INTRODUCTION

Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE) is a severe neurological disorder caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, characterized primarily by the classic triad of mental status changes, ocular dysfunction, and ataxic gait. However, only a minority of cases present with the complete triad[1], which undoubtedly affects the timely diagnosis of the disease. The onset of WE is often associated with excessive alcohol intake. Still, it can also occur in other situations that may cause thiamine deficiency, including bariatric surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, repeated vomiting, or hypermetabolic states[2]. Currently, there is no evidence to suggest a direct association between WE and non-alcoholic factors, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC)[3]. NPC, which originates from the epithelial cells of the nasopharyngeal mucosa, exhibits a marked imbalance in its incidence across different geographical regions, being particularly prevalent in East and Southeast Asia[4]. This regional high-incidence phenomenon is closely associated with the geographic specificity of high-risk Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) subtypes[5,6]. Chemotherapy combined with radiotherapy is the primary treatment modality for locally advanced NPC[7]. Additionally, multiple studies have shown that induction chemotherapy combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy can significantly improve the 10-year overall survival, progression-free survival, and reduce the rate of distant metastasis[8]. This report describes the diagnostic and therapeutic process, clinical manifestations, and imaging characteristics of a male patient with NPC who developed WE after concurrent chemoradiotherapy, with no history of alcohol abuse. We have followed the CARE guidelines[9] in reporting this case and obtained the patient’s consent for treatment.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

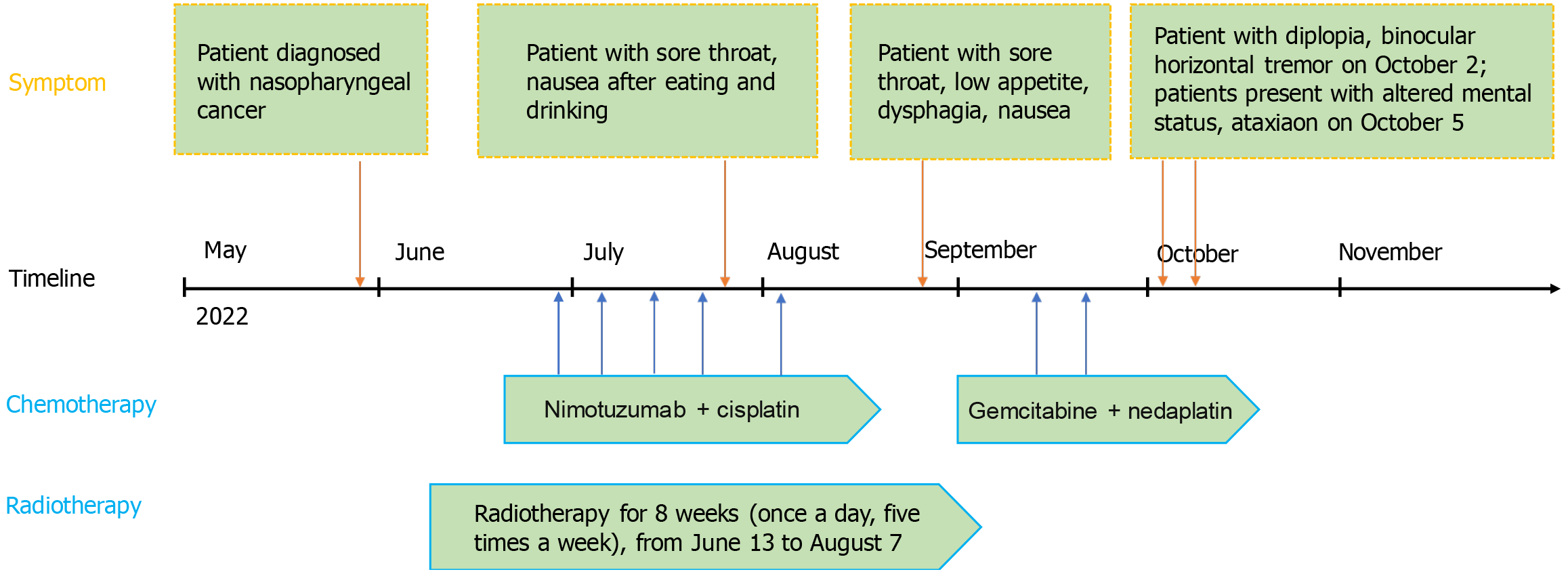

A young male patient with NPC, after undergoing four months of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, exhibited symptoms of altered mental status, impaired visual function, and gait ataxia (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Timeline of the case.

History of present illness

On May 28, 2022, a 33-year-old young male sought treatment at Shaanxi Provincial People’s Hospital for right ear fullness, right nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea with bloody discharge. After admission, a cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed on May 31, 2022, indicated a mass on the right posterior superior wall of the nasopharynx, suggestive of a tumorous change, likely NPC, with bilateral cervical lymph node metastasis. A pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of non-keratinizing undifferentiated NPC on the right side with bilateral cervical lymph node metastasis (T2N2M0 stage III). Immunohistochemical results were as follows: CK3(+), P63(+), KI-67 index approximately 80% (+), some residual FDC networks seen with CD21, partial positivity for CD56-CD20, positivity for CD interzone(+), and EGFR3(+). In situ hybridization showed EBV-encoded RNA epithelial cells (+). With reference to the guidelines[10], we performed image-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy on this patient. The patient began definitive chemoradiotherapy for NPC on June 13, 2022, with doses of PGTVnx (GTVnx + external 3 mm): 7260 cGy/33 f, PGTVnd: 6600 cGy/33 f, PTV1: 6006 cGy/33 f, PTV2: 5445 cGy/33 f, all within the range for endangered organs. The last radiotherapy session was administered on August 7. Additionally, the patient started concurrent chemotherapy and targeted therapy on June 28, with doses of nimotuzumab 200 mg and cisplatin 80 mg/m2 once a week for five weeks, with the last cycle on August 5. Apart from chemotherapy, treatments to prevent side effects of concurrent chemoradiotherapy included suppressing gastric acid secretion, antiemetics, maintaining electrolyte balance, and parenteral nutrition support (compound amino acid injection 18AA-VII, water-soluble vitamin injection, 20% fat emulsion injection C8-24Ve, potassium chloride injection, vitamin B6 injection, vitamin C injection). On July 23, the patient developed symptoms of sore throat and nausea after eating. Upon examination, his pharynx was found to be congested with scattered ulcers and hemorrhagic spots. Subsequently, he received symptomatic treatment with compound chlorhexidine gargle, topical recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor, and traditional Chinese medicine preparations, but the symptoms did not completely resolve. On August 24, the patient again experienced a sore throat accompanied by itching and swallowing difficulties. Additionally, he frequently felt low appetite, nausea, and even vomiting. An electronic laryngoscopy confirmed the diagnosis of radiation laryngitis, an expected common side effect of head and neck radiotherapy. Clinicians treated him with Kangfuxin solution and changed the chemotherapy regimen on September 13 to gemcitabine 1600 mg/m2 + nedaplatin 60 mg/m2 based on his symptoms. There were two cycles of this chemotherapy phase, with the last on September 20. However, there was no significant relief. Starting September 29, the patient began to experience intermittent runny nose with yellow discharge, intermittent vomiting, and nausea. On the morning of October 2, the patient developed diplopia, horizontal nystagmus of both eyes, incomplete abducens nerve palsy of the right eye, and visual fatigue. He received treatment to alleviate visual fatigue. On October 5, the patient exhibited positional limb tremors, ataxic gait, unclear speech, and intermittent irritability.

History of past illness

The patient was in good health.

Personal and family history

Patient had no history of alcohol abuse, smoking, or allergies. His personal, marital, and family histories were unremarkable.

Physical examination

The patient’s laboratory data were as follows: Temperature, 37.3 °C; pulse, 64 beats/minute (normal range: 60-100 beats/minute); blood pressure, 115/68 mmHg; respiratory rate, 21 breaths/minute; height, 184 cm; and weight, 63 kg [compared with the weight recorded on May 28 (96 kg), the patient’s weight decreased by 33 kg]. The patient was alert and oriented [physical examination on admission (September 29)].

Laboratory examinations

Routine blood tests were immediately conducted, and the hematological parameters were as follows: White blood cell count, 5.73 × 109/L; neutrophil ratio, 0.891 (normal range: 0.4-0.75); lymphocyte ratio, 0.03 (normal range: 0.2-0.5); eosinophil ratio, 0.003 (normal range: 0.004-0.08); absolute lymphocyte count, 0.2 × 109/L [normal range: (1.1-3.2) × 109/L]; red blood cell count, 2.87 × 1012/L (normal range: 4.35.8 × 1012/L); hemoglobin, 90 g/L (normal range: 130-175 g/L); red cell distribution width, 0.15 (normal range: 0.116-0.146); hematocrit, 0.258 (normal range: 0.4-0.5); plateletcrit, 0.15 (normal range: 0.19-0.36). Serum liver function biochemical results were as follows: Cholinesterase, 3754 U/L (normal range: 5000-12000); total protein, 63.6 g/L (normal range: 65-85); albumin, 36.6 g/L (normal range: 40-55). Serum kidney function biochemical results were as follows: Potassium, 3.1 mmol/L (normal range: 3.5-5.5); sodium, 135 mmol/L (normal range: 137-147); chloride, 89 mmol/L (normal range: 96-108); magnesium, 0.62 mmol/L (normal range: 0.75-1.02); retinol-binding protein, 22.4 mg/L (normal range: 25-70 mg/L); cystatin-c, 1.050 mg/L (normal range: 0.59-1.030 mg/L). Serum thyroid function biochemical results were as follows: Free triiodothyronine, 2.5 pmol/L (normal range: 3.5-7.0 pmol/L); anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies, 114.36 IU/mL (normal range: < 30 IU/mL). Serum anemia panel results were as follows: Vitamin B12, > 7344 pg/mL (normal range: 197-771 pg/mL); ferritin, 7760 ng/mL (normal range: 30-400 ng/mL) (laboratory tests on October 5).

Imaging examinations

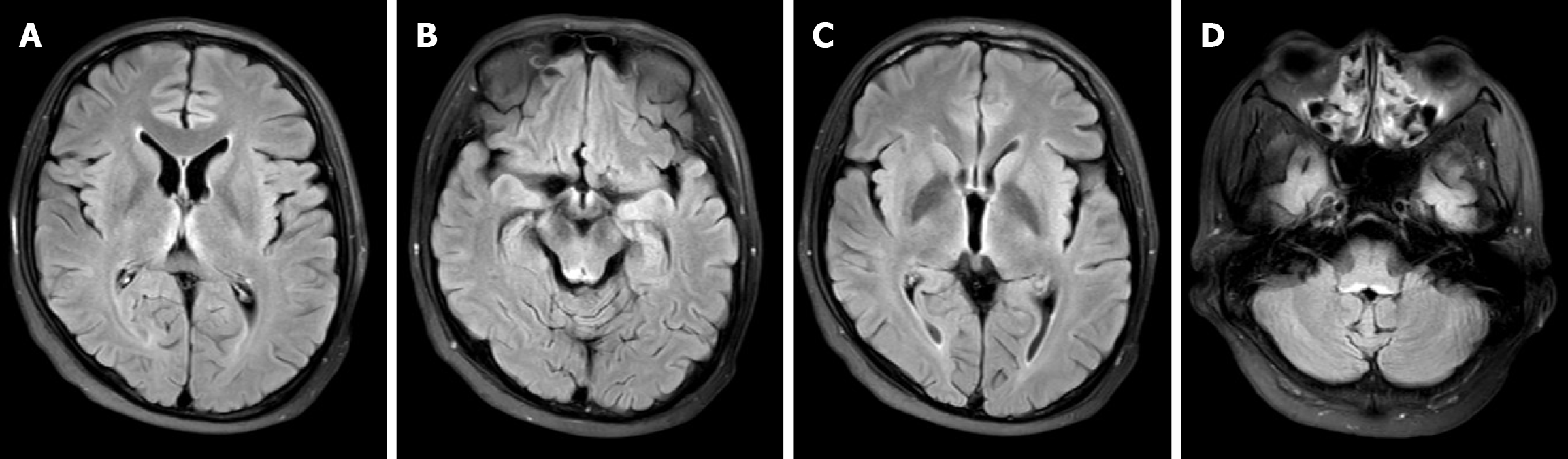

Cranial MRI revealed symmetric patchy slightly prolonged T1 and T2 signal intensities bilaterally within the medial thalami, mammillary bodies, and surrounding the third and fourth ventricles, with slightly increased signal on FLAIR and DWI sequences, and ill-defined margins; the imaging diagnosis was symmetric patchy abnormal signal intensities around the third and fourth ventricles and in the medial thalami and mammillary bodies, consistent with WE (MRI on October 5) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

A: Bilateral symmetrical hyperintense signals on T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) around the medial thalamus; B: Bilateral symmetrical hyperintense signals on T2WI and FLAIR around the mammillary bodies; C: Bilateral symmetrical hyperintense signals on T2WI and FLAIR around the third ventricle; D: Bilateral symmetrical hyperintense signals on T2WI and FLAIR around the fourth ventricle.

TREATMENT

After a neurology consultation, he was treated with thiamine injections 200 mg twice daily intramuscularly and enteral nutrition suspension 100 mL three times daily via nasogastric feeding. Considering the patient’s medical history and imaging results, clinicians diagnosed WE, which was unrelated to his physical condition before admission but considered associated with thiamine deficiency during concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The diagnosis is based on four main aspects. Firstly, the observed reduction in dietary intake and nutritional imbalance following chemotherapy and radiotherapy were noted. Secondly, the patient exhibited three typical clinical manifestations of Wernicke encephalopathy: Ocular dysfunction, altered mental status, and gait ataxia. Additionally, the characteristic imaging features of Wernicke encephalopathy were confirmed through MRI examination. Lastly, significant alleviation of neurological symptoms was achieved after thiamine treatment. Before confirming the diagnosis, we excluded other potential diseases. Adverse reactions to radiotherapy and chemotherapy were the first factors we considered, such as common side effects in the treatment of NPC including thrombocytopenia, anemia, granulocytopenia, mucositis, dry mouth, dysphagia, loss of appetite, vomiting, nausea, weight loss, liver and kidney function damage, peripheral neuropathy, and temporal lobe damage[11]. Although these symptoms could explain some of the patient’s clinical manifestations, they could not explain their MRI results. We also considered other diseases with similar MRI presentations as the patient, such as metronidazole encephalopathy and bilateral thalamic symmetric lesions (e.g., top of the basilar syndrome, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, epidemic encephalitis B, etc.)[12], but the medical history and clinical features of these diseases did not match this case. Five days after starting thiamine treatment, the patient’s mental state improved, which can be reflected by the accompanying symptoms of fatigue were significantly alleviated. After two weeks, the duration of symptoms such as diplopia and ocular tremor shows a declining trend. However, he continued to experience irritability and tremor after sitting up. Following the neurology consultation, he received an increased thiamine dosage, with injections of 300 mg twice daily and oral thiamine tablets of 100 mg three times daily. A week later, he transitioned to oral thiamine tablets 100 mg three times daily and was discharged.

DISCUSSION

WE is a neurological disorder caused by a deficiency in thiamine. Typically, thiamine must undergo several transport steps before it can function in brain cell metabolism. Thiamine ingested by the body is converted to its free form by intestinal phosphatases before entering enterocytes and then transferred across the intestinal epithelial cell membrane into the blood as thiamine pyrophosphate[13]. Thiamine in the blood exists in various forms, including free thiamine, three thiamine phosphates (monophosphate, diphosphate, and triphosphate), and adenosine thiamine triphosphate, among which thiamine diphosphate best reflects the body’s thiamine reserve levels and is also the bioactive form of thiamine. Thiamine diphosphate is an essential coenzyme in several key biochemical pathways in the brain, primarily involved in aerobic glucose metabolism, the production and maintenance of myelin, and processes such as amino acid and glucose-derived neurotransmitters (such as glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid), etc[14]. A deficiency in thiamine leads to reduced metabolic activity of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and pentose phosphate pathway in specific neuronal and astroglial cells in the brain, subsequently causing intracellular lactate accumulation, decreased pH, and localized acidosis in specific areas of the brain. These changes in cellular energy metabolism also cause mitochondrial dysfunction and intracellular oxidative stress, leading to astroglial cell dysfunction, such as promoting increased extracellular glutamate concentrations and disrupting the permeability of the blood-brain barrier[15]. The combined effect of these factors primarily causes disruption of the osmotic gradient across the cell membrane, cytotoxic edema, and these changes may be irreversible.

Computed tomography has limited value in identifying acute changes of Wernicke encephalopathy and is not the preferred imaging modality because, in most cases, it fails to identify the acute phase changes of Wernicke encephalopathy[16]. MRI of the brain can effectively display cytotoxic edema. Brain MRI shows that the medial thalami, perithird ventricular regions, periaqueductal areas, mammillary bodies, and the tectum of the midbrain are the areas most commonly affected by thiamine deficiency, manifesting as symmetrical T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities in the respective areas[17]. These regions are particularly sensitive to thiamine deficiency due to high rates of thiamine-related glucose and oxidative metabolism. Atypical MRI findings of Wernicke encephalopathy include symmetrical changes in the cerebellum, vermis, and cranial nerve nuclei[18], which are often associated with typical presentations. The European Federation of Neurological Societies guidelines indicate that MRI has a sensitivity of 53% and a specificity of 93% for diagnosing Wernicke encephalopathy[19]; therefore, a negative MRI does not rule out the diagnosis. In cases where clinical suspicion exists but MRI is negative, contrast-enhanced MRI can identify areas of blood-brain barrier disruption, reducing the incidence of false-negative MRI results[12]. However, imaging evidence alone cannot accurately identify Wernicke encephalopathy and must be combined with other aspects for a comprehensive diagnosis. Beyond imaging modalities, assessment of thiamine levels can also aid in diagnosis. Compared to direct measurement of free thiamine, its metabolite thiamine diphosphate more accurately reflects true thiamine levels. Additionally, analysis of erythrocyte transketolase activity by assessing changes in erythrocyte transketolase activity after adding exogenous thiamine pyrophosphate can diagnose thiamine deficiency. However, due to the lack of standardization of these assays[20], their practical application may be difficult to implement widely. Serum thiamine level testing is a common clinical method, but the concentration of thiamine in the blood does not necessarily reflect the concentration in brain tissue; thus, its value lies only in identifying suspected patients[21]. In terms of recognizing WE, medical and personal histories are important considerations that cannot be overlooked. The most common cause of thiamine deficiency is chronic alcoholism, but the possibility of Wernicke encephalopathy should also be considered in situations involving poor nutritional absorption and long-term parenteral nutrition support.

A multicenter observational study in Spain showed that non-alcoholic causative factors accounted for only 7% of the risk factors for Wernicke encephalopathy[22], which is similar to the analysis results of a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Switzerland[23]. Through the classification of risk factors in 4393 cases of Wernicke encephalopathy obtained from this study, we can find that patients with non-alcohol-related Wernicke encephalopathy account for 6.7% of all patients with Wernicke encephalopathy. Both studies suggest that the number of non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy patients is small, but considering that the sample source of such studies is hospitalized patients with a clear diagnosis and the fact that Wernicke encephalopathy is currently underdiagnosed[1], these studies may overlook those unidentified non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy patients. Therefore, the current clinical cases of non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy are few, which is not a reason to neglect the disease. Existing research and case reports show that, in addition to alcoholism, a variety of factors can lead to Wernicke encephalopathy, including bariatric surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, malignant tumors, refeeding syndrome, dialysis status, thyrotoxicosis, inflammatory bowel disease, anorexia nervosa, sequelae of coronavirus disease 2019, etc[14,24-26]. Identifying these risk factors helps in screening for Wernicke encephalopathy. The screening and diagnosis of Wernicke encephalopathy are still primarily clinical diagnoses, and paying attention to the risk factors of the disease helps to keenly identify situations affecting thiamine intake. According to the guidelines of the European Federation of Neurological Societies[19], after considering the characteristic of reduced thiamine absorption, patients only need to meet two of the typical triad of features of Wernicke encephalopathy to be clinically diagnosed with Wernicke encephalopathy, which undoubtedly reduces the false-negative results of clinical diagnosis.

In a systematic review of 586 cases of non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy[27], researchers found that the causative factors of non-alcoholic Wernicke encephalopathy attributed to malignant tumors accounted for 22%, and among these, 76% of patients had hematologic or gastrointestinal malignancies. A similar view can be drawn from another systematic review[28], which is that Wernicke encephalopathy caused by malignant tumors occupies a smaller proportion in the studied population, with NPC being even less common. Considering the current lack of epidemiological studies on Wernicke encephalopathy, although these two studies have publication bias and detection bias, they indicate that we must pay attention to the possibility of Wernicke encephalopathy occurring in cancer populations.

Currently, there is a paucity of research on the phenomenon of Wernicke encephalopathy in patients with malignant tumors. Existing studies suggest that the high metabolic characteristics of malignant tumors may promote the consumption of thiamine, which could be the cause of thiamine deficiency, commonly seen in hematologic malignancies[28]. Past case reports indicate that surgery or reduced intake in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies are potential factors precipitating Wernicke encephalopathy[29-31]. However, for NPC, there are currently no distinct features suggesting a potential correlation with the occurrence of Wernicke encephalopathy. In a randomized controlled trial using fedratinib to treat myelofibrosis, researchers found that four patients receiving fedratinib developed Wernicke encephalopathy[32] and another patient with lung cancer undergoing treatment with nivolumab developed Wernicke encephalopathy during therapy[33]. This could potentially suggest that certain therapeutic agents for malignant tumors might be potential precipitating factors for Wernicke encephalopathy; however, more cases are needed to support this view.

Early diagnosis of Wernicke encephalopathy and prompt administration of thiamine are crucial to preventing the progression to Korsakoff syndrome. Korsakoff syndrome, characterized by severe anterograde and retrograde amnesia, is caused by unrecognized or insufficiently treated Wernicke encephalopathy[34], and currently, there is no fully validated pharmacological treatment[35]. Compared to Wernicke encephalopathy, the chronic phase, namely Korsakoff syndrome, clinically presents with abnormal mental states, and disproportionate impairment of episodic memory function relative to other cognitive functions affected[36]. Neuropathological studies suggest that damage to the anterior nuclei of the thalamus also differs from the pathological changes in Wernicke encephalopathy; a study by NSWTRC demonstrates that damage to the tissue of the anterior nuclei of the thalamus is a key lesion leading to the severe memory impairment in Korsakoff syndrome[37]. Research on the progression from Wernicke encephalopathy to Korsakoff syndrome remains insufficient, but inadequate treatment is a plausible explanation for disease progression.

In animal experiments, there are conflicting views on the effect of additional thiamine supplementation on malignant tumors. Some studies indicate that extra thiamine increases the incidence of bladder cancer in rats and can inhibit the cytotoxicity of methotrexate; on the other hand, MDA231 breast cancer xenografts show delayed proliferation in mice on a thiamine-free diet[38]. Such studies demonstrate the dual characteristics of thiamine in both inhibiting and promoting cancer development, which may be related to different types of cancer or genetic factors, and more research is needed to support these viewpoints. However, preventive interventions for populations at risk of Wernicke encephalopathy have gained more recognition. Some scholars, considering the high risk of thiamine deficiency after bariatric surgery, suggest early screening and postoperative supplementation to prevent Wernicke encephalopathy[39]. Similarly, the European Federation of Neurological Societies guidelines recommend parenteral thiamine supplementation after bariatric surgery[19]. Nevertheless, a real-world study exploring the appropriate dosage of preventive thiamine supplementation in populations at risk of Wernicke encephalopathy found no significant difference in any cognitive outcome measures across different doses[40]. This suggests that we need to uncover more evidence to verify the reliability of preventive interventions.