our department and underwent surgical treatment, during which necrotic tissues and abscesses were removed, and she was treated postoperatively with continuous peritoneal drainage. The patient was subsequently admitted to our department several times to review the planned staged pancreatic necrotic tissue removal, abscess debridement, and drainage. As the patient's gastrointestinal function gradually recovered and drainage fluid decreased, the drain was gradually removed according to CT and laboratory examination guidance.

We report a case of severe AP and IAI secondary to trauma and caesarean section. The patient suffered multiple abdominal organ injuries, including the pancreas, as a result of abdominal trauma and developed severe IAI secondary to caesarean section. During treatment, the IAI and organ dysfunction were managed by a combination of conservative and surgical treatments, which resulted in a positive outcome and allowed the patient to return to his social life.

| 1. | Debi U, Kaur R, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sinha A, Singh K. Pancreatic trauma: a concise review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9003-9011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coccolini F, Kobayashi L, Kluger Y, Moore EE, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Leppaniemi A, Augustin G, Reva V, Wani I, Kirkpatrick A, Abu-Zidan F, Cicuttin E, Fraga GP, Ordonez C, Pikoulis E, Sibilla MG, Maier R, Matsumura Y, Masiakos PT, Khokha V, Mefire AC, Ivatury R, Favi F, Manchev V, Sartelli M, Machado F, Matsumoto J, Chiarugi M, Arvieux C, Catena F, Coimbra R; WSES-AAST Expert Panel. Duodeno-pancreatic and extrahepatic biliary tree trauma: WSES-AAST guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sharbidre KG, Galgano SJ, Morgan DE. Traumatic pancreatitis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:1265-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Boldingh QJ, de Vries FE, Boermeester MA. Abdominal sepsis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Girard E, Abba J, Cristiano N, Siebert M, Barbois S, Létoublon C, Arvieux C. Management of splenic and pancreatic trauma. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:45-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, Jurkovich GJ, Champion HR, Gennarelli TA, McAninch JW, Pachter HL, Shackford SR, Trafton PG. Organ injury scaling, II: Pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma. 1990;30:1427-1429. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Iacono C, Zicari M, Conci S, Valdegamberi A, De Angelis M, Pedrazzani C, Ruzzenente A, Guglielmi A. Management of pancreatic trauma: A pancreatic surgeon's point of view. Pancreatology. 2016;16:302-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Potoka DA, Gaines BA, Leppäniemi A, Peitzman AB. Management of blunt pancreatic trauma: what's new? Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2015;41:239-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Petrone P, Moral Álvarez S, González Pérez M, Ceballos Esparragón J, Marini CP. Pancreatic trauma: Management and literature review. Cir Esp. 2017;95:123-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sartelli M, Coccolini F, Kluger Y, Agastra E, Abu-Zidan FM, Abbas AES, Ansaloni L, Adesunkanmi AK, Atanasov B, Augustin G, Bala M, Baraket O, Baral S, Biffl WL, Boermeester MA, Ceresoli M, Cerutti E, Chiara O, Cicuttin E, Chiarugi M, Coimbra R, Colak E, Corsi D, Cortese F, Cui Y, Damaskos D, De' Angelis N, Delibegovic S, Demetrashvili Z, De Simone B, de Jonge SW, Dhingra S, Di Bella S, Di Marzo F, Di Saverio S, Dogjani A, Duane TM, Enani MA, Fugazzola P, Galante JM, Gachabayov M, Ghnnam W, Gkiokas G, Gomes CA, Griffiths EA, Hardcastle TC, Hecker A, Herzog T, Kabir SMU, Karamarkovic A, Khokha V, Kim PK, Kim JI, Kirkpatrick AW, Kong V, Koshy RM, Kryvoruchko IA, Inaba K, Isik A, Iskandar K, Ivatury R, Labricciosa FM, Lee YY, Leppäniemi A, Litvin A, Luppi D, Machain GM, Maier RV, Marinis A, Marmorale C, Marwah S, Mesina C, Moore EE, Moore FA, Negoi I, Olaoye I, Ordoñez CA, Ouadii M, Peitzman AB, Perrone G, Pikoulis M, Pintar T, Pipitone G, Podda M, Raşa K, Ribeiro J, Rodrigues G, Rubio-Perez I, Sall I, Sato N, Sawyer RG, Segovia Lohse H, Sganga G, Shelat VG, Stephens I, Sugrue M, Tarasconi A, Tochie JN, Tolonen M, Tomadze G, Ulrych J, Vereczkei A, Viaggi B, Gurioli C, Casella C, Pagani L, Baiocchi GL, Catena F. WSES/GAIS/SIS-E/WSIS/AAST global clinical pathways for patients with intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mazuski JE, Tessier JM, May AK, Sawyer RG, Nadler EP, Rosengart MR, Chang PK, O'Neill PJ, Mollen KP, Huston JM, Diaz JJ Jr, Prince JM. The Surgical Infection Society Revised Guidelines on the Management of Intra-Abdominal Infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18:1-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sartelli M, Catena F, Coccolini F, Pinna AD. Antimicrobial management of intra-abdominal infections: literature's guidelines. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:865-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Tian BWCA, Agnoletti V, Ansaloni L, Coccolini F, Bravi F, Sartelli M, Vallicelli C, Catena F. Management of Intra-Abdominal Infections: The Role of Procalcitonin. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Laméris W, van Randen A, van Es HW, van Heesewijk JP, van Ramshorst B, Bouma WH, ten Hove W, van Leeuwen MS, van Keulen EM, Dijkgraaf MG, Bossuyt PM, Boermeester MA, Stoker J; OPTIMA study group. Imaging strategies for detection of urgent conditions in patients with acute abdominal pain: diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ. 2009;338:b2431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Song SR, Liu YY, Guan YT, Li RJ, Song L, Dong J, Wang PG. Timing of surgical operation for patients with intra-abdominal infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2023;15:2320-2330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | A Global Declaration on Appropriate Use of Antimicrobial Agents across the Surgical Pathway. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2017;18:846-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |