Published online Jul 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4842

Revised: May 23, 2024

Accepted: June 12, 2024

Published online: July 26, 2024

Processing time: 70 Days and 7.3 Hours

Aconitine poisoning is highly prone to causing malignant arrhythmias. The elimination of aconitine from the body takes a considerable amount of time, and during this period, patients are at a significant risk of death due to malignant arrhythmias associated with aconitine poisoning.

A 30-year-old male patient was admitted due to accidental ingestion of aconitine-containing drugs. Upon arrival at the emergency department, the patient intermittently experienced malignant arrhythmias including ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular premature beats, and cardiac arrest. Emer

VA-ECMO can serve as a bridging resuscitation technique for patients with reversible malignant arrhythmias.

Core Tip: A patient poisoned by aconitine was treated with detoxification therapy under Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support and made a full recovery. VA-ECMO can stabilize the hemodynamics of patients poisoned by drugs, providing a therapeutic opportunity for toxin elimination and the recovery of spontaneous cardiac activity and vital signs. We believe that VA-ECMO is an effective method for treating malignant arrhythmias caused by drug poisoning, which can reduce the risk of patient mortality. VA-ECMO is an effective method for treating malignant arrhythmias caused by drug poisoning.

- Citation: Bian YY, Hou J, Khakurel S. Treatment of a patient with aconitine poisoning using veno-arterial membrane oxygenation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(21): 4842-4852

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i21/4842.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4842

Cases of aconitine poisoning are not commonly encountered worldwide, and reports of it causing sudden cardiac death are rare. The treatment principles for aconitine poisoning are not well established. In traditional Chinese medicine, Aconiti Kusnezoffii Radix is commonly used for dispelling wind, relieving pain and dehumidification, but it is highly toxic. Chemical and pharmacological studies have shown that diester-alkaloids in Aconiti Kusnezoffii Radix are both important effective ingredients and toxic ingredients, mainly including aconitine, hypaconitine and mesaconitine[1]. Aconitine is a highly toxic alkaloid found in several plants of the Aconitum genus, commonly known as monkshood or wolfsbane[2]. Aconitine poisoning occurs when individuals ingest or come into contact with these plants or their derivatives[3]. Aconitine often affects myocardial cell function by acting on sodium channels, leading to arrhythmias, tachycardia, and potentially fatal ventricular fibrillation[3]. These effects can result in cardiovascular collapse and sudden death. In severe cases of aconitine poisoning, respiratory paralysis may occur due to its toxic effects on the nerves controlling the respiratory muscles, leading to respiratory failure and death. Current treatment for aconitine poisoning involves gastric lavage for toxin removal, administration of antiarrhythmic drugs, and symptomatic supportive care such as mechanical ventilation[4]. In this patient, veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) support was provided alongside gastric lavage, blood purification, and respiratory support, aiming to prevent recurrent malignant arrhythmias leading to death or irreversible brain damage before toxin removal could be achieved.

The patient, a 30-year-old male, presented to the emergency department six hours after ingesting Chinese herbal medicine.

He mistakenly ingested topical herbal medicine, subsequently experiencing dizziness, nausea, vomiting, numbness, and weakness in the limbs.

Besides a history of hemorrhoids, he had no other medical history.

Besides a history of hemorrhoids, he had no other personal, or family history.

Blood pressure was 103/64 mmHg, pulse was 78 beats/min, body temperature was 37 °C, respiratory rate as 20 breaths/min, and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation was 95%. No obvious abnormalities were found on cardiac, pulmonary, or abdominal examinations.

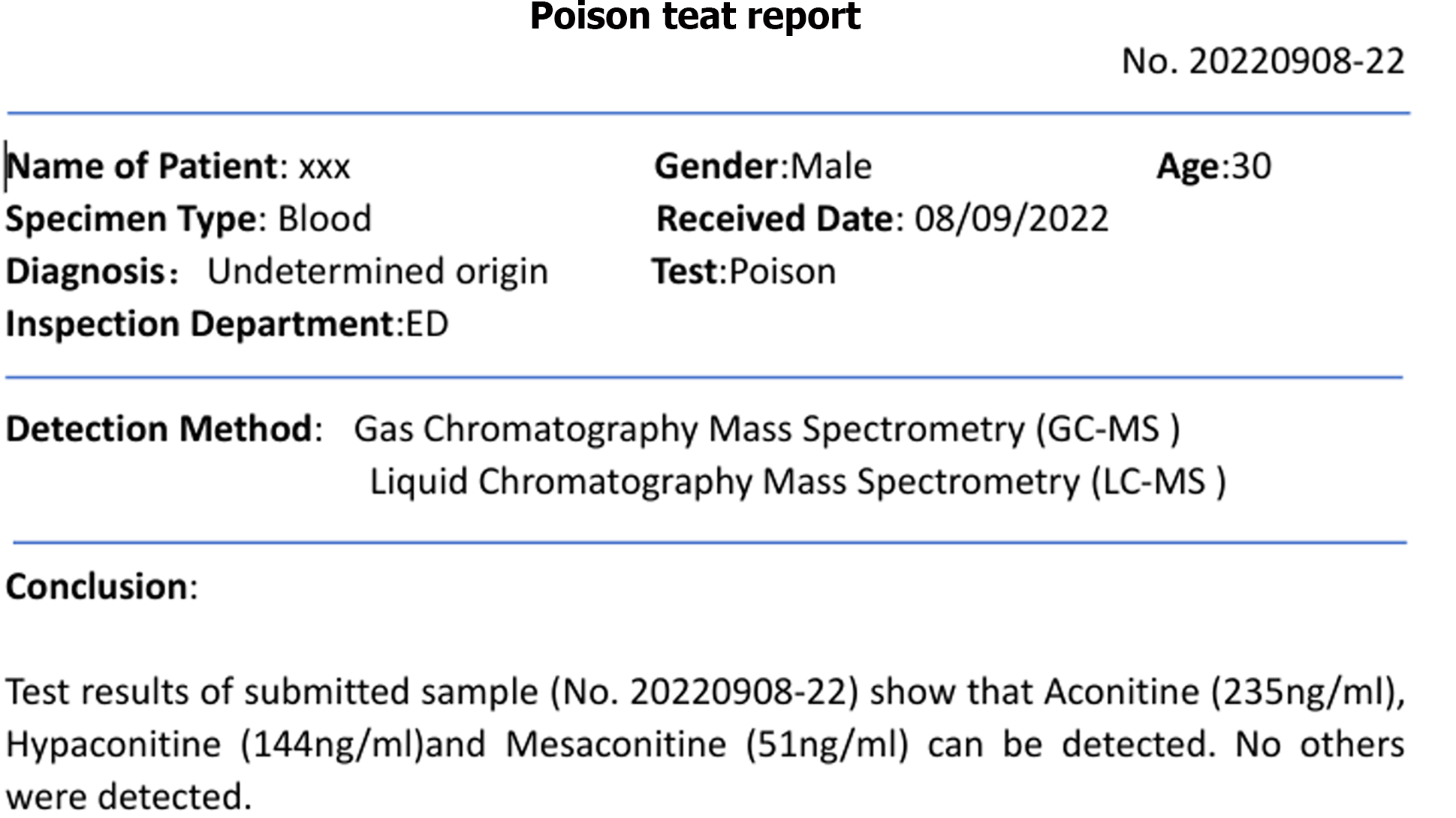

Aconitine poisoning was suspected upon arrival in the emergency department (aconitine in the blood was detected by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry), the herbal medicine contained aconitine; toxin levels measured four hours later were reported as follows: Aconitine 235 ng/mL, hypaconitine 144 ng/mL, mesaconitine 51 ng/mL).

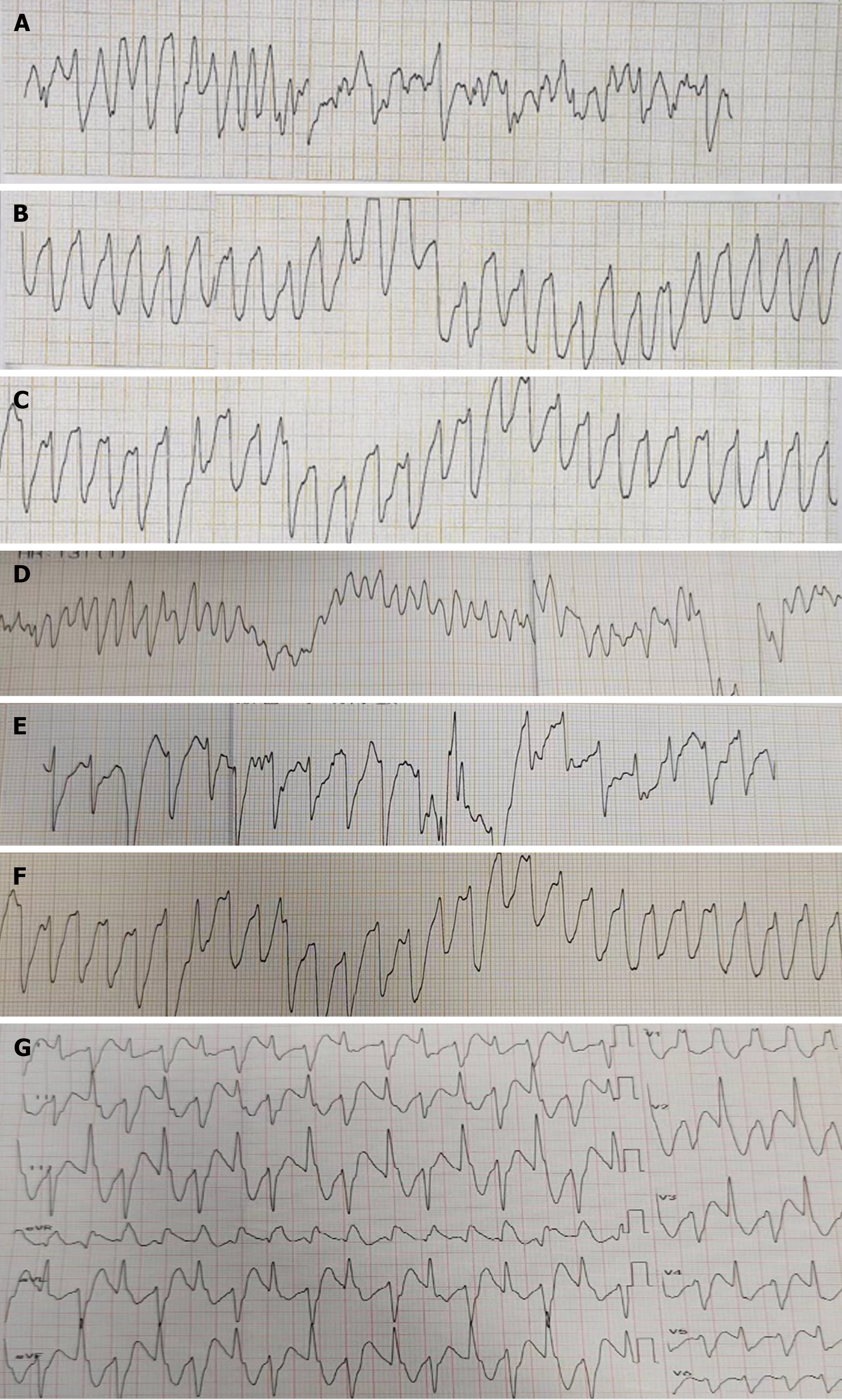

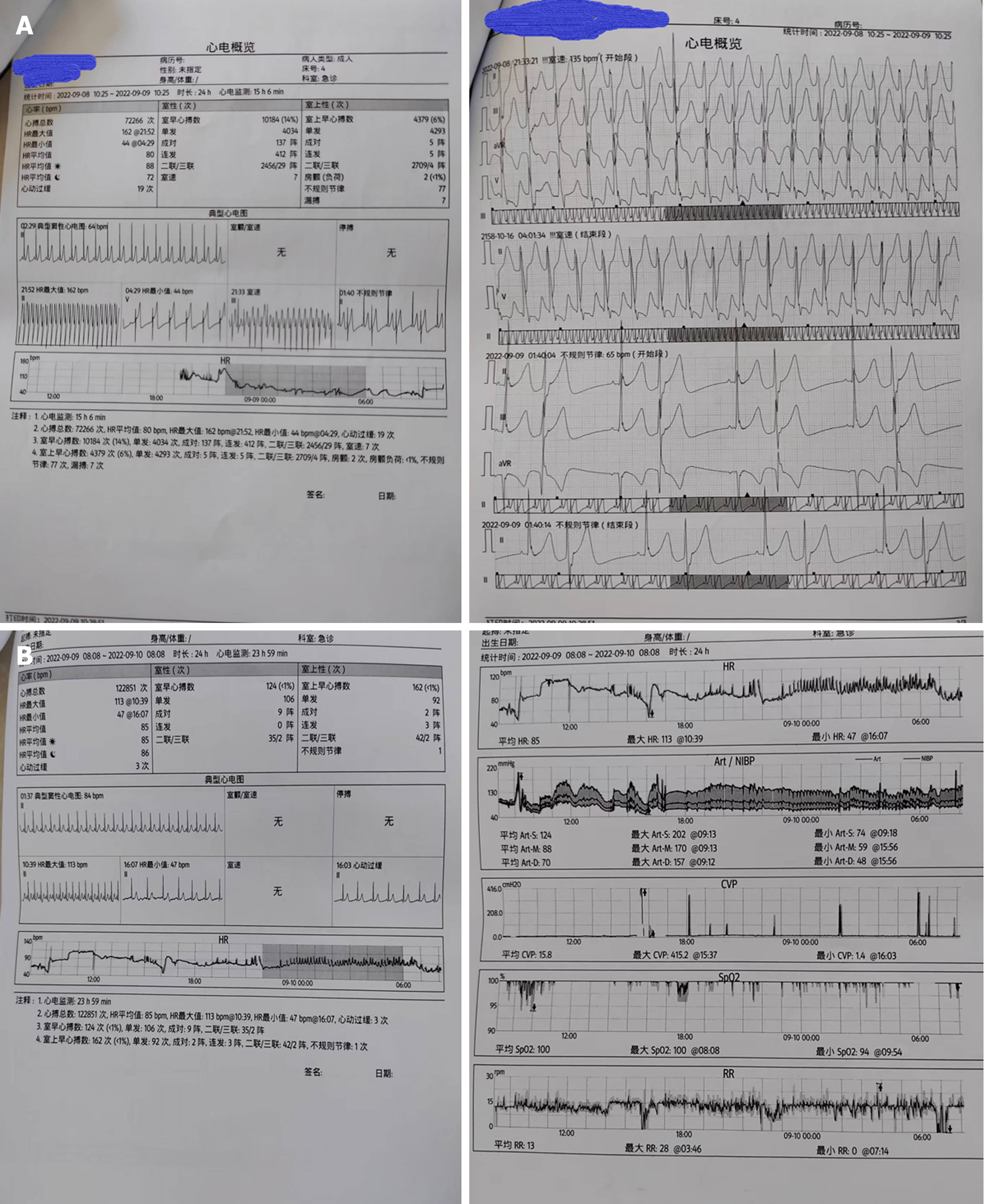

Electrocardiogram, toxic substance detection reports, examination results, and other data are presented in Figures 1-3.

The patient received multidisciplinary treatment from the vascular surgery, cardiology, emergency medicine, and critical care departments.

Aconitine poisoning.

VA-ECMO is a critical therapy that offers simultaneous respiratory and cardiac assistance, generally used in the fields of heart failure, myocarditis, pulmonary embolism, post-cardiac surgery, and heart transplantation[5].

Prescription Dose 35 mL/kg/h, blood flow rate 150 mL/min, replacement fluid rate 1225 mL/h, dialysis fluid rate 1225 mL/h, sodium bicarbonate 81 mL/h, calcium gluconate 8 mL/h, target balance volume 0 mL/h, ultrafiltration rate: 81 + X (X is adjusted by the nurse based on the hourly infusion volume of fluid). Hemoperfusion is performed using the HA380.

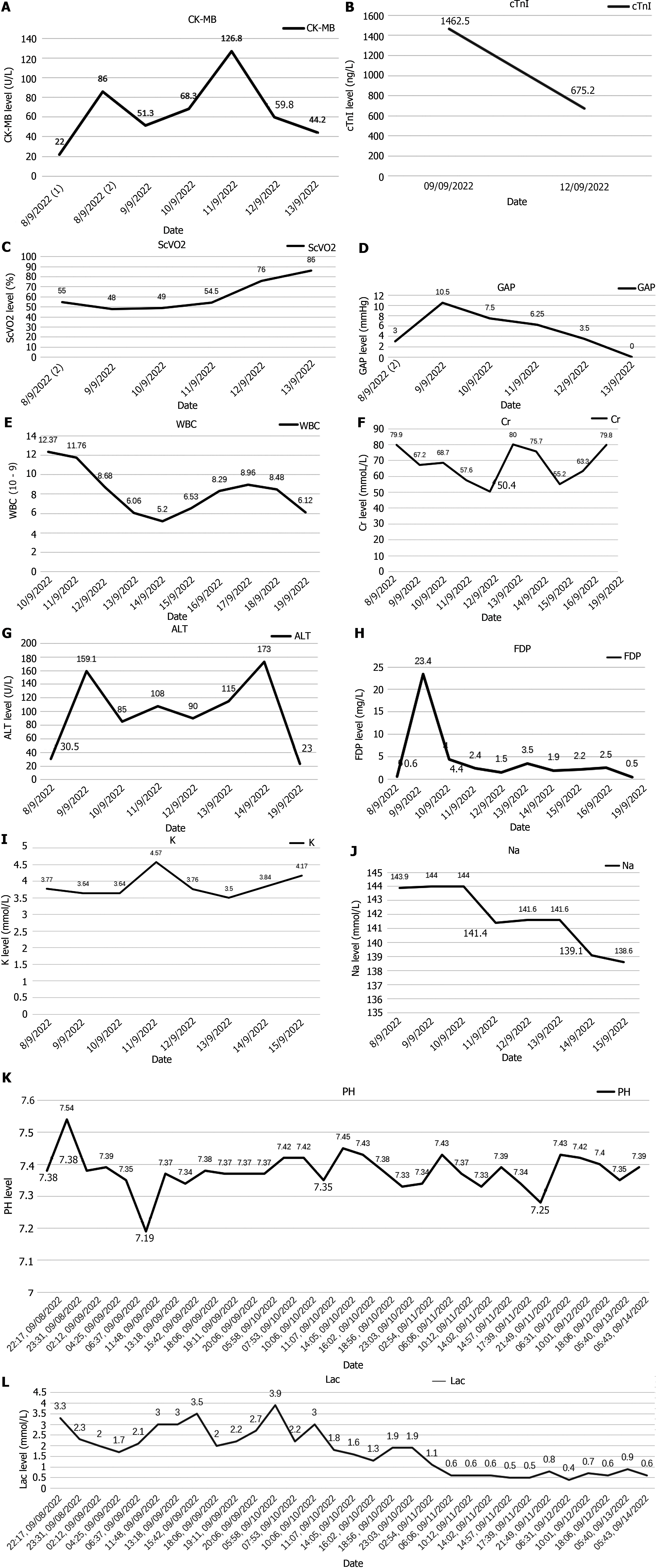

Gastric lavage and fluid resuscitation were initiated. Approximately 1.5 h after arrival in the emergency room, the patient developed ventricular tachycardia, followed by ventricular fibrillation and loss of consciousness. Arterial pulsation disappeared, and blood pressure became unmeasurable. Immediate treatment included defibrillation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, adrenaline, amiodarone, and endotracheal intubation for assisted ventilation. After thirty minutes of resuscitation, the patient reverted to sinus rhythm, with subsequent occurrences of ventricular ectopic beats and couplets. Ventricular fibrillation intermittently recurred, with intermittent defibrillation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation administered (during which toxin analysis results were obtained, as shown in Figure 4). Considering that the patient had refractory arrhythmia and was at risk of recurrent cardiac arrest, the use of VA-ECMO was indicated for supportive treatment. We therefore decided to administer VA-ECMO treatment. The ECMO team determined the indication for VA-ECMO support. Three hours after presentation to the emergency department, a 17F cannula was inserted via the right femoral artery, and a 21F cannula was inserted via the femoral vein. VA-ECMO was successfully established, stabilizing blood pressure and limb perfusion status. The patient was transferred to the Emergency Intensive Care Unit (EICU). Aconitine is a lipophilic drug that quickly enters tissues and organs such as the heart. Hemoperfusion can effectively clear lipophilic drugs[3]. The present patient had repeatedly experienced cardiac arrest, which suggested a cascade reaction of inflammatory factors. We thought that it was necessary to provide the patient with volume manage

| 19:00 September 8, 2022 | 20:00 September 8, 2022 | 20:30 September 8, 2022 | 21:00 September 8, 2022 | 22:00 September 8, 2022 | 22:31 September 8, 2022 | 22:41 September 8, 2022 | 23:00 September 8, 2022 | |

| ECMO rotational speed (r/min) | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2800 |

| Flow rate (L/min) | 1.02 | 1.03 | - | 1.50 | 1.92 | 1.01 | - | 2.72 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 138 | 142 | 138 | 142 | 106 | 132 | 73 | 84 |

| Cardiac rhythm | Sinus rhythm | Ventricular tachycardia | Ventricular tachycardia | Ventricular tachycardia | Sinus rhythm | Ventricular tachycardia | Sinus rhythm | - |

| Invasive arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | 142/90 | 132/82 | - | 146/89 | 106/92 | - | - | 100/81 |

| Cardiac ultrasound | - | - | - | - | - | Electromechanical dissociation | - | No apparent effective contractions |

| 9:00 September 9, 2022 | 10:00 September 9, 2022 | 12:00 September 9, 2022 | 13:00 September 9, 2022 | 16:00 September 9, 2022 | 17:00 September 9, 2022 | 16:00 September 10, 2022 | 7:00 September 11, 2022 | 8:00 September 11, 2022 | |

| ECMO rotational speed (r/min) | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 | 1800 | 1700 | 1500 | 1200 |

| Flow rate (L/min) | 2.47 | 2.37 | 2.54 | 2.21 | 2.50 | 1.42 | 1.62 | 1.59 | 1.10 |

| 47 | 151 | 105 | 97 | 50 | 87 | 64 | 104 | 65 | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | Sinus bradycardia | Atrial fibrillation | Sinus tachycardia | Sinus rhythm | Ventricular bradycardia | Sinus rhythm | Ventricular tachycardia | Sinus rhythm | - |

| 80/47 | 82/58 | 139/91 | 142/81 | 83/55 | 111/61 | 127/67 | 144/68 | 99/55 | |

| Cardiac rhythm | Weak cardiac contractions | No apparent effective contractions | No apparent effective contractions | Mild recovery of cardiac contractions | No apparent effective contractions | Cardiac contractility recovery | Cardiac contractility recovery | Cardiac contractility recovery | Cardiac contractility recovery |

He was transferred to a general ward and received symptomatic treatment, including rehabilitation and nutritional support. The patient was discharged seven days later. Additionally, creatine kinase-MB, lactic acid, Venous-Arterial Carbon Dioxide Partial Pressure Difference, and Central Venous Oxygen Saturation SCVO2 indicators were monitored for four days, with data shown in Figure 4.

Aconitine poisoning is relatively rare clinically. The symptoms of aconite poisoning include paresthesia, nausea, and sweating, followed by abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and then skeletal muscle paralysis, which typically occurs approximately 20 minutes to 2 h after the oral administration of aconitine[8]. Arrhythmia and neurological symptoms are common clinical manifestations of aconitine poisoning[8,9], but they are not specific and there are very few relevant studies. The mortality rate of aconitine poisoning is very high[10]. The identification and diagnosis of this disease are not difficult, but the impact of aconitine on cardiac rhythm makes treatment more difficult. Aconitine exerts its toxic effects mainly by interfering with Na+, Ca2+, and K+ channels in the nervous system[11,12]. It binds to voltage-gated sodium channels present on nerve cell membranes, especially in the heart and muscle systems[13]. Aconitine binds to sodium channels in an open or inactive state, prolonging their activation time, resulting in sustained depolarization of the cell membrane and sustained discharge of action potentials. Prolonged activation of sodium channels results in the excessive release of excitatory neurotransmitters (such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and dopamine), which can affect cardiac muscle cells and cause arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), tachycardia (excessive rapid heartbeats) and potentially fatal ventricular fibrillation, and these effects may lead to cardiovascular failure and sudden death[14]. Activation of sodium channels can also overstimulate nerve cells, produce toxic effects on the nerves that control respiratory muscles, cause respiratory paralysis, and can also cause symptoms such as muscle twitching, tremors, and epileptic seizures in skeletal muscles[15]. Ingestion of aconitine-containing plants or preparations can also cause gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea[16]. Respiratory paralysis and skeletal muscle symptoms caused by aconitine poisoning can be controlled by treatments such as mechanical ventilation, analgesia, sedation, and muscle relaxation to provide time for drug metabolism. However, arrhythmias do not give patients much time to wait for the metabolism of toxic substances and often lead to the death of patients due to various malignant arrhythmias. The patient in this case had symptoms such as numbness, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea before admission. After entering the emergency department, he was diagnosed with aconitine poisoning based on his medical history. Toxin analysis was performed and symptomatic treatment such as gastric lavage and rehydration was performed. The patient soon developed a malignant arrhythmia event. There is no specific antidote for aconitine poisoning. Intravenous infusion is routinely given to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance. Drugs such as lidocaine, phenytoin, β-blockers or antiarrhythmic drugs are used under electrocardiographic monitoring to manage abnormal heart rhythms and treatments such as seizure control[17,18]. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation patterns are independently associated with mortality, so it is important to initiate Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation before physiologic deterioration or cardiac arrest occurs. For patients with severe respiratory and circulatory failure, VA-ECMO can effectively improve tissue perfusion and provide patients with a time window for surgery or other treatments for the original disease[19]. It provides patients with the opportunity to undergo surgery or cardiac recovery. Currently, ECMO is widely used in the rescue treatment of cardiac arrest patients. Early use of ECMO may have a good therapeutic effect in stabilizing circulation and maintaining organ function in patients with reversible malignant arrhythmias. The next step is to continue to confirm the efficacy of ECMO in patients with aconitine poisoning through extensive multicenter prospective trials. Blood purification technology is used to shorten the retention time of poisons and reduce the impact of poisons on sodium channels. However, the elimination of aconitine takes time, and it is extremely important to maintain organ perfusion during this period. Current drugs such as lidocaine or phenytoin can be used to stabilize the cardiac membrane and reduce the risk of arrhythmia, but the effect is unclear. Patients with aconitine poisoning have coexisting fast and slow arrhythmias, and beta blockers are required. Use is on an individual basis under close supervision. With the popularity of ECMO technology, ECMO emergency teams can provide immediate support in life-threatening emergencies to improve circulation status in the shortest possible time.

Our experience proves that VA-ECMO is a feasible treatment option for reversible malignant arrhythmias caused by drug poisoning. Extracorporeal life support is an effective method for drug poisoning and is worth exploring.

We would like to acknowledge the hard and dedicated work of all the staff who implemented the intervention and evaluation of the study.

| 1. | Gao Y, Fan H, Nie A, Yang K, Xing H, Gao Z, Yang L, Wang Z, Zhang L. Aconitine: A review of its pharmacokinetics, pharmacology, toxicology and detoxification. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;293:115270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chan YT, Wang N, Feng Y. The toxicology and detoxification of Aconitum: traditional and modern views. Chin Med. 2021;16:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Zhang D, Lv J, Zhang B, Zhang X, Jiang H, Lin Z. The characteristics and regularities of cardiac adverse drug reactions induced by Chinese materia medica: A bibliometric research and association rules analysis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;252:112582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Nyirimigabo E, Xu Y, Li Y, Wang Y, Agyemang K, Zhang Y. A review on phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology studies of Aconitum. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;67:1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Vyas A, Bishop MA. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Adults. 2023 Jun 21. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zhang L, Miao X, Li Y, Hu F, Ma D, Zhang Z, Sun Q, Zhu Y, Zhu Q. Traditional processing, uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicology of Aconitum sinomontanum Nakai: A comprehensive review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;293:115317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lim CC, Tan HK. An Introduction to Extracorporeal Blood Purification in Critical Illness. Proc Singap Healthc. 2012;21:109-119. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mi L, Li YC, Sun MR, Zhang PL, Li Y, Yang H. A systematic review of pharmacological activities, toxicological mechanisms and pharmacokinetic studies on Aconitum alkaloids. Chin J Nat Med. 2021;19:505-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alalmay A, Al Bashabshe A, Al Shamrani N, Othman LB, Alfaifi M, Algarni Y, Awwadh A, Alhanash A, Ogran H, Sinnah K, El Razzaz M. Aconite Poisoning with Good Outcome, Case Study and Literature Review. CRCM. 2020;9:217-222. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Chan TY. Aconite poisoning. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009;47:279-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yang C, Zeng X, Cheng Z, Zhu J, Fu Y. Aconitine Induces TRPV2-Mediated Ca(2+) Influx through the p38 MAPK Signal and Promotes Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021;2021:9567056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang H, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang X, Meng X. An Updated Meta-Analysis Based on the Preclinical Evidence of Mechanism of Aconitine-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:900842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pan MC, Zhou XW, Liu Y, Wang YN, Qiu XG, Wu SF, Liu Q. [Research Progress on the Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicology of Ethanol-Aconitine Induced Arrhythmia]. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;36:115-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhou W, Liu H, Qiu LZ, Yue LX, Zhang GJ, Deng HF, Ni YH, Gao Y. Cardiac efficacy and toxicity of aconitine: A new frontier for the ancient poison. Med Res Rev. 2021;41:1798-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gao X, Hu J, Zhang X, Zuo Y, Wang Y, Zhu S. Research progress of aconitine toxicity and forensic analysis of aconitine poisoning. Forensic Sci Res. 2020;5:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mahon MB, Sack A, Aleuy OA, Barbera C, Brown E, Buelow H, Civitello DJ, Cohen JM, de Wit LA, Forstchen M, Halliday FW, Heffernan P, Knutie SA, Korotasz A, Larson JG, Rumschlag SL, Selland E, Shepack A, Vincent N, Rohr JR. A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease. Nature. 2024;629:830-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | da Silva LC, Pessoa DA, Lopes JR, de Albuquerque LG, da Silva LS, Garino Junior F, Riet-Correa F. Protection against Amorimia septentrionalis poisoning in goats by the continuous administration of sodium monofluoroacetate-degrading bacteria. Toxicon. 2016;111:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | McCabe MD, Cervantes R, Kewcharoen J, Sran J, Garg J. Quelling the Storm: A Review of the Management of Electrical Storm. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37:1776-1784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Russo JJ, Del Sorbo L. VA-ECMO When All Seems Lost: Defining the Right Person, Place, and Time. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:910-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |