Published online Jul 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4518

Revised: May 8, 2024

Accepted: May 27, 2024

Published online: July 26, 2024

Processing time: 118 Days and 9.8 Hours

Febrile convulsions are a common pediatric emergency that imposes significant psychological stress on children and their families. Targeted emergency care and psychological nursing are widely applied in clinical practice, but their value and impact on the management of pediatric febrile convulsions are unclear.

To determine the impact of targeted emergency nursing combined with psychological nursing on satisfaction in children with febrile convulsions.

Data from 111 children with febrile convulsions who received treatment at Nantong Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital between June 2021 and October 2022 were analyzed. The control group consisted of 44 children who received conventional nursing care and the research group consisted of 67 children who received targeted emergency and psychological nursing. The time to fever resolution, time to resolution of convulsions, length of hospital stays, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, patient compliance, nursing satisfaction of the parents, occurrence of complications during the nursing process, and parental anxiety and depression were compared between the control and research groups. Parental anxiety and depression were assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA).

The fever resolution, convulsion disappearance, and hospitalization times were longer in the control group compared with the research group (P < 0.0001). The time to falling asleep, sleep time, sleep quality, sleep disturbance, sleep efficiency, and daytime status scores were significantly better in the research group com

Combining psychological nursing with targeted emergency nursing improved the satisfaction of children’s families and compliance with treatment and promoted early recovery of clinical symptoms and improvement of sleep quality.

Core Tip: Targeted emergency nursing combined with psychological nursing in children with febrile convulsions exhibited significant benefits, including shorter duration of fever and convulsions, reduced hospitalization time, improved sleep quality, increased treatment compliance, higher parental satisfaction, lower occurrence of complications, and decreased parental anxiety and depression. This study highlights the importance of implementing comprehensive nursing strategies that address both the physical and psychological needs of children with febrile convulsions. Healthcare professionals can enhance outcomes and promote a positive experience for both children and their families by providing individualized care and employing techniques such as distraction, storytelling, and tailored interventions.

- Citation: Han Q, Wu FR, Hong Y, Gu LL, Zhu Y. Value of combining targeted emergency nursing with psychological nursing in children with febrile convulsions. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(21): 4518-4526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i21/4518.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i21.4518

Convulsions are a common pediatric emergency, and febrile convulsions are the most common pediatric convulsive disorder, with a prevalence of 3%–6.5%[1]. The onset of febrile convulsions is age dependent, with a high incidence between 6 months and 5 years of age. Febrile convulsions usually occur within 24 h after the onset of fever and present as generalized tonic–clonic seizures, mostly during the period of sudden temperature increase[2]. The National Institutes of Health defines febrile convulsions as “children usually 3 months to 5 years of age, often with fever, but without a clear cause of intracranial infection or seizures”[3,4]. In the updated International League Against Epilepsy classification and terminology, febrile convulsions are classified as “a condition of seizures not traditionally diagnosed as epilepsy per se”[5]. The convulsive threshold of febrile convulsions varies widely among individuals, with no obvious frequency and duration patterns; preventive and therapeutic drug use is controversial due to the unpredictability of febrile convulsions[6]. In a small number of children, complex febrile convulsions may progress to epilepsy later in life or cause cognitive and executive dysfunctions[7]. Hence, implementing effective interventions and preventive measures is crucial for reducing the incidence of complications related to febrile convulsions.

The sudden development of febrile convulsions in children may cause secondary injuries, such as artificial fractures and tooth loss due to inappropriate or overly aggressive treatment. In addition, families may become anxious and worried when children have convulsions and may have doubts about the recurrence and prognosis of febrile convulsions[8,9]. If pediatric febrile convulsions are not effectively and promptly treated, cerebral hypoxia, brain damage, and neurological dysfunction, which affect the healthy development and growth of children and endanger their lives, may develop[10]. Therefore, children with febrile convulsions should be treated as early as possible with efficient and safe emergency treatment based on scientific and rational nursing interventions.

Targeted emergency nursing is a new interventional model that emphasizes targeted care according to the patient’s actual situation. Pediatric fever and febrile convulsions can be controlled in a short period with targeted nursing, resulting in good prognosis[11]. In addition, psychological nursing interventions can enhance nurse–patient com

A retrospective analysis of data from 111 children with febrile convulsions who received treatment at Nantong Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital between June 2021 and October 2022 was conducted. Children who received conventional nursing care were assigned to the control group (n = 44), and children who received targeted emergency nursing and psychological nursing were assigned to the research group (n = 67).

The inclusion criteria were as follows: fever with convulsions meeting the diagnostic criteria for febrile convulsions in the 2016 Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Febrile Convulsions[13]; no history of febrile convulsions, except for central nervous system infections and other causes of convulsions; a previous clear diagnosis of febrile convulsions and no current fever-free convulsions; and complete clinical profile. Patients were excluded from the study for the following reasons: central nervous system infection, intracranial occupancy, cerebral hemorrhage, autoimmune encephalitis, trauma, electrolyte disorders, infantile gastroenteritis with benign convulsions, genetic metabolic diseases, congenital heart disease or other congenital disorders, systemic biochemical or metabolic disorders, intracranial infection, organic disease, metabolic abnormalities, or other causes of convulsions.

The control group received routine emergency care until the child was discharged from hospital. The nursing staff observed the child’s symptoms, signs, and facial demeanor to assist the physician in identifying the type and severity of the convulsions. Nursing staff untied the child’s collar, cleaned the respiratory secretions, and tilted the head to the side to avoid asphyxiation caused by vomiting. In addition, the nurses followed the doctor’s prescriptions for reasonable medications and monitored the child after medication. If serious convulsions occurred, gauze was placed in the child’s mouth to prevent biting the tongue. The nursing staff monitored the child’s temperature changes and implemented timely cooling interventions. Nurses changed the child’s clothing when sweating increased and maintained oral hygiene by keeping the mouth clean and moist. Basic dietary instructions were provided to promote appropriate hydration and sufficient energy intake.

The research group used targeted emergency nursing and psychological nursing until the children were discharged. Targeted first aid treatment included the following: Rescue on the spot to prevent injury; immediate opening of the airway for artificial respiration rescue measures, suction, and endotracheal intubation if the child exhibited symptoms of asphyxia; venous passage established as soon as possible, thicker venous vessels were selected during puncture; intravenous injection of an anticonvulsant and 20% mannitol upon the doctor’s advice if the child exhibited persistent convulsions, while controlling injection speed; and use of antipyretic drugs to cool the child, dextroibuprofen was placed in his anus and absorbed through the rectum to reduce fevers.

The targeted health education included the following: Nurses carried out systematic health education for parents so they could understand and recognize infantile febrile convulsions, including etiology, treatment, emergency measures to stop convulsion, and nursing measures to prevent injuries to children. The education enabled parents to actively cooperate with medical staff during clinical treatment and rescue in the event of convulsions during the absence of medical staff.

Targeted condition monitoring included closely monitoring the children. The occurrence time, duration, interval time, attack degree, and concomitant symptoms of convulsions were recorded. Changes in vital signs and muscle tone were monitored so convulsions caused by high fever could be detected and treated immediately to minimize brain damage.

For targeted psychological nursing, the nursing staff used various techniques based on the age and interests of the children, including showing cartoons, playing games, and telling stories to soothe them. These activities helped divert or distract the children’s attention and reduced fear and resistance during nursing procedures. At the same time, the nurses let the parents participate in medical rounds, answered parents' questions, addressed confusion, and ensured that the parents knew the condition of the children in real time. These actions built trust in the medical staff and relieved the psychological pressure of the parents.

During targeted discharge guidance, nurses comprehensively evaluated recovery of the children and emphasized to parents that children with febrile convulsions are prone to recurrent seizures. Parents were instructed to ensure that the children exercised appropriately to enhance their physical quality, immunity, and resistance, and prevent the recurrence of febrile convulsions during the recuperation time. The parents were instructed to administer oral antipyretics and sedatives to prevent a sudden rise in body temperature if the children developed a cold or were in the early stage of fever (within a few hours or 24 h). The use of warm water, ice water, or ethanol baths was not recommended to reduce fever, as these baths may increase the discomfort of children. Instead, parents were advised to administer antipyretic drugs at a minimum interval of 4 h and seek timely medical attention for observation and treatment at a hospital.

Primary outcome measures included time to fever reduction, time to resolution of convulsions, and time to hospitalization. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[14] was applied to determine sleep quality score, sleep onset score, sleep duration score, sleep efficiency score, sleep disorder score, daytime dysfunction score, and total PSQI score. The PSQI table contains six evaluation indicators with scores between 0 and 3, with higher scores representing poorer quality. Compliance was also evaluated. Compliance refers to the children’s complete cooperation with the instructions provided by the nursing staff. Basic compliance implies that the children can follow some instructions after receiving detailed explanations from the nursing staff. Noncompliance indicates that the children exhibit strong resistance and are less cooperative during nursing. Secondary outcome measures included clinical data and parental satisfaction with nursing. The occurrence of complications during the nursing of children was evaluated. Finally, parental anxiety and depression were assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAMA). Each scale had a maximum score of 20; higher scores represent more severe symptoms[15].

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 software and plotted using GraphPad8 software. Numerical data are expressed as a rate of use (%) and compared using χ2 tests. Continuous data are expressed as means ± SD and compared using independent sample t-tests, and within-group comparisons were achieved using paired t-tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

No significant differences in clinical data were detected between the control and research groups (P > 0.05, Table 1).

| Factor | Control group (n = 67) | Research group (n = 44) | χ2 value | P value | |

| Age | 0.351 | 0.553 | |||

| ≥ 2 years | 42 | 30 | |||

| < 2 years | 25 | 14 | |||

| Gender | 1.015 | 0.313 | |||

| Male | 37 | 20 | |||

| Female | 30 | 24 | |||

| BMI | 1.711 | 0.190 | |||

| ≥ 18 kg/m2 | 23 | 10 | |||

| < 18 kg/m2 | 44 | 34 | |||

| Duration of convulsions | 1.947 | 0.162 | |||

| ≥ 5 minutes | 29 | 25 | |||

| < 5 minutes | 38 | 19 | |||

| Type of convulsions | 0.780 | 0.377 | |||

| Simple type | 45 | 33 | |||

| Complex type | 22 | 11 | |||

| Causes of disease | 0.578 | 0.748 | |||

| Upper respiratory tract infections | 37 | 23 | |||

| Pneumonia | 20 | 12 | |||

| Bacterial dysentery | 10 | 9 | |||

| Family history of convulsions | 2.577 | 0.108 | |||

| Yes | 15 | 16 | |||

| No | 52 | 28 |

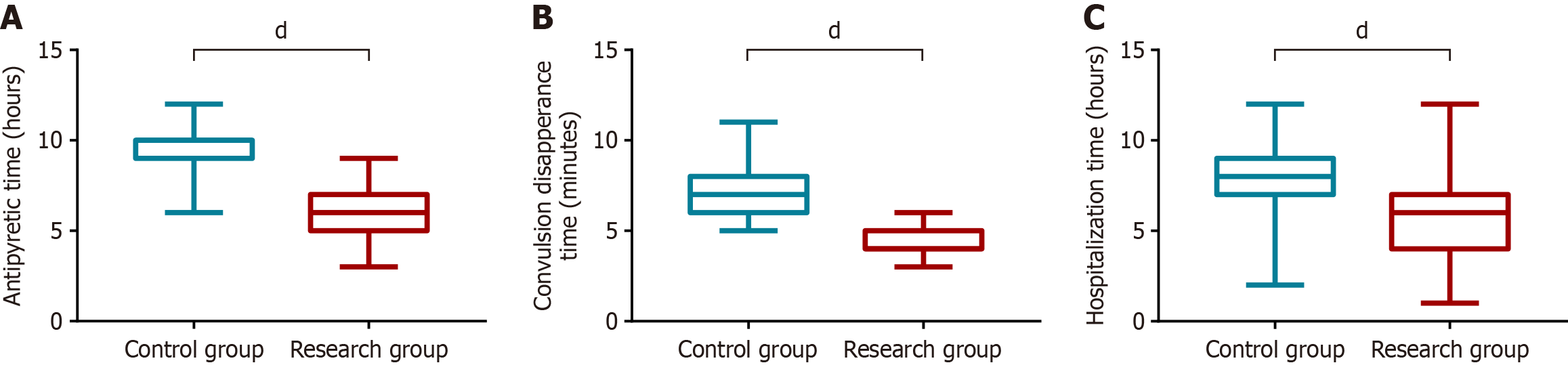

The times to resolution of fever, convulsions, and hospitalization were longer in the control group compared with the research group (P < 0.0001, Figure 1).

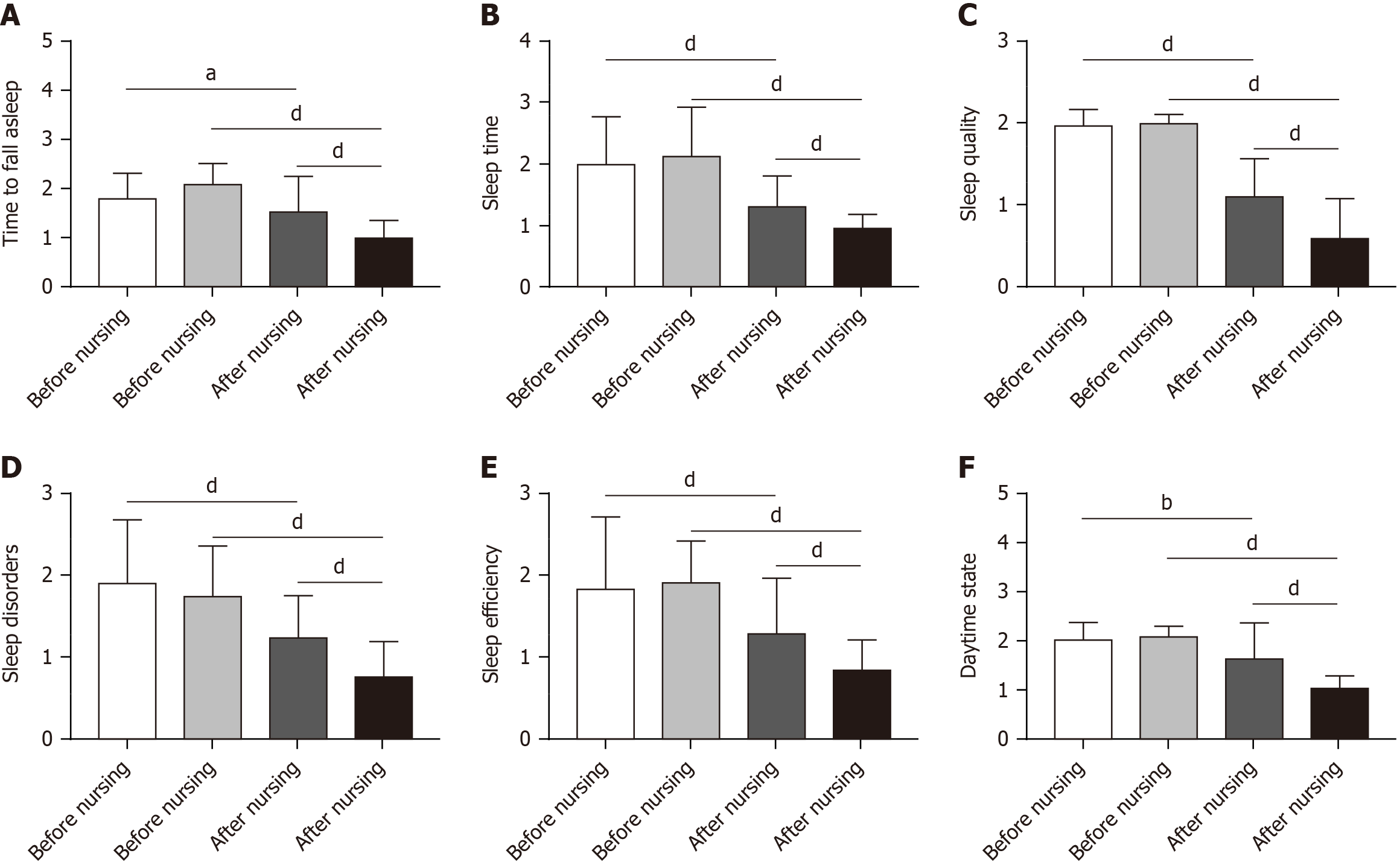

Before nursing interventions, no significant differences in sleep measures, including sleep duration, sleep time, sleep quality, sleep disturbance, sleep efficiency, and daytime functioning, were detected between the control and research groups (P > 0.05). The length of sleep, sleep time, sleep quality, sleep disturbance, sleep efficiency, and daytime status were significantly lower in both groups after nursing care compared with the precare period (P < 0.05). The length of sleep, sleep time, sleep quality, sleep disturbance, sleep efficiency, and daytime status scores of children were significantly better in the research group compared with the corresponding sleep parameters in the control group (P < 0.0001, Figure 2).

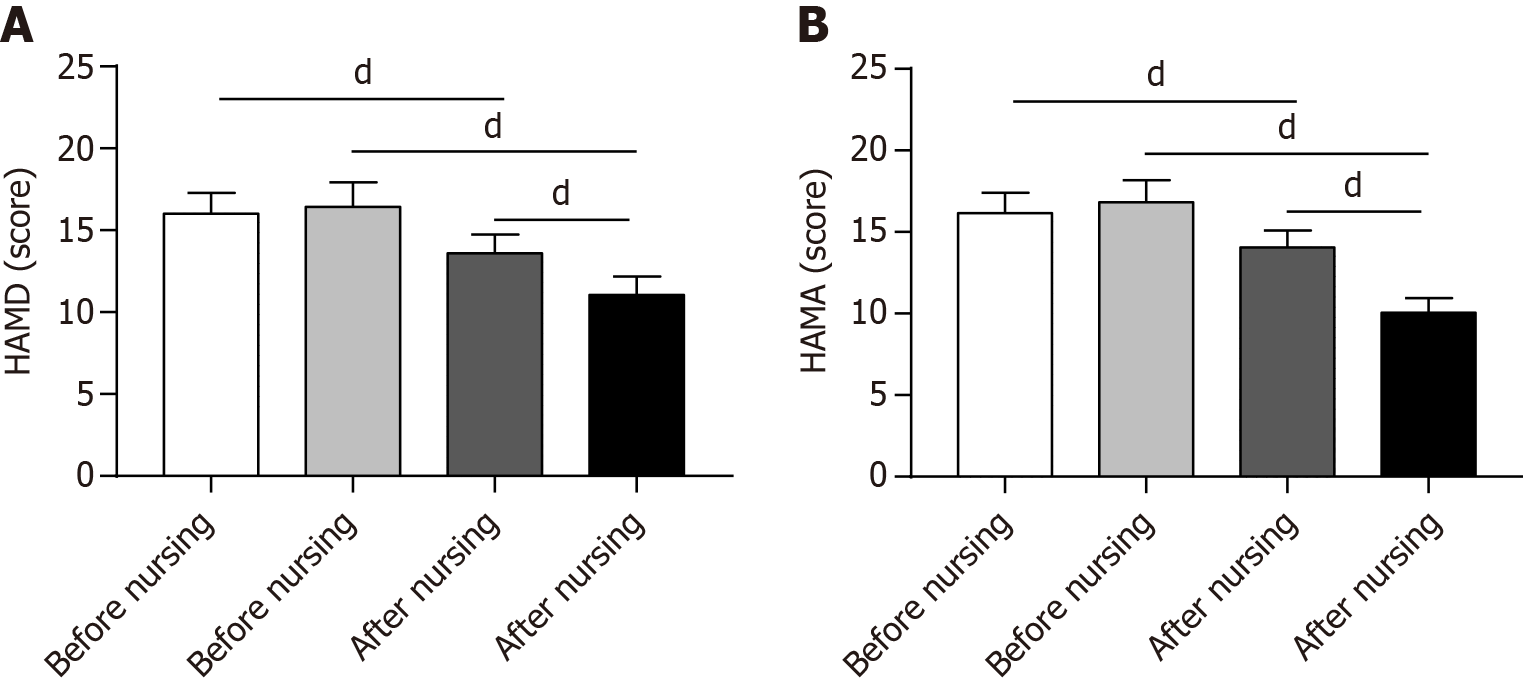

Before nursing care, no significant differences in parental HAMD and HAMA scores were detected between the two groups (P > 0.05). Parental HAMD and HAMA scores were significantly lower in both groups of children after nursing compared with before nursing (P < 0.05). After nursing care, the HAMD and HAMA scores of the parents of children in the research group were significantly lower than the scores of the parents of children in the control group (P < 0.05, Figure 3).

Compliance of the children in the research group was significantly higher than in the control group (P < 0.05, Table 2).

| Groups | Full compliance | Partial compliance | Noncompliance | Compliance rate |

| Control group (n = 67) | 33 (49.25) | 30 (44.77) | 4 (5.98) | 63 (94.02) |

| Research group (n = 44) | 18 (38.64) | 15 (34.09) | 11 (27.27) | 32 (72.73) |

| χ2 value | 8.268 | 8.553 | ||

| P value | 0.016 | 0.003 | ||

Children in the research group were significantly more satisfied with their nursing than children in the control group (P < 0.05, Table 3).

| Groups | Very satisfied | Basically satisfied | Dissatisfied | Satisfaction |

| Control group (n = 67) | 38 (56.73) | 24 (35.82) | 5 (7.45) | 62 (92.55) |

| Research group (n = 44) | 16 (36.37) | 18 (40.93) | 10 (22.70) | 34 (77.30) |

| χ2 value | 7.023 | 5.295 | ||

| P value | 0.029 | 0.021 | ||

The total complication rate of children in the control group was significantly higher than in the research group during nursing (P < 0.05, Table 4).

| Groups | Cerebral edema | Infection | Water–electrolyte disorders | Brain injury | Total incidence |

| Control group (n = 67) | 1 (1.49) | 2 (2.98) | 1 (1.49) | 1 (1.49) | 5 (7.45) |

| Research group (n = 44) | 3 (6.81) | 3 (6.81) | 2 (4.54) | 2 (4.54) | 10 (22.70) |

| χ2 value | 2.168 | 0.907 | 0.941 | 0.941 | 5.295 |

| P value | 0.140 | 0.340 | 0.331 | 0.331 | 0.021 |

Febrile convulsions, particularly among preschool children, pose a diagnostic challenge. Febrile convulsions usually occur without any clear warning signs and can be difficult to differentiate from central nervous system infections or febrile seizures associated with epilepsy[16]. Misdiagnosis can lead to treatment delays and cause panic within families. Without timely and effective intervention for febrile convulsions, brain damage and growth retardation can occur, significantly impacting the physical and mental health of children[17]. Moreover, febrile convulsions reoccur in > 30% of children[18]. Thus, providing timely and effective nursing care for children with febrile convulsions is crucial.

Targeted emergency nursing is a nursing model guided by the concept of modern nursing. Comprehensive pediatric nursing intervention facilitates optimal recovery, improves prognosis, reduces the risks of febrile convulsions, and promotes early recovery[19,20]. In one pediatric study[21], the parents of children who developed sudden onset of febrile convulsions experienced significant psychological distress. Limited understanding of the condition contributed to the negative psychological state of parents, causing anxiety, helplessness, and fear. Uncertainty about illness is a lack of ability to determine things related to the illness. Studies have shown that parents with high uncertainty about illness have a higher psychological burden, which affects their physical and mental health, and interferes with the care of their children, which may affect the children’s recovery[22]. Psychological nursing can increase nurse–patient communication and implement positive psychological guidance for the children and their families.

In the present study, we demonstrated that the time to fever resolution, time to disappearance of convulsions, and hospitalization time were shorter in the research group compared to the children in the conventional nursing group. In addition, sleep quality and compliance improved and complications decreased in children in the research group compared with the control group[23]. Jia et al[24] demonstrated that the time to recovery of temperature, time to convulsion control, and length of hospital stay in children with febrile convulsions were reduced by holistic nursing compared with conventional nursing, which is consistent with our findings. At present, there are no targeted clinical treatments for pediatric febrile convulsions. Targeted emergency treatment and condition monitoring can improve our understanding of the condition and the changes in symptoms, leading to enhanced treatments, including medications and hypothermia. Negligence in routine care can be avoided, and children’s body temperature, heart rate, and respiratory rate can be maintained in the normal range[25]. In addition, targeted emergency nursing is child-centered and includes planned and systematic nursing compared to conventional nursing. During the provision of nursing services, individualized and targeted care to children based on their specific circumstances is essential. This approach aims to enhance the management of pediatric febrile convulsions and decrease the likelihood of complications. By doing so, this approach minimizes potential harm to organ function and neurological well-being caused by prolonged hyperthermia. Additionally, individualized nursing interventions contribute to the maintenance of normal metabolic processes within the body to expedite the recovery process[26].

The rapid onset and development of pediatric febrile convulsions causes fear and tension in the family, resulting in a poor psychological state, which affects their communication with medical and nursing staff and their cooperation with medical treatment. Comprehensive nursing interventions can provide effective first aid and good psychological guidance for the family while caring for children with pediatric febrile convulsions[27]. The application of primary nursing interventions during traditional treatment does not adequately meet the needs of children and parents. In this study, we found that the HAMD and HAMA scores of parents of children in the research group were lower than in the control group after nursing, and the satisfaction of the families in the research group was higher than in the control group. These results indicate that the psychological nursing intervention effectively reduced the negative emotions of parents. Shen et al[28] showed that family recognition of the quality of nursing after febrile convulsions was enhanced after nursing by clustering, which is consistent with our results. We believe that nursing staff should play a crucial role in supporting parents by providing encouragement, comfort, and assistance tailored to their psychological characteristics and level of understanding about the condition. Explaining the causes of febrile convulsions and providing necessary precautions enhance parent confidence and alleviate their anxiety. By doing so, nursing staff can contribute to improving parental satisfaction with the nursing care provided.

In this study, we determined the positive impact of targeted emergency nursing combined with psychological nursing for children with febrile convulsions. Nevertheless, the current study had several limitations. Firstly, this was a single-center study with a small sample size, and the results may be biased. Secondly, as a retrospective study, this study could not follow-up the patients. Thus, the effects of different care regimens on the short-term prognosis of children need further study.

Integration of targeted emergency nursing and psychological nursing proved to be effective in enhancing the satisfaction of children’s families, promoting treatment compliance, facilitating early recovery of clinical symptoms, and improving sleep quality.

| 1. | Laino D, Mencaroni E, Esposito S. Management of Pediatric Febrile Seizures. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Smith DK, Sadler KP, Benedum M. Febrile Seizures: Risks, Evaluation, and Prognosis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:445-450. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mewasingh LD, Chin RFM, Scott RC. Current understanding of febrile seizures and their long-term outcomes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:1245-1249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raghavan VR, Porter JJ, Neuman MI, Lyons TW. Trends in Management of Simple Febrile Seizures at US Children's Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2021;148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, Lagae L, Moshé SL, Peltola J, Roulet Perez E, Scheffer IE, Zuberi SM. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1475] [Cited by in RCA: 2141] [Article Influence: 267.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hon KL, Leung AKC, Torres AR. Febrile Infection-Related Epilepsy Syndrome (FIRES): An Overview of Treatment and Recent Patents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2018;12:128-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Specchio N, Pietrafusa N. New-onset refractory status epilepticus and febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:897-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, Riney K, Samia P, Guerreiro M, Gwer S, Zuberi SM, Wilmshurst JM, Yozawitz E, Pressler R, Hirsch E, Wiebe S, Cross HJ, Perucca E, Moshé SL, Tinuper P, Auvin S. International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: Position paper by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63:1398-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 488] [Cited by in RCA: 448] [Article Influence: 149.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Koh S, Wirrell E, Vezzani A, Nabbout R, Muscal E, Kaliakatsos M, Wickström R, Riviello JJ, Brunklaus A, Payne E, Valentin A, Wells E, Carpenter JL, Lee K, Lai YC, Eschbach K, Press CA, Gorman M, Stredny CM, Roche W, Mangum T. Proposal to optimize evaluation and treatment of Febrile infection-related epilepsy syndrome (FIRES): A Report from FIRES workshop. Epilepsia Open. 2021;6:62-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Harris SA, George AG, Barrett KT, Scantlebury MH, Teskey GC. Febrile seizures lead to prolonged epileptiform activity and hyperoxia that when blocked prevents learning deficits. Epilepsia. 2022;63:2650-2663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu C, Wang H, Zhou L, Xie H, Yang H, Yu Y, Sha H, Yang Y, Zhang X. Sources and symptoms of stress among nurses in the first Chinese anti-Ebola medical team during the Sierra Leone aid mission: A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6:187-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Daniels AL, Morse C, Breman R. Psychological Safety in Simulation-Based Prelicensure Nursing Education: A Narrative Review. Nurse Educ. 2021;46:E99-E102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Subspecialty Group of Neurology; the Society of Pediatrics; Chinese Medical Association. [Expert consensus on the diagnosis and management of febrile seizures(2016)]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2016;54:723-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chang Q, Xia Y, Bai S, Zhang X, Liu Y, Yao D, Xu X, Zhao Y. Association Between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Resident Physicians. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:564815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu Z, Qiao D, Xu Y, Zhao W, Yang Y, Wen D, Li X, Nie X, Dong Y, Tang S, Jiang Y, Wang Y, Zhao J, Xu Y. The Efficacy of Computerized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients With COVID-19: Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e26883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sawires R, Buttery J, Fahey M. A Review of Febrile Seizures: Recent Advances in Understanding of Febrile Seizure Pathophysiology and Commonly Implicated Viral Triggers. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:801321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Heydarian F, Nakhaei AA, Majd HM, Bakhtiari E. Zinc deficiency and febrile seizure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk J Pediatr. 2020;62:347-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Myers KA, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF; ILAE Genetics Commission. Genetic literacy series: genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Epileptic Disord. 2018;20:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Green C. Spiritual Health First Aid for Self-Care: Nursing During COVID-19. J Christ Nurs. 2021;38:E28-E31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sim T, Wang A. Contextualization of Psychological First Aid: An Integrative Literature Review. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2021;53:189-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zeng L, Fan S, Zhou J, Yi Q, Yang G, Hua W, Liu H, Huang H. Undergraduate nursing students' participation in pre-hospital first aid practice with ambulances in China: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;90:104459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Klotz KA, Özcan J, Sag Y, Schönberger J, Kaier K, Jacobs J. Anxiety of families after first unprovoked or first febrile seizure - A prospective, randomized pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;122:108120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Westin E, Sund Levander M. Parent's Experiences of Their Children Suffering Febrile Seizures. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:68-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Jia L, Cai Y, Li W, Chen X. The application experience of all-around nursing care in infantile febrile convulsion. Minerva Pediatr. 2019;71:242-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schoultz M, McGrogan C, Beattie M, Macaden L, Carolan C, Polson R, Dickens G. Psychological first aid for workers in care and nursing homes: systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2022;21:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pham L, Moles RJ, O'Reilly CL, Carrillo MJ, El-Den S. Mental Health First Aid training and assessment in Australian medical, nursing and pharmacy curricula: a national perspective using content analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rice SA, Müller RM, Jeschke S, Herziger B, Bertsche T, Neininger MP, Bertsche A. Febrile seizures: perceptions and knowledge of parents of affected and unaffected children. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:1487-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Shen M, Xu Z, Xu L, Gong X, Xu H, Zhou R, Shen Y. Observation on the effect and nursing quality of cluster nursing in emergency treatment of children with febrile convulsion. Minerva Pediatr (Torino). 2022;74:96-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |