Published online Aug 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5404

Revised: May 10, 2024

Accepted: June 13, 2024

Published online: August 16, 2024

Processing time: 87 Days and 20.6 Hours

With the incidence of pancreatic diseases increasing year by year, pancreatic hyperglycemia, as one of the common complications, is gradually gaining atten

This was the case of an elderly female with clinical manifestations of necrolytic migratory erythema, “three more and one less,” diabetes mellitus, hypertension, anemia, hypoproteinemia, and other syndromes, which had been misdiagnosed as eczema. Abdominal computed tomography showed a pancreatic caudal space-occupying lesion, and the magnetic resonance scanning of the epigastric region with dynamic enhancement and diffusion-weighted imaging suggested a tumor of the pancreatic tail, which was considered to be a neuroendocrine tumor or cystadenoma. The patient was referred to a more equipped hospital for laparoscopic pancreatic tail resection. Post-surgery diagnosis revealed a neuroendocrine tumor in the tail of the pancreas. To date, the patient’s general condition is good, and she is still under close follow-up.

Necrolytic migratory erythema can be induced by endocrine system tumors or endocrine metabolic abnormalities, with complex clinical manifestations, difficult diagnosis, and easy misdiagnosis by dermatologists. The initial treatment prin

Core Tip: This report presented a case of necrolytic migratory erythema, a rare skin condition triggered by pancreatic hyperglycemia. Here, we highlighted the diagnostic challenges, therapeutic strategies, and prognostic considerations in the management of this complex disease.

- Citation: Zhan SP. Necrolytic migratory erythema caused by pancreatic hyperglycemia with emphasis on therapeutic and prognosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(23): 5404-5409

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i23/5404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5404

The core presentation of necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) is intermittent episodes of erythema, plaques, and papules with hyperpigmentation, most often circumscribed[1]. It can be triggered by various diseases, such as enteropathic acral dermatitis, and skin disorders such as severe drug rash, pancreatic glucagonoma (GCGN), hepatitis B, and cholangiocarcinoma. NME is the first and specific skin lesion manifestation of GCGN (a tumor of pancreatic islet A cells), with an incidence of 68%-90%[2]. Both are known as GCGN syndrome, which is extremely rare clinically, with an incidence of about 1/2000000000 people[3]. Therefore, the pathophysiology of this disease is poorly understood, and misdiagnosis is frequent despite the specific symptoms of NME, perioral inflammation/linguitis, diabetes mellitus, and anemia.

Most patients diagnosed with GCGN having NME have distant metastases and poor prognosis, with a median survival of 3-7 years[4]. Therefore, it is crucial to enhance the clinical understanding of GCGN and NME, to screen and diagnose the disease at an early stage, to accept surgical treatment before distant metastasis, and to improve the prognosis of the patients. This study presents a case of GCGN with NME admitted to the Department of Dermatology of Wuhan Brain Hospital, Yangtze River Shipping General Hospital to elucidate the key points of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis and to deepen the understanding of this disease.

A 77-year-old female was admitted to the Department of Dermatology of our hospital on April 26, 2022 for erythema of the trunk and limbs and dandruff with itching for half a year.

Six months prior, the patient had migratory erythema with itching without any obvious triggers, which was concentrated in the lower limbs, buttocks, shoulders, back, waist, and abdomen but did not yet involve the face. It was initially characterized by irregular erythema, with some of the erythema bulging around to form a ring or a map and showed dark red pigmentation after scratching, ulceration, scabbing, and healing. She was administered topical medication (e.g., a medication to treat the skin) by local hospitals. She had been treated with topical medication (specific name and dosage unknown) in a local hospital for eczema. The rash was reduced, but the lesions were still recurring after discontinuation of the medication. Thus, she consulted the Department of Dermatology of our hospital.

The patient’s medical history revealed that she had hypertension for > 40 years that was controlled by oral antihypertensive drugs. She was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus 5 years prior to admission that was controlled by oral metformin, control. The admission diagnosis was eczema, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension grade 3 (very high risk).

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

Vital signs included: Temperature of 36.3 °C; pulse 90 beats/minute; respiration 19/minute; and blood pressure 113/78 mmHg. Physical examination revealed clear, automatic position, neck soft, jugular vein was not furious, the hepatic jugular venous reflux sign was negative, normal respiratory sounds of the lungs, no dry and wet rales, the heart boundary was not big, heart rhythm was neat, and no murmur. The abdomen was soft, the liver and spleen were not palpable under the ribs, there was no percussion pain in either kidney, and there was mildly depressed edema below both knees.

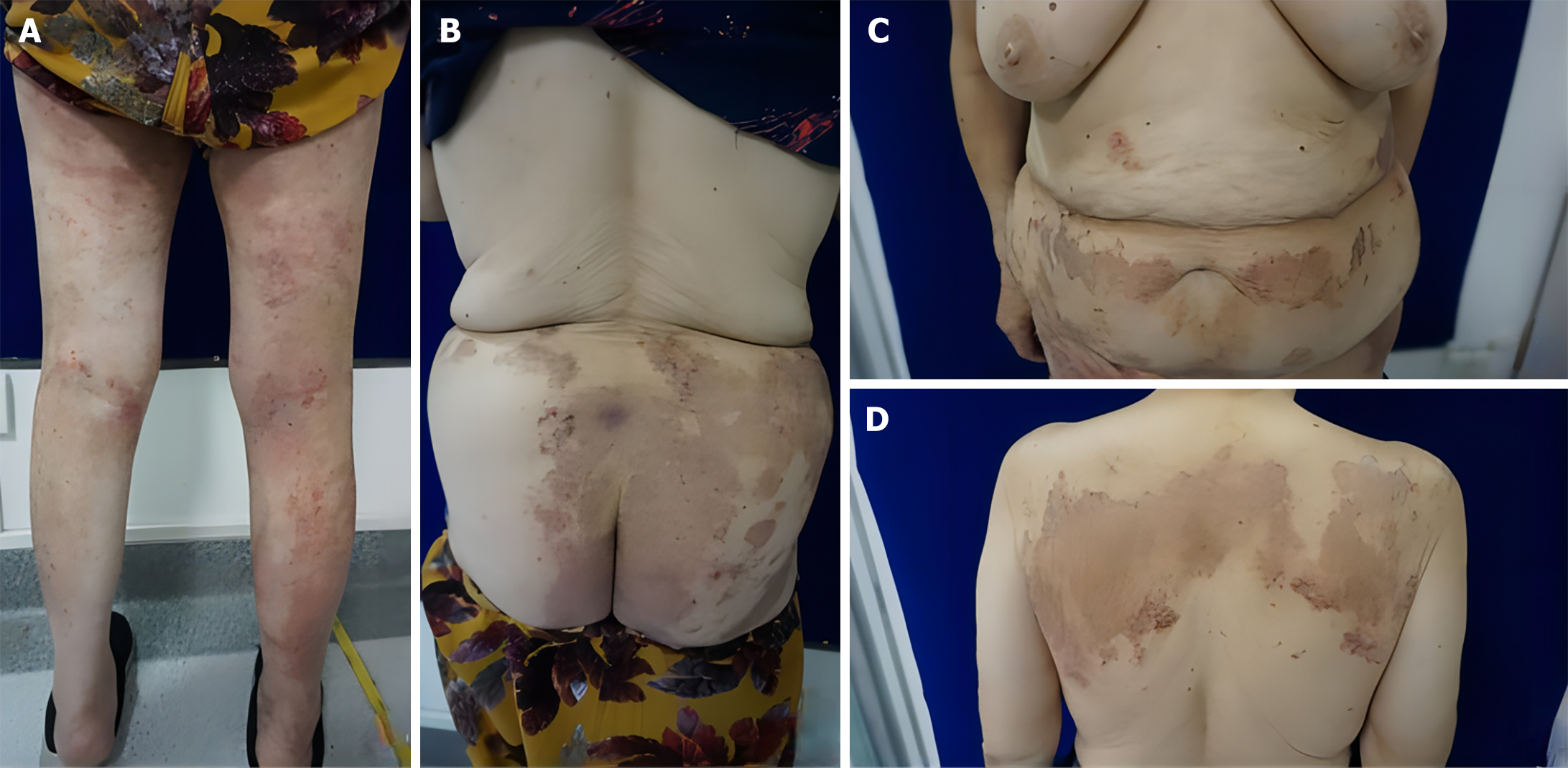

The back of the shoulders, waist and abdomen, buttocks, and limbs had large patches of dark erythema, in the form of rings and maps, raised around the erythema. They had clear boundaries, on which were scattered dander and dark red scabs. The lower limbs had erythema based on dense scratches and scabs, no obvious ulceration or oozing, no blisters, nodules, etc, and some of the erythema centers faded, leaving hyperpigmentation (Figure 1).

Random blood glucose was 9.9 mmol/L, and blood ketones were 0.1 mmol/L. Routine blood examination revealed: Lymphocyte percentage 15.70% (down); lymphocyte count 0.80 × 109/L (down); erythrocytes 3.17 × 1012/L (down); hemoglobin concentration 95 g/L (down); erythrocyte pressure 30.0% (down); and average hemoglobin concentration 315.00 g/L (down). The fasting blood glucose was 7.27 mmol/L (up). Diabetes test revealed: C-peptide 14.97 ng/mL (up); and serum insulin 108.40 μU/mL (up). Electrolytes were: Potassium 3.49 mmol/L (down). Lipid profile results were: Triglycerides 1.72 mmol/L (up); and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 0.83 mmol/L (down). The renal function profile showed: Uric acid 404 μmol/ L(up); and glomerular filtration rate 79 mL/min(down). Six liver functions were: Total protein 61.40 g/L (down); albumin 37.80 g/L (down); and aspartate aminotransferase 12.30 U/L (down). Coagulation function, an immunity three, heart attack three, glycated hemoglobin, and calcitonin showed no significant abnormalities. C-reactive protein was 18.4 mg/L (up), D-dimer was 1.53 mg/L (up), and B-type natriuretic peptide was 415.6 ρg/mL (up). Blood sedimentation and urinary and fecal routines revealed no significant abnormalities.

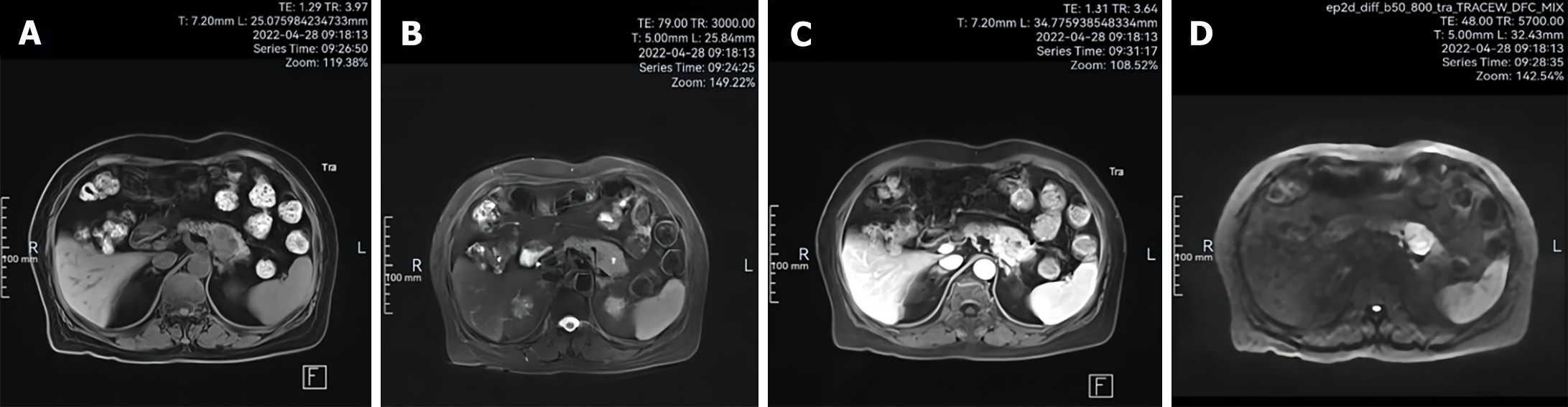

Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm and atrial premature beats. Chest computed tomography (CT) scanning revealed thickening of the tail of the pancreatic body and uneven density, leading to the possibility of pancreatic body tail occupancy. Fungal microscopy (buttocks, calves, and back dermatomes) were all negative. Epigastric magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with dynamic enhancement and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) revealed a pancreatic tail mass of low-signal T1WI, low T2WI iso-low mixed signals, of approximately 2.77 cm × 2.86 cm, having clear borders. The DWI was a high signal, and the apparent diffusion coefficient map was a low signal. Pancreatic tail tumor was visualized (Figure 2; possible neuroendocrine tumor or cystadenoma).

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was NME.

Antihistamine, antiallergic, and local physical therapy were administered during hospitalization. When the patient’s skin lesions improved significantly, she was discharged from the hospital and transferred to a higher-level hospital. Carbohydrate antigen 125 was 6.2 U/mL (normal value: 0.1-27.0 U/mL), and neuron-specific enolase was 14.63 μg/L (normal value: < 16.3 μg/L). Laparoscopic resection of the pancreatic tail lesion was performed after stabilization of the condition, and postoperative pancreatic pathology was performed. The macroscopic view revealed a pancreatic tissue of 10.8 cm × 5.5 cm × 2.7 cm, and there was a 3.5 cm × 3.5 cm × 2.7 cm pancreas 3.3 cm away from the cut edge of the pancreas. There was a 3.5 cm × 3.0 cm × 2.8 cm grayish-white mass in the pancreas, grayish-white on the cut surface, hard, and no lymph nodes were detected in the splenic hilum. Immunohistochemical staining showed tumor cells: PCK (+); CD56 (+); CgA (+); Syn (+); Ki67 (LI: 4%); β-Catenin (plasma +); BCL10 (-); and Chymotrypsin (-). This was consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor in the tail of the pancreatic body (NET, G2). One week postoperatively, the patient’s rash had largely subsided, and at 2 wk postoperatively, the patient’s glucagon level had decreased.

At present, the patient’s general condition is satisfactory, and she is under regular close follow-up.

NME was officially named by Wilkinson in 1973, initially as a specific skin lesion of GCGN. In 1979, Mallinson referred to GCGN and its associated series of syndromes (including NME, diabetes mellitus, anemia, and perioral inflammation/tongue inflammation) as GCGN syndrome. In this study, we reported a case of an elderly female who initially presented to our dermatology department with NME and was subsequently diagnosed with GCGN with NME.

We searched the relevant literature to summarize the key points of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of GCGN with NME as follows. The patient was admitted to the dermatology department of our hospital because of erythema on the trunk and limbs, which was concentrated on the lower limbs, buttocks, back of the shoulders, waist, and abdomen. It was initially characterized by irregular erythema, with the surrounding elevation in the form of a ring or a map, which was scratched, ulcerated, scabbed, and healed to show a dark reddish pigmentation. She also presented with typical diabetic manifestations such as dry mouth, polydipsia, polyuria, and weight loss.

Her medical history revealed type 2 diabetes mellitus for 5 years and hypertension for more than 40 years (grade 3, very high risk). According to the laboratory results, the erythrocyte pressure volume and erythrocytes were reduced, suggesting anemia. A hemoglobin concentration of 95 g/L suggests a mild degree of anemia, while an average hemoglobin concentration of < 320 g/L suggests small-cell hypopigmented anemia. The average hemoglobin concentration was < 320 g/L, suggesting microcytic hypopigmented anemia. This type of anemia has many causes, including cancer, iron deficiency, abnormal iron metabolism, chronic bleeding, and hemorrhoids. The appearance of skin lesions after anemia is clinically common.

A potassium level of 3.49 mmol/L suggests that the body is mildly hypokalemic, which is mainly related to decreased oral intake, increased release of total immunoreactive insulin, loss of potassium in the digestive tract, frequent vomiting and diarrhea, and loss of potassium in the urine. This reasons typically do not cause skin lesions. However, diabetes and diarrhea are secondary symptoms of GCGN, which cannot be excluded as a result of diabetes or diarrhea induced by GCGN.

Liver function, total protein, albumin, and aspartate aminotransferase decreased, suggesting hepatocellular damage or malnutrition. Common causes include malignant tumors, liver disease, renal disease, nutrition, and absorption disorders. Among them, albumin, as the main carrier of electrolytes and essential amino acids, will reduce the level of fatty acids, electrolytes, and other nutrient transfer, which will lead to the depletion of epidermal proteins and necrolysis and then NME.

In addition, it was also found that the patient had reduced renal function and inflammation, which may have led to the accumulation of waste, which can stimulate the skin to induce itchiness. The formation of NME and inflammation can lead to dysregulation of the immune system.

Moreover, the insulin and C-peptide release test suggested that the patient was in an early stage of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which was a non-insulin-dependent type. Her blood glucose could be effectively controlled by dietary interventions and the oral administration of metformin glucose-lowering drugs. However, because GCGN tumor cells independently secrete more glucagon to raise blood glucose, it further stimulated B cells to release insulin. Due to the antagonistic effect, the body’s blood glucose rise was not obvious, and it could have also manifested as early diabetes mellitus. Therefore, clinicians often misdiagnose GCGN as type 2 diabetes mellitus. According to the diagnostic criteria of GCGN agreed upon by several scholars in the past, we must focus on monitoring the glucagon level and consider the possibility of GCGN if it is > 1000 ng/L.

Further, imaging examinations are necessary to find the thickening and uneven density of the tail of the pancreatic body. In this case, further imaging examination was applied, and the thickening and uneven density of the tail of the pancreatic body was found in the chest CT scan. The possibility of pancreatic tail occupation was considered. Further improvement of the upper abdomen MRI with dynamic enhancement and DWI showed that the tail of the pancreatic body was a mass of T1WI low-signal and T2WI iso-low mixed signals. The size of the mass was about 2.77 cm × 2.86 cm, with poorly defined borders, and inhomogeneous enhancement, suggesting that it was a tumor of the tail of the pancreatic body, and a neuroendocrine tumor or cystadenoma should be considered.

Based on the clinical symptoms and medical history, physical and dermatological examinations, and laboratory and imaging evidence, a preliminary diagnosis of GCGN with NME was made at our hospital. Due to the limitations of the hospital, the patient was referred to a higher-level hospital to improve the examination after the symptomatic treatment of itching and rash symptoms was relieved to enable the patient to receive timely treatment.

The additional tumor marker test and positron emission tomography/MRI of growth inhibitory receptors were considered to be positive lesions of growth inhibitory receptors, and neuroendocrine neoplasia was considered to be a positive lesion of the neuroendocrine receptor. Receptor-positive lesions, the possibility of neuroendocrine tumors, and laparoscopic pancreatic tail lesion resection, according to the postoperative pancreatic histopathology confirmed the presence of a pancreatic mass. PCK (+), CD56 (+), CgA (+), and Syn (+) were used for immunohistochemistry. They are commonly used as markers for neuroendocrine tumors, of which CgA has the strongest specificity, and CD56 is the most sensitive but lacks specificity. The results confirmed a neuroendocrine tumor of the tail of the pancreatic body. This supports the accuracy of our initial diagnosis, combined with previous evidence in the literature[5-8].

In this article, there was a lack of dermatopathologic and glucagon test data. The diagnostic basis was slightly insufficient, and the diagnostic points of GCGN with NME were briefly described: (1) Clinical symptoms of GCGN with NME were relatively typical, including NME, diabetes mellitus, “three more and one less,” diarrhea, and perioral inflammation/tongue inflammation; (2) Medical history was accompanied by diabetes; (3) Routine blood tests, liver function, renal function, blood lipids, electrolytes, blood glucose and C-peptide release test, fasting glucagon and serum tumor markers were improved, and particular attention was paid to monitoring fasting glucagon levels; (4) Imaging examination was the primary method of preoperative diagnosis, using abdominal CT and MRI to show pancreatic mass as a reliable diagnostic basis, and growth inhibitor receptor positron emission tomography/MRI imaging were used under the condition. This provided information on the expression of growth inhibitor receptors and glucose transporter protein receptors in the primary and metastatic foci of neuroendocrine tumors, which can significantly improve the detection rate and accuracy of neuroendocrine tumors; and (5) The gold standards for the diagnosis of GCGN in NME are postoperative pancreatic histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

In this case, serum tumor markers were normal, and Ki67 (LI: 4%) was < 5%, which was of low grade. Combined with the characteristics of tumor cell heterogeneity and structure, the patient was diagnosed as having a neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreatic tail (NET, G2) according to the 2010 World Health Organization Neuroendocrine Tumor Grade Criteria. Currently, the patient has not yet developed distant metastases, and surgery was the first option to improve the prognosis. Our hospital did not have surgical conditions, so only symptomatic treatment was performed, including antihistamine, anti-allergy, and local physical therapy for the skin lesions and itching on the trunk and limbs.

The patient was transferred to a higher-level hospital when the skin lesions improved significantly because the lesion involved the spleen. Laparoscopic pancreatic tail resection and laparoscopic splenectomy were performed. Postoperatively, the patient developed a pancreatic fistula that was adequately drained, and no obvious peritoneal fluid was observed on repeat CT. Postoperatively, the patient’s blood potassium level was low; oral and intravenous potassium supplementation was provided. Albumin level improved, and enteral and parenteral nutritional support was provided.

Combined with previous evidence in the literature[9-12], the treatment and prognostic points of GCGN with NME were briefly summarized: (1) Preoperative application of growth inhibitory analogs such as octreotide helped to reduce patients’ glucagon levels and ameliorated skin lesion symptoms; (2) If erythema and rash were present on the abdomen that interfere with the surgical incision, an intravenous infusion of amino acids or oral zinc preparations were feasible to relieve the rash; (3) Postoperative hypoglycemic drugs were generally not required and should be administered in strict compliance with medical advice; (4) Molecularly targeted drugs have brought new hope for the treatment of metastatic GCGN. Sunitinib and everolimus have been certified by the United States Food and Drug Administration for use in the treatment of low and intermediate-grade metastatic GCGN but have not yet been introduced in China. Their exact efficacy has yet to be confirmed by more evidence-based research trials; and (5) Because this patient did not have distant metastasis, no postoperative chemotherapy was needed, but most patients have distant metastasis at the time of definitive diagnosis and need to be supplemented with necessary postoperative chemotherapy.

The main chemotherapeutic drugs are adriamycin, 5-fluorouracil, and azelnimidamide. Domestic experts generally believe that azemetidine is the most effective, with a recommended dose of 400 mg/day, a 5-d course of treatment once a month for a total of 3-10 courses of treatment. After discharge from the hospital, patients should improve their nutrition, pay attention to rest, and follow up regularly. Early diagnosis and surgery before the occurrence of distant metastases are essential to improve patient prognosis. Even if distant metastases are present preoperatively, aggressive surgery and comprehensive treatment are expected to achieve high long-term survival rates.

NME can be induced by endocrine tumors or endocrine metabolic abnormalities, and dermatologists are prone to misdiagnosis. The initial treatment principles in dermatology include symptomatic supportive therapy and effective drugs to relieve skin lesions. After clarifying the etiology of GCGN, comprehensive treatment in collaboration with endocrinologists, general surgeons, and oncologists can help provide individualized treatment and improve patient prognosis.

| 1. | Bosch-Amate X, Riera-Monroig J, Iranzo Fernández P. Glucagonoma-related necrolytic migratory erythema. Med Clin (Barc). 2020;155:418-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cui M, Wang R, Liao Q. Necrolytic migratory erythema: an important sign of glucagonoma. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97:199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dulcich G, Mestas Nuñez MA, Gentile EMJ. [Migratory necrolytic erythema as a manifestation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Clinical-radiological evaluation]. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba. 2022;79:188-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yacine O, Ksontini FL, Ben Mahmoud A, Magherbi H, Fterich SF, Kacem M. Case report of a recurrent resected glucagonoma. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;77:103604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Aragón-Miguel R, Prieto-Barrios M, Calleja-Algarra A, Pinilla-Martin B, Rodriguez-Peralto J, Ortiz-Romero P, Rivera-Diaz R. Image Gallery: Necrolytic migratory erythema associated with glucagonoma. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhu WF, Zheng SS. Glucagonoma syndrome with necrolytic migratory erythema as initial manifestation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2021;20:598-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tolliver S, Graham J, Kaffenberger BH. A review of cutaneous manifestations within glucagonoma syndrome: necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:642-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang ZX, Wang F, Zhao JG. Glucagonoma syndrome with severe erythematous rash: A rare case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e17158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wu SL, Bai JG, Xu J, Ma QY, Wu Z. Necrolytic migratory erythema as the first manifestation of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rodríguez G, Vargas E, Abaúnza C, Cáceres S. Necrolytic migratory erythema and pancreatic glucagonoma. Biomedica. 2016;36:176-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tseng HC, Liu CT, Ho JC, Lin SH. Necrolytic migratory erythema and glucagonoma rising from pancreatic head. Pancreatology. 2013;13:455-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Adam DN, Cohen PD, Ghazarian D. Necrolytic migratory erythema: case report and clinical review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:333-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |