Published online Aug 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5416

Revised: May 20, 2024

Accepted: June 11, 2024

Published online: August 16, 2024

Processing time: 85 Days and 7 Hours

Endobronchial metastases (EBMs) are tumours that metastasise from a malignant tumour outside the lungs to the central and subsegmental bronchi, and are visible under a bronchofibrescope. Most EBMs are formed by direct invasion or metast

A 71-year-old male patient who had undergone radical left nephrectomy 7 years prior due to RCCC was referred to our hospital due to a 1-mo history of produc

EBM from RCCC has a low incidence and no characteristic clinical manifestations in the early stage. If a bronchial tumour is found in a patient with RCCC, the possibility of bronchial metastatic cancer should be considered.

Core Tip: Endobronchial metastases (EBMs) are tumours that metastasise from a malignant tumour outside the lungs to the central and subsegmental bronchi, and are visible under a bronchofibrescope. Renal clear cell carcinoma (RCCC) is a common malignant tumour of the urinary system. EBM from RCCC has a low complication rate and is often misdiagnosed as primary lung cancer. We report a case of post-operative EBM in a patient with RCCC who underwent laparoscopic radical nephrectomy 7 years ago. This suggested that if a bronchial tumour is found in a patient with RCCC, the possibility of EBM should be considered.

- Citation: Xie TH, Fu Y, Ha SN, Meng QX, Sun Q, Wang P. Endobronchial metastasis secondary to renal clear cell carcinoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(23): 5416-5421

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i23/5416.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5416

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC), comprising 2% to 3% of all tumours, is a common malignant neoplasm affecting the urinary system[1,2]. Renal clear cell carcinoma (RCCC), being the most prevalent pathological type of RCC, comprises approximately 70% to 80% of all RCC cases and is most frequently observed in individuals aged 50 years to 70 years. RCC can spread and metastasise through arterial, venous and lymphatic circulation to almost all organs of the body. Moreover, lung, bone, liver, brain and local recurrence are the most common metastatic neoplasms of RCC[3]. Most extrathoracic malignancies that metastasise to the lung are RCCs, but endobronchial metastasis (EBM) from RCCC has a low incidence rate[4]. Herein, we report a case of post-operative bronchial metastasis in a patient with RCCC who underwent laparoscopic radical nephrectomy 7 years ago.

A 71-year-old male patient with a 1-mo history of productive cough was referred to our outpatient department for further evaluation.

Symptoms started 1-mo before presentation with recurrent productive cough. A soft tissue nodule in the upper lobe of the left lung was detected by a chest computed tomography (CT) scan, prompting hospitalisation for additional evaluation.

The patient underwent laparoscopic radical resection of the left kidney 7 years ago, and post-operative pathology indicated that the grade II RCCC invaded the renal fibrous fascia, and no cancerous tissue was found in the vessels of the broken ureter or the renal portal. Post-operative recovery was successful, and Ubenimex was taken orally to enhance immunity. The patient was not re-examined after discharge.

The patient had no history of smoking, drinking, or recent travel. His medical and family history did not reveal any significant health issues.

During the physical examination, both lung areas exhibited normal breathing sounds. The abdomen was soft, painless, and did not reveal any palpable masses.

Laboratory examinations, including routine blood, renal function, urine, and stool tests, as well as evaluations of tumour markers (carbohydrate antigen [CA] 125, CA15-3, CA19-9, CA72-4, carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha fetoprotein), did not indicate any abnormalities.

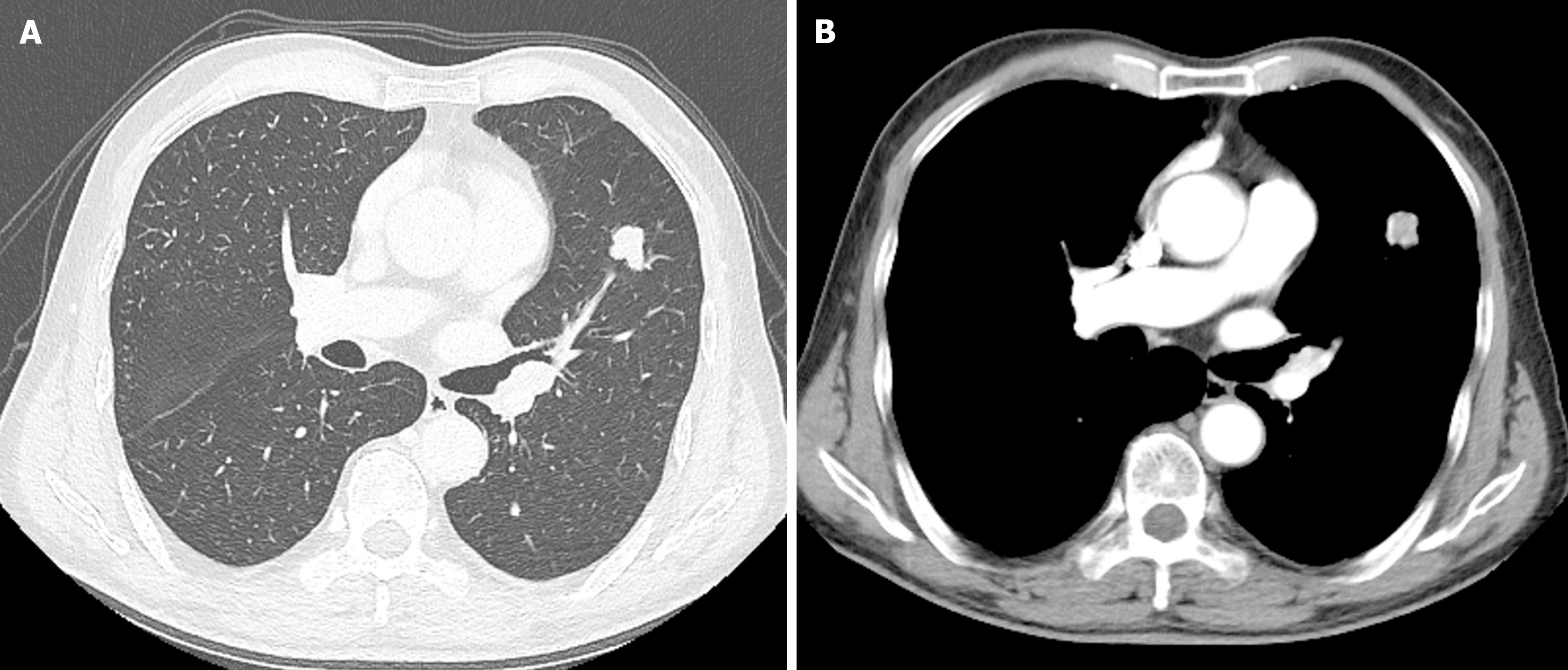

The results of an enhanced chest CT scan indicated the presence of a soft tissue nodule in the upper lobe of the left lung, suggesting a high likelihood of peripheral lung cancer (Figure 1). Abdominal enhanced CT showed no signs of tumour recurrence or metastasis. A whole-body bone scan revealed no abnormalities.

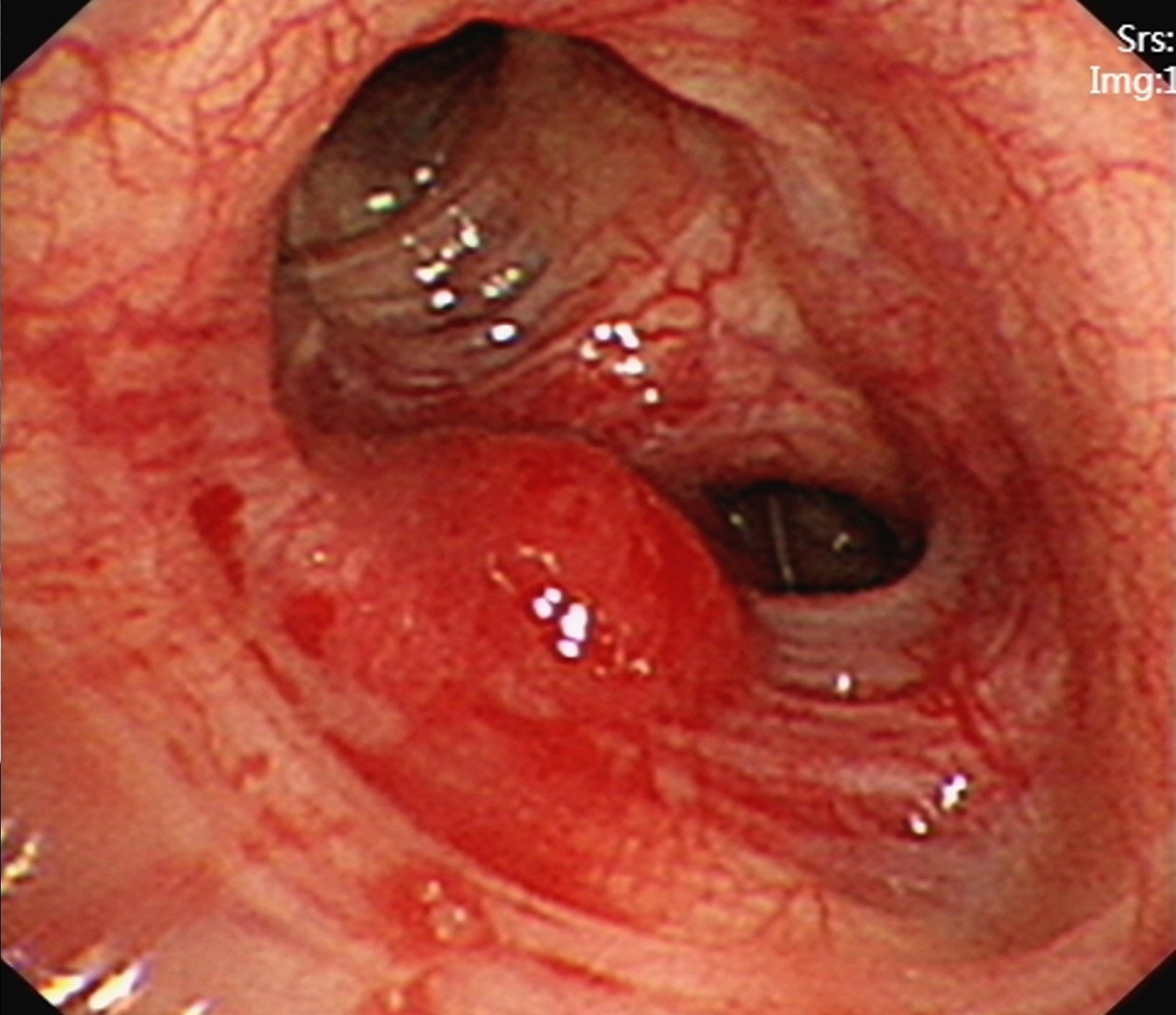

Subsequently, a hypervascular lesion was detected in the bronchus of the left lung superior lobe by flexible bronchoscopy (Figure 2). However, pathology revealed no tumour cells by bronchial brushing.

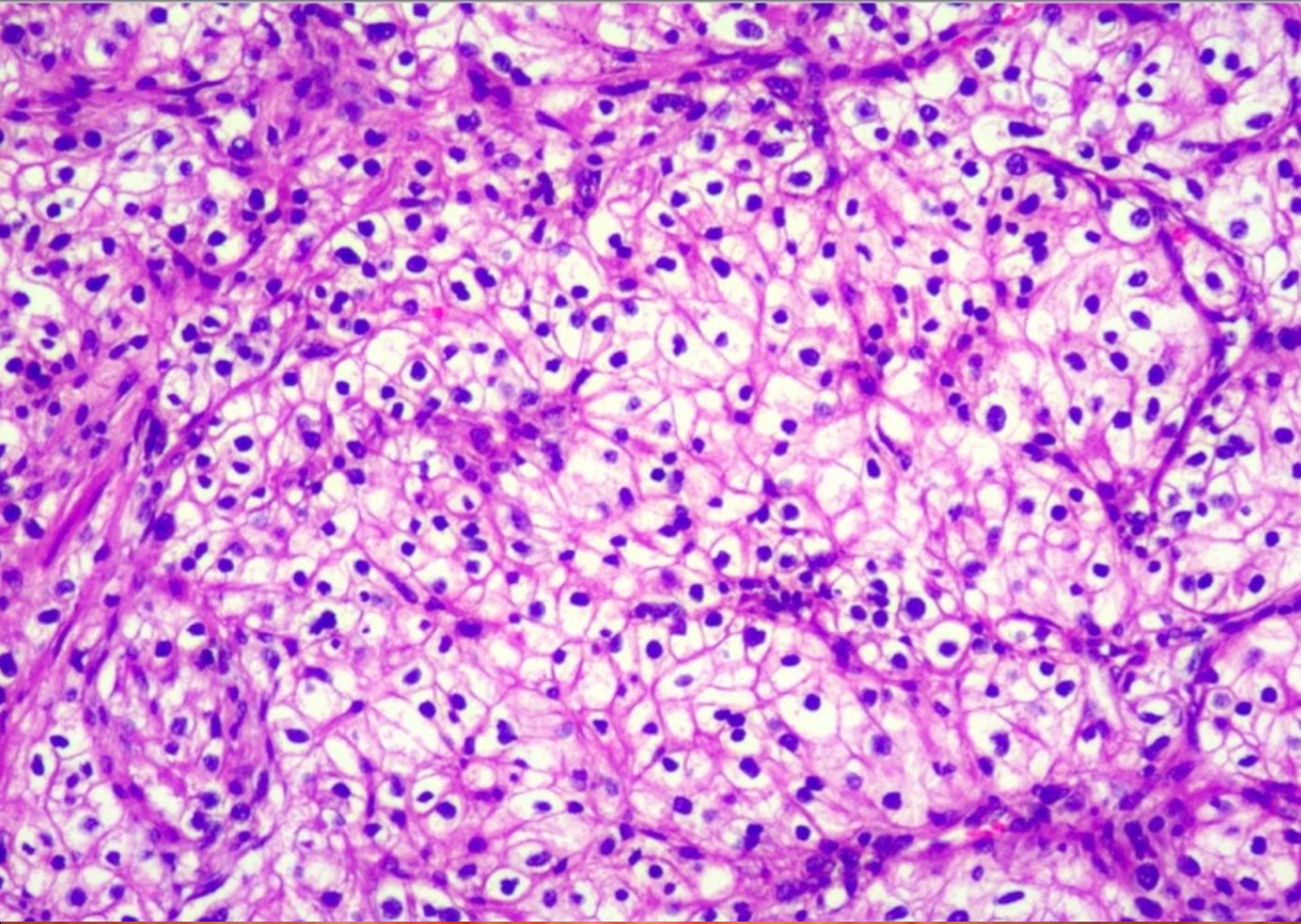

Pathological examination revealed clear cell carcinoma with a maximum diameter of approximately 2.2 cm, which did not invade the visceral pleura (Figure 3). No cancer was found at the incision margin of the suture nail. Combined with the immunohistochemical results and medical history, these findings were consistent with the origin of the kidney. Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for CD10, CAX and CK, but negativity for Melan-A, HMB-45, S-100 and CK7. The patient was diagnosed with RCCC with EBM based on the detailed microscopic findings and radiological correlation (stage IV: T1N0M1).

After consultation, the patient underwent surgery, and thoracoscopic left superior lobe wedge resection was performed under general anaesthesia.

The patient recovered smoothly without severe complications, and refused radiotherapy, chemotherapy or targeted therapy. There was no recurrence or metastasis found by CT at the 6-mo follow-up.

EBM is a tumour that metastasises from a malignant tumour outside the lungs to the central and subsegmental bronchi and is visible under a bronchofibrescope[5]. Most EBMs are formed by direct invasion or metastasis of intrathoracic malignant tumours, such as lung cancer, oesophageal cancer or mediastinum tumours. In 4% of cases where bronchoscopy is performed for suspected malignancy, extrapulmonary tumours are detected through endobronchial mucosal biopsy, and approximately 5% of these cases present with metastasis as the initial sign of the neoplasm[6]. The diagnostic modalities for EBM include CT, bronchoscopic biopsy, bronchial brushing, endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration, surgical biopsy, X-ray and bronchoalveolar lavage.

Kiryu et al[5] divided EBMs into four types based on the invasion mode: Type I, direct metastasis to the airway; Type II, invasion of the airway through parenchymal lesions of the lung; Type III, mediastinal or hilar lymph node metastasis invading the airway; and Type IV, peripheral lesions growing along the proximal bronchus.

RCCC is characterised by insidious onset, high malignancy and rapid progression. Early-stage RCCC is generally asymptomatic and difficult to detect. Approximately 20%-30% of patients have metastasis at the initial diagnosis[7], and nearly 30% of patients experience recurrence and metastasis after surgery[8].

The CT imaging findings of RCCCs with lung metastasis are varied and include the following: (1) Intrapulmonary metastasis, typically characterised by single or multiple round soft tissue density nodules in the lung with clear boundaries and uniform density, which are easy to diagnose; and (2) EBM, manifested as bronchial obstruction and truncation, possibly resulting in obstructive pneumonia and atelectasis, which is rare and is often misdiagnosed as primary lung cancer. In this case, the EBM, characterised by a soft tissue density shadow and lobulated segmentation, originating from the RCCC, was located in the bronchial branch of the upper lobe of the left lung. The lesion was characterised by soft tissue density shadows and lobed segmentation. An enhanced scan revealed uneven enhancement, and the patient was misdiagnosed with peripheral lung cancer.

It has been reported that for tumours with characteristic CT findings of EMB from RCCC growth in the bronchus along the bronchial wall, bronchial tube diameter thickening resembles a glove-finger appearance. The degree of enhancement in the cortical period is significantly enhanced, and the degree of strengthening in the parenchymal period is rapidly reduced, showing a “fast-in and fast-out” phenotype[9]. Unfortunately, there were no such characteristic CT findings in this patient.

Although bronchoscopic biopsy is regarded as the most effective diagnostic tool for patients with EBM, its diagnostic accuracy in assessing EBM is comparatively low, stemming primarily from the high rate of false-negative results associated with this method[5]. In this case, bronchoscopy provided evidence of EBM, although the pathology results from the bronchial brush biopsy were negative.

The symptoms of EBM most frequently manifest as coughing and haemoptysis, subsequently accompanied by dyspnoea and wheezing[10,11]. Although these symptoms may also occur in patients with respiratory diseases, any of these symptoms in patients with extrapulmonary tumours may indicate the possibility of EBM. In addition, the proportion of asymptomatic patients is still 52%-62.5%[5,12,13]. At this time, regular chest CT and bronchoscopy after the onset of symptoms are necessary. Pathological examination and immunohistochemistry are used for the diagnosis of EBM.

Post-operative follow-up is an important part of the treatment process of RCCCs, the main purpose of which is to detect any tumour recurrence, metastasis or new tumour formation in a timely manner, in addition to monitor the preservation of renal function after surgery. The follow-up process typically involves three stages:

Early follow-up: This occurs within 1 to 2 wk after surgery. The focus is on assessing wound healing, determining the next steps of the treatment plan, and evaluating post-operative recovery and any complications. During this stage, the doctor may recommend necessary tests based on the patient’s specific condition, such as blood tests (complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, electrolyte levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and chest X-rays.

Intermediate follow-up: This occurs at 4 to 6 wk after surgery. It involves repeat blood tests, as well as additional imaging tests such as chest CT scans if abnormalities are detected on chest X-rays. Abdominal ultrasounds may also be performed, and if abnormalities are found or if the patient underwent partial nephrectomy or has advanced-stage RCCC (T3-T4), abdominal CT scans may be recommended. These scans may be repeated every 6 mo for 2 years, and the frequency may be adjusted based on the patient’s condition.

Long-term follow-up: For patients with early-stage RCCC, follow-up visits are typically scheduled at intervals of 3 mo to 6 mo for the initial 3 years, and then annually thereafter. However, for those with advanced-stage RCCC, the follow-up schedule is more intensive, with visits every 3 mo for the first 2 years, followed by every 6 mo in the third year, and annually afterwards. During these visits, the doctor may recommend additional tests such as magnetic resonance imaging scans of the central nervous system or urine catecholamine testing, depending on the patient’s specific condition and treatment.

EBM from RCCC has a low incidence and lacks characteristic clinical manifestations in the early stage compared to that of primary lung cancer. For this type of atypical lung metastatic cancer, it is difficult to make an accurate diagnosis solely based on imaging examination, and comprehensive judgement should be made by combining medical history, physical signs, laboratory tests and other auxiliary examinations. The diagnosis ultimately depends on pathological examination and immunohistochemistry. If a bronchial tumour is found in a patient with RCCC, the possibility of bronchial metastatic cancer should be considered.

| 1. | Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, Alva A, Baine M, Beckermann K, Carlo MI, Choueiri TK, Costello BA, Derweesh IH, Desai A, Ged Y, George S, Gore JL, Haas N, Hancock SL, Kapur P, Kyriakopoulos C, Lam ET, Lara PN, Lau C, Lewis B, Madoff DC, Manley B, Michaelson MD, Mortazavi A, Nandagopal L, Plimack ER, Ponsky L, Ramalingam S, Shuch B, Smith ZL, Sosman J, Dwyer MA, Gurski LA, Motter A. Kidney Cancer, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:71-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 130.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 64542] [Article Influence: 16135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (176)] |

| 3. | Stephenson AJ, Chetner MP, Rourke K, Gleave ME, Signaevsky M, Palmer B, Kuan J, Brock GB, Tanguay S. Guidelines for the surveillance of localized renal cell carcinoma based on the patterns of relapse after nephrectomy. J Urol. 2004;172:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Doğan D, Turan D, Özgül MA, Çetinkaya E. The role of interventional pulmonology in endobronchial metastasis of renal cell carcinoma. Tuberk Toraks. 2019;67:211-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kiryu T, Hoshi H, Matsui E, Iwata H, Kokubo M, Shimokawa K, Kawaguchi S. Endotracheal/endobronchial metastases : clinicopathologic study with special reference to developmental modes. Chest. 2001;119:768-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marchioni A, Lasagni A, Busca A, Cavazza A, Agostini L, Migaldi M, Corradini P, Rossi G. Endobronchial metastasis: an epidemiologic and clinicopathologic study of 174 consecutive cases. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:222-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bukowski RM. Natural history and therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the role of interleukin-2. Cancer. 1997;80:1198-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney cancer (v. 1. 2024) [EB/OL]. (2023-05-12) [2023-11-10]. Available from: https://www.nccnchina.org.cn/guide/detail/406. |

| 9. | Park CM, Goo JM, Choi HJ, Choi SH, Eo H, Im JG. Endobronchial metastasis from renal cell carcinoma: CT findings in four patients. Eur J Radiol. 2004;51:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salud A, Porcel JM, Rovirosa A, Bellmunt J. Endobronchial metastatic disease: analysis of 32 cases. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62:249-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Akoglu S, Uçan ES, Celik G, Sener G, Sevinç C, Kilinç O, Itil O. Endobronchial metastases from extrathoracic malignancies. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:587-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Heitmiller RF, Marasco WJ, Hruban RH, Marsh BR. Endobronchial metastasis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;106:537-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Poe RH, Ortiz C, Israel RH, Marin MG, Qazi R, Dale RC, Greenblatt DG. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of bronchoscopy in neoplasm metastatic to lung. Chest. 1985;88:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |