Published online Aug 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.4865

Revised: May 23, 2024

Accepted: June 11, 2024

Published online: August 6, 2024

Processing time: 74 Days and 4.6 Hours

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a leading cause of maternal mortality, and hysterectomy is an important intervention for managing intractable PPH. Accu

To develop a risk prediction model for PPH requiring hysterectomy in the ethnic minority regions of Qiandongnan, China, to help guide clinical decision-making.

The study included 23490 patients, with 1050 having experienced PPH and 74 who underwent hysterectomies. The independent risk factors closely associated with the necessity for hysterectomy were analyzed to construct a risk prediction model, and its predictive efficacy was subsequently evaluated.

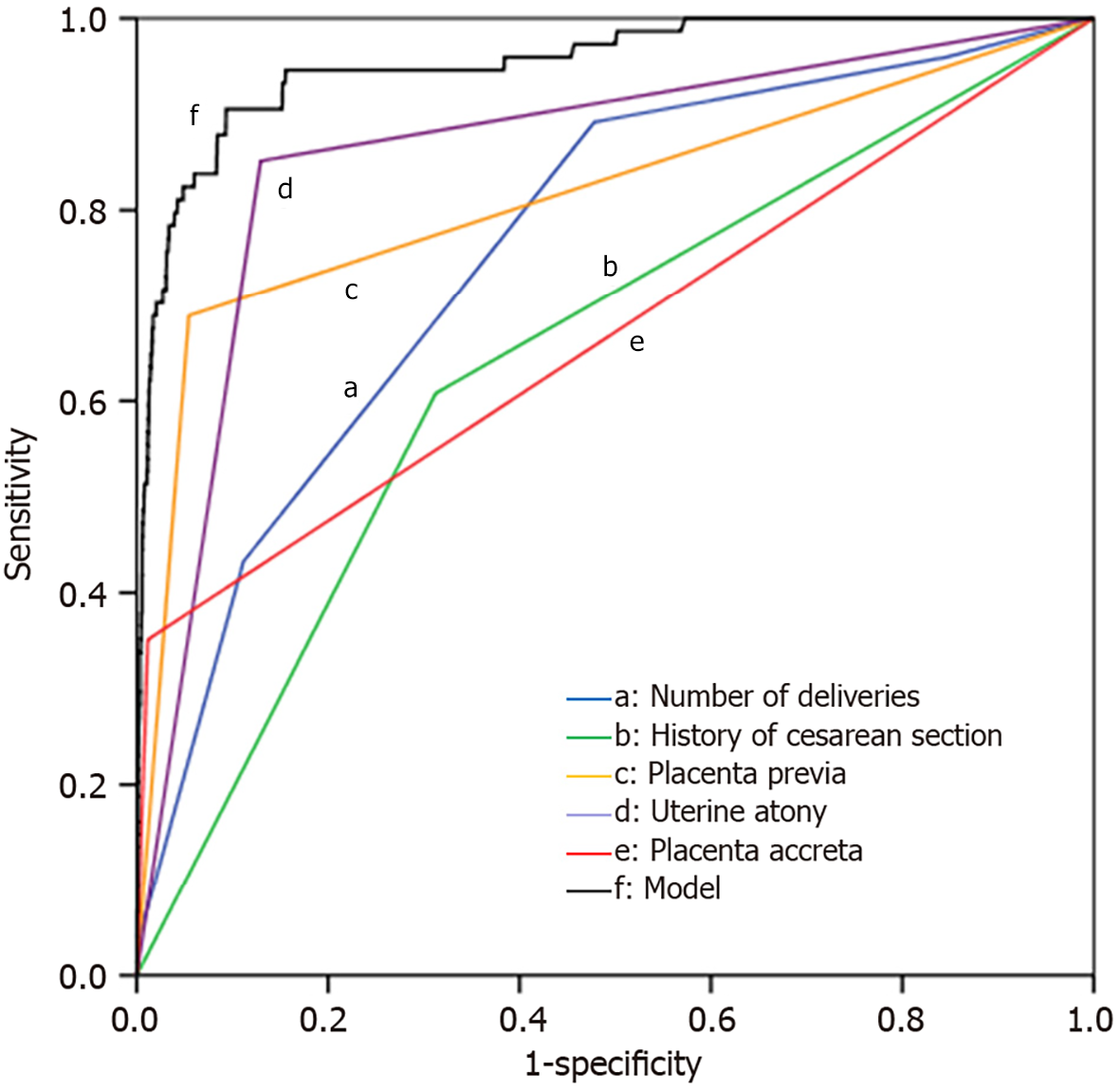

The proportion of hysterectomies among the included patients was 0.32% (74/23490), representing 7.05% (74/1050) of PPH cases. The number of deliveries, history of cesarean section, placenta previa, uterine atony, and placenta accreta were identified in this population as independent risk factors for requiring a hysterectomy. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of the prediction model showed an area under the curve of 0.953 (95% confidence interval: 0.928-0.978) with a sensitivity of 90.50% and a specificity of 90.70%.

The model demonstrates excellent predictive power and is effective in guiding clinical decisions regarding PPH in the ethnic minority regions of Qiandongnan, China.

Core Tip: This study developed a risk prediction model for hysterectomy following postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) in ethnic minority regions. A total of 23490 patients were included, with 1050 cases of PPH and 74 cases undergoing hysterectomy, accounting for 7.05% of PPH cases. History of cesarean section, placenta previa, uterine atony, placenta accreta and multiple deliveries were identified as independent risk factors for hysterectomy. The model demonstrated strong predictive capability, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.953, sensitivity of 90.50%, and specificity of 90.70%. This model provides valuable guidance for clinical decision-making regarding PPH.

- Citation: Wang L, Pan JY. Predictive model for postpartum hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy in a minority ethnic region. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(22): 4865-4872

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i22/4865.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i22.4865

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the most common and severe complications in obstetrics, representing a leading cause of maternal mortality[1,2]. With increasing cesarean delivery rates and advancing maternal age, there is an upward trend in the incidence of PPH[3,4]. Despite the existence of several effective clinical prevention and treatment methods, studies have shown that PPH mortality rates remain alarmingly high, ranging from 0.0% to 40.7% with a global average of 6.6%, particularly in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, with significant differences observed between different ethnicities[5]. Women experiencing persistent bleeding are at an elevated risk of death[6,7]. As one of the essential measures for managing intractable PPH, emergency hysterectomy can save lives and significantly reduce mortality rates[8].

The Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture spans 30300 square kilometers and has a population of 4.88 million. Ethnic minorities make up 81.7% of this population, with 43.4% being Miao and 30.5% being Dong. This region boasts a rich cultural heritage and a significant history, serving as the core of Chinese Miao and Dong culture. Factors such as race[9], culture, and the economy influence the treatment options that pregnant and postpartum women have access to.

This study developed a predictive model for PPH requiring hysterectomy in the minority region of Qiandongnan in China to facilitate clinical practice guidance.

Between January 1, 2018, and January 10, 2024, a total of 23,520 cases were selected from the obstetrics and intensive care units at the People's Hospital of Qiandongnan Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture (a tertiary hospital), all of whom were members of ethnic minorities from Qiandongnan, China. Twenty-five cases who opted out of delivering at the hospital were excluded from this study. In addition, another 5 patients were excluded because they had coagulation dysfunction prior to childbirth (defined as prothrombin time longer than 15 s and/or activated partial thromboplastin time longer than 35 s), resulting in a total of 23490 patients ultimately being included in the study. The age of these patients ranged from 18 years to 48 years, with an average age of (31.11 ± 5.59) years. On average, the patients had experienced (3.07 ± 2.51) pregnancies and (1.46 ± 0.94) deliveries. Of the 23490 patients, 1050 had experienced PPH (4.47%), including 74 cases classified as intractable PPH with concomitant hysterectomy, with an incidence rate of 0.32%, accounting for 7.05% of the total PPH cases. Notably, 7357 cases had a history of cesarean section (31.31%), 1324 cases had a history of placenta previa (5.64%), 3099 cases had a history of uterine atony (13.19%), and 297 cases had a history of placenta accreta (1.26%). During the study period, 13525 cases underwent cesarean delivery (57.58%), while 399 cases received uterine artery embolization (1.70%). Five deaths were reported (0.02%).

Upon admission, patients underwent necessary examinations, including ultrasound for fetal and amniotic fluid assessment, coagulation function testing, blood glucose assessment, and pelvic measurement. In the event of PPH, appropriate measures were taken to stop the bleeding based on the cause and to implement necessary supportive treatments. This included intravenous drip of tranexamic acid (1 g), early fluid replenishment, and blood transfusion to maintain blood pressure, as well as continuous intravenous drip of oxytocin (1.2-2.4 U/h) for cases of uterine atony. When necessary, we resorted to pelvic and vaginal packing for pressure hemostasis, pelvic blood vessel ligation, and transcatheter uterine artery embolization. If these treatments proved ineffective, a subtotal hysterectomy was performed. In cases involving placenta previa or partial placenta accreta in the cervix, a total hysterectomy was conducted. These treatment protocols were in accordance with the Chinese guidelines for the prevention and management of PPH[10].

The diagnostic criteria for PPH included clinical manifestations with blood loss exceeding 500 mL after vaginal delivery and 1000 mL after cesarean delivery[11]. Conditions necessitating hysterectomy for refractory PPH included either of the following: (1) Massive bleeding during or after delivery leading to coagulopathy, hemodynamic instability, and failure of conservative treatment, requiring emergency hysterectomy to save the patient's life; and (2) PPH in which active conservative treatment was ineffective and bleeding remained uncontrolled after uterine artery ligation and/or embolization, necessitating hysterectomy for treatment.

After patient discharge, we collected relevant diagnostic and treatment information, including age, number of pre

We used SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) for data analysis. Count data are expressed as cases (%), with comparisons between groups made using the χ² test, while measurement data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, with comparisons between groups made using the independent samples t-test. Independent risk factors were analyzed using binary logistic regression, and the predictive abilities of various indicators for PPH requiring hysterectomy were analyzed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We compared the clinical data of patients in the hysterectomy and non-hysterectomy groups. The results showed that the proportions of age, number of deliveries, advanced maternal age, history of cesarean section, history of adverse obstetric or perinatal events, non-cephalic presentation, placenta previa, preterm birth, uterine atony, uterine rupture, retained placenta, placenta accreta, and placenta adhesion were significantly higher in the hysterectomy group than in the non-hysterectomy group (t/χ² = 6.790, -5.491, 21.161, 27.270, 14.110, 5.255, 206.070, 44.585, 197.174, 4.739, 4.894, 134.759, 6.035; P < 0.05), while the proportions of post-term pregnancy and the premature rupture of membranes were lower in the hysterectomy group (χ² = 13.396, 4.514; P < 0.05); these differences were statistically significant. Detailed data are shown in Table 1.

| Parameters | Hysterectomy group, n = 74 | Non-hysterectomy group, n = 990 | χ2/t | P value |

| Age in yr | 34.51 ± 4.31 | 31.10 ± 5.59 | 6.790 | 0.000 |

| Number of pregnancies | 4.12 ± 1.97 | 3.06 ± 2.52 | -0.230 | 0.818 |

| Number of deliveries | 2.43 ± 1.04 | 1.46 ± 1.93 | -5.491 | 0.000 |

| Advanced maternal age | 38 (51.35) | 6123 (26.15) | 21.161 | 0.000 |

| Assisted reproductive technology | 5 (6.76) | 1369 (5.85) | 0.106 | 0.802 |

| Macrosomia | 0 (0.00) | 819 (3.50) | 5.261 | 0.087 |

| Twins | 3 (4.05) | 999 (4.27) | 0.008 | 0.928 |

| History of cesarean section | 45 (60.81) | 7312 (31.23) | 27.270 | 0.000 |

| History of adverse obstetric or perinatal events | 27 (36.49) | 4212 (17.99) | 14.110 | 0.000 |

| Non-cephalic presentation | 30 (40.54) | 6580 (28.10) | 5.255 | 0.027 |

| Stillbirth | 0 (0.00) | 146 (0.62) | 0.924 | 0.708 |

| Uterine fibroids | 0 (0.00) | 336 (1.43) | 2.136 | 0.434 |

| Placenta previa | 51 (68.92) | 1273 (5.44) | 206.070 | 0.000 |

| Nuchal cord | 22 (29.73) | 6166 (26.33) | 0.428 | 0.597 |

| Pre-pregnancy hypertension | 1 (1.35) | 858 (3.66) | 1.465 | 0.375 |

| Gestational hypertension | 1 (1.35) | 549 (2.34) | 0.374 | 0.731 |

| Eclampsia | 5 (6.76) | 1084 (4.63) | 0.666 | 0.586 |

| HELLP syndrome | 0 (0.00) | 19 (0.08) | 0.120 | 0.729 |

| Gestational diabetes | 4 (5.41) | 1802 (7.70) | 0.603 | 0.526 |

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | 4 (5.41) | 1931 (8.25) | 0.888 | 0.414 |

| History of pelvic inflammatory disease | 5 (6.76) | 1165 (4.98) | 0.445 | 0.588 |

| History of vaginitis | 2 (2.70) | 1703 (7.27) | 2.961 | 0.129 |

| History of endometrial infection | 2 (2.70) | 545 (2.33) | 0.043 | 0.835 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 (1.35) | 250 (1.07) | 0.052 | 0.820 |

| Polyhydramnios | 0 (0.00) | 159 (0.68) | 1.007 | 0.694 |

| Oligohydramnios | 2 (2.70) | 1529 (6.53) | 2.244 | 0.182 |

| Post-term pregnancy | 4 (5.41) | 3751 (16.02) | 13.396 | 0.005 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | 1 (1.35) | 620 (2.65) | 0.585 | 0.546 |

| Induced labor | 0 (0.00) | 857 (3.66) | 5.509 | 0.069 |

| Preterm birth | 32 (43.24) | 2817 (12.03) | 44.585 | 0.000 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 5 (6.76) | 3445 (14.71) | 4.514 | 0.034 |

| Placental abruption | 1 (1.35) | 131 (0.56) | 0.594 | 0.441 |

| Uterine atony | 63 (85.14) | 3036 (12.97) | 197.174 | 0.000 |

| Uterine rupture | 2 (2.70) | 81 (0.35) | 4.739 | 0.028 |

| Retained placenta | 1 (1.35) | 10 (0.04) | 4.894 | 0.034 |

| Placenta accreta | 26 (35.14) | 271 (1.16) | 134.759 | 0.000 |

| Placenta adhesion | 53 (71.62) | 13537 (57.81) | 6.035 | 0.018 |

| Perineal tears | 0 (0.00) | 223 (0.95) | 1.414 | 0.649 |

| Cesarean delivery | 46 (62.16) | 13479 (57.56) | 4.547 | 0.482 |

Using the indicators with P < 0.05 in Table 1 as independent variables (all categorical variables were dichotomized, with yes = 1 and no = 0) and whether a hysterectomy was performed (yes = 1, no = 0) as the dependent variable, a binary logistic regression analysis was conducted using the Wald method. The results identified the number of deliveries, as well as histories of cesarean section, placenta previa, uterine atony, and placenta accreta as independent risk factors for hysterectomy, as shown in Table 2.

| Parameters | β | SE | Wald χ2 | P value | OR | OR (95%CI) |

| Age | 0.042 | 0.023 | 3.153 | 0.076 | 1.043 | 0.996-1.092 |

| Number of deliveries | 0.493 | 0.123 | 16.136 | 0.000 | 1.637 | 1.287-2.083 |

| History of cesarean section | 0.601 | 0.260 | 5.341 | 0.021 | 1.824 | 1.096-3.036 |

| History of adverse obstetric or perinatal events | 0.475 | 0.266 | 3.189 | 0.074 | 1.607 | 0.955-2.706 |

| Placenta previa | 2.237 | 0.284 | 61.853 | 0.000 | 9.367 | 5.364-16.359 |

| Uterine atony | 2.663 | 0.345 | 59.598 | 0.000 | 14.343 | 7.294-28.202 |

| Placenta accreta | 1.505 | 0.292 | 26.559 | 0.000 | 4.504 | 2.541-7.984 |

| Constant | -10.565 | 0.872 | 146.709 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Based on the results of the logistic regression analysis, we refined the model using the five variables with P < 0.05. All variables included in the equation maintained their significance with P < 0.05. The final hysterectomy risk prediction model was formulated as: logit (P) = 0.493 × number of deliveries + 0.601 × history of cesarean section (yes = 1, no = 0) + 2.237 × placenta previa (yes = 1, no = 0) + 2.663 × uterine atony (yes = 1, no = 0) + 1.505 × placenta accreta (yes = 1, no = 0) − 10.565. To assess the predictive ability of the hysterectomy risk prediction model, we used ROC curve analysis with actual hysterectomy as the standard. The results showed that the area under the curve (AUC) for the hysterectomy risk prediction model was 0.953 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.928–0.978), with a sensitivity of 90.50% and a specificity of 90.70%. The predictive performance of this model surpassed that of any single parameter, as shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

| Parameters | AUC | AUC (95%CI) | Cut off value | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Youden index |

| Model | 0.953 | 0.928-0.978 | 0.003 | 90.50 | 90.70 | 0.812 |

| Number of deliveries | 0.760 | 0.707-0.813 | 1.5 | 89.20 | 55.20 | 0.444 |

| History of cesarean section | 0.648 | 0.583-0.712 | Yes | 60.80 | 68.70 | 0.295 |

| Placenta previa | 0.817 | 0.754-0.881 | Yes | 68.90 | 84.50 | 0.534 |

| Uterine atony | 0.861 | 0.814-0.908 | Yes | 85.10 | 87.00 | 0.721 |

| Placenta accreta | 0.670 | 0.594-0.745 | Yes | 35.10 | 88.80 | 0.239 |

The severity of PPH lies in the possibility of it rapidly leading to hemorrhagic shock, thereby posing a severe threat to the patient's life. Hysterectomy, which is considered an extreme measure, is usually adopted only after other conservative treatments have proven ineffective[12], and thus plays a crucial role in saving maternal lives. Studies have suggested that the incidence of hysterectomy is 7.6‰ (453690/59854731), with noticeable racial disparities[13]. Other studies have also indicated significant differences in the occurrence and outcomes of PPH across different regions and ethnic groups[14-16].

In the ethnically diverse region of Qiandongnan, China, which is characterized by a relatively underdeveloped economy, there exist rich and unique ethnic cultures; however, women often hold traditional views on preserving the uterus in the face of PPH. This study explored PPH management strategies in the context of unique ethnic, economic, and cultural backgrounds. The model we developed could assist clinicians in assessing the risk for PPH patients and in making rapid decisions. The results indicated that the incidence of hysterectomy in this region was 0.32% (74/23490), accounting for 7.05% (74/1050) of PPH cases; factors such as the number of deliveries and histories of cesarean section, placenta previa, uterine atony, and placenta accreta were closely related to the need for hysterectomy following PPH. The prediction model built on these factors showed an AUC of 0.953 (95%CI: 0.928–0.978), with a sensitivity of 90.50% and specificity of 90.70%. It demonstrated good predictive performance, providing a novel tool for predicting hysterectomy in the region and offering fresh insights into implementing individualized intervention measures.

Other studies have shown both similarities and differences to this research. For instance, one study[17] indicated that only 1.6% of women with severe PPH underwent hysterectomy (42/2621), with a maternal age ≥ 40 years, previous cesarean delivery, multiple pregnancies, and placenta previa being significantly associated with the risk of hysterectomy, and with placental implantation disorders being the most common cause of hemorrhage leading to hysterectomy (52%, 22/42). Another retrospective study in Turkey[18] showed that the main indications for hysterectomy were abnormal placental formation (67.6%), followed by uterine atony (28.1%) and uterine rupture (4.2%), with cesarean delivery and previous cesarean as the main risk indicators; other risk indicators included older maternal age (≥ 35 years) and multiple pregnancies. A large-scale study in the United States[19] found risk factors associated with hysterectomy, including a history of cesarean delivery with either placenta previa or increta, placenta previa without cesarean history, antepartum hemorrhage, or placental abruption. Other studies[20-22] have also revealed racial and regional differences, emphasizing the implementation of customized emergency plans in different regions and among different ethnic groups.

The subjects of the study were parturients from the minority regions of Qiandongnan, China. We hypothesized that the genetic qualities of minorities might directly affect the incidence of intractable PPH, while their traditional childbirth views, ethnic cultural backgrounds, education levels, economic conditions, and childbirth service capabilities in the region might impact PPH risk management and decision-making. Emergency hysterectomy in parturients from the region involves complex social factors.

Although the study provided important insights into predicting and managing PPH in the minority regions of Qiandongnan, China, its limitations include being a single-center study and including a relatively small number of hysterectomy cases. Future research should aim to expand the sample size and study scope to enhance the representativeness of the research findings.

This study successfully developed a predictive model for the risk of requiring a hysterectomy due to intractable PPH in the minority regions of Qiandongnan, China. The developed model demonstrated high predictive accuracy and provided significant decision-making support for clinicians. By identifying risk factors associated with hysterectomy, medical professionals can intervene early in high-risk patients, thereby reducing the severe consequences of PPH. Future studies should address the limitations of this study, delve deeper into the roles of ethnic and regional cultural factors in PPH management, and further validate and refine the predictive model.

| 1. | Wang S, Rexrode KM, Florio AA, Rich-Edwards JW, Chavarro JE. Maternal Mortality in the United States: Trends and Opportunities for Prevention. Annu Rev Med. 2023;74:199-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sitaula S, Basnet T, Agrawal A, Manandhar T, Das D, Shrestha P. Prevalence and risk factors for maternal mortality at a tertiary care centre in Eastern Nepal- retrospective cross sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bienstock JL, Eke AC, Hueppchen NA. Postpartum Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1635-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Patek K, Friedman P. Postpartum Hemorrhage-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Causes. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2023;66:344-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Maswime S, Buchmann E. A systematic review of maternal near miss and mortality due to postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Linde LE, Ebbing C, Moster D, Kessler J, Baghestan E, Gissler M, Rasmussen S. Recurrence of postpartum hemorrhage in relatives: A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:2278-2284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Okunlola O, Raza S, Osasan S, Sethia S, Batool T, Bambhroliya Z, Sandrugu J, Lowe M, Hamid P. Race/Ethnicity as a Risk Factor in the Development of Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Thorough Systematic Review of Disparity in the Relationship Between Pregnancy and the Rate of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Cureus. 2022;14:e26460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tsolakidis D, Zouzoulas D, Pados G. Pregnancy-Related Hysterectomy for Peripartum Hemorrhage: A Literature Narrative Review of the Diagnosis, Management, and Techniques. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:9958073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Office of the People's Government of Qiandongnan Prefecture. Introduction to Qiandongnan Prefecture. Qiandongnan Prefecture People's Government website. Available from: http://www.qdn.gov.cn/ztzl_5872570/qdnzqylyzsxm_5882991/qdnzjj_5883000/202303/t20230328_78787397.html. |

| 10. | Obstetrics Subgroup; Chinese Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Perinatal Medicine, Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines for prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage (2023)]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2023;58:401-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hwang DS, Myers L. Management of Postpartum Hemorrhage: Recommendations From FIGO. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:438-440. [PubMed] |

| 12. | FIGO PPH Technical Working Group; Begum F, Beyeza J, Burke T, Evans C, Hanson C, Lalonde A, Meseret Y, Oguttu M, Varmask P, West F, Wright A. FIGO and the International Confederation of Midwives endorse WHO guidelines on prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022;158 Suppl 1:6-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bogardus MH, Wen T, Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Wright JD, Goffman D, Sheen JJ, D'Alton ME, Friedman AM. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Peripartum Hysterectomy Risk and Outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:999-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Downham Moore AM. Race, class, caste, disability, sterilisation and hysterectomy. Med Humanit. 2023;49:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lawson SM, Chou B, Martin KL, Ryan I, Eke AC, Martin KD. The association between race/ethnicity and peripartum hysterectomy and the risk of perioperative complications. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151:57-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gartner DR, Delamater PL, Hummer RA, Lund JL, Pence BW, Robinson WR. Integrating Surveillance Data to Estimate Race/Ethnicity-specific Hysterectomy Inequalities Among Reproductive-aged Women: Who's at Risk? Epidemiology. 2020;31:385-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pettersen S, Falk RS, Vangen S, Nyfløt LT. Peripartum hysterectomy due to severe postpartum hemorrhage: A hospital-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022;101:819-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vural T, Bayraktar B, Karaca SY, Golbasi C, Odabas O, Taner CE. Indications, risk factors, and outcomes of emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A 7-year retrospective study at a tertiary center in Turkey. Malawi Med J. 2023;35:31-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Corbetta-Rastelli CM, Friedman AM, Sobhani NC, Arditi B, Goffman D, Wen T. Postpartum Hemorrhage Trends and Outcomes in the United States, 2000-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:152-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harvey SV, Pfeiffer RM, Landy R, Wentzensen N, Clarke MA. Trends and predictors of hysterectomy prevalence among women in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:611.e1-611.e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gartner DR, Delamater PL, Hummer RA, Lund JL, Pence BW, Robinson WR. Patterns of black and white hysterectomy incidence among reproductive aged women. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:847-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Meeks M, Voegtline K, Vaught AJ, Lawson SM. Differences in Surgery Classification and Indications for Peripartum Hysterectomy at a Major Academic Institution. m J Perinatol. 2024;41:e623-e629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |