Published online Aug 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i24.5583

Revised: June 4, 2024

Accepted: June 24, 2024

Published online: August 26, 2024

Processing time: 197 Days and 21.3 Hours

Endometrial cancer is a kind of well-known tumors of female genitourinary sys

We present three cases of endometrial carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion with cancer-free uterine cavity. One patient, a reproductive-aged woman, exhi

Cervical stromal invasion is easily missed if no cancer is found in the uterine body on MRI. Immunohistochemistry of endoscopic curettage specimens should be conducted to avoid underestimation of the disease.

Core Tip: We focus on endometrial carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion, given its correlation with reduced 5-year survival rates and heightened lymph node metastasis risk in patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer. Patients with cervical stromal invasion are required to have a total hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy. In contrast, they only require a total hysterectomy. In instances of endometrial carcinoma that involves the cervix but lacks an apparent primary uterine body tumor, magnetic resonance imaging examinations should be performed with greater caution to prevent potential misdiagnoses.

- Citation: Liu MM, Liang YT, Jin EH. Endometrial carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(24): 5583-5588

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i24/5583.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i24.5583

Endometrial cancer is known as a malignant tumor, and predominantly occurs women aged over 50 years, with a proportion of cases (4%) occurring in individuals under 40 years[1]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is important for preoperative evaluation of endometrial cancer, which can accurately evaluate prognostic indicators, and this information can aid clinicians in devising tailored treatment strategies[2,3]. The discovery of cervical stromal invasion by MRI may have many challenges, including difficulty in identifying the boundary between cervix and uterine body, and difficulty in distinguishing between cervical stroma and mucosa infiltration[4]. Nonetheless, an accurate evaluation of cervical stromal involvement is crucial for determining accurate staging, prognosis, and the necessity for adjuvant therapy. We report the results in the context of clinical practice that endometrial cancer involving cervical stroma without obvious lesions in the uterine cavity, and highlight what contribution this study adds to the literature already existing on the topic and to future study perspectives.

Case 1: A 48-year-old female patient had been experiencing intermittent vaginal bleeding for five years.

Case 2: A 44-year-old female patient experienced irregular menstruation for one year.

Case 3: A 64-year-old female patient had persistent abnormal vaginal bleeding for 10 days.

Case 1: Six years after menopause, the patient experienced five years of intermittent vaginal bleeding without abdominal pain and fever. Ultrasound examination indicated a thickened endometrium.

Case 2: This patient of childbearing age, with regular menstruation, and no dysmenorrhea, in the previous year, her period was advanced by seven days, with a large amount of blood accompanied by clots.

Case 3: This patient who had been postmenopausal for 20 years, presented with vaginal bleeding that was initially observed eight years previously and had not been treated. The vaginal bleeding recurred ten days ago.

Case 1 and 2: No previous health conditions.

Case 3: This patient had a 1 year history of diabetes, and used 6-9 U subcutaneous insulin and took 0.5 g metformin orally three times daily. The fasting blood glucose was controlled at 6.1-6.9 mmol/L.

All three patients did not have a history of smoking or alcohol abuse. They were no family history of the disease.

The vulva in these patients was normal. The vaginal mucosa exhibited smoothness, and the surface of the cervical region was also smooth. No masses were palpated in the pelvis, and no tenderness was detected within the pelvic cavity.

Human papilloma virus, thinprep cytologic test were normal in all patients.

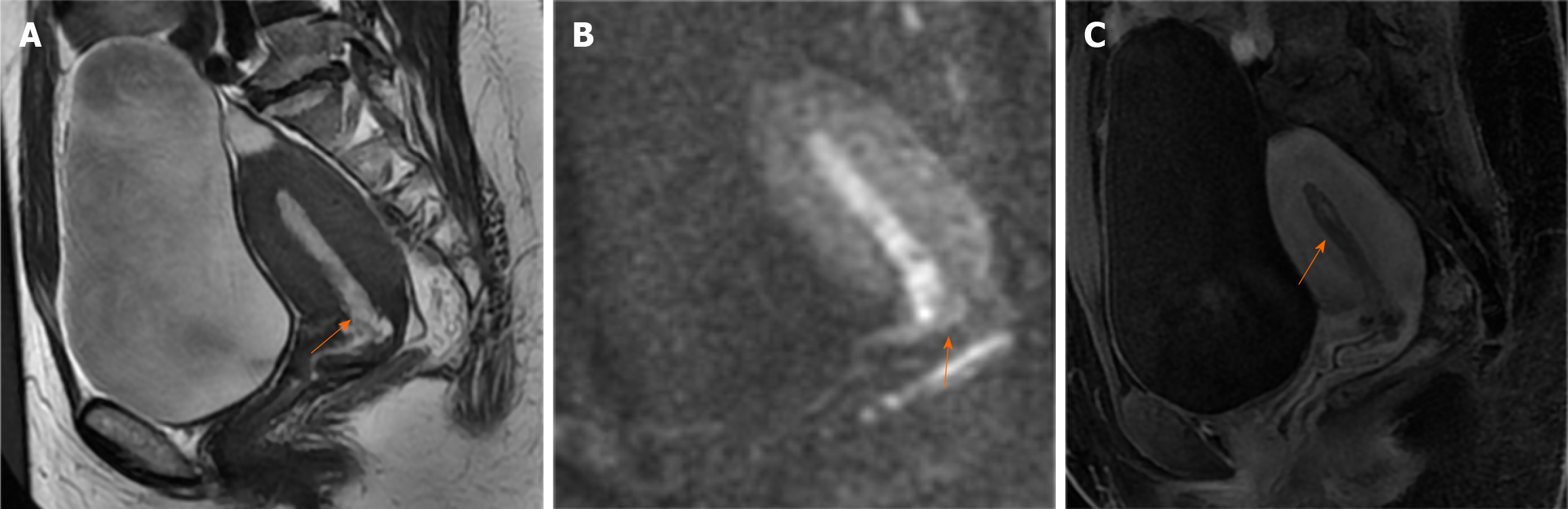

Case 1: Ultrasonography revealed that the endometrium was approximately 1.0 cm thick. Hysteroscopy indicated atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium. MRI (Figure 1) demonstrated an endometrium of similar thickness, with slightly elevated signals in both T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (Figure 1A) and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 1B) images. Enhanced scans (Figure 1C) revealed uneven enhancement of the endometrium, clearly demarcated from the muscle layer. Multiple small cysts were observed in the upper segment of the cervix, arranged in clusters.

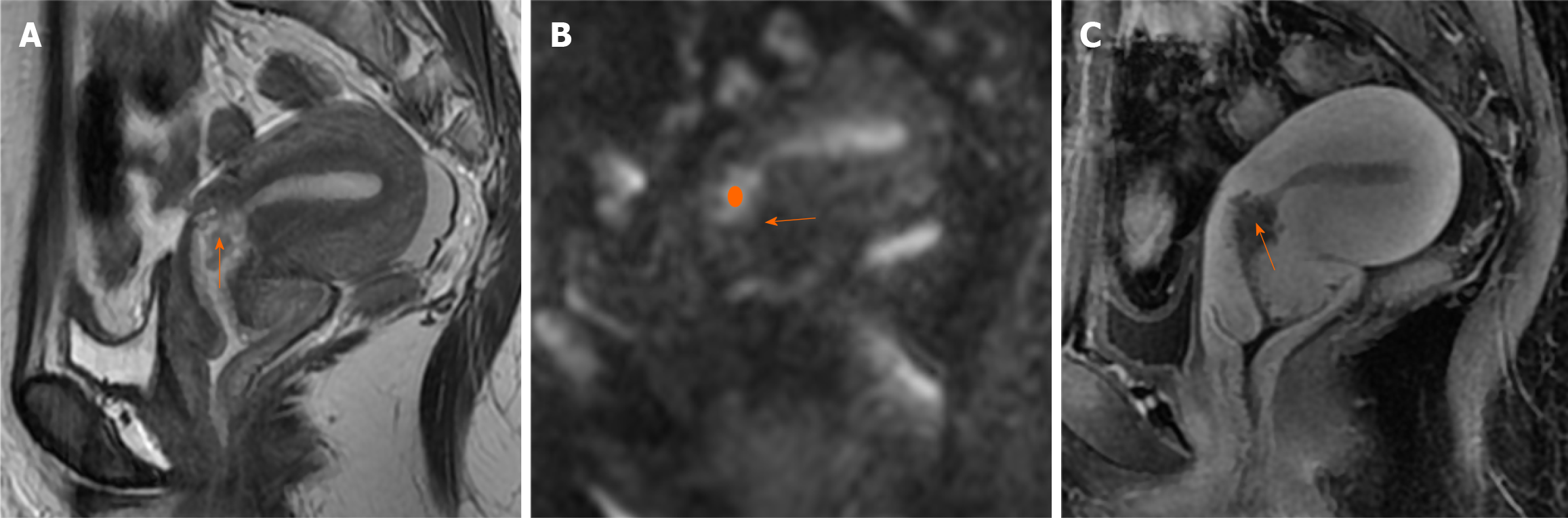

Case 2: Ultrasonography revealed that the endometrium was approximately 1.2 cm thick, with a distinct 1.8 cm polypoid nodule detected in the cervical canal. MRI examination indicated an endometrial thickness of 0.8 cm without obvious abnormalities. Nodules were identified within the isthmus of the uterus (Figure 2), extending into the cervical canal, with a diameter of 1.8 cm, which were considered to be endometrial polyps. The signal and enhancement characteristics of the endometrial polyps were similar to those of the endometrium.

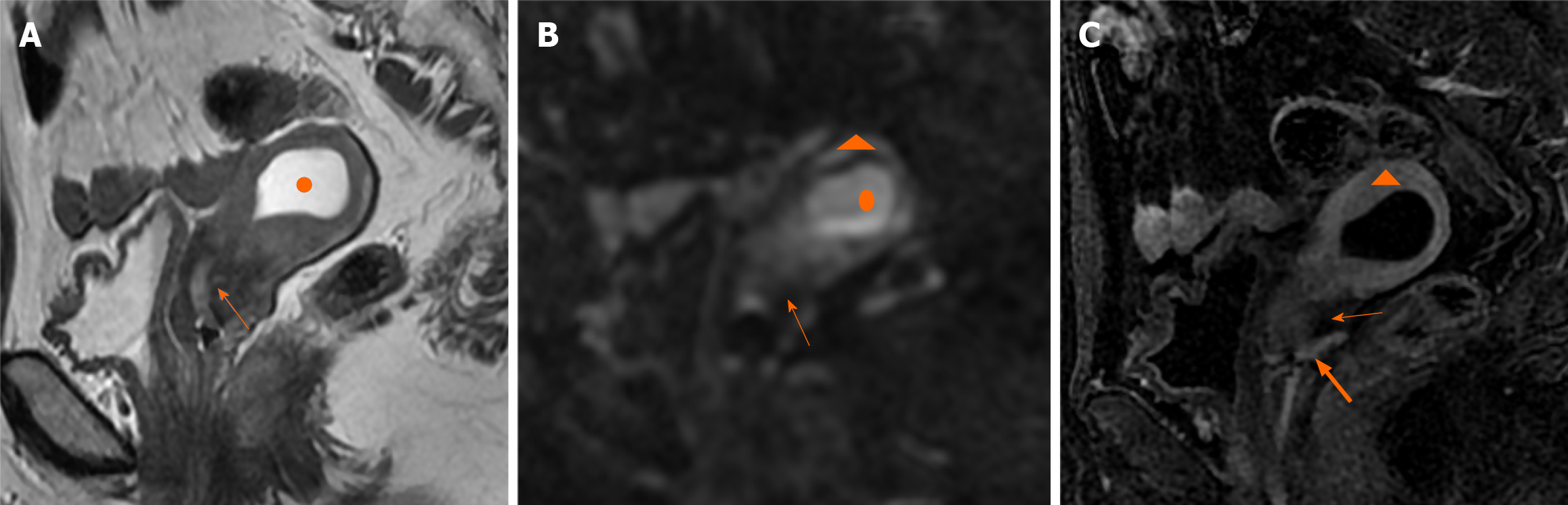

Case 3: Ultrasonography indicated that the endometrium was approximately 0.4 cm thick. MRI findings revealed hydrops of the uterus. The endometrium was thin (Figure 3). Uterine effusion showed a high signal on T2WI (Figure 3A), higher signal on DWI (Figure 3B), but no enhancement (Figure 3C). Additionally, uneven signals were observed in the myometrium and upper region of the cervix, which were attributed to compression of the hydrops in the uterus.

Renal-type adenocarcinoma in the endometrium, with cancerous tissue infiltrating less than 1/2 of the myometrium and down into the intercervical stroma (less than 1/2 wall thickness). The median renal-type adenocarcinoma involved both sides of the ovarian surface.

Uterine sub-endometrial polyps, adenocarcinoma alterations, high-moderate differentiation, and infiltration of the myometrium at a depth less than half of the myometrial thickness. Additionally, the cancer foci were situated within the superficial layer of the cervix.

Endometrial cancer Type II, serous carcinoma, focal clear cell carcinoma, invasive to the myometrium greater than 1/2 wall thickness, with visible vascular tumor thrombus, involving the cervical stroma (about 1/2 wall thickness).

The patient was treated by total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and para-aortic lymph node dissection. Postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy were performed.

The patient was treated by total hysterectomy, followed by postoperative radiotherapy.

The patient was treated by total hysterectomy, followed by postoperative radiochemotherapy.

Surgery was performed approximately one and a half years prior to the present study. Postoperative bleeding following intercourse occurred. Pathological examination of the vaginal endoscopic biopsy suggested chronic inflammation of the mucosal tissue.

At three years and two months post-surgery, there was no evidence of recurrence.

No recurrence was observed after a period of 2 years and 9 months.

Endometrial carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion is associated with lymph node metastasis and poor survival[5]. Lymph node status is a key prognostic indicator of endometrial cancer, and sentinel lymph node localization can even detect micrometastases and change the patient's treatment regimen[6]. Therefore, correct diagnosis of cervical interstitial involvement is crucial. Currently, MRI is the best imaging tool for evaluation of endometrial cancer.

At present, the standard for cervical stromal invasion by MRI is as follows[7]: On T2WI, a medium-intensity tumor disrupts the low signal intensity of the cervical stroma; on contrast-enhanced imaging, a low-intensity tumor disrupts the normal enhancement of the cervical stroma; and on DWI, a high-intensity tumor disrupts the low-intensity cervical stroma. There are primarily two patterns of endometrial carcinoma invading the cervix[8,9]: The first involves the tumor infiltrating the uterine body and both the cervix mucosa and cervical stroma, while the second involves the tumor directly penetrating the cervical stroma through the myometrium, bypassing the cervix mucosa. Cases of endometrial carcinoma involving the cervical stroma without a distinct lesion in the endometrial cavity are rare, and their pathogenesis remain unclear.

In our cases, hysteroscopy and segmental curettage suggested atypical hyperplasia and polyps in the endometrium. MRI examination in Case 1 revealed a heterogeneous endometrium, with thickened endometrium extending downward to the endocervix. No malignant tumors were detected within the endometrium. Multiple cysts were observed on the surface of the cervix mucosa, but the stroma remained intact; thus, endometrial hyperplasia was diagnosed. MRI examinations of Case 2 revealed a nodule in the endocervix, with no evidence of invasion into the cervical stroma. Case 3 presented with hydrosalpinx and a non-thickened endometrium. The myometrium exhibited inconsistent enhancement, which was interpreted as a consequence of compression of the muscle layer. No lesions were found in the cervix. All three patients had either missed or misdiagnosed MRI results.

Similar to the findings in the present study, Taylor et al[10] reported four patients with endometrial hyperplasia ex

Further assessment of Case 1 and Case 2, showed that their disease may be similar to the first type of invasion[8,9], where endometrial lesions (either polyps or hyperplasia) extending to the cervix, subsequently lead to secondary malignancy. These lesions then infiltrate into both the cervix mucosa and stroma, which is similar to the implantation invasion reported by Tambouret et al[11]. Case 3, may be identical to the second type of invasion, where cancer cells infiltrate the myometrium and then directly infiltrate the cervical stroma without accumulating in the cervical mucosa[8,9].

We describe a rare occurrence of endometrial carcinoma with cervical stromal invasion which presents a diagnostic challenge. When the criteria for endometrial carcinoma are not met, cervical stromal invasion may be present. We hope that our cases will enrich the diagnostic experience of radiologists, and help future research to discover the mechanism of this type disease. Furthermore, we advocate that clinicians should incorporate immunohistochemical results into routine hysteroscopy pathology assessments for a more comprehensive evaluation. This approach aims to prevent potential misdiagnoses and ensure appropriate treatment.

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21327] [Article Influence: 2132.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Rockall AG, Qureshi M, Papadopoulou I, Saso S, Butterfield N, Thomassin-Naggara I, Farthing A, Smith JR, Bharwani N. Role of Imaging in Fertility-sparing Treatment of Gynecologic Malignancies. Radiographics. 2016;36:2214-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lakhman Y, Akin O, Park KJ, Sarasohn DM, Zheng J, Goldman DA, Sohn MJ, Moskowitz CS, Sonoda Y, Hricak H, Abu-Rustum NR. Stage IB1 cervical cancer: role of preoperative MR imaging in selection of patients for fertility-sparing radical trachelectomy. Radiology. 2013;269:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toprak S, Sahin EA, Sahin H, Tohma YA, Yilmaz E, Meydanli MM. Risk factors for cervical stromal involvement in endometrioid-type endometrial cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;153:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bi Q, Chen Y, Chen J, Zhang H, Lei Y, Yang J, Zhang Y, Bi G. Predictive value of T2-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI for assessing cervical invasion in patients with endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Imaging. 2021;78:206-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bogani G, Giannini A, Vizza E, Di Donato V, Raspagliesi F. Sentinel node mapping in endometrial cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2024;35:e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sbarra M, Lupinelli M, Brook OR, Venkatesan AM, Nougaret S. Imaging of Endometrial Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2023;61:609-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bi Q, Bi G, Wang J, Zhang J, Li H, Gong X, Ren L, Wu K. Diagnostic Accuracy of MRI for Detecting Cervical Invasion in Patients with Endometrial Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. J Cancer. 2021;12:754-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McCluggage WG, Hirschowitz L, Wilson GE, Oliva E, Soslow RA, Zaino RJ. Significant variation in the assessment of cervical involvement in endometrial carcinoma: an interobserver variation study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:289-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Taylor J, McCluggage WG. Cervical stromal involvement by endometrial 'hyperplasia': a previously unreported phenomenon with recommendations to report as stage II endometrial carcinoma. Pathology. 2021;53:568-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tambouret R, Clement PB, Young RH. Endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma with a deceptive pattern of spread to the uterine cervix: a manifestation of stage IIb endometrial carcinoma liable to be misinterpreted as an independent carcinoma or a benign lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |