Published online Aug 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.4983

Revised: May 19, 2024

Accepted: May 28, 2024

Published online: August 6, 2024

Processing time: 85 Days and 19.2 Hours

Gastric cancer-related morbidity and mortality rates are high in China. Patients who have undergone gastric cancer surgery should receive six cycles of che

To quantitatively explore the effects of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)–based nursing on anxiety, depression, and QoL of elderly patients with postoperative intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer.

The clinical data of 129 older patients with intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer surgery who were treated and cared for in our hospital between January 2019 and December 2021 were examined retrospectively. Nine patients dropped out because of transfer, relocation, or death. According to the order of admissions, the patients were categorized into either a comparison group or an observation group according to the random number table, with 60 cases in each group.

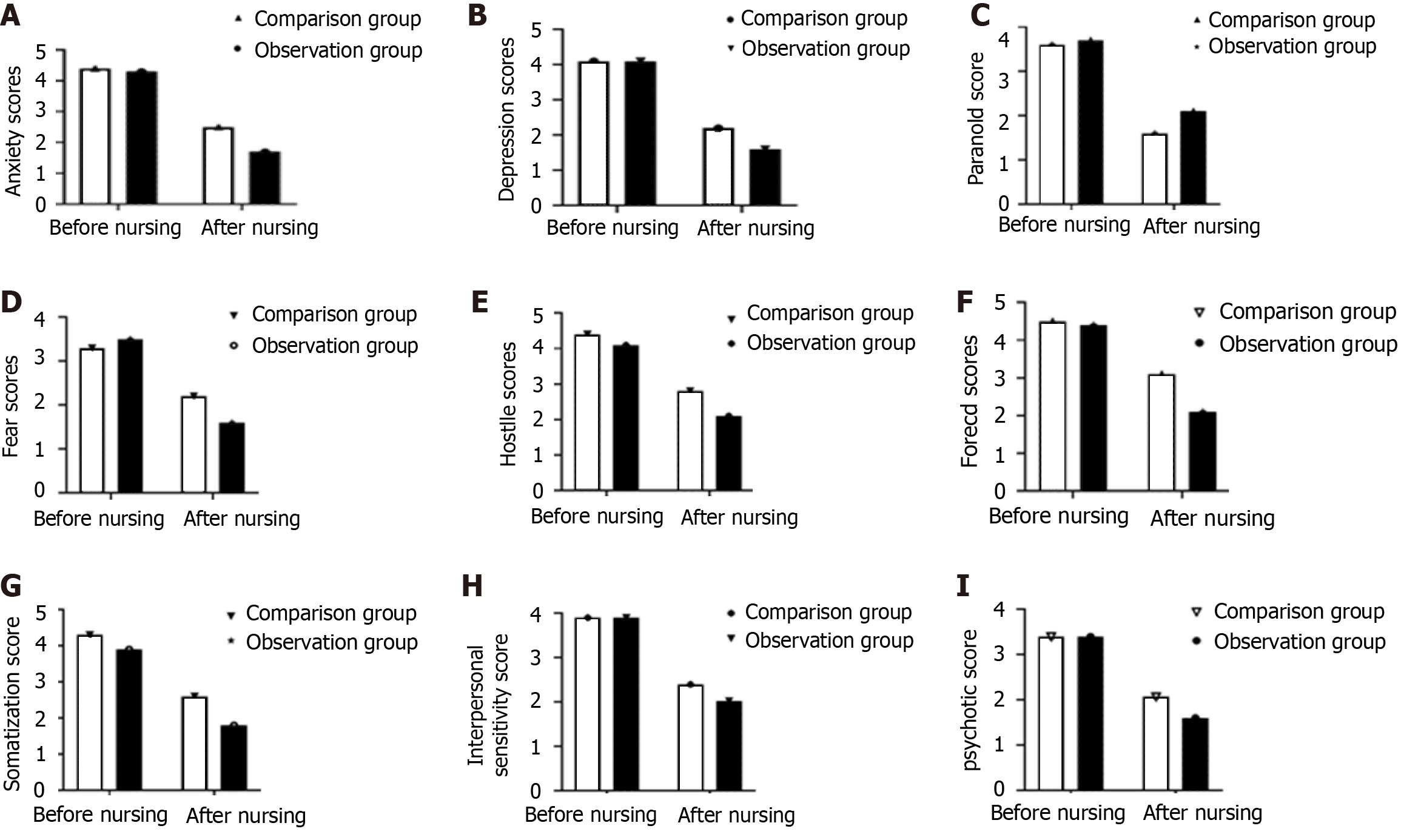

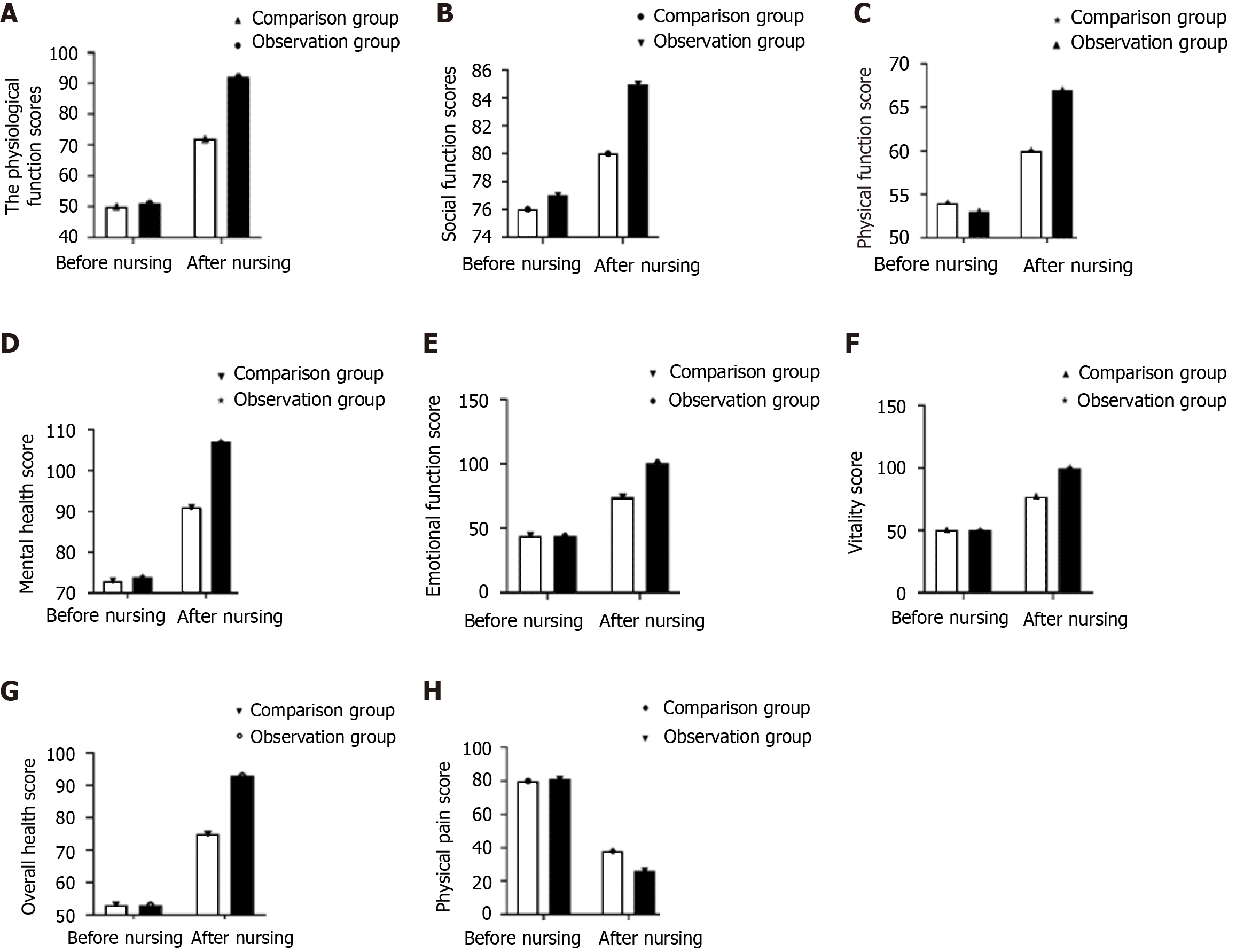

After nursing care, the observation group required significantly less time to eat for the first time, recover bowel sounds, pass gas, and defecate than the comparison group (P < 0.05). No significant difference was noted in nutrition-related indicators between the two groups before care. Before care, the Symptom Check List-90 scores between the two groups were comparable, whereas anxiety, depression, paranoia, fear, hostility, obsession, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and psychotic scores were significantly lower in the observation group after care (P < 0.05). The QoL scores between the two groups before care did not differ significantly. After care, the physical, social, physiological, and emotional function scores; mental health score; vitality score; and general health score were significantly higher in the observation group, whereas the somatic pain score was significantly lower in the observation group (P < 0.05).

ERAS-based nursing combined with conventional nursing interventions can effectively improve patient’s QoL, negative emotions, and nutritional status; accelerate the time to first ventilation; and promote intestinal function recovery in elderly patients with postoperative intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer surgery.

Core Tip: This study revealed that enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)-based nursing significantly improved gastrointestinal function, reduced adverse emotional states, and enhanced quality of life in elderly patients with postoperative intestinal obstruction following gastric cancer surgery. By integrating ERAS with traditional nursing interventions, patients experienced faster recovery of essential functions like eating and bowel movement, alongside notable improvements in nutritional status and psychological well-being. These findings underscore the effectiveness of ERAS in fostering a holistic recovery, suggesting its potential as a standard care component for postoperative management in this patient population.

- Citation: Li YQ, Liu Y, Peng ZQ, Fang R, Xu HY. Enhanced recovery after surgery-based nursing in older patients with postoperative intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer surgery: A retrospective study. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(22): 4983-4991

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i22/4983.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.4983

China has the highest incidence of gastric cancer worldwide. The main causes of gastric cancer include changes in diet, Helicobacter pylori infection, and excessive work pressure. Early gastric cancer can be treated via surgery, and pos

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS)–based nursing is based on evidence-based medicine to provide effective nursing measures for patients who undergo surgery, which can improve the gastrointestinal function and nutritional status of patients, relieve negative emotions, and improve the QoL[5]. Lombardi et al[6] applied ERAS-based nursing in patients with gastric cancer and demonstrated that these measures are safe and effective, benefiting the patients to a great extent in clinical practice. ERAS interventions mainly involve minimally invasive surgical techniques, optimal posto

In this study, the relevant principles of the third edition of “Medical Statistics” were used to calculate the sample size of 129 patients. Nine patients dropped out of the study at the 3-mo follow-up because of transfer, relocation, or death. The remaining patients were numbered according to the order of admission[7] and were categorized into either a comparison group or an observation group based on the random number table.

In the comparison group, the duration of gastric cancer was 2–11 (average, 6.18 ± 2.51) years, and there were 34 male and 26 female patients aged 41–67 (average, 75.91 ± 5.13) years. The tumor locations were the gastric antrum (n = 45), gastric body (n = 20), gastric fundus (n = 4), and multiple sites (n = 1). Moreover, the patients had poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 25), signet ring cell carcinoma (n = 15), moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 15), and mucinous adenocarcinoma (n = 5). Based on TNM staging, there were 20 cases of stages Ib and Ⅱ, 31 cases of stage III, and 9 cases of stage III. In addition, 37 patients were smokers, and 23 were nonsmokers.

In the observation group, the duration of gastric cancer was 3–11 (average, 6.01 ± 2.63) years. There were 33 male and 27 female patients aged 40–69 (average, 76.53 ± 5.44) years. The tumor locations were the gastric antrum (n = 45), gastric body (n = 18), gastric fundus (n = 6), and multiple sites (n = 1). Moreover, the patients had poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 26), signet ring cell carcinoma (n = 14), moderately and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (n = 14), and mucinous adenocarcinoma (n = 6). Based on TNM staging, there were 22 cases of stages Ib and II, 30 cases of stage III, and 8 cases of stage III. Furthermore, 35 patients were smokers, and 25 were nonsmokers. No significant difference was noted in baseline data such as duration of gastric cancer, sex, and age between the two groups.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) The diagnostic criteria for gastric cancer were in line with those specified in the Chinese Expert Consensus on Perioperative Nutritional Therapy for Gastric Cancer (2019 Edition)[8,9]. Gastric cancer was confirmed via electronic fiberoptic gastroscopy and pathological examination; (2) No distant metastasis was detected before surgery. All patients underwent laparoscopic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer, and complete case data were available; and (3) The patient was not malnourished before surgery, with a body mass index of > 18.5 kg/m2 and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification of grades I–III.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with a history of brain injury surgery, fractures, and joint lesions affecting normal activities; (2) Those who underwent general surgery in intensive care unit for > 72 h and experienced shock and unconsciousness after surgery; and (3) Those who underwent palliative surgery and had gastrointestinal obstruction and a history of constipation.

Conventional nursing interventions:

Preoperative care: (1) Understanding of surgery: A slide show of relevant knowledge was presented 1 h before surgery to make patients understand the surgical procedure and promote full cooperation of the family with the medical staff; (2) Diet: Patients were advised to drink 1–2 L of sugar water orally the night before surgery and fast from 00:00 in the morning; and (3) Intestinal preparation: 1000 mL of oral compound polyethylene glycol electrolyte was administered along with 1000 mL of warm water once each at 15:00 and 19:30 in the evening before surgery, followed by a full fluid dinner. A gastric tube was placed in the morning of the day of surgery.

Intraoperative care: After the patient’s admission to the operating room, he/she was placed in a suitable position, and the temperature and humidity of the operating room were adjusted.

Postoperative care: (1) Postoperative position: After the patient has awakened from anesthesia, he/she was asked to assume a left-sided or right-sided position. Six hours later, he/she was asked to assume a semi-prone position; (2) Pain. After the patient has returned to the ward without an analgesic pump, he/she was instructed to inform the medical staff about the need for pain relief if the pain is unbearable; and (3) Diet: On days 4–5 after surgery, the gastric tube cannot be removed immediately after anal discharge or defecation, and it was left in place for another 2–3 d. On day 8, the gastric tube was removed, and the patient was asked to drink fluids three times a day, 20–50 mL each time, and increase the amount on day 2 if there is no abdominal distension. The diet was shifted gradually from fluid to semi-fluid and general food. On day 2, the patient can get up and sit on the hospital bed. On day 3 after surgery, the patient can start to stand and walk around the bed.

ERAS-based nursing interventions:

Preoperative care: (1) Understanding of surgery. A slide show of relevant knowledge was played 1 h before surgery to help patients understand the surgical procedure and promote full cooperation of the family with the medical staff; (2) Diet: Patients were instructed to start fasting 4 h before surgery after administering 250 mL of oral surgical energy; and (3) Intestinal preparation: 1000 mL of polyethylene glycol electrolyte along with warm water was administered 1 d before surgery at 15:00 and 19:30, followed by a full fluid dinner. A gastric tube and liquid capsule jejunostomy tube were placed at 07:00.

Intraoperative care: (1) The operating room temperature was maintained at 25–28 ℃ and humidity at 45%–55%; (2) The intraoperative saline temperature was maintained at approximately 38 ℃; and (3) Attention was paid to the temperature of the exposed body part and heat preservation on the way back to the ward after surgery.

Postoperative care: (1) Postoperative position: After waking up from anesthesia, the patient was asked to assume a left-sided or right-sided position. Once the vital signs were stable, he/she was asked to assume a semi-prone position. Postoperative continuous use of an analgesic pump for pain relief was monitored, with strict control of the amount of infusion. At 24 h after surgery, the infusion was stopped, the urinary catheter was removed, and antibiotics were not administered. After waking up from anesthesia, 500 mL of warm saline was administered orally, with gradual resum

Changes in the QoL, nutritional status, dysphoria, and gastrointestinal function were compared between the observation and comparison groups before and after care. Regarding QoL, before care and at 3 mo postoperative follow-up, the QoL of the patients was assessed using a rating scale, which mainly encompasses physical function, somatic pain, social function, and physiological function, and the scores are positively correlated with the QOL. To assess nutritional status, pre- and postoperative blood samples were drawn from the patient’s elbow vein. Plasma was separated and stored at −20°C for measurements, and changes in prealbumin (PAB), Tet-responsive element (TRE), and albumin (ALB) levels were measured. Adverse emotions were assessed using the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90), with higher scores indicating more severe psychological symptoms. The abovementioned scales were completed independently within 30 min by the patient or accompanying family members before and 3 mo after care, without any internal or external influence.

All complete data were entered into a computer database using Epidata, and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 25.0 was used to statistically process the data. Data were entered into the computer database by a second person to ensure completeness and accuracy. The χ2 test was used to analyze the count data, expressed as percentages (%). Measurement data, presented as the mean ± standard deviation, were statistically analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test. P-values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

After nursing care, the time to first meal, time to recovery of bowel sounds, and time to exhaustion and defecation were significantly shorter in the observation group than in the comparison group (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| Comparison group (n = 60) | Observation group (n = 60) | t | P value | |

| Time to first meal (d) | 4.02 ± 0.05 | 3.95 ± 0.03 | 9.299 | 0.000 |

| Time to bowel sounds recovery (h) | 26.04 ± 0.15 | 19.05 ± 0.22 | 203.343 | 0.000 |

| Time to first anal exhaust (h) | 42.35 ± 0.24 | 25.28 ± 0.21 | 414.619 | 0.000 |

| Time to defecation (d) | 5.30 ± 0.27 | 3.52 ± 0.24 | 38.167 | 0.000 |

Before nursing care, no significant difference was noted in nutritional status-related indicators between the two groups. After nursing care, the PAB, TRE, and ALB levels were significantly lower in the observation group than in the comparison group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Comparison group (n = 60) | Observation group (n = 60) | t | P value | |

| PAB (g/L) | ||||

| Before nursing | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 1.879 | 0.063 |

| After nursing | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 17.187 | 0.000 |

| TRE (g/L) | ||||

| Before nursing | 2.56 ± 0.32 | 2.51 ± 0.29 | 0.897 | 0.372 |

| After nursing | 1.74 ± 0.12 | 2.26 ± 0.09 | 26.853 | 0.000 |

| ALB (g/L) | ||||

| Before nursing | 40.11 ± 0.07 | 40.14 ± 0.28 | 0.805 | 0.422 |

| After nursing | 35.23 ± 0.31 | 37.22 ± 0.44 | 28.639 | 0.000 |

Before nursing care, the SCL-90 scores of the two groups were comparable. After nursing care, the anxiety, depression, fear, hostility, compulsion, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and psychotic scores were significantly lower in the observation group than in the comparison group, whereas the paranoia score was significantly higher in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

No significant difference in the QoL scores was noted between the two groups before nursing care. After nursing care, the physical, social, physiological, and emotional function scores; mental health score; vitality score; and overall health score were significantly higher in the observation group than in the comparison group, whereas the physical pain score was significantly lower in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

The incidence of gastric cancer in China is increasing annually, and it ranks third in the incidence and mortality rates among all malignant tumors, seriously endangering the health of patients. Research on accelerated rehabilitation surgery for gastric cancer is limited. Currently, there are many challenges in solving the problems of rapid recovery in patients who underwent gastric cancer surgery. In 2007, Jiang et al[10] from Nanjing Military General Hospital first applied the ERAS-based nursing intervention in patients with gastric cancer and demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of the intervention. In 2010, the first international article on the safety and effectiveness of ERAS interventions for gastric cancer was published[11]. The safety and effectiveness of ERAS interventions for patients with gastric cancer were gradually confirmed at a later stage. These interventions are rapidly developing in the field of surgery in the medical community.

In this study, after nursing care, the times to first feeding, recovery of bowel sounds, venting, and defecation were shorter in the observation group than in the comparison group, indicating that ERAS-based nursing interventions can effectively improve the recovery of bowel function. The core goal of ERAS is to reduce patients’ surgical stress response and protect the immune system through effective measures to achieve rapid recovery. The results of this study showed that the times to anal exhaust, recovery of bowel sounds, fasting, and first bowel movement as well as postoperative hospital stay were shorter in patients undergoing laparoscopic gastric cancer resection who received ERAS-based nursing care than in those who received conventional nursing care. Thus, ERAS-based nursing care can promote the recovery of gastrointestinal function in patients with gastric cancer who have undergone laparoscopic surgery[12].

In this study, no significant difference was noted in the nutritional status-related indicators between the two groups before nursing care; however, after nursing care, the PAB, TRE, and ALB levels were higher in the observation group than in the comparison group. ERAS is a multidisciplinary, coordinated, and standardized approach to perioperative management that reduces surgical trauma, complications, and duration of stay and promotes functional recovery[13,14]. ERAS has been successfully applied in many surgical procedures, particularly in gastrocolorectal cancer[15], and its goals reflect the tenets of a new patient-centered medical model and are in line with the direction of surgical development[16]. This may be because ERAS, e.g., preoperative oral carbohydrate administration, decreases postoperative catabolism, reduces the negative nitrogen balance, and promotes postoperative gastrointestinal function recovery[17]. Compared with patients with other malignant tumors, those with gastric cancer have a relatively poor nutritional status, which affects various aspects of the immune system, leading to immunosuppression against the tumor, allowing for earlier metastasis and recurrence, and thus affecting the long-term prognosis.

In this study, after nursing care, the anxiety, depression, paranoia, fear, hostility, obsessive–compulsive, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and psychotic scores were lower in the observation group than in the comparison group, and ERAS-based nursing combined with conventional nursing interventions was found to effectively improve patients’ adverse emotions. Patients with cancer are extremely prone to negative psychology such as despair and pessimism because of their illness. Poor psychological status may directly affect patients’ postoperative recovery. The nursing staff can conduct effective psychological interventions through preoperative education to alleviate patients’ anxiety and reduce the stress caused by adverse emotions[18-20]. Preoperatively, patients must be instructed regarding appropriate physical exercise, and postoperatively, they are encouraged to get out of bed as early as possible, which may promote early postoperative gastric motility and gastrointestinal function recovery[21-23].

After nursing care, the physical, social, physiological, and emotional function scores; mental health score; vitality score; and overall health score were significantly higher in the observation group than in the comparison group, whereas the somatic pain score was lower in the observation group, indicating that ERAS-based nursing combined with conventional nursing interventions can effectively improve patients’ QoL. This finding cannot be attributed to a single factor but to the combination of ERAS-based nursing and conventional nursing interventions to improve the psychological, physiological, and nutritional status of the patients and thus their QoL[24-26].

This study has some limitations. The inclusion of patients with intestinal obstruction following gastric cancer surgery was not according to the gastric cancer stage, and only older patients were recruited; thus, the results of this study may be biased and may not be representative of the general population. This study only investigated the effect of ERAS-based nursing on the recovery of older patients with intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer surgery and failed to comprehensively assess the reliability of care for these patients. Moreover, an in-depth study and long-term follow-up on the recovery of the study patients were not conducted.

ERAS-based nursing combined with conventional nursing interventions can effectively improve patients’ QoL and adverse emotions, improve nutritional status, and promote intestinal function recovery. This study provides some reference for nursing care of patients with intestinal obstruction after gastric cancer surgery.

| 1. | Davis JL, Ripley RT. Postgastrectomy Syndromes and Nutritional Considerations Following Gastric Surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:277-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Hyung WJ, Yang HK, Park YK, Lee HJ, An JY, Kim W, Kim HI, Kim HH, Ryu SW, Hur H, Kim MC, Kong SH, Cho GS, Kim JJ, Park DJ, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Kim JW, Lee JH, Han SU; Korean Laparoendoscopic Gastrointestinal Surgery Study Group. Long-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer: The KLASS-02-RCT Randomized Clinical Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3304-3313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 53.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Konishi T, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Konishi H, Takemoto K, Kudou M, Shoda K, Arita T, Kosuga T, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Kubota T, Nakanishi M, Okamoto K, Otsuji E. Comparison of Feeding Jejunostomy via Gastric Tube Versus Jejunum After Esophageal Cancer Surgery. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:4941-4945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li P, Lin JX, Tu RH, Lu J, Xie JW, Wang JB, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Huang ZN, Lin JL, Zheng CH, Huang CM. Early unplanned reoperations after gastrectomy for gastric cancer are different between laparoscopic surgery and open surgery. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:4133-4142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee Y, Yu J, Doumouras AG, Li J, Hong D. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) versus standard recovery for elective gastric cancer surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Oncol. 2020;32:75-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lombardi PM, Mazzola M, Giani A, Baleri S, Maspero M, De Martini P, Gualtierotti M, Ferrari G. ERAS pathway for gastric cancer surgery: adherence, outcomes and prognostic factors for compliance in a Western centre. Updates Surg. 2021;73:1857-1865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xu YY, Sun ZQ, Yan H. Medical Statistics (Third Edition)/Higher Education Textbook. Higher Education Press: 2021; 61-65.. |

| 8. | Cardiac Critical Care Medicine Of China Internationgnal Exchange And Promotion For Medical And Healthcare; Nutrition Support Expert Committee Of Chinese Cardiac Critical Care Medicine. [Chinese consensus guideline for nutrition support therapy in the perioperative period of adult cardiac surgery in 2019]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2019;31:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pan T, Galiullin D, Chen XL, Zhang WH, Yang K, Liu K, Zhao LY, Chen XZ, Hu JK. Incidence of adhesive small bowel obstruction after gastrectomy for gastric cancer and its risk factors: a long-term retrospective cohort study from a high-volume institution in China. Updates Surg. 2021;73:615-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jiang ZW, Li JS, Wang ZM, Li N, Liu XX, Li WY, Zhu SH, Diao YQ, E YJ, Huang XJ. The safety and efficiency of fast track surgery in gastric cancer patients undergoing D2 gastrectomy. Zhonghua Waike Zazhi. 2007;45:1314-1317. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Liu XX, Jiang ZW, Wang ZM, Li JS. Multimodal optimization of surgical care shows beneficial outcome in gastrectomy surgery. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34:313-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kang SH, Lee Y, Min SH, Park YS, Ahn SH, Park DJ, Kim HH. Multimodal Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Program is the Optimal Perioperative Care in Patients Undergoing Totally Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: A Prospective, Randomized, Clinical Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3231-3238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hur H, Roh CK, Son SY, Han SU. How could we make clinical evidence for early recovery after surgery (ERAS) in minimally invasive surgery for gastric cancer? J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:361-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aoyama T, Yoshikawa T, Sato T, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Ogata T, Cho H. Equivalent feasibility and safety of perioperative care by ERAS in open and laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a single-institution ancillary study using the patient cohort enrolled in the JCOG0912 phase III trial. Gastric Cancer. 2019;22:617-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhou J, Lin S, Sun S, Zheng C, Wang J, He Q. Effect of single-incision laparoscopic distal gastrectomy guided by ERAS and the influence on immune function. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19:307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li MZ, Wu WH, Li L, Zhou XF, Zhu HL, Li JF, He YL. Is ERAS effective and safe in laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma? A meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang WK, Tu CY, Shao CX, Chen W, Zhou QY, Zhu JD, Xu HT. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery on postoperative rehabilitation, inflammation, and immunity in gastric carcinoma patients: a randomized clinical trial. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2019;52:e8265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lu J, Tao P, Li H, Wu G, Wang C, Zhang J, Dou X, Han Z, Chen H. Auditory and Visual Stimulation for Abdominal Postoperative Patients Experiencing Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS). Gastroenterol Nurs. 2021;44:116-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Noba L, Rodgers S, Chandler C, Balfour A, Hariharan D, Yip VS. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Reduces Hospital Costs and Improve Clinical Outcomes in Liver Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:918-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou J, Peng ZF, Song P, Yang LC, Liu ZH, Shi SK, Wang LC, Chen JH, Liu LR, Dong Q. Enhanced recovery after surgery in transurethral surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Asian J Androl. 2023;25:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tian Y, Cao S, Liu X, Li L, He Q, Jiang L, Wang X, Chu X, Wang H, Xia L, Ding Y, Mao W, Hui X, Shi Y, Zhang H, Niu Z, Li Z, Jiang H, Kehlet H, Zhou Y. Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Short-term Outcomes of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery and Conventional Care in Laparoscopic Distal Gastrectomy (GISSG1901). Ann Surg. 2022;275:e15-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Purcell LN, Marulanda K, Egberg M, Mangat S, McCauley C, Chaumont N, Sadiq TS, Lupa C, McNaull P, McLean SE, Hayes-Jordan A, Phillips MR. An enhanced recovery after surgery pathway in pediatric colorectal surgery improves patient outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ying Y, Xu HZ, Han ML. Enhanced recovery after surgery strategy to shorten perioperative fasting in children undergoing non-gastrointestinal surgery: A prospective study. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:5287-5296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zuo L, Liu S, Yang X. Efficiency of Perioperative Comfort Care and Its Impact on Postoperative Recovery of Breast Cancer Patients. J Mod Nurs Pract Res. 2022;2:6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Pędziwiatr M, Mavrikis J, Witowski J, Adamos A, Major P, Nowakowski M, Budzyński A. Current status of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol in gastrointestinal surgery. Med Oncol. 2018;35:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, Schäfer M, Mariette C, Braga M, Carli F, Demartines N, Griffin SM, Lassen K; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Group. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1209-1229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |