Published online Jul 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4566

Revised: June 6, 2024

Accepted: June 20, 2024

Published online: July 26, 2024

Processing time: 68 Days and 3.3 Hours

The Cariostat caries activity test (CAT) was used to evaluate the effectiveness of personalized oral hygiene management combining oral health education and professional mechanical tooth cleaning on the oral health status of pregnant women.

To investigate whether personalized oral hygiene management enhances the oral health status of pregnant women.

A total of 114 pregnant women who were examined at Dalian Women’s and Children’s Medical Center were divided into four groups: High-risk experimental group (n = 29; CAT score ≥ 2; received personalized oral hygiene management training), low-risk experimental group (n = 29; CAT score ≤ 1; received oral health education), high-risk control group (n = 28; CAT score ≥ 2), and low-risk control group (n = 28; CAT score ≤ 1). No hygiene intervention was provided to control groups. CAT scores at different times were compared using independent samples t-test and least significant difference t-test.

No significant difference in baseline CAT scores was observed between the experimental and control groups, either in the high-risk or low-risk groups. CAT scores were reduced significantly after 3 (1.74 ± 0.47 vs 2.50 ± 0.38, P < 0.0001) and 6 months (0.53 ± 0.50 vs 2.45 ± 0.42, P < 0.0001) of personalized oral hygiene management intervention but not after oral health education alone (0.43 ± 0.39 vs 0.46 ± 0.33, P > 0.05 and 0.45 ± 0.36 vs 0.57 ± 0.32, P > 0.05, respectively). Within groups, the decrease in CAT scores was significant (2.43 ± 0.44 vs 1.74 ± 0.47 vs 0.53 ± 0.50, P < 0.0001) for only the high-risk experimental group.

Personalized oral hygiene management is effective in improving the oral health of pregnant women and can improve pregnancy outcomes and the oral health of the general population.

Core Tip: The Cariostat caries activity test (CAT) was used to evaluate the effectiveness of personalized oral hygiene management combining oral health education and professional mechanical tooth cleaning on the oral health of pregnant women. CAT scores were significantly improved after 3 months and 6 months of personalized oral hygiene management. However, oral health education alone did not improve the scores. Personalized oral hygiene management is effective in improving the oral health of pregnant women and can improve pregnancy outcomes and the oral health of the general population.

- Citation: Men XC, Du XP, Ji Y. Effects of personalized oral hygiene management on oral health status of pregnant women. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(21): 4566-4573

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i21/4566.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4566

In China, oral health is an important national concern. Since 1989, every year, National Dental Care Day is celebrated on September 20, focusing on a different theme for a series of promotional activities. In 2019, the National Health Commission also implemented the Healthy Dental Action Program (2019–2025)[1], which emphasized that oral health is an essential component of overall health. Pregnancy is an important part of women’s lives and has received special attention. However, oral diseases during pregnancy adversely affect the health of the mother and fetus. Many studies have revealed that oral disease during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, and low birth weight of infants[2,3]. Therefore, oral health during pregnancy is particularly important.

Caries and gingivitis are more likely to occur in pregnant women than in the general population because of increases in estrogen levels, changes in dietary habits, and early pregnancy reactions[4,5]. During pregnancy, caries is mainly caused by vomiting, which acidifies the oral environment. Moreover, demand for carbohydrates during pregnancy further increases the risk of caries because carbohydrates provide nutrients for the reproduction of bacteria, and the metabolism of the bacteria produces acid to demineralize the enamel, which can further worsen caries[5]. Untreated caries can result in local and systemic diseases[6]. Cariogenic Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes), which is present in the saliva of pregnant women with severe caries, is easily transmitted to the fetuses, which increases the risk of early neonatal caries[5]. Therefore, improving the oral hygiene of women during pregnancy to reduce the risk of caries is the focus of current research.

The Cariostat caries activity test (CAT) is a method for determining the risk of caries by assessing the acid-producing ability and quantity of cariogenic bacteria. The test results can be used to predict the occurrence and progression of caries[7]. Cariogenic bacteria such as S. pyogenes and Lactococcus lactis produce acid and are themselves resistant to acids; thus, the formation and promotion of cariogenic biofilms can lead to the occurrence and progression of caries[8]. Many tests for caries activity are currently available. In this study, to examine caries activity in the participants, the Cariostat test was used. The test was developed by Makoto Shimono in Japan in the 1970s and has been widely used in Japanese clinics because of the simplicity and safety of the test and the accuracy and reliability of the results[9].

Improving oral hygiene is an effective way to reduce caries. Professional mechanical tooth cleaning (PMTC) is a new technology, widely used in clinical practice in China and abroad, in which professional instruments are used to clean the tooth surface and gingiva, to help remove plaque on the tooth surfaces that cannot be reached usually and are easily neglected, and to apply fluoride varnish. Regular PMTC can significantly reduce the incidence of caries and systemic diseases caused by oral bacterial infection[10,11]. It can also effectively prevent gingivitis and periodontitis[12,13]. Personalized oral hygiene management is a combination of PMTC and a personalized program that includes education and nutritional counseling. However, the effect of personalized oral hygiene management on women’s oral health during pregnancy has not been reported. This study investigated the effect of personalization on oral health status, as determined using the CAT scores of pregnant women.

A total of 120 midpregnant women who underwent antenatal examinations at the Dalian Women’s and Children’s Medical Center, Dalian, China, from June to September 2022 were recruited for this study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Women aged 22–40 years during the 12th week of pregnancy; (2) Participants with independent comprehension and writing skills; and (3) Participants with no history of systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease) or of medication use (e.g., antiepileptic drugs, calcium channel blockers, or antibiotics). The Cariostat CAT was administered to 120 women who simultaneously completed a questionnaire (described in the next section).

Based on the CAT scores, the participants were divided into a high-risk group (CAT scores, ≥ 2; n = 60) or a low-risk group (CAT scores, ≤ 1; n = 60). The two groups were further subdivided into an experimental group (n = 30) and a control group (n = 30). Women for whom data were missing as a result of missed visits at a later stage were excluded from the study; the final number of participants was 114 (29 in the high-risk experimental group, 29 in the low-risk experimental group, 28 in the high-risk control group, and 28 in the low-risk control group). The high-risk experimental group received personalized oral hygiene management, including oral health education and PMTC, and the low-risk experimental group received oral health education alone. The high-risk and low-risk control groups received no intervention.

Demographic information (e.g., age, education level), personal medical history (pregnancy history, week of pregnancy, etc.), occupation, and information about oral examinations and treatment were collected from each participant.

At the beginning of the study, all participants completed a questionnaire consisting of two parts. The first part concerned demographic and obstetric information, including age, education level, number of births, and week of pregnancy. The second part, which concerned oral health, consisted of 17 questions, of which one concerned the number of times the participants brushed their teeth directly, and the others required “yes” or “no” responses: Five concerned dental caries; three concerning gum disease; four concerning participants’ awareness of the importance of oral health and daily habits; three concerning the relationship between oral health and adverse pregnancy outcomes; and two concerning participants’ willingness to learn about and receive oral health care (Table 1).

| Question | Response | |

| Yes | No | |

| 1. Can eating sweets lead to tooth decay? | 109 (90.83) | 19 (9.17) |

| 2. Can tooth decay affect people’s work or other aspects of their daily lives? | 103 (85.83) | 17 (14.16) |

| 3. Do cavities make you look bad? | 86 (71.67) | 34 (28.33) |

| 4. Should every painful tooth be extracted? | 98 (81.67) | 22 (18.33) |

| 5. Do you know what gum disease is? | 73 (60.84) | 47 (39.16) |

| 6. Did you know that bleeding while brushing your teeth hints at gum problems? | 69 (57.50) | 51 (42.50) |

| 7. Does pregnancy increase the tendency of gums to bleed, swell, or turn red? | 55 (45.83) | 65 (54.17) |

| 8. Does brushing with fluoridated toothpaste help prevent tooth decay? | 91 (75.83) | 29 (24.17) |

| 9. Do you change your toothbrush often? | 83 (69.17) | 37 (30.83) |

| 10. Did you know that there are other oral hygiene regimens? | 89 (74.17) | 31 (25.83) |

| 11. Is oral health important for general physical health? | 103 (85.83) | 17 (14.16) |

| 12. Did you know that there is a link between oral health (teeth and gum problems) and pregnancy? | 41 (34.17) | 79 (65.83) |

| 13. Can poor oral health affect an unborn baby? | 39 (32.50) | 81 (67.50) |

| 14. Do you go to the dentist often? | 32 (26.67) | 88 (73.33) |

| 15. Do you want to know how to keep your teeth clean? | 119 (99.17) | 1 (0.83) |

| 16. Are you ready for a dental check-up or treatment if necessary? | 120 (100.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| 17. What is the average number of times per day you brush your teeth? | 1.98 ± 0.48 | |

Personalized oral hygiene management combining oral health education and PMTC was provided to the high-risk experimental group. Oral health education covered topics such as the causes and hazards of dental caries and gingival diseases, oral diseases that occur during pregnancy, daily oral care, and oral hygiene practices that should be followed during pregnancy. To increase participants’ acceptance of the instructions, lectures were delivered in various forms. Online and offline courses were provided, along with teaching molds and the sharing of classic cases. In addition, to further improve the education, the high-risk experimental group was offered individual counseling on the problems identified in the questionnaire, and online oral questions and answers were available at any time.

In PMTC, plaque stain was applied to the teeth surfaces and interdental areas; the mouth was rinsed; the staining was observed; stained areas were subjected to grinding, sweeping, and rinsing after abrasive was applied; and fluoride was applied to the tooth surfaces and cusps. This protocol was performed weekly.

A dentist and a trained dental hygienist performed the oral examinations. The oral cavity of each participant was examined using an orofacial microscope and a probe.

To perform CAT, plaque samples were collected by swabbing the buccal side of the maxillary molars and the labial side of the mandibular anterior teeth three times and then immersing the swabs in caries-enhancing medium and incubating them for 48 hours at 37 °C. The CAT scores were then determined according to the change in colors of the medium: Blue was scored as 0, green as 1, greenish yellow as 2, and yellow as 3. When a color was intermediate between the shades, the mean was recorded. This method was repeated for 118 participants 3 and 6 months after the start of treatment in the experimental groups.

The data were calculated as frequencies, means, and standard deviations. For intergroup comparisons, the independent samples t-test was performed to compare the CAT scores of the experimental and control groups before, 3 months after, and 6 months after treatment began for the experimental groups. For within-group comparisons, the least significant difference t-test was performed to identify differences in the CAT scores within the experimental and control groups before, 3 months after, and 6 months after treatment began for the experimental groups. All data were processed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 (released 2015; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States).

Table 1 lists the responses of 120 participants to the questionnaire. Overall, the responses related to dental caries were correct; most participants (90.83%) were aware that consuming sweets could lead to cavities, and 85.83% acknowledged that cavities would adversely affect their daily life significantly. Most participants agreed that tooth decay affected esthetics and that toothache should be promptly treated. Most knew that fluoride toothpaste is effective in preventing tooth decay, but far fewer knew about gum disease, even fewer knew that bleeding while brushing is related to gum disease, and only 45.83% knew that pregnancy increases the likelihood of gum disease. In relation to oral health care, nearly all the participants demonstrated a high level of interest, and the majority had good knowledge about it and knew that oral health was important to general physical health. The majority of participants regularly replaced their toothbrushes, but many visited the dentist only when they suffered from oral diseases. Two-thirds of the pregnant women were aware of the effects of oral health on pregnancy, but only 32.50% were aware of its effects on pregnancy outcomes. The frequency of brushing was also recorded. Few participants brushed three times a day, few brushed only once, but most brushed twice.

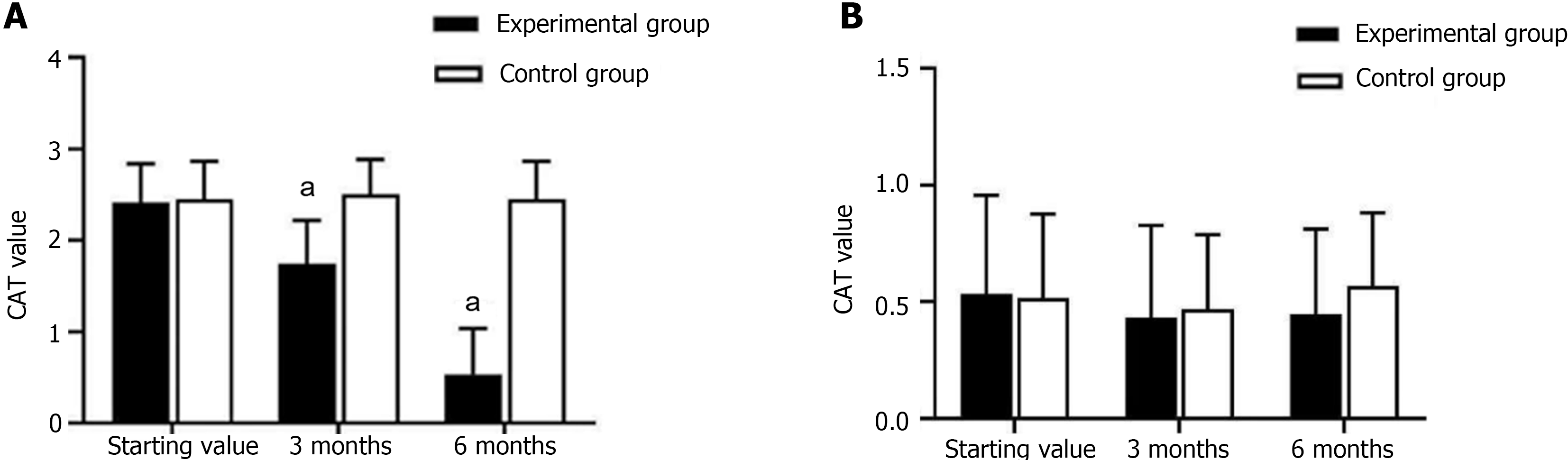

Table 2 shows the CAT scores of the experimental and control groups. Darker color shades represent higher mean CAT scores; green indicates a significant difference between scores (P < 0.05), and red indicates no significant difference (P > 0.05). Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the baseline CAT scores of the experimental and control groups within the high- and low-risk cohorts (P > 0.05). However, the CAT scores of the high-risk experimental group were significantly lower than those of the high-risk control group (P < 0.0001) at both 3 months (mean difference, 0.76) and 6 months (mean difference, 1.92) after treatment began for the experimental group (Figure 1A). Within the low-risk cohort, CAT scores did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) between the experimental and control groups 3 and 6 months after treatment began for the experimental group (Figure 1B).

| Time of CAT | High-risk groups | Low-risk groups | ||

| Experimental group (n = 29) | Control group (n = 28) | Experimental group (n = 29) | Control group (n = 28) | |

| Initial | 2.43 ± 0.44 | 2.45 ± 0.42 | 0.53 ± 0.42 | 0.50 ± 0.36 |

| After 3 months | 1.74 ± 0.47a | 2.50 ± 0.38 | 0.43 ± 0.39 | 0.46 ± 0.33 |

| After 6 months | 0.53 ± 0.50a | 2.45 ± 0.42 | 0.45 ± 0.36 | 0.57 ± 0.32 |

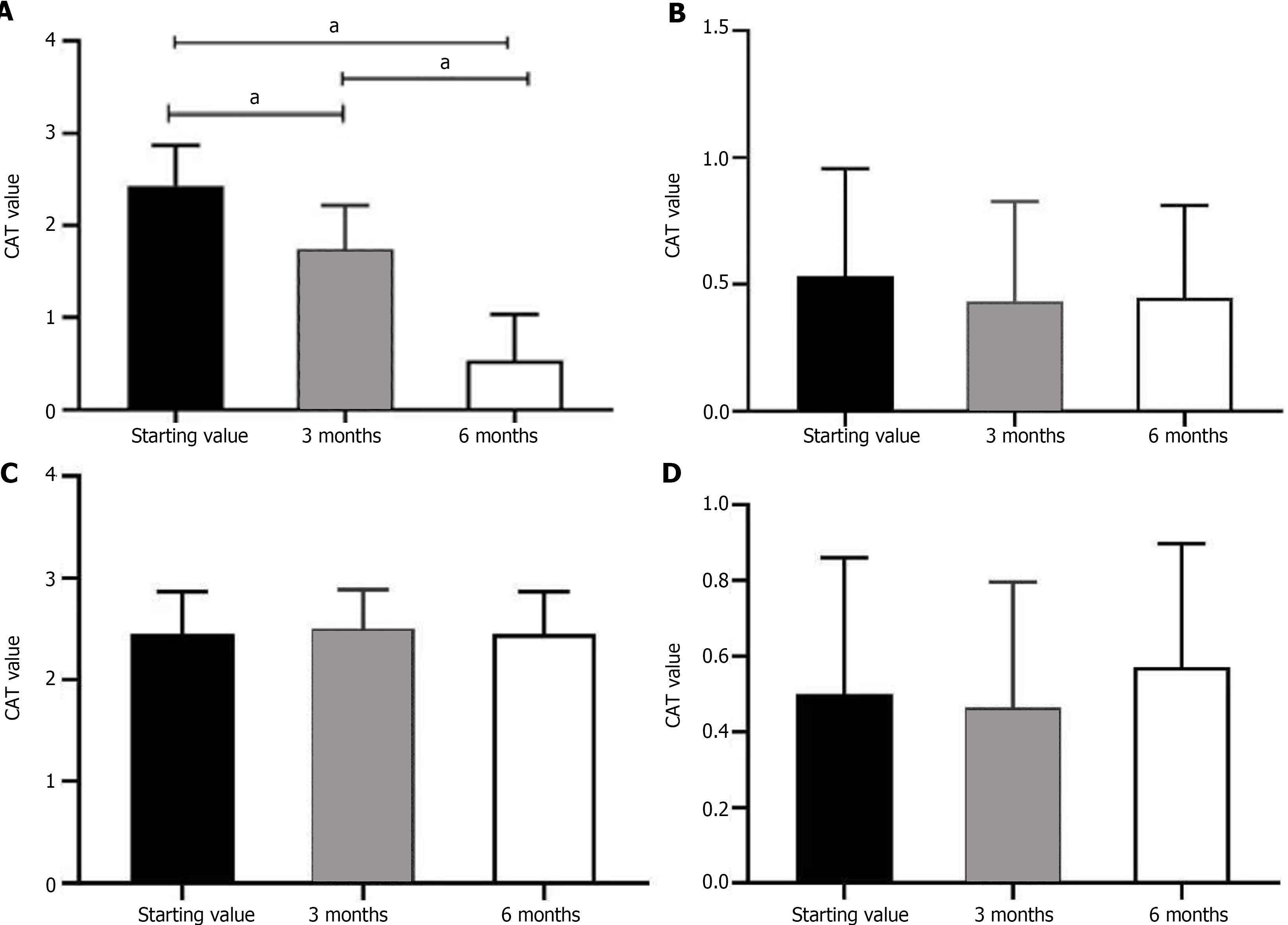

Table 3 displays the results of intragroup comparisons. Darker shades of color represent higher mean CAT scores, green indicates a significant difference between scores (P < 0.05), and red indicates no significant difference (P > 0.05). In the high-risk experimental group, CAT scores decreased significantly after 3 months of personalized oral hygiene management (P < 0.05; mean difference, 0.69) and after 6 months. The 6-month CAT scores were significantly different from the initial scores (P < 0.05) and were significantly lower than the 3-month CAT scores (P < 0.05; mean difference = 1.21; Figure 2A). Unlike the CAT scores of the high-risk experimental group, those of the low-risk experimental group did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) after participants received only oral health education (Figure 2B). Initial CAT scores of both control groups did not differ significantly (P > 0.05; Figure 2C and D).

| Time of CAT | Experimental groups | Control groups | |||

| High-risk group (n = 29) | Low-risk group (n = 29) | High-risk group (n = 28) | Low-risk group (n = 28) | ||

| Initial | 2.43 ± 0.44 | 0.53 ± 0.42 | 2.45 ± 0.42 | 0.50 ± 0.36 | |

| After 3 months | 1.74 ± 0.47a | 0.43 ± 0.39 | 2.50 ± 0.38 | 0.46 ± 0.33 | |

| After 6 months | 0.53 ± 0.50a | 0.45 ± 0.36 | 2.45 ± 0.42 | 0.57 ± 0.32 | |

In 2019, the National Health Commission of China implemented the Healthy Mouth Action Program (2019–2025) to increase oral health awareness and promote oral health–enhancing behavior in the public. Preventing and treating dental caries have long been a subject of social research, and many studies have focused on children[14]. In 2021, the National Health Commission implemented the Action Plan for Improvement of Maternal and Infant Safety (2021–2025)[15], which emphasizes hygiene and maternal and infant safety. As the importance of pregnancy-related health has been increasingly recognized, oral health during pregnancy has also become a concern. Oral health during pregnancy can have a significant effect both on the daily eating habits and digestion of pregnant women and on the outcome of pregnancy.

Several studies have revealed a correlation between oral diseases and adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm labor and pre-eclampsia. Despite these findings, most participants in this study were unaware of the negative effects of poor oral health on pregnancy, as indicated by their responses to the questionnaire. The questionnaire results indicate that most participants responded knowledgeably to questions regarding dental caries, including prevention and willingness to seek treatment. However, some participants showed less understanding of gingival problems. Moreover, daily oral hygiene habits were inconsistent; some participants had better habits than others. Because the study population was small as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and limited to local residents of Dalian, the results may not fully represent the awareness level of pregnant women nationwide; however, the questionnaire results might nonetheless reflect the overall awareness levels of pregnant women in Dalian. This information can guide the further development of personalized oral health education during pregnancy in Dalian.

Because of physiological changes that occur during pregnancy, pregnant women are more susceptible to oral diseases, such as dental caries, than the general population. PMTC technology has a proven preventive effect against dental caries, gingivitis, periodontitis, and other oral diseases[11]. The claim that PMTC prevents caries and provides oral hygiene benefits for pregnant women is not supported by evidence, and studies on the effects of personalized oral hygiene management (the combination of PMTC with oral health education) on oral health during pregnancy have not been reported previously. Therefore, this study focused on the associations between personalized oral hygiene management and oral health in pregnant women.

The results of the intergroup comparison indicate that the CAT scores of the participants remained unchanged after oral health education, as did the risk of caries. However, personalized oral hygiene management has the potential to significantly improve both the scores and the risk in pregnant women. Three months after treatment began, the CAT scores of participants who received personalized oral hygiene management significantly improved, indicating that personalized oral hygiene management has a quick onset of action and is effective. The study findings will help guide the further application of personalized oral hygiene management to pregnant women in the Dalian Women’s and Children’s Medical Center. This management is a novel, convenient, and safe way to prevent and treat oral diseases, particularly caries, during pregnancy. This approach also reflects the hygiene policy.

Intragroup comparisons revealed that the average CAT score in the high-risk experimental group decreased significantly from the beginning to the end of the 6-month period, and the decrease was more pronounced in the second 3 months than in the first 3 months. This decrease, achieved through weekly personalized oral hygiene management, indicates that personalized oral hygiene management can significantly benefit patients with high CAT scores and poor oral health status. Moreover, the average CAT score of the high-risk experimental group decreased to < 2 after 3 months of treatment and continued to decrease with further application. By the third month, the average CAT scores of the participants had already reached the low-risk level, which is an indicator of good oral health status. Therefore, PMTC is suitable for patients with poor oral health and improves oral hygiene in patients with good oral health.

Improvements in oral health during pregnancy can reduce the risk of transmission of oral pathogens from pregnant women to their newborns after delivery. This outcome may positively affect the oral hygiene habits of the next generation, which will further help reduce the risk of caries in infants and young children and may contribute to improving the oral health of the entire nation.

The control groups were established to enhance the reliability of the results for the experimental groups. Because the CAT scores of the control groups did not change significantly, they could not have been affected by changes in the participants’ oral hygiene habits for their own reasons or by external disturbances. Therefore, the changes in the experimental groups and the differences between the experimental and control groups probably resulted from personalized oral hygiene management. The findings also indicate that oral health education alone is insufficient for improving the oral health status of pregnant women; thus, education must be accompanied by professional treatment.

The limitations of this study are the small sample size and lack of data because of missed late visits. Therefore, future studies should have larger sample sizes.

The results of the questionnaire and intra- and intergroup comparisons indicate that pregnant women need to be educated about the importance of oral health. Personalized oral hygiene management could effectively improve women’s oral health during pregnancy, potentially leading to better pregnancy outcomes and overall improvement in the oral health of the general population.

| 1. | Cai H, Cheng YT, Ren XL, Cheng L, Hu T, Zhou XD. Recent Developments and Future Directions of Oral Healthcare System and Dental Public Health System in China in Light of the Current Global Emergency. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;53:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sinha A, Singh N, Gupta A, Bhargava T, P C M, Kumar P. Relationship Between the Periodontal Status of Pregnant Women and the Incidence and Severity of Pre-term and/or Low Birth Weight Deliveries: A Retrospective Observational Case-Control Study. Cureus. 2022;14:e31735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daalderop LA, Wieland BV, Tomsin K, Reyes L, Kramer BW, Vanterpool SF, Been JV. Periodontal Disease and Pregnancy Outcomes: Overview of Systematic Reviews. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2018;3:10-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu M, Chen SW, Jiang SY. Relationship between gingival inflammation and pregnancy. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:623427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kloetzel MK, Huebner CE, Milgrom P. Referrals for dental care during pregnancy. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Achtari MD, Georgakopoulou EA, Afentoulide N. Dental care throughout pregnancy: what a dentist must know. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2012;11:169-176. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Xie P, Wang XQ, Bao XT, Wang M. [Experimental study on caries activity in deciduous teeth]. Zhonguo Fuyou Baojian Zazhi. 2004;19:117-118. |

| 8. | Li YJ, Wang W, Pan YT, Chen LY, Fan XM, Tian Y. [Study on the distribution and function of cariogenic bacteria in supragingival plaque in patients with type 2 diabetes]. Kouqiang Jibing Fangzhi. 2023;31:321-327. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Xuan SY, Yuan JW, Wang J, Guan XL, Ge LH, Shimono YM. [A 2-year cohort study on the caries risk assessment of 3-year-old caries-free children using Cariostat caries activity test]. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2017;52:667-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nomura Y, Takeuchi H, Kaneko N, Matin K, Iguchi R, Toyoshima Y, Kono Y, Ikemi T, Imai S, Nishizawa T, Fukushima K, Hanada N. Feasibility of eradication of mutans streptococci from oral cavities. J Oral Sci. 2004;46:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao RN. [Professional tooth cleaning (PMTC) technology]. Zhongguo Meirong Yixue. 2008;17:1653-1655. |

| 12. | Li J, Chen B, Liu P, Shi AT, Zhou SJ, Xiang XR. [The prevention and treatment effect of specialized tooth cleaning technology on adolescent gingivitis]. Xiandai Yixue Yu Jiankang. 2018;34:3. |

| 13. | Ono T, Nakashima T. Oral bone biology. J Oral Biosci. 2022;64:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lin X, Wang Y, Ma Z, Xie M, Liu Z, Cheng J, Tian Y, Shi H. Correlation between caries activity and salivary microbiota in preschool children. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1141474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu ZC, Song B, Gao Q, Wang Q, Wang XY, Huang DX, Wang AL. [Improving the quality of maternal and child safety services and maintaining the health of women and children: Interpretation of the Maternal and Child Safety Action Plan (2021-2025)]. Zhongguo Fuyou Baojian Zazhi. 2022;13:1-4. |