Published online Jul 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4703

Revised: May 14, 2024

Accepted: June 7, 2024

Published online: July 26, 2024

Processing time: 88 Days and 3.4 Hours

The benefits and risks of Xileisan (XLS) in the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) remain unclear.

The present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combination of XLS and mesalazine when treating UC.

We searched eight databases for clinical trials evaluating the combination of XLS and mesalazine in the treatment of UC, up to January 2024. Meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis (TSA) were performed using Revman 5.3 and TSA 0.9.5.10 beta, respectively.

The present study included 13 clinical studies involving 990 patients, of which 501 patients received XLS combined with mesalazine while 489 patients received mesalazine alone. The meta-analysis showed that, in terms of efficacy, the com

Treatment with XLS alleviated the clinical symptoms, intestinal mucosal injury, and inflammatory response in patients with UC, while demonstrating good safety.

Core Tip: The benefits and potential risks of Xileisan (XLS) in the treatment of ulcerative colitis (UC) remain unclear. The present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of XLS combined with mesalazine in the treatment of UC through meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. The meta-analysis showed that XLS alleviated the clinical symptoms, intestinal mucosal injury, and inflammatory response in patients with UC, while demonstrating good safety. XLS, therefore, represents a safe and effective treatment strategy for UC.

- Citation: Yang XY, Yu YF, Tong KK, Hu G, Yu R, Su LJ. Efficacy and safety of Xileisan combined with mesalazine for ulcerative colitis: A meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(21): 4703-4716

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i21/4703.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4703

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is the chronic idiopathic inflammation of the colonic mucosa caused by immune system dys

Xileisan (XLS) is a classical Chinese patent medicine. According to traditional Chinese medicine theory, XLS has the following effects: Heat-clearance and detoxification, blood activation, pain relief, promotion of pus discharge and tissue regeneration, and putrefaction elimination[9]. In clinical practice in China, XLS was originally used to treat oral ulcers, but later became widely used for the treatment of mucosal inflammatory diseases[10]. XLS has been reported to reduce inflammation in the intestinal mucosa, and its efficacy in treating mild UC is comparable to that of mesalazine, suggesting its potential as a complementary treatment for UC[11]. Due to a lack of high-quality evidence, however, the specific benefits and potential risks of XLS in the treatment of UC remain unclear. The present study, therefore, aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the combination of XLS and mesalazine in treating UC through a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis (TSA), and to provide evidence for the clinical applications of XLS.

The protocol for the present meta-analysis and TSA was registered in PROSPERO (No. CRD42024501208). We conducted a literature search on UC with XLS, using a strategy that integrated subject terms and expanded keywords. The subject terms used were “Xileisan” and “ulcerative colitis,” and expanded keywords were obtained from Medical Subject Headings and Sinomed. We searched the following public databases from the inception of each database until January 2024: The China National Knowledge Internet; Wanfang Data; China Science and Technology Journal Database; Sinomed; EMBASE; PubMed; the Cochrane Library; and Web of Science. The search was conducted without any language or other specified restrictions.

The inclusion criteria were as follows, based on the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study stru

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Reviews, animal experiments, or case reports, etc.; (2) duplicate publications; and (3) studies with incomplete data.

After importing all the search results into Endnote X9, the irrelevant articles were eliminated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine the included literature.

The included literature was categorized and organized, and basic information, such as author(s), publication year, sample size, mean age, sex ratio, intervention measures, and duration of treatment was extracted.

The risk of bias for each study was assessed according to the methods specified in the Cochrane guidelines. These tasks were conducted independently by the two researchers, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third researcher.

Meta-analysis: Revman 5.3 was used for the meta-analysis. The I2 test was used to analyze the heterogeneity among the included studies, with I2 < 50% indicating low heterogeneity, for which a fixed-effects model was used for the analysis, while I2 ≥ 50% indicated high heterogeneity, for which a random-effects model was used for the analysis. Risk ratio (RR) and 95%CI were used as the effect size for dichotomous variables, while mean difference (MD) and 95%CI were used as the effect size for continuous variables. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Sensitivity analysis: A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was used to assess the robustness of the meta-analysis results as follows: One study at a time was excluded while the remaining studies were combined in each analysis. The results were considered robust if there was no significant change in the combined effect size due to the absence of one study.

TSA: TSA 0.9.5.10 was used for the TSA, a cumulative meta-analysis method that prevents erroneous conclusions due to an insufficient sample size by controlling for random errors in a study. The TSA assessed whether the results of the current meta-analysis were conclusive based on the variability and sample size of the data, with type I and II errors set at 5% and 20%, respectively. When the Z-value curve crossed the boundary, the results of the meta-analysis were consi

Publication bias assessment: Stata 15.0 was used for the publication bias assessment. Harbord’s test is a method for assessing publication bias in meta-analyses, and is particularly suitable for dealing with data involving dichotomous variables. It detects publication bias on the basis of the relationship between the effect size of an outcome and its standard error. A P value > 0.1 for Harbord regression suggests that there is no significant publication bias.

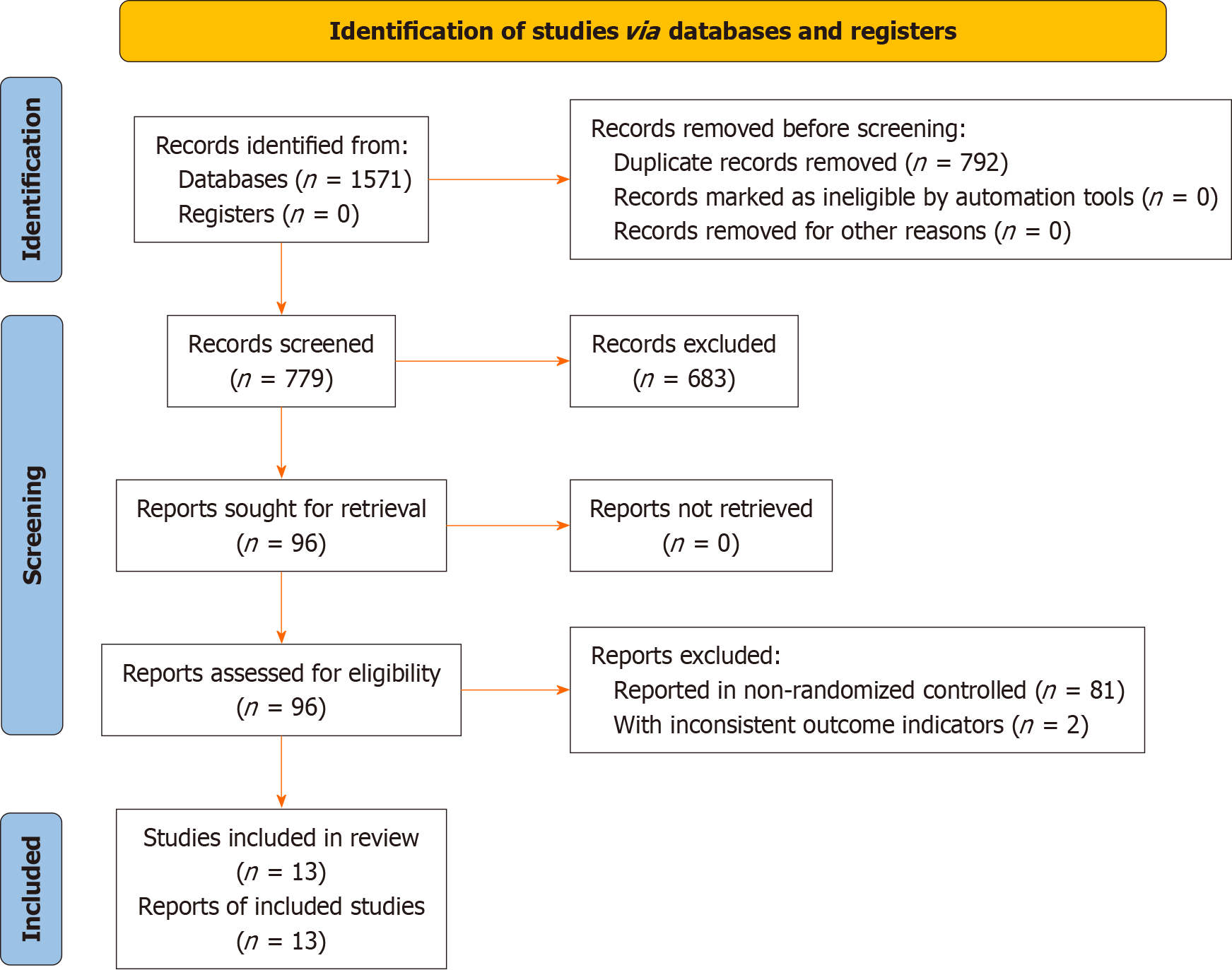

A total of 1571 articles were initially obtained through the literature search, of which 792 articles were excluded as duplicates and 766 because they did not meet the selection criteria. In total, 13 articles[13-25] were included in the present analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

The 13 included articles[13-25] referenced a total of 990 patients, among which 501 were treated with acombination of XLS and mesalazine, and 489 mesalazine alone. The publication dates of the included studies ranged from 2009 to 2022, and all study centers were located in China, as shown in Table 1.

| Ref. | Sample size | Age (years) | Male | Disease duration (years) | Intervention | Treatment duration (weeks) |

| Cai et al[13], 2022 | 38 | 30.2 | 44.7 | 3.0 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 8 |

| 38 | 30.2 | 50.0 | 3.0 | Mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 8 | |

| Ding et al[14], 2019 | 27 | 62.3 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | ||

| 26 | 62.3 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | |||

| Ge et al[15], 2011 | 30 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | |||

| 30 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | ||||

| Li et al[16], 2017 | 50 | 72.8 | 56.0 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 8 | |

| 50 | 60.8 | 58.0 | Mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 8 | ||

| Liu et al[17], 2015 | 30 | 38.9 | 46.7 | XLS 2.0 g/d, mesalazine 1.0 g/d | 8 | |

| 26 | 37.4 | 42.3 | Mesalazine 1.0 g/d | 8 | ||

| Ni et al[18], 2011 | 30 | 53.6 | 80.0 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 1.25-1.75 g/d | 4 | |

| 30 | 50.8 | 73.3 | Mesalazine 1.25-1.75 g/d | 4 | ||

| Wang et al[19], 2016 | 58 | 25.6 | 55.1 | 3.6 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 3 |

| 58 | 26.5 | 60.3 | 3.2 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 3 | |

| Xu et al[20], 2010 | 42 | 38.4 | 69.0 | 5.1 | XLS 2.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 |

| 42 | 59.5 | 6.5 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | ||

| Yao et al[21], 2022 | 30 | 50.2 | 50.0 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 4 | |

| 30 | 49.7 | 53.3 | Mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 4 | ||

| Zhang et al[22], 2013 | 35 | 35.3 | 62.9 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 2 | |

| 35 | 35.8 | 60.0 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 2 | ||

| Zhang et al[23], 2016 | 45 | 37.3 | 51.1 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 3 | |

| 45 | 36.2 | 55.6 | Mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 3 | ||

| Zhu et al[24], 2013 | 58 | 45.5 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 4 | ||

| 52 | 45.5 | Mesalazine 3.0 g/d | 4 | |||

| Zhu et al[25], 2009 | 28 | XLS 1.0 g/d, mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 | |||

| 27 | Mesalazine 4.0 g/d | 4 |

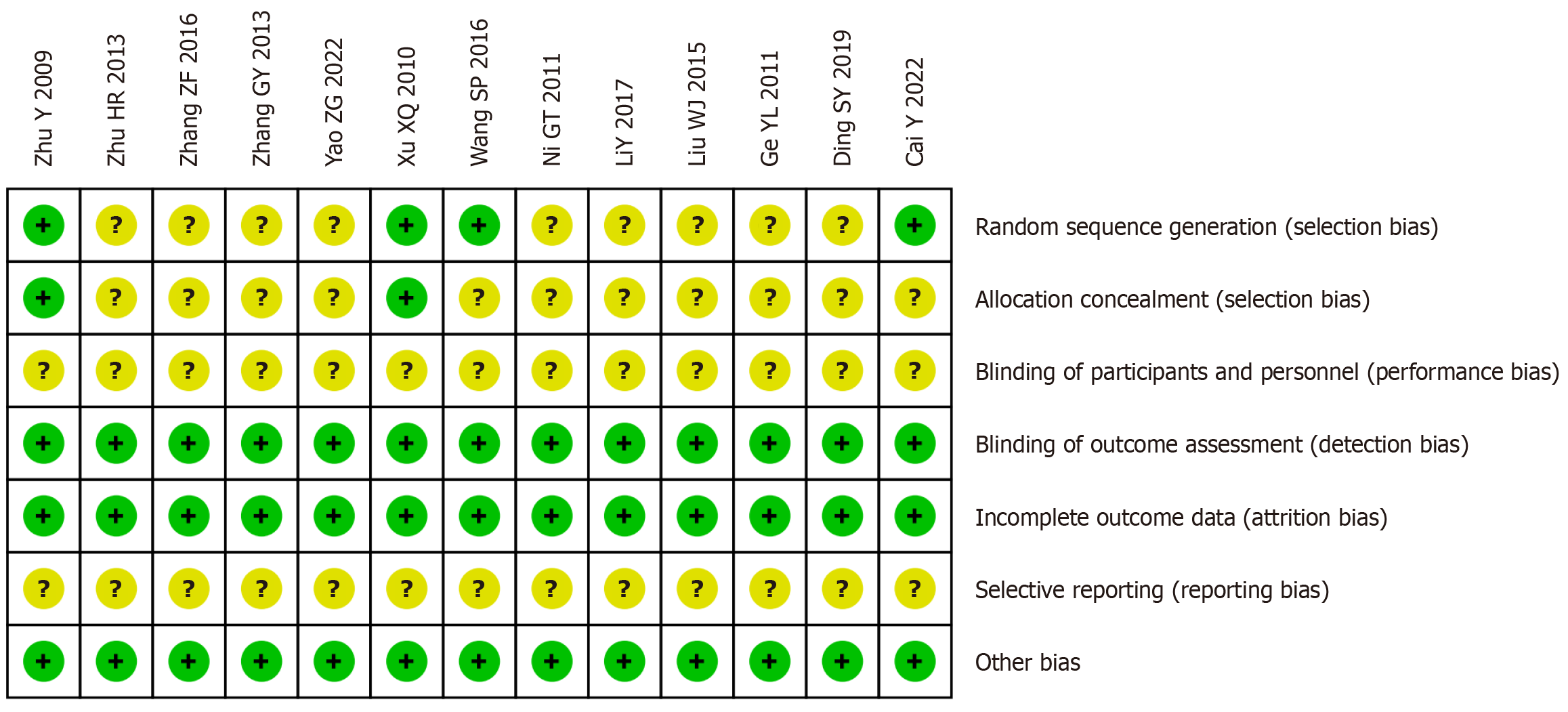

Among the 13 included clinical studies, 9 did not clearly specify the randomization method, 11 did not clearly specify the allocation concealment, and 13 did not clearly specify the blinding of interventions to participants and selective reporting. The remaining domains had low risks of bias, as shown in Figure 2.

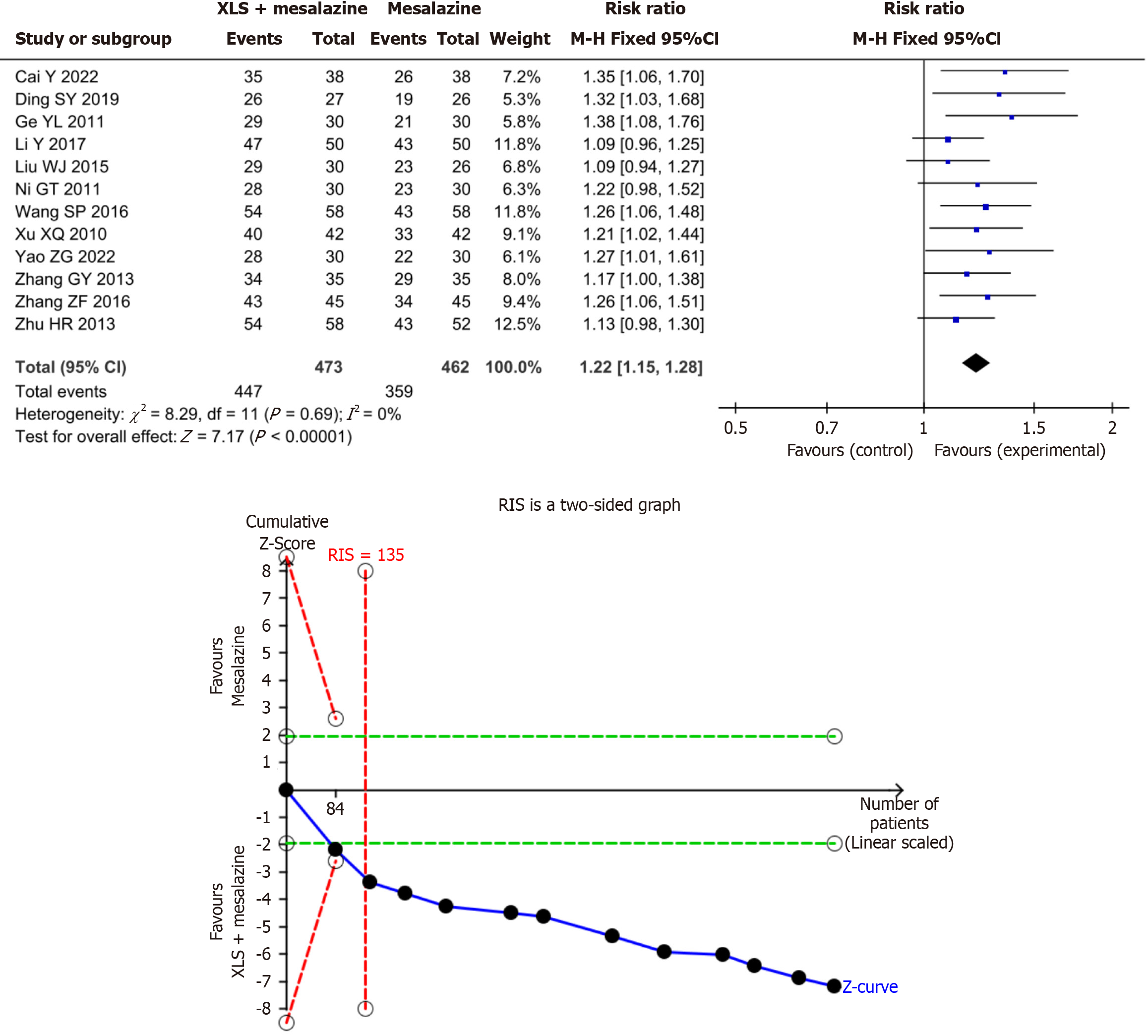

Clinical efficacy rate: The results of the present meta-analysis showed that the combination of XLS and mesalazine significantly improved the clinical efficacy rate–by 22% compared to mesalazine alone (RR = 1.22; 95%CI: 1.15–1.28; P < 0.00001). The results of the present TSA indicated conclusiveness in the meta-analysis results regarding the clinical efficacy rate, as shown in Figure 3.

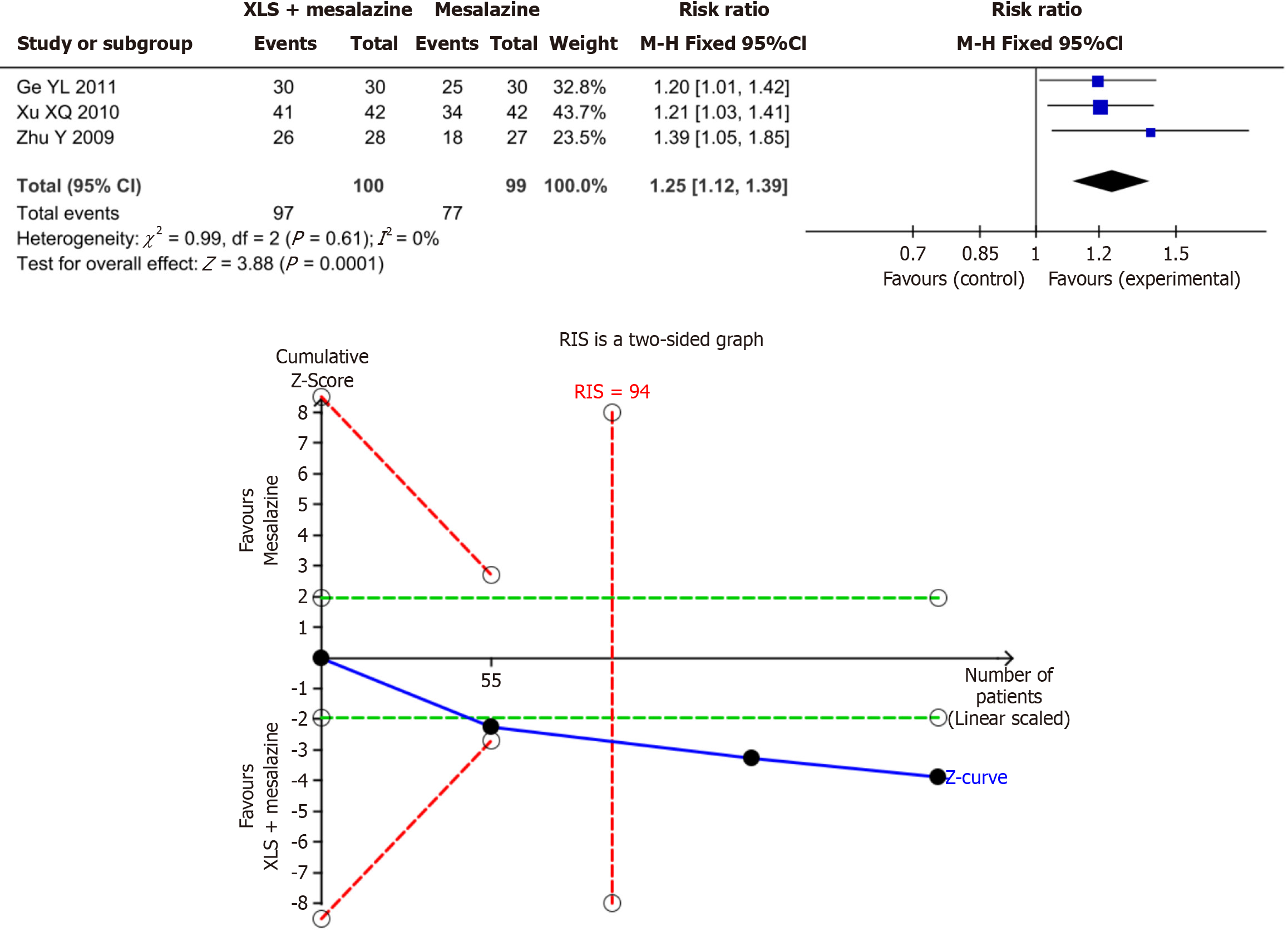

Mucosal improvement rate: The results of the present meta-analysis revealed that the combination of XLS and mesalazine significantly increased the mucosal improvement rate–by 25% compared to mesalazine alone (RR = 1.25; 95%CI: 1.12–1.39; P = 0.0001). The results of the present TSA indicated conclusiveness in the meta-analysis results for the mucosal improvement rate, as shown in Figure 4.

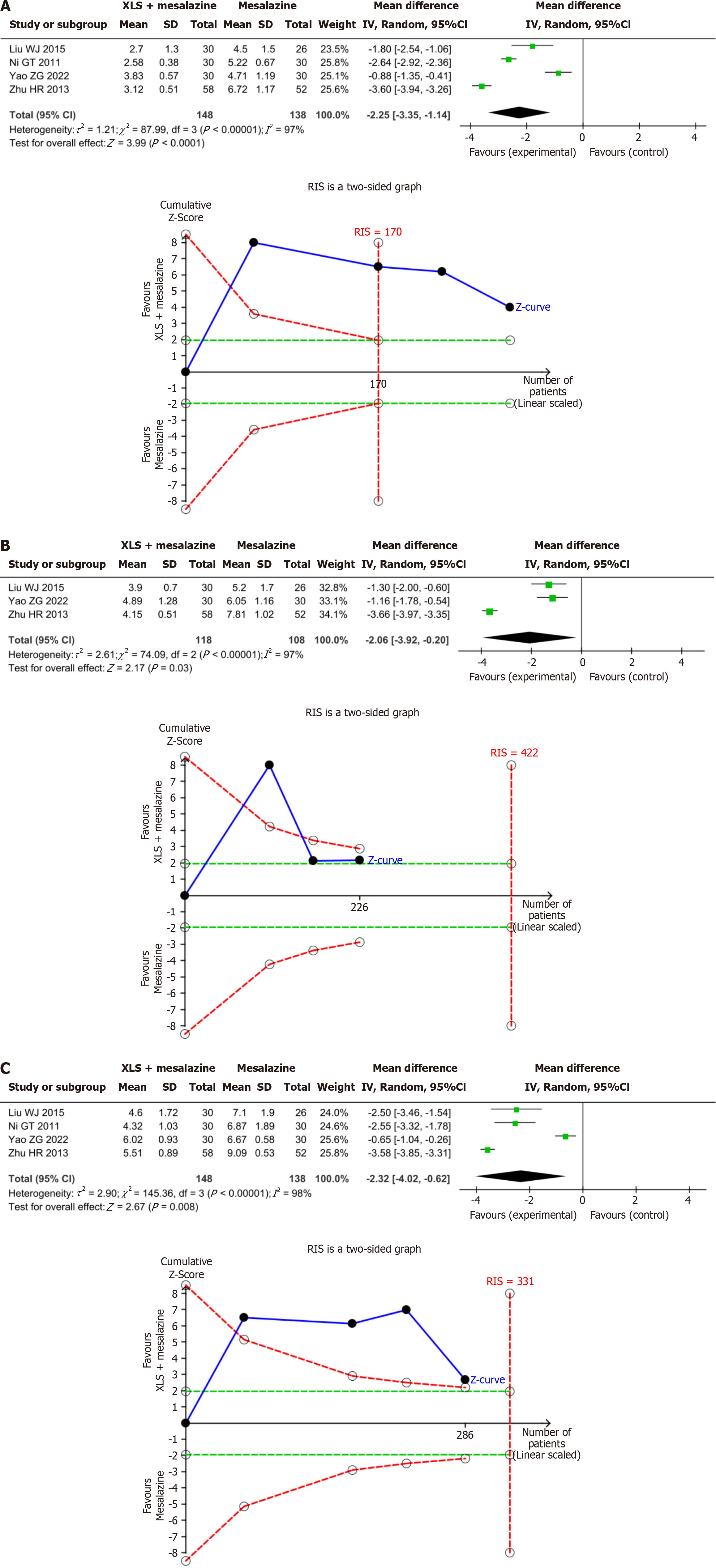

Duration of symptoms: The results of the present meta-analysis demonstrated that the combination of XLS and mesalazine significantly shortened the duration of abdominal pain, by 2.25 days (MD = -2.25; 95%CI: -3.35 to -1.14; P < 0.0001), diarrhea by 2.06 days (MD = -2.06; 95%CI: -3.92 to -0.20; P = 0.03), and hematochezia by 2.32 days (MD = -2.32; 95%CI: -4.02 to -0.62; P =0.008) compared to mesalazine alone. The results of the present TSA indicated conclusiveness in the meta-analysis results for the duration of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia, as shown in Figure 5.

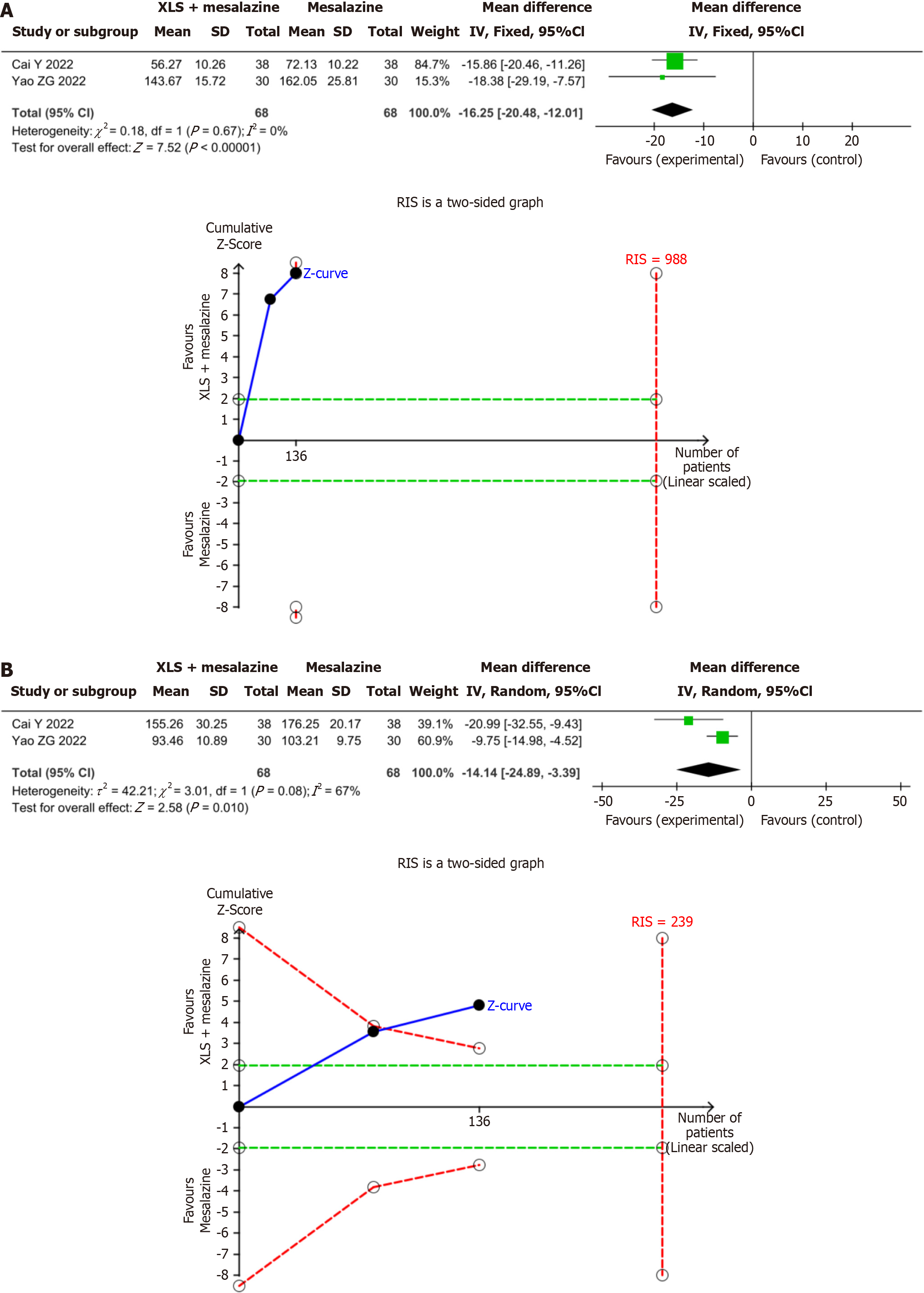

Inflammatory factors: The results of the present meta-analysis showed that the combination of XLS combined and significantly decreased TNF-α levels, by 16.25 ng/mL (MD = -16.25; 95%CI: -20.48 to -12.01; P < 0.00001) and IL-6 levels by 14.14 ng/mL (MD = -14.14; 95%CI: -24.89 to -3.39; P = 0.01) compared to mesalazine alone. The results of the present TSA indicated conclusiveness in the meta-analysis results for TNF-α and IL-6, as shown in Figure 6.

The results of the present meta-analysis showed that the combination of XLS and mesalazine significantly reduced relapse, by 59% (RR = 0.41; 95%CI: 0.22–0.76; P = 0.005) compared to mesalazine alone, while total adverse events (RR = 1.10; 95%CI: 0.61–1.97; P =0.75), gastrointestinal adverse events (RR = 1.08; 95%CI: 0.50–2.36; P = 0.84), abdominal distension (RR =0.99; 95%CI: 0.23–4.22; P = 0.99), and erythema (RR = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.27–3.57; P= 0.98) were comparable. The results of the present TSA indicated conclusiveness in the meta-analysis results of relapse, as shown in Table 2.

| Outcome | Experimental | Control | I2 | RR (95%CI) | P value | TSA |

| Total adverse events | 21/226 | 19/224 | 0 | 1.10 (0.61-1.97) | 0.75 | No |

| Gastrointestinal adverse events | 11/168 | 10/166 | 0 | 1.08 (0.50-2.36) | 0.84 | No |

| Abdominal distension | 3/73 | 3/72 | 0 | 0.99 (0.23-4.22) | 0.99 | No |

| Erythra | 3/130 | 3/128 | 0 | 0.98 (0.27-3.57) | 0.98 | No |

| Relapse | 12/116 | 29/115 | 50 | 0.41 (0.22-0.76) | 0.005 | Yes |

The results of the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis indicated that the meta-analysis results for clinical efficacy and mucosal improvement rates, duration of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia, TNF-α and IL-6 Levels, total and gastrointestinal adverse events, abdominal distension, and erythema were robust. The results for relapse, however, were not found to be robust, due to the study by Wang et al[19]. Once the aforementioned study by Wang et al[19] was removed, the combined result for relapse no longer held significance (RR = 0.36; 95%CI: 0.12–1.05; P = 0.06).

The results of the subgroup analysis showed that in terms of XLS dosage, doses of 1.0 g/d (RR = 1.23; 95%CI: 1.15–1.30; P < 0.00001) and 2.0 g/d (RR = 1.16; 95%CI: 1.03–1.31; P = 0.01) both significantly improved the clinical efficacy rate. When evaluating mesalazine dosage, the combination of XLS with 1.0–2.0 g/d (RR = 1.15; 95%CI: 1.01–1.32; P = 0.04), 3.0 g/d (RR = 1.20; 95%CI: 1.11–1.30; P < 0.00001), and 4.0 g/d (RR = 1.26; 95%CI: 1.15–1.37; P < 0.00001) of mesalazine all significantly improve the clinical efficacy rate. When evaluating treatment duration, XLS treatment for 3 (RR = 1.26; 95%CI: 1.12–1.42; P = 0.0002), 4 (RR 1.23; 95%CI: 1.14–1.34; P < 0.00001), and 8 (RR = 1.16; 95%CI: 1.05–1.29; P = 0.003) weeks all significantly improved the clinical efficacy rate. There was no significant benefit observed, however, with 2 weeks of XLS treatment (RR = 1.17; 95%CI: 1.00–1.38; P = 0.05). The subgroup analysis, therefore, did not find a dose-related difference in the clinical efficacy rate, but did find a treatment duration-related difference, suggesting that a treatment duration ≥ 3 weeks was more effective than 2 weeks, as shown in Table 3.

| Subject | Subgroup | I2 | RR (95%CI) | P value |

| XLS dosage | 1.0 g/d | 0 | 1.23 (1.15-1.30) | < 0.00001 |

| 2.0 g/d | 0 | 1.16 (1.03-1.31) | 0.01 | |

| Mesalazine dosage | 1.0-2.0 g/d | 0 | 1.15 (1.01-1.32) | 0.04 |

| 3.0 g/d | 3 | 1.20 (1.11-1.30) | < 0.00001 | |

| 4.0 g/d | 0 | 1.26 (1.15-1.37) | < 0.00001 | |

| Treatment duration | 2 weeks | 0 | 1.17 (1.00-1.38) | 0.05 |

| 3 weeks | 0 | 1.26 (1.12-1.42) | 0.0002 | |

| 4 weeks | 0 | 1.23 (1.14-1.34) | < 0.00001 | |

| 8 weeks | 33 | 1.16 (1.05-1.29) | 0.003 |

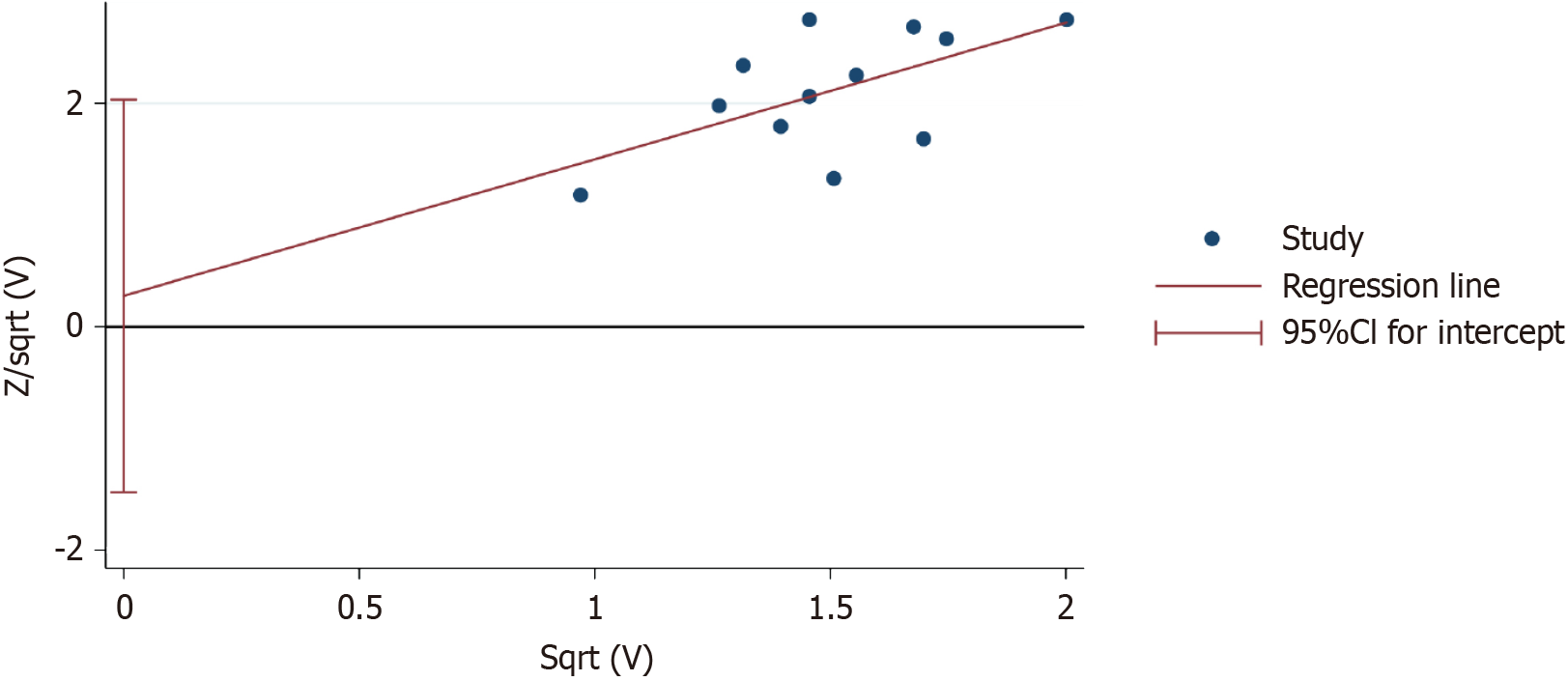

The results of Harbord’s test for the clinical efficacy rate showed P = 0.734, indicating no significant publication bias, as shown in Figure 7.

UC is a recurrent and difficult-to-cure disease that severely affects patients’ quality of life, while also imposing medical and social security costs[26,27]. Unfortunately, the etiology of UC remains unclear; therefore, current clinical manage

Compared to mesalazine alone, the combination of XLS and mesalazine improved the clinical efficacy and mucosal improvement rates by 22% and 25%, respectively, and shortened the duration of abdominal pain by 2.25 days, diarrhea by 2.06 days, hematochezia by 2.32 days. The clinical efficacy rate is a comprehensive indicator for evaluating the relief of clinical symptoms and intestinal mucosal inflammation in patients with UC, while the mucosal improvement rate is an objective indicator for evaluating the condition of the intestinal mucosa[39]. Abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia are the most common clinical symptoms in patients with UC, and are significant factors affecting patients’ quality of life. The benefits of XLS on the clinical efficacy rate, mucosal improvement rate, and duration of symptoms indicate that it promotes the restoration of the normal structure and function of the intestinal mucosa, thereby alleviating clinical symptoms. Relevant studies showed that XLS significantly increased the levels of occludin, claudin-1, and secretory immunoglobulin A, while it decreased β-defensin levels, which may be the mechanism by which it inhibits intestinal inflammation[40]. XLS has also been reported to inhibit endothelial nitric oxide synthase and vascular endothelial growth factor, which may be the mechanism by which it reduces intestinal mucosal bleeding[41]. Additionally, the results of the present meta-analysis showed that XLS significantly reduced TNF-α by 16.25 ng/mL and IL-6 by 14.14 ng/mL. Considering that TNF-α and IL-6 are classic pro-inflammatory factors, the role of XLS in reducing TNF-α and IL-6 further confirms its function in inhibiting intestinal inflammation.

The results of the present subgroup analysis revealed that XLS doses of both 1.0 g/d and 2.0 g/d, when used in combination with mesalazine, significantly improved the clinical efficacy. This results indicates that a dosage range of 1.0–2.0 g/d presents an effective option for clinicians to consider. Additionally, XLS combined with 1.0–2.0 g/d, 3.0 g/d, and 4.0 g/d mesalazine all significantly improved clinical efficacy. This result suggests, therefore, that the additional benefit provided by XLS was not limited by mesalazine dosage. Furthermore, the results of the present analysis showed that treatment with XLS for 3, 4, and 8 weeks significantly improved the clinical efficacy; however, treatment for 2 weeks did not provide significant benefits, indicating that adequate treatment duration may be an important factor in achieving the benefits of XLS. Therefore, we recommend that clinicians ensure an XLS treatment duration of ≥ 3 weeks to ensure that patients achieve optimal benefits.

The combination of XLS and mesalazine, when compared to mesalazine alone, did not increase the total number of adverse events, gastrointestinal adverse events, abdominal distension, or erythema, indicating that the combination of XLS and mesalazine did not increase the risk of adverse events. Additionally, the results of the present study showed a significant, 59%, reduction in relapse with the combination of XLS and mesalazine compared to mesalazine alone, indicating that XLS plays a role in stabilizing conditions and reducing the relapse rate. However, sensitivity analysis revealed that the significance of relapse disappeared after excluding the study by Wang et al[19] suggesting that the benefit of this outcome may be driven that study. Among the three studies included in the analysis of relapse, Wang et al[19] found a benefit in relapse in 116 patients, whereas Ge et al[15] and Zhu et al[25] did not find this benefit in 60 and 55 patients, respectively. The authors speculate, however, that the negative results may be due to an insufficient sample size. The results of the present TSA, therefore, confirmed the aforementioned viewpoint, indicating that the meta-analysis results for relapse, after appropriate adjustments, provide conclusive evidence for the role of XLS in reducing the rate of relapse in patients with UC. This is a positive finding for these patients, as they can maintain relatively good safety while achieving better disease control. However, considering that the results of the present TSA indicated that safety endpoints other than relapse did not reach the desired information value, large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trials are needed to validate the safety of XLS. Furthermore, because of individual variations among patients, it is essential for doctors to conduct further personalized assessments and exercise clinical judgment to determine the most appropriate treatment for each patient.

The present study does have some limitations that need to be noted. First, since XLS is mainly used in the Chinese market, the study samples included are all from China, and research results from other regions and ethnicities are lacking. The authors, therefore recommend establishing research centers in diverse continents and countries in the future to explore the role of XLS in patients with UC of different races. However, as XLS has not yet been listed in other countries, this issue can only be resolved after its approval by the food and drug regulatory authorities in other countries and the studies can be repeated. Second, the overall quality of the included studies was low, and the implementation details of the intervention blinding method were not described, which may increase the risk of implementation bias in the research results. Researchers should develop and execute large-sample, double-blind, randomized controlled trials across multiple centers to provide high-quality evidence for XLS analyses. Third, only two studies reported values for TNF-α and IL-6, which may lead to a decreased accuracy of the research results. The authors recommend, therefore, that future studies focus on the study of blood biochemical indicators to further elucidate the impact of XLS on classical inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10. Fourth, The safety endpoints were derived from only 6 studies, with a total sample size of 450, potentially constraining the comprehension of safety in the present study. Therefore, an accurate assessment of drug safety requires observation and analysis across a more substantial patient cohort. The authors recommend that future studies should focus on the evaluation of the safety of XLS and enrich the evaluation indicators of adverse events while conducting large-sample clinical trials.

The addition of XLS alleviated the clinical symptoms, intestinal mucosal injury, and inflammatory response in patients with UC, while demonstrating good safety.

| 1. | Ordás I, Eckmann L, Talamini M, Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2012;380:1606-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1151] [Cited by in RCA: 1543] [Article Influence: 118.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | da Silva BC, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Santana GO. Epidemiology, demographic characteristics and prognostic predictors of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9458-9467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Ulcerative colitis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:1553-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 4. | Christensen KR, Ainsworth MA, Skougaard M, Steenholdt C, Buhl S, Brynskov J, Kristensen LE, Jørgensen TS. Identifying and understanding disease burden in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang Y, Wang P, Shao L. Correlation of ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:2814-2822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee JW. Ulcerative Colitis and Patient's Quality of Life, Especially in Early Stage. Gut Liver. 2022;16:317-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berends SE, Strik AS, Löwenberg M, D'Haens GR, Mathôt RAA. Clinical Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations in the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:15-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ham M, Moss AC. Mesalamine in the treatment and maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012;5:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang L, Liu TG, Chen B, Liu SY, Ma XY, He JZ, He Y, Gu XH. [Textual research on Xilei Powder]. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi. 2020;45:4262-4266. |

| 10. | Dai JP. [Study on the Mechanism and Effective Fractions of Xilei San to Promote Mucosal Ulcers Healing]. Jiangsu University. 2012;. |

| 11. | Zhu Y, Xie H. Efficacy comparison of Xilei San and Mesalazine enemas for active distal ulcerative colitis. WCJD. 2008;16:3700. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu KC, Liang J, Ran ZH, Qian JM, Yang H, Chen MH, He Y. [Chinese consensus on diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (Beijing, 2018)]. Zhongguo Shiyong Neike Zazhi. 2018;38:796-813. |

| 13. | Cai Y, He MJ, Luo PP. [Effect of Mesalamine combined with Tin Powder enema in the treatment of ulcerative colitis andits influence on the immune function and cytokines of patients]. Zhongguo Xiandai Yixue. 2022;29:60-64. |

| 14. | Ding SY. [Clinical effects of retention enemas of Xilei San oxide combined with oral mesalazine in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Zhongguo Nongcun Weisheng. 2019;11:60. |

| 15. | Ge YL, Wu H. [Clinical efficacy of mesalazine combined with Xi Lei Powder enema in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Haixia Yaoxue Zazhi. 2011;23:114-115. |

| 16. | Li Y. [Efficacy of oral mesalazine combined with modified retention enemas of Xilei San in the treatment of ulcerative colitis in the elderly]. Jiankang Bidu. 2017;43:168-170. |

| 17. | Liu WJ. [Clinical observation on 56 cases of ulcerative colitis treated by mesalazine enteric-coated tablets combined with Xileisan]. Yixue Luntan Zazhi. 2015;36:150-151. |

| 18. | Ni GT, Chen SH. [Therapeutic efficacy of mesalazine combined with Xi Lei Powder in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Jiangxi Yixue Zazhi. 2011;46:923-924. |

| 19. | Wang SP. [Clinical efficacy of mesalazine oral combined with Xilei San enema in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Guizhou Yixue Zazhi. 2016;40:168-170. |

| 20. | Xu XQ, Wang XF. [Mesalazine combined with Xi Lei Powder enema in the treatment of ulcerative colitis in 84 cases]. Zhongguo Zhongyiyao Xinxi Zazhi. 2010;2:168-169. |

| 21. | Yao ZG, Yang WW. [Clinical efficacy of Xilei San enema combined with mesalazine in the treatment of damp-heat ulcerative colitis and its effect on the disease activity index]. Zhongguo Chufangyao Zazhi. 2022;20:138-140. |

| 22. | Zhang GY. [Thirty-five cases of ulcerative colitis treated with Xi Lei Powder combined with mesalazine enteric-coated tablets]. Zhongguo Zhiyao. 2013;22:99. |

| 23. | Zhang ZF, Nie XZ. [Efficacy and adverse effects of retention enemas with Xilei Powder and mesalazine enteric-coated tablets in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Dangdai Yixue. 2016;22:148-149. |

| 24. | Zhu HR. [The Clinical Efficacy for Enteric-coated Tablets Oral Mesalazine Joint Xileisan Retention Enema inthe Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis]. Zhongguo Yiyao Zhinan. 2013;11:58-59. |

| 25. | Zhu Y, Xie HZ. [Effect of Xi Lei Powder enemas and Mesalazine for active ulcerative colitis]. Xinjiang Yike Daxue Xuebao. 2009;32:1459-1461. |

| 26. | Cohen RD, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Xie J, Mulani PM, Chao J. Systematic review: the costs of ulcerative colitis in Western countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:693-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pilon D, Ding Z, Muser E, Obando C, Voelker J, Manceur AM, Kinkead F, Lafeuille MH, Lefebvre P. Long-term direct and indirect costs of ulcerative colitis in a privately-insured United States population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:1285-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | D'Amico F, Fasulo E, Jairath V, Paridaens K, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Management and treatment optimization of patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024;20:277-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rosiou K, Selinger CP. Acute severe ulcerative colitis: management advice for internal medicine and emergency physicians. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:1433-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Segal JP, LeBlanc JF, Hart AL. Ulcerative colitis: an update. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21:135-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wehkamp J, Stange EF. Recent advances and emerging therapies in the non-surgical management of ulcerative colitis. F1000Res. 2018;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Moss AC, Peppercorn MA. The risks and the benefits of mesalazine as a treatment for ulcerative colitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD000544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | West R, Russel M, Bodelier A, Kuijvenhoven J, Bruin K, Jansen J, Van der Meulen A, Keulen E, Wolters L, Ouwendijk R, Bezemer G, Koussoulas V, Tang T, Van Dobbenburgh A, Van Nistelrooy M, Minderhoud I, Vandebosch S, Lubbinge H. Lower Risk of Recurrence with a Higher Induction Dose of Mesalazine and Longer Duration of Treatment in Ulcerative Colitis: Results from the Dutch, Non-Interventional, IMPACT Study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2022;31:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Huang L, Wu Q, Cui RY, Tuo T, Xiao Y, Pan YS. [Progress in the study of the clinical expansion of the application of Xilei San]. Jichu Zhongyi Zazhi. 2016;22. |

| 36. | Xu F. [Curing Ulcerative Colitis with Chinese Herbal Binpeng Powder and Xilei Powder]. Jiangsu Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 1964;. |

| 37. | Sun XX. [Retention enema of a mixture of stannous and safranin in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Zhonguo Chuji Wiesheng Baojian. 1988;. |

| 38. | Wei R, Sun PL, Geng SG, Zhong YS. [Research progress of traditional Chinese medicine enema in the treatment of ulcerative colitis]. Hunan Zhongyiyao Zazhi. 2019;35:149-151. |

| 39. | Pabla BS, Schwartz DA. Assessing Severity of Disease in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020;49:671-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Song DX, He HQ, Zhang WL, Shao Q, Li YP. [Effects of chymotrypsin combined with xileisan on intestinal mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitisand study on its mechanism]. Zhongguo Zhongxiyi Jiehe Xiaohua Zazhi. 2019;27:179-185. |

| 41. | Jia WP, Zhang Y, Ni J, Li X. [Effect of ileisan temperature-sensitive gels on endothelial nitric oxide synthase, vascularendothelial growth factor A and tumor necrosis factor-a expression in rats with bleeding internahemorrhoids]. Yufang Yixue. 2023;35:27-31. |