Published online Aug 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5354

Revised: May 5, 2024

Accepted: June 14, 2024

Published online: August 16, 2024

Processing time: 131 Days and 9.2 Hours

Current concepts of beauty are increasingly subjective, influenced by the viewpoints of others. The aim of the study was to evaluate divergences in the perception of dental appearance and smile esthetics among patients, laypersons and dental practitioners. The study goals were to evaluate the influence of age, sex, education and dental specialty on the participants’ judgment and to identify the values of different esthetic criteria. Patients sample included 50 patients who responded to a dental appearance questionnaire (DAQ). Two frontal photographs were taken, one during a smile and one with retracted lips. Laypersons and dentists were asked to evaluate both photographs using a Linear Scale from (0-10), where 0 represent (absolutely unaesthetic) and 10 represent (absolutely aesthetic). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test analysis were measured for each group. Most patients in the sample expressed satisfaction with most aspects of their smiles and dental appearance. Among laypersons (including 488 participants), 47 pictures “with lips” out of 50 had higher mean aesthetic scores compared to pictures “without lips”. Among the dentist sample, 90 dentists’ perception towards the esthetic smile and dental appearance for photos “with lips” and “without lips” were the same for 23 out of 50 patients. Perception of smile aesthetics differed between patients, laypersons and dentists. Several factors can contribute to shape the perception of smile aesthetic.

To compare the perception of dental aesthetic among patients, laypersons, and professional dentists, to evaluate the impact of age, sex, educational background, and income on the judgments made by laypersons, to assess the variations in experience, specialty, age, and sex on professional dentists’ judgment, and to evaluate the role of lips, skin shade and tooth shade in different participants’ judgments.

Patients sample included 50 patients who responded to DAQ. Two frontal photographs were taken: one during a smile and one with retracted lips. Laypersons and dentists were asked to evaluate both photographs using a Linear Scale from (0-10), where 0 represent (absolutely unaesthetic) and 10 represent (absolutely aesthetic). One-way ANOVA and t-test analysis were measured for each group.

Most patients in the sample expressed satisfaction with most aspects of their smiles and dental appearance. Among laypersons (including 488 participants), 47 pictures “with lips” out of 50 had higher mean aesthetic scores compared to pictures “without lips”. Whereas among the dentist sample, 90 dentists’ perception towards the esthetic smile and dental appearance for photos “with lips” and “without lips” were the same for 23 out of 50 patients. Perception of smile aesthetics differed between patients, laypersons and dentists.

Several factors can contribute to shape the perception of smile aesthetic.

Core Tip: An aesthetically pleasing smile is not only dependent on elements such as tooth position, size, shape, and color, but also on the amount of gingiva exposed and lip positioning. All of these facial features are essential to achieve a harmonious form, emphasizing the importance of physical appearance and facial attractiveness. However, the concept of attractiveness varies between individuals influenced by uncontrollable factors such as cultural differences, as well as their personal and social background. Several studies have shown significant differences in aesthetic perception concerning various factors, including the presence of a black triangle, inflamed gingiva, diastema, malocclusion, midline shift, facial asymmetry, buccal corridor and gingival display. Many studies have reported significant differences on the aesthetic perception among laypersons and dentists. Although there is an existing body of research, a deeper comprehension of how dental appearances are perceived is required. Additionally, there are limited scientific data regarding the relationship between variations in skin color and tooth shade values in terms of perceived attractiveness. There was no widely recognized scientific relationship between skin color and smile perception. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare perception of dental aesthetic among patients, laypersons, and professional dentists.

- Citation: Aldegheishem A, Alfayadh HM, AlDossary M, Asaad S, Eldwakhly E, AL Refaei NAH, Alsenan D, Soliman M. Perception of dental appearance and aesthetic analysis among patients, laypersons and dentists. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(23): 5354-5365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i23/5354.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i23.5354

Over the past few years, there has been notable public awareness regarding dental treatment, emphasizing the importance of teeth in both function and facial aesthetics. During interpersonal communication, it is common for people to direct their attention toward the center of the face, which is the mouth, where the smile plays a crucial role in facial expression and enhancing one’s appearance[1].

An aesthetically pleasing smile is not only dependent on elements such as tooth position, size, shape, and color, but also on the amount of gingiva exposed and lip positioning[2]. All of these facial features are essential to achieve a harmonious form, emphasizing the importance of physical appearance and facial attractiveness.

However, the concept of attractiveness varies between individuals influenced by uncontrollable factors such as cultural differences, as well as their personal and social background[3]. Several studies have shown significant differences in aesthetic perception concerning various factors, including the presence of a black triangle, inflamed gingiva[1], diastema[5,6], malocclusion[6], midline shift[7], facial asymmetry, buccal corridor and gingival display[8,9]. Many studies have reported significant differences on the aesthetic perception among laypersons and dentists[7,10,11].

It is widely accepted that a trained and observant eye can easily distinguish the imbalances and disharmony within its environment[10]. Moreover, several studies have shown that the aesthetic perception of dental features is influenced not only by an individual’s level of education but also by other factors including sex, age and cultural background[1,12-15].

Although there is an existing body of research, a deeper comprehension of how dental appearances are perceived is required. Additionally, there are limited scientific data regarding the relationship between variations in skin color and tooth shade values in terms of perceived attractiveness[16]. There was no widely recognized scientific relationship between skin color and smile perception. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare perceptions of dental aesthetic among patients, laypersons, and professional dentists, as follows:

To evaluate the impact of age, sex, educational background, and income on the judgments made by laypersons.

To assess the variations in experience, specialty, age, and sex on professional dentists’ judgment.

To evaluate the role of lips, skin shade and tooth shade in different participants’ judgments.

The data collection phase was divided into three stages: (1) Dental photography and dental appearance questionnaire (DAQ) for participants; (2) Questionnaire for dentist; and (3) Questionnaire targeting laypersons.

This cross-sectional study received approval from the Deanship of Scientific Research, Princess Norah University under the study number 17-0183.

Fifty female patients aged between 18 years and 40 years were randomly selected from active patients treated in the dental clinic. Patients having orthodontic appliance or any aesthetic dental treatment such as veneers, full coverage crown or any aesthetic fillings were excluded from the study.

The participants were asked to answer DAQ (Table 1), which had been translated into Arabic. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were tested[17]. The questionnaire consists of 11 elements, and it was developed to assess the satisfaction of the participants. Furthermore, patients were asked about their history of orthodontic treatment or the use of lip fillers.

| Number | Question |

| Q1 | I am content with the appearance of my teeth |

| Q2 | I am content with the size of my teeth |

| Q3 | I am content with the shape of my teeth |

| Q4 | I am content with the color of my teeth |

| Q5 | I am content with the position of my teeth |

| Q6 | I am content with the appearance of my gum |

| Q7 | I tend to hide my teeth |

| Q8 | I wish I had other teeth |

| Q9 | I feel rather old because of my teeth |

| Q10 | I am dissatisfied with the black hole disease between my teeth. |

| Q11 | I am dissatisfied that my teeth are recognized as artificial |

(1) Measurement of length-width of central incisor, laterals and canines using digital caliper.

(2) Recording of skin shade based on Fitzpatrick scale (Figure 1)[18,19].

(3) Recording of teeth shade using digital shade detector (Ray Plicker, Borea, France), and the shade was validated by Vita classic shade guide (Figure 2).

and (4) Age of patient and level of education were also recorded.

The shade of each patient’s teeth was measured using the digital shade detector (Ray Plicker) scale (A1-D4), where (A1–A4) represents Reddish–Brownish tooth shade, (B1-B4) represents Reddish–Yellowish tooth shade, (C1-C4) represents Greyish tooth shade, and (D1-D4) represents Reddish Grey tooth shade. In addition to the shade categorization, tooth brightness was rated on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 representing the lightest and 4 representing the darkest tooth brightness.

Two frontal photographs were taken in compliance with standard dental photography (AACD) using a Nikon digital camera. The camera was positioned at a fixed angle of 90 degrees with adjustable height on camera holder. Participants were positioned at a distance of 22 inches from the camera, and their head position was stabilized using Facebow ear pieces in a vertical position connected to a stand perpendicular to the head (Figure 3). The first photograph was taken with the patient smiling to document the maximum number of teeth and gingiva displayed during laughing or broadly smiling. The second photograph was taken with retracted lips, and the same retractor was used to ensure standardization (Figure 4).

The tested criteria affecting aesthetic perception included golden proportion, recurrent esthetic dental proportion, width to height ratio, apparent contact dimension, upper lip position, upper lip curvature, parallelism of the maxillary anterior incisal curve with the lower lip (smile arc), relationship between the maxillary anterior teeth and the lower lip, number of maxillary teeth displayed in the smile, presence of diastema between the maxillary central incisors, smile arc/lower lip distance, upper lip height, lower lip height, midline discrepancy, lateral incisor edge position and skin and teeth shade on aesthetic perception.

The assessment of dental appearance was performed by laypersons, dentists representing various specialties, experiences, and sexes. They were requested to evaluate the dental appearance using standardized digital photographs. Additionally, laypersons, and dentists were requested to judge the photographs based on aesthetic appearance using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

Laypersons received training how to use (VAS) by being shown two photos of patients not included in the study. Once they felt comfortable with the process, they were asked to use the VAS to analyze the photos. The VAS was graded on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing absolutely unaesthetic and 10 representing absolutely aesthetic. Demographic information collected from dentists included sex, age, nationality, place of work, specialty, and years of experience. Laypersons were asked about their sex, age, educational level, and income.

The collected data were analyzed using Statistical Software SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics were calculated using parametric tests (t-test and one-way analysis of variance) as well as non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis). To assess the normality testing, Shapiro-Wilk test was used.

The results of this study are presented according to the following: patient sample characteristics, layperson sample characteristics, dentist sample characteristics, comparison among patients, laypersons and dentists’ perception, and the aesthetic analysis of patients’ photographs.

The patient sample included 50 female participants. Most of the patients were in the age group of 20 years to 29 years, with only 2 patients falling into the age group of 50 to 69. In terms of treatment, 62.0% of the patients underwent orthodontic treatment while 38.0% did not. Additionally, only 8.0% of the patients underwent filler treatment, while the 92.0% did not choose this option.

Regarding patient satisfaction, 66.0% of patients expressed satisfaction (satisfied/highly satisfied) regarding the size of their teeth, 42.0% of patients reported satisfaction (satisfied/highly satisfied) concerning the color of their teeth. 54.0% of patients were satisfied (satisfied/highly satisfied) with the appearance of their gum, whereas 30.0% of patients could not decide whether they are satisfied or not with the appearance of their gum (Table 2).

| Variable | Highly dissatisfied | Dissatisfied | Cannot decide/do not know | Satisfied | Highly satisfied | Total |

| Appearance of teeth | 9 (18.0) | 9 (18.0) | 19 (38.0) | 13 (26.0) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Size of teeth | 8 (16.0) | 9 (18.0) | 23 (46.0) | 10 (20.0) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Shape of teeth | 8 (16.0) | 10 (20.0) | 22 (44.0) | 10 (20.0) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Color of teeth | 2 (4.0) | 16 (32.0) | 11 (22.0) | 14 (28.0) | 7 (14.0) | 50 (100.0) |

| Position of teeth | 9 (18.0) | 8 (16.0) | 21 (42.0) | 12 (24.0) | 50 (100.0) | |

| Appearance of gum | 2 (4.0) | 6 (12.0) | 15 (30.0) | 16 (32.0) | 11 (22.0) | 50 (100.0) |

Assessments of patient's behavioral attitudes related to their dental appearance was performed on a five-point Likert scale where a score of 1 indicated “strongly disagree” and a score of 5 represented “strongly agree”. It was found that 74% of patients responded either “strongly disagree” or “disagree” regarding hiding their teeth. Similarly, 68% of patients’ responses were “strongly disagree” or “disagree” considering their desire for replacing their teeth, and 76% of patients reported “strongly disagree” or “disagree” concerning evaluating if their teeth made them look older. A total of 16.0% of patients could not decide whether they are satisfied or not with in their response to these behavioral attitudes.

Patients' satisfaction level towards six measures describing their teeth, which included appearance, size, shape, color, position, and the appearance of the gum, was assessed. The patients’ sample indicated satisfaction with mean scores of 3.56 for gum appearance, and 3.72 for teeth appearance and the positioning of teeth. However, patients provided a lower satisfaction level regarding their teeth color (Figure 5).

Patients’ agreement level regarding the five negative self-behavioral attitudes related to their reaction to smile and teeth appearance was assessed. In general, the patients’ sample disagreed with most items, giving mean scores of 1.84 for “strange teeth” and 2.32 for “black space”. Patients strongly disagreed that their teeth could make them look older, with mean score of 1.68. Moreover, patients who did not undergo orthodontic treatment showed lower satisfaction with gum appearance scoring 3.32 and tended to hide their teeth with mean score 2.58 compared to those who received orthodontic treatment. Furthermore, patients who did not have filler treatment expressed lower satisfaction with tooth size (mean score: 3.67) when compared with those who had filler treatment (mean score: 4.00).

The layperson sample consisted of 488 randomly selected participants, with 86.1% female and 13.9% male. In terms of age distribution, the majority (60.2%) were aged 27 or younger, while 28.0% were aged between 28-years-old and 43-years-old, and the lowest percentage was aged 44 or older. Moreover, most of the participants had a bachelor’s degree and their monthly income extended from 10000 to 30000 Saudi Riyal.

In the laypersons’ sample, there was a significant difference in their perception of aesthetic smiles and dental appearances in photos “with lips” and “without lips”. Among the patients’ photos, 46 had higher aesthetic perception when lips were present. The highest-rated aesthetic photo, according to laypersons’ perception achieved a maximum mean value of (8.18 ± 1.99) “with lips” and (6.53 ± 2.74) “without lips”. In contrast, the photos that were considered (absolutely unaesthetic) by laypersons received scores of 1.73 ± 1.95 “with lips” and 1.0 8 ± 1.74 “without lips”. These findings show a significant difference in mean perception scores among laypersons for photos “with lips” compared to those “without lips” in most of the pictures.

Furthermore, female laypersons had higher perception mean scores compared to males. There were significant differences in perception mean scores among laypersons based on their educational background. The least significant difference post-hoc test was used to determine the significant differences within the educational background categories for laypersons. The mean scores for laypersons with an intermediate level of education were higher than those for laypersons in the Secondary, Bachelor, and PhD groups, with P values < 0.05 (0.001, 0.002, and 0.048) and mean differences of 1.89, 1.62 and 1.80, respectively. These findings suggest that laypersons with an intermediate level of education tend to have a higher aesthetical mean score when compared to laypersons in the Secondary, Bachelor, and PhD education groups.

Regarding laypersons’ income, significant differences were observed in perception mean scores. Laypersons with an income of more than 30000 obtained a higher aesthetical mean score for the group “without lips” compared to laypersons in both the less than 10000 and the 10000-30000 income groups.

Out of the 90 randomly selected dentists, the majority were females representing 82.2% of the sample, and the remaining 17.8% consisted of males. More than 57.8% were under the age of 30. The majority (85.6%) of the dentists' sample were Saudi, while the remaining were non- Saudi, regardless of the nationality. The highest percentage (97.7%) of the dentists’ sample worked in academic institutes and governmental hospitals, while only 2.2% held jobs in the private sector. Most dentists in the sample had between 1 year to 4 years of professional experience, which is compatible with the sample's age.

For the dentist sample, the perception of aesthetic smile and dental appearance in photos, “with lips” and “without lips”, was similar among 23 of the patients. The highest mean value for dentists' perceptions was recorded with photos that included lips, with a mean score of 7.83 ± 1.962, and for the same photo without lips, the mean score was 7.67 ± 2.208. These findings suggest that the smile and dental appearance were both considered as aesthetic parameters from dentists' points of view. Furthermore, the lowest mean value for dentists' perceptions were recorded in photos “with lips”, with a mean score of 2.20 ± 1.819 and for the same photo “without lips”, the mean score was 1.97 ± 1.839, This suggests that both the smile and dental appearance were considered unaesthetic parameter according to dentists’ opinion. In general, female dentists tended to give higher perception scores in comparison to males in the same profession.

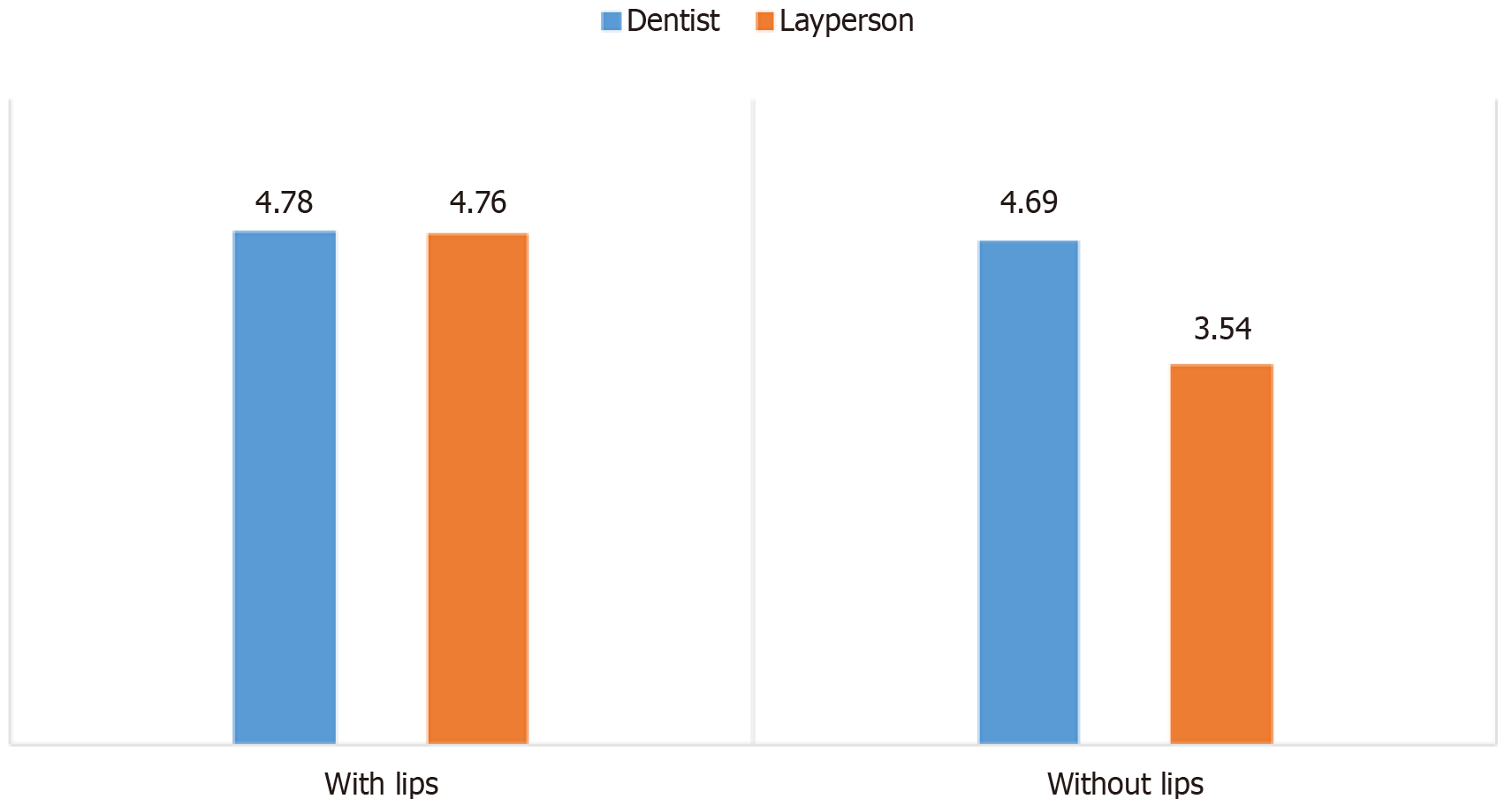

A positive moderate correlation existed between patients' satisfaction with their dental appearance and the assessments made by both laypersons and dentists for patients’ pictures, whether with or without lips. Furthermore, there was a strong and positive significant relationship between laypersons' perception and dentists' perception mean scores for pictures, with and without lips. There was no significant difference in perception mean scores between dentists and laypersons when evaluating pictures “with lips”, whereas the main difference was found in the evaluation of pictures “without lips”. Laypersons gave a mean score of 5.26 ± 2.54 for pictures “with lips” and 2.65 ± 2.53 for pictures “without lips”. In contrast, dentists’ mean scores were 5.33 ± 2.32 for pictures “with lips” and 4.77 ± 2.52 for pictures “without lips” (Figure 6).

Based on this study, patient satisfaction was significantly affected by certain aesthetic criteria, such as midline discrepancy, tooth shade, smile arc, width of smile line, presence of diastema, upper lip position, and upper lip curvature. However, there was no statistical evidence that patients’ satisfaction was affected by other criteria, including occlusal plane vs commissural line, upper inter-incisal line vs midline, labial corridor, as well as incisal curve vs lower lip.

Furthermore, there were statistically significant differences in laypersons’ perception mean scores between smile line, and incisal curve vs lower lip, with P values less than 0.05. There were no statistically significant differences in layperson's perception mean scores for tooth exposure at rest, incisal curve vs lower lip (contacting), smile width, labial corridor, and occlusal plane vs commissural line, with P values greater than 0.05.

Additionally, there were statistically significant differences in dentists’ perception mean scores for labial corridor, smile line, and incisal curve vs lower lip, with P values less than 0.05. In contrast, there was no statistical evidence that dentists’ perception was affected by upper inter-incisal line vs midline, incisal curve vs lower lip (contacting), and tooth exposure at rest aesthetic criteria.

Skin shade: Within the sample of patients, the majority, 60.0%, exhibited a light brown skin shade, while 24.0% had a medium brown skin tone. Beige and black skin shades each comprised 8% of the sample based on Fitzpatrick scale.

Upper lip position: Within the patient group, the distribution of upper lip position was as follows (Figure 7): 50% had an average upper lip position (Figure 7A), 46.0% had a low position upper lip (Figure 7B), and 14% had a high position or gummy smile (Figure 7C).

Upper lip curvature: Within the patient group, 62.0% exhibited a straight upper lip curvature (Figure 7A), 24.0% had a downward curvature (Figure 7E) and only 14.0% of the patients' sample had an upward upper lip curvature during smiling (Figure 7D).

Upper inter-incisal line vs midline: Most patients (60.0%) exhibited alignment in upper inter-incisal line vs midline (Figure 7A).

Buccal corridor: In the present study, 42.0% of the sample had a normal buccal corridor (Figure 7A).

Occlusal plane vs commissural line: The dental measurements revealed that (74.0%) of patients had an occlusal plane parallel to the commissural line (Figure 7A).

Midline discrepancy: In this study, 48% of patients presented proper dental midline coincidence (Figure 7G). In addition, 40.0% showed a midline discrepancy to the right, while 12.0% had a mild discrepancy to the left (Figure 7E and F).

Tooth shade: Among the patients’ sample, the highest percent (48.0%) had Reddish–Brownish tooth shade, at brightness level 1 and 2, with A2 being the highest. Next, 34.0% of the sample displayed Reddish–Yellowish tooth shades, at brightness level 1, 2 and 3, with shade B1 being the highest. Furthermore, 16.0% of the sample revealed greyish tooth shade at brightness level 1,2 and 3, with shade C1 being the highest. Lastly, only 2.0% of the patients' sample had Reddish–Grey tooth shade at brightness level 2, with shade D1.

Smile arc: In 36% of the patients’ sample, the bottom line of the upper teeth formed a consistent curve with the lower lip (Figure 7C). On the other hand, in 34% of patients, this alignment was not constant with the lower lip (Figure 7G), and only 30% had a straight smile arc (Figure 7B).

Width of smile line: The study found that most patients (76.0%) showed their first premolars during smiling. In contrast, 20.0% of patients tended to show their second premolars, and only 4.0% of patients showed their first molar when smiling. This smile line width can be categorized as narrow (Figure 7B), intermediate (Figure 7E), or wide (Figure 7G).

Presence of diastema between the central incisors: Diastema between the central incisors was absent for 94.0% of patients. Only 6.0% displayed a diastema between their central incisors (Figure 7H).

This study evaluated the aesthetic perception towards dental appearance as perceived by three entities: patients, laypersons and dentists. The patients were selected from diverse backgrounds as well as socioeconomic levels in order to explore their satisfaction with different aesthetic elements.

Patients’ teeth shade was measured using the digital shade detector (Ray Plicker). As, traditional chairside shade selection is known to be subjective due to various factors, including differences in viewer interpretation, external influences such as eye fatigue, aging, emotional state, lighting conditions, level of experience, and physiological variable such as color blindness. Therefore, electronic shade matching devices are used to address the limitations of traditional shade selection[20].

In the present study, most of the patients have a light brown skin shade. Vadavadagi et al[21] found a correlation between skin tone and tooth shade, suggesting that individuals with medium to dark skin tend to have teeth categorized with a high value resulting in darker shaded teeth compared to individuals with fair skin tones whose teeth have a low value[21]. The study by Esan et al[22] did not reveal any significant relationship between tooth shade and skin color[22].

In this study, patients were categorized according to the lip position to average upper lip position, low lip position, and high lip position (gummy smile). According to literature, the exposure of gingival tissue at smiling is not considered a negative aesthetic feature[23,24]. Kokich et al[24] evaluated female smiles and found that laypersons generally considered a 3 mm display of gingival tissue as aesthetically pleasing[24].

Notably in this study, most patients exhibited a straight upper lip curvature during smiling. In agreement with this finding, Hulsye’s mean score data indicated that the group with an upward lip curvature contained the largest number of subjects, while the group with a straight lip curvature included the fewest subjects. Additionally, this study reported that most patients displayed normal buccal corridors[25]. However, Krishnan et al[26] reported that intermediate buccal corridors are generally considered the most aesthetically pleasing when compared to wider or narrower buccal corridors[26].

In the current study, most patients exhibited parallel alignment of the occlusal plane with the commissural line. AlShamsi and AbuZayda[27] reported that the occlusal plane parallel to the commissural line is most preferred by both dental professionals and laypersons[27]. This aligns with the suggestions of Goldstein et al[28] and Dawson[29], suggesting that maintaining a parallel occlusal plane to a commissural line is essential for preserving natural facial harmony.

Most of the patients in this study displayed proper dental midline alignment. This observation is consistent with the findings of a study conducted by Priyadharshni et al[30], which reported that the dental midline coincided with facial midline for most of the female population[30].

In the present study, the parallel smile arc was the predominant smile amongst patients. This finding aligns with Tjan et al[31] study which suggested that the parallel smile arc was found to be the normal type of smile arc in untreated individuals, and generally is considered optimal and aesthetically pleasing[31]. Regarding smile width, our results indicate a higher prevalence of exposure to the first premolar (76.0%). This finding is consistent with Tjan et al[31], who found a high prevalence of first premolar exposure (48.6%). However, other studies have reported a greater prevalence of exposure to the second premolar[32,33]. This variance may be attributed to differences in the age composition of the sample studied.

In this study, it was observed that the presence of a diastema had an adverse effect on the perceived attractiveness of the smile, receiving the lowest score amongst all pictures (Figure 7H). The lower rating could be attributed to violation of the aesthetic principle of unity, harmony and balance. Kokich et al[24] and Geevarghese et al[7] observed that the midline diastema was not perceived as unattractive to neither dentists nor the public except when the gap between the central incisors exceeded 2.0 mm to 3.0 mm. Sabri et al[5], on the other hand, reported that a diastema exceeding 4 mm was linked with an unfavorable perception of an individual’s smile. Studies have shown that smiles that create a sense of unity are generally considered to be more attractive[2,34,35].

The majority of female patients expressed satisfaction according to their responses. This high satisfaction level could be attributed to several reasons; specifically, 62.0% of the sample had undergone orthodontic treatment while 8.0% had received lip fillers, indicating a greater motivational attitude to achieve an aesthetically pleasing smile. In line with our findings Negruțiu et al[9] and An et al[36] concluded that patients who had previously undergone orthodontic treatment exhibited a superior aesthetic perception compared to the control group without such treatment. Additionally, Alhaj et al[15] reported that individuals who have undergone orthodontic treatment or plastic surgery exhibited a positive impact on aesthetic perception.

However, when it comes to category of teeth color, most of the patients reported lower satisfaction levels[15]. The finding aligns with the findings of Alhaj et al[15], who also reported that teeth color received the lowest ratings when compared to facial and frontal profile assessments[15]. This emphasizes that teeth color is a sensitive and significant component of smile attractiveness[37]. This finding may be attributed to factors such as sex and age distribution within the sample. Research conducted by Vallittu et al[38], revealed that younger patients tend to prefer lighter tooth shade compared to the older individuals[38]. Similarly, Labban et al[19] found that female participants preferred lighter teeth shade than male participants[19].

The results of this study revealed that female laypersons tend to have higher mean scores perception than males. This aligns with Geron and Atalia[39], who reported statistically significant higher scores among female participants when evaluating smiles with upper gingival exposure[39]. This suggest that females may be more tolerant of upper gingival exposure. In contrast, our results differ from those of Zaugg et al[14], Alhaj et al[15] and Dudea et al[40] who reported that women tended to be more critical than men when assessing the presence of minor or major defects, while men were more accepting of different smiles. These differences could be attributed to a combination of sociocultural factors, individual preferences, and the specific characteristic of the study populations.

Furthermore, this study found that laypersons in the intermediate education group recorded higher level of aesthetical perception compared to laypersons in the Secondary, Bachelor, and PhD education groups. This observation agrees with Türkkahraman et al[41] findings, who noted that individuals with a primary school education had a lower ability to notice skeletal dysplasia compared to those with university level of education[41]. Furthermore, Alhaj et al[15] reported that individuals with a higher level of education tended to rate their orofacial appearance more favorably than those with low or no education[15]. Hence, it can be concluded that there is a positive correlation between education level and the refinement of aesthetic preferences.

In our study, age was found to play a significant factor in the perception of laypersons. This agrees with the results reported by Zaugg et al[14] and Rodrigues et al[42], who found differences in perception among various age groups, with younger individuals exhibiting a more critical assessment. Regarding the presence of a black triangle, a statistically significant difference was observed, indicating a decline in aesthetic perception for black triangle among patient aged over 40 years. These data are consistent with the research conducted by Pithon et al[43], who observed a decline in the aesthetic perception with advancing age. However, Sriphadungporn and Chamnannidiadha[44] found that older individuals exhibited a greater tolerance for a large black triangle size compared to younger individuals[44]. Addi

The findings of this study indicated that professional judgment of aesthetics, particularly in cases involving images “without lips”, varies significantly. Dentist may apply precise scientific criteria to evaluate such images, setting them apart from non-experts. Our research aligns with Kusnoto et al[45] who found that education within the dental field and knowledge acquisition can influence and alter individuals’ perceptions[45]. This finding is consistent with the results of Geevarghese et al[7], Khalaf et al[11] and Kokich et al[24] who reported that dentists possess a high ability to detect the most subtle changes in smile aesthetics compared to the general population.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. Firstly, the study focused on a sample of 50 female patients aged 18 to 40, which may not accurately reflect the broader population. Additionally, the study findings may be influenced by the specific demographics and cultural factors of the patients, as it was conducted exclusively within PNU dental clinics, potentially limiting the generalization of the results to different population. Moreover, it is worth noting that patients who volunteered for the study may have different aesthetic concerns or treatment histories which could have affected the study’s outcomes. Lastly, the use of two-dimensional, static images in the assessment, both for laypersons and dentists, may not fully capture the dynamic nature of aesthetic outcomes, which could impact the accuracy of assessments.

According to our analyses, the following conclusions could be drawn: (1) Orthodontic treatment positively affected patient satisfaction; (2) The presence of diastema negatively impacted the patient’s smile attractiveness; (3) Female laypersons had a better perception of aesthetic when compared to male laypersons; (4) Higher education level with higher socioeconomic status enhanced aesthetic perception; (5) Younger aged laypersons displayed a more critical eye for aesthetics when compared to the older population; and (6) Dentists’ aesthetic evaluation was more precise when compared to laypersons’ aesthetic judgement.

| 1. | Werner LL, der Graaff JV, Meeus WH, Branje SJ. Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence: Longitudinal Links with Maternal Empathy and Psychological Control. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44:1121-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Van Heck G, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Smile attractiveness. Self-perception and influence on personality. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:759-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Almanea R, Modimigh A, Almogren F, Alhazzani E. Perception of smile attractiveness among orthodontists, restorative dentists, and laypersons in Saudi Arabia. J Conserv Dent. 2019;22:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alomari SA, Alhaija ESA, AlWahadni AM, Al-Tawachi AK. Smile microesthetics as perceived by dental professionals and laypersons. Angle Orthod. 2022;92:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sabri NABM, Ridzwan SBB, Soo SY, Wong L, Tew IM. Smile Attractiveness and Treatment Needs of Maxillary Midline Diastema with Various Widths: Perception among Laypersons, Dental Students, and Dentists in Malaysia. Int J Dent. 2023;2023:9977868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zorlu M, Camcı H. The relationship between different levels of facial attractiveness and malocclusion perception: an eye tracking and survey study. Prog Orthod. 2023;24:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Geevarghese A, Baskaradoss JK, Alsalem M, Aldahash A, Alfayez W, Alduhaimi T, Alehaideb A, Alsammahi O. Perception of general dentists and laypersons towards altered smile aesthetics. J Orthod Sci. 2019;8:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Aldhorae K, Alqadasi B, Altawili ZM, Assiry A, Shamalah A, Al-Haidari SA. Perception of Dental Students and Laypersons to Altered Dentofacial Aesthetics. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2020;10:85-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Negruțiu BM, Moldovan AF, Staniș CE, Pusta CTJ, Moca AE, Vaida LL, Romanec C, Luchian I, Zetu IN, Todor BI. The Influence of Gingival Exposure on Smile Attractiveness as Perceived by Dentists and Laypersons. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miller CJ. The smile line as a guide to anterior esthetics. Dent Clin North Am. 1989;33:157-164. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Khalaf K, Seraj Z, Hussein H. Perception of Smile Aesthetics of Patients with Anterior Malocclusions and Lips Influence: A Comparison of Dental Professionals', Dental Students,' and Laypersons' Opinions. Int J Dent. 2020;2020:8870270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ward DH. Proportional Smile Design: Using the Recurring Esthetic Dental Proportion to Correlate the Widths and Lengths of the Maxillary Anterior Teeth with the Size of the Face. Dent Clin North Am. 2015;59:623-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Raj V, Heymann HO, Hershey HG, Ritter AV, Casko JS. The apparent contact dimension and covariates among orthodontically treated and nontreated subjects. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21:96-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zaugg FL, Molinero-Mourelle P, Abou-Ayash S, Schimmel M, Brägger U, Wittneben JG. The influence of age and gender on perception of orofacial esthetics among laypersons in Switzerland. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2022;34:959-968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alhajj MN, Ariffin Z, Celebić A, Alkheraif AA, Amran AG, Ismail IA. Perception of orofacial appearance among laypersons with diverse social and demographic status. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sabherwal RS, Gonzalez J, Naini FB. Assessing the influence of skin color and tooth shade value on perceived smile attractiveness. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:696-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mehl CJ, Harder S, Kern M, Wolfart S. Patients' and dentists' perception of dental appearance. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sachdeva S. Fitzpatrick skin typing: applications in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Labban N, Al-Otaibi H, Alayed A, Alshankiti K, Al-Enizy MA. Assessment of the influence of gender and skin color on the preference of tooth shade in Saudi population. Saudi Dent J. 2017;29:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim M, Kim B, Park B, Lee M, Won Y, Kim CY, Lee S. A Digital Shade-Matching Device for Dental Color Determination Using the Support Vector Machine Algorithm. Sensors (Basel). 2018;18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vadavadagi SV, Kumari KV, Choudhury GK, Vilekar AM, Das SS, Jena D, Kataraki B, B L B. Prevalence of Tooth Shade and its Correlation with Skin Colour - A Cross-sectional Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ZC72-ZC74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Esan TA, Olusile AO, Akeredolu PA. Factors influencing tooth shade selection for completely edentulous patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;7:80-87. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Suzuki L, Machado AW, Bittencourt MAV. An Evaluation of the Influence of Gingival Display Level in Smile Aesthetics. Dent Press J Orthod. 2011;16:37-39. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11:311-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hulsey CM. An esthetic evaluation of lip-teeth relationships present in the smile. Am J Orthod. 1970;57:132-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krishnan V, Daniel ST, Lazar D, Asok A. Characterization of posed smile by using visual analog scale, smile arc, buccal corridor measures, and modified smile index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | AlShamsi A, AbuZayda M. The Evaluation of Smile Design by Lay People and Dentists in the UAE. Int J Dent Oral Health. 2020;6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Goldstein RE, Belinfante L, Nahai F. Change Your Smile. 3rd ed. United States: Quintessence, 1997. |

| 29. | Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. 2nd ed. United States: Mosby, 1989. |

| 30. | Priyadharshni S, Felicita A Sumathi. Prevalence of Maxillary Midline Shift in Female Patients Reported to Saveetha Dental College. Drug Inven Today. 2019;11:77-80. |

| 31. | Tjan AH, Miller GD, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51:24-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Al-Johany SS, Alqahtani AS, Alqahtani FY, Alzahrani AH. Evaluation of different esthetic smile criteria. Int J Prosthodont. 2011;24:64-70. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Maulik C, Nanda R. Dynamic smile analysis in young adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:307-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Valo TS. Anterior esthetics and the visual arts: beauty, elements of composition, and their clinical application to dentistry. Curr Opin Cosmet Dent. 1995;24-32. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Lombardi RE. The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;29:358-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | An SM, Choi SY, Chung YW, Jang TH, Kang KH. Comparing esthetic smile perceptions among laypersons with and without orthodontic treatment experience and dentists. Korean J Orthod. 2014;44:294-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Pavicic DK, Spalj S, Uhac I, Lajnert V. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Influence of Tooth Color Elements on Satisfaction with Smile Esthetics. Int J Prosthodont. 2017;30:156-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vallittu PK, Vallittu AS, Lassila VP. Dental aesthetics--a survey of attitudes in different groups of patients. J Dent. 1996;24:335-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Geron S, Atalia W. Influence of sex on the perception of oral and smile esthetics with different gingival display and incisal plane inclination. Angle Orthod. 2005;75 778-784 [PMID:16283815 DOI: 10.1043/0003-3219(2005)75. |

| 40. | Dudea D, Lasserre JF, Alb C, Culic B, Pop Ciutrila IS, Colosi H. Patients' perspective on dental aesthetics in a South-Eastern European community. J Dent. 2012;40 Suppl 1:e72-e81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Türkkahraman H, Gökalp H. Facial profile preferences among various layers of Turkish population. Angle Orthod. 2004;74:640-647. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Rodrigues Cde D, Magnani R, Machado MS, Oliveira OB. The perception of smile attractiveness. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:634-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Pithon MM, Bastos GW, Miranda NS, Sampaio T, Ribeiro TP, Nascimento LE, Coqueiro Rda S. Esthetic perception of black spaces between maxillary central incisors by different age groups. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;143:371-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sriphadungporn C, Chamnannidiadha N. Perception of smile esthetics by laypeople of different ages. Prog Orthod. 2017;18:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kusnoto J, Haryanto ST. Perceptions Differences in Smile Attractiveness Between Dental Students and Laypersons. J Indonesian Dent Assoc. 2021;4:29-34. [DOI] [Full Text] |