Published online Jan 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i2.431

Peer-review started: November 6, 2023

First decision: December 5, 2023

Revised: December 11, 2023

Accepted: December 27, 2023

Article in press: December 27, 2023

Published online: January 16, 2024

Processing time: 65 Days and 16.8 Hours

The relation between orthodontic treatment and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) is under debate; the management of TMD during orthodontic treatment has always been a challenge. If TMD symptoms occur during orthodontic treat

This case report presents a patient (26-year-old, female) with angle class I, skeletal class II and TMDs. The treatment was a hybrid of clear aligners, fixed appliances and temporary anchorage devices (TADs). After 3 mo resting and treatment on her TMD, the patient’s TMD symptom alleviated, but her anterior occlusion displayed deep overbite. Therefore, the fixed appliances with TAD were used to correct the anterior deep-bite and level maxillary and mandibular deep curves. After the levelling, the patient showed dual bite with centric relation and maximum intercuspation discrepancy on her occlusion. After careful examination of temporomandibular joints (TMJ) position, the stable bite splint and Invisible Mandibular Advancement appliance were used to reconstruct her occlusion. Eventually, the improved facial appearance and relatively stable occlusion were achieved. The 1-year follow-up records showed there was no obvious change in TMJ morphology, and her occlusion was stable.

TMD screening and monitoring is of great clinical importance in the TMD susceptible patients. Hybrid treatment with clear aligners and fixed appliances and TADs is an effective treatment modality for the complex cases.

Core Tip: This article is about the treatment of an adult female patient with skeletal class II and temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). The treatment was a hybrid of clear aligners, fixed appliances and temporary aids devices (TADs). This case report suggested that TMD screening and monitoring is of great clinical importance in the TMD susceptible patients. For these cases, hybrid treatment with clear aligners and fixed appliances and TADs is an effective treatment modality for the complex cases.

- Citation: Lu T, Mei L, Li BC, Huang ZW, Li H. Hybrid treatment of varied orthodontic appliances for a patient with skeletal class II and temporomandibular joint disorders: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(2): 431-442

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i2/431.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i2.431

Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) encompass clinical issues involving the temporomandibular joints (TMJ), associated muscles, and related structures[1], They manifest as limited jaw movement, muscle and joint pain, joint noise during use, myofascial pain, and constraints in jaw opening[2]. Approximately 6% to 12% of the global population experiences TMD symptoms[3], which are more common between ages 20 and 40, with a higher prevalence among women[4,5].

The relation between orthodontic treatment and TMD is under debate; the management of TMD during orthodontic treatment has always been a challenge[6-8]. A recent study has reported that TMD is prevalent (66.67%) during orthodontic treatment and pain-related symptoms are most frequent[9]. If TMD symptoms occur during orthodontic treatment, an immediate pause of orthodontic adjustments is recommended; the treatment can resume when the symptoms are managed and stabilized[10,11].

This study presented a 26-year-old skeletal class II female patient, who experienced TMD (disc displacement of the right joint) after 8-mo clear aligners treatment. After 3-mo resting and TMD treatment, the joint symptoms were relieved but deep bite increased. Fixed appliances with temporary anchorage devices (TADs) were used to open the deep bite. At the late stage of the treatment, a dual-bite was observed; a stable bite splint and an invisible mandibular advancement appliance were used for occlusal reconstruction. After the treatment, the TMD symptoms disappeared, and balanced occlusion and facial appearance were achieved. The 1-year follow-up showed good stability of the treatment result in TMJ and occlusion.

A 26-year-old woman complained of maxillary anterior teeth protrusion and increased overbite.

The patient had no history of TMJ clicking and pain.

The patient denied any history of previous disease.

The patient denied any family history of present illness.

Facial analysis showed a convex profile with a high angle, a protrusive maxilla, and a retrusive mandible (Figure 1A). Intraoral analysis demonstrated that she had maxillary anterior teeth protrusion, class I molar and canine relationships, increased overjet (5 mm), increased overbite (5 mm), and mild crowding in the maxillary arch (2.4 mm) and mandibular arch (2.2 mm) (Figure 2A).

Cephalometric analysis demonstrated a retrognathic mandible and slightly protrusive maxilla, with a skeletal class II relationship (ANB, 6.1°). Her maxillary anterior incisors were slightly proclined (U1-NA, 25.4°), with a hyperdivergent growth pattern (SN-MP, 40.7°); her mandibular incisors were slightly proclined (IMPA, 94.6°) (Figure 3 and Table 1). The panoramic radiograph indicated that there were no third molars and other disorders. In addition, the imaging of bilateral condyles showed no obvious abnormalities (Figure 3C-E). No sign of TMD was observed before the treatment.

| Measurement | Norm | Standard deviations | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment |

| SNA (°) | 83.1 | 3.6 | 85.8 | 83.6 |

| SNB (°) | 79.7 | 3.2 | 80.1 | 80.1 |

| ANB (°) | 3.5 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 3.5 |

| MP-SN (°) | 32.8 | 4.2 | 40.7 | 39.7 |

| Y-axis (°) | 65.3 | 3.2 | 71.4 | 71.2 |

| U1-L1 (°) | 127 | 8.5 | 113.9 | 119.9 |

| U1-SN (°) | 104.6 | 6 | 111.2 | 106.2 |

| U1-NA (mm) | 4.1 | 2.3 | 7.4 | 6.5 |

| U1-NA (°) | 21.5 | 5.9 | 25.4 | 22.5 |

| L1-NB (mm) | 5.7 | 2 | 9.5 | 7.9 |

| L1-NB (°) | 28.1 | 5.6 | 35 | 31.7 |

| FMIA (°) | 57 | 6.8 | 52.8 | 53.3 |

| IMPA (°) | 93.9 | 6.2 | 94.6 | 90.7 |

| FMA (°) | 31.3 | 5 | 34.7 | 32.6 |

| UL-EP (mm) | 1.8 | 1.9 | -0.7 | 1.3 |

| LL-EP (mm) | 2.7 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 |

| Z angle (°) | 71.2 | 4.8 | 61.7 | 61.4 |

This patient was diagnosed with a skeletal class II profile, a high mandibular plane angle, angle class I malocclusion and increased overbite.

To improve the convex profile and retrognathic mandible, correct the deep bite and increased overjet, and establish a balanced and stable facial appearance and occlusion.

The patient requested clear aligners for dental aesthetics. Two options were discussed with the patient and parents. They chose option 2 and refused orthognathic surgery in the consideration of surgical risk and cost.

Option 1. Orthognathic surgery and orthodontic treatment with extraction of two mandibular first premolars. Retraction of the mandibular anterior teeth, followed by bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomy mandibular advancement. Genioplasty can be considered, depending on the patient’s request.

Option 2. Camouflage treatment with clear aligners and extraction of the four first premolars. Use the extraction spaces to retract the anterior teeth to camouflage the skeletal class II. Genioplasty can be considered, depending on the patient’s request. The extraction of upper first premolars and lower second premolars were also discussed with the patient, but considering the biomechanics of clear aligners and anchorage management, extraction of four first premolars were finally chosen.

After the extraction of four first premolars, clear aligners (Align Technology, Santa Clara, California) were delivered to the patient. Each aligner was worn at least 22 h per day for 15 d.

In the 8th month of treatment (Invisalign, #16 of 42), the patient reported pain around the right TMJ (Figure 1B). Orthodontic treatment was immediately paused. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) were taken to evaluate the TMJ. MRI showed anterior disc displacement without reduction (addwoR) in the bilateral TMJ (Figure 4A-D). TMJ radiograph showed the superior surface of the bilateral condyle had a unconsecutive cortex and the spaces of the bilateral TMJ were significantly narrowed (Figure 4E-H). Intraoral examination showed 6 mm overbite and 4 mm overjet in the anterior teeth. The maxillary and mandibular remaining extraction spaces were about 10 mm and 8 mm respectively (Figure 4I-K).

Due to the TMD symptoms, the orthodontic treatment was temperorily paused; physiotherapy and anti-inflammatory therapy were used to improve the TMD. After 3 mo, the TMD symptoms were significantly alleviated, the clear aligners treatment was resumed for 7 month (from Invisalign #16 to #30) (Figure 1C). But the intraoral examination showed a severe anterior deep bite at the 18th months of treatment (Figure 1D).

To correct the deep overbite more efficiently, fixed appliances (Clarity SL, 3M, 0.022 × 0.028-in slot) were used at the 19th month of treatment (Figure 1E). A series of archwires were used, including superelastic nickel-titanium archwires (from 0.014 × 0.025 to 0.018 × 0.025) and 0.018 × 0.025-in stainless steel arch wire with reverse curve of Spee. At the 26th month of treatment, two 8.0 × 1.4 mm mini-screws (Ormco, Orange, Calif) were inserted between the central and lateral incisors to intrude anterior teeth (Figure 1F). The treatment combined with mini-screws intruded the anterior incisor for 6 mo, and the deep overbite was basically resolved (Figure 5).

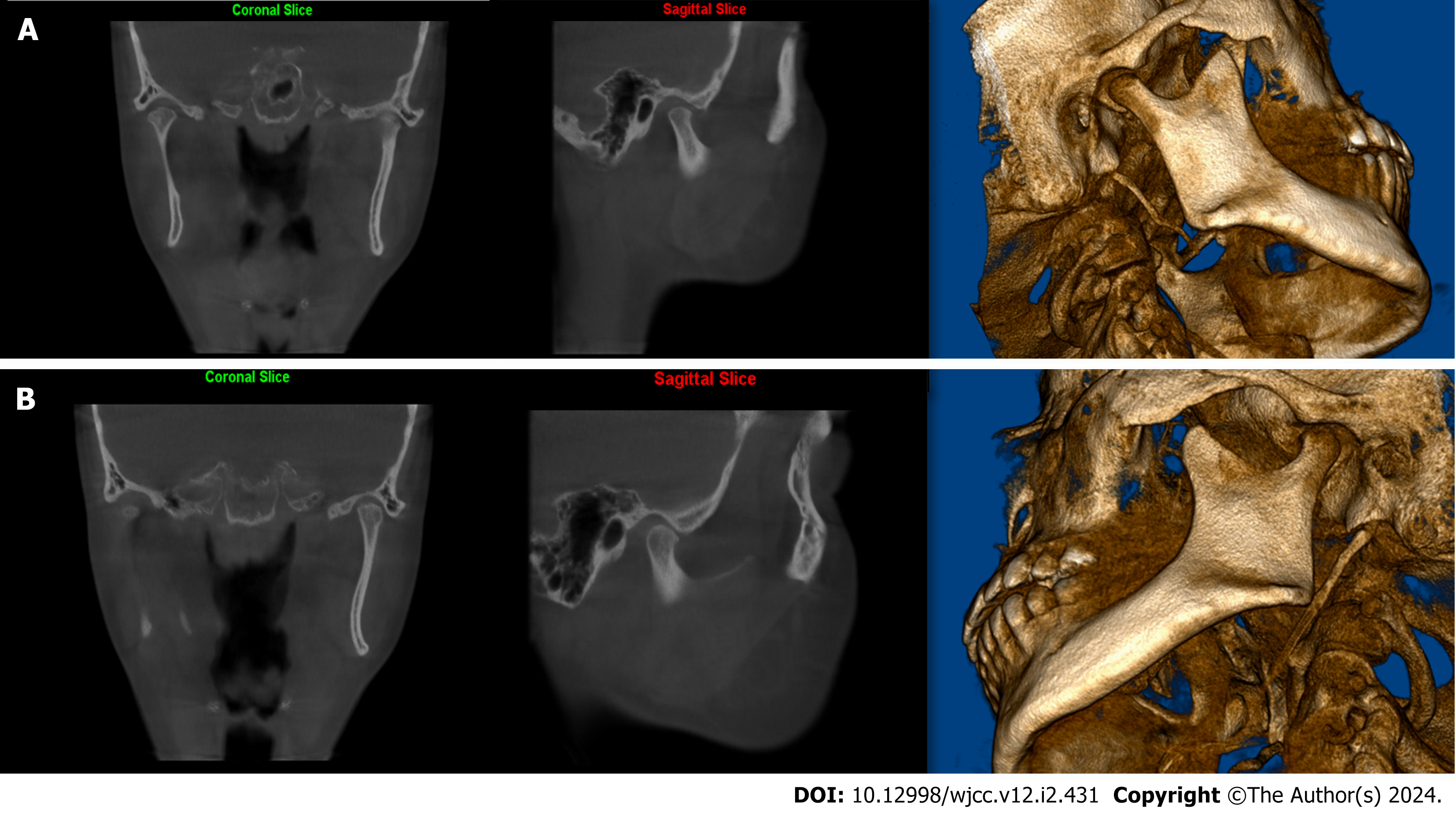

At the 31st month of treatment, the patient developed a dual bite [centric relation (CR)–maximum intercuspation (MI) discrepancy] after the deep bite correction (Figure 6). CBCT images showed when the bilateral condyle was in CR, the bilateral TMJ space was significantly narrowed and the molars were in a severe class II relationship with deep over jet (7 mm). When the bilateral condyle was in MI, the superior and posterior space of the bilateral TMJ were widened and the molars were located in a class I relationship with normal overjet (2 mm). The cephalometric analysis of CR showed that the mandible was retruded and rotated clockwise, resulting in a more severe skeletal class II (ANB, 8.4°) but demonstrated the relative normal ANB angle (3.6°) in MI (Figure 7).

To correct the dual bite, both surgical and conservative options were discussed with the patient. She was against surgery and chose the conservative option with a stable bite splint to stabilize the mandibular position and reduced the load on bilateral TMJ.

At the 38th months of treatment, the fixed appliances were debonded. Due to her tongue thrusting habit, the patient developed anterior open-bite at this stage (Figures 1G and 2B). A stable bite splint was used to identify the appropriate MI position for TMJ, and the patient was educated to cease the tongue thrusting habit (Figure 8). Then the patient reported no discomfort in the bilateral TMJ.

At the 44th month of treatment, the Invisible mandibular advancement appliance (MA) was used to guide the mandible forward to improve the overjet and occlusal reconstruction (Figure 1H).

At the 50th month of treatment, the patient reported no discomfort on TMJ and the overjet was improved. The extraction spaces were closed and the molar relationship became class I (Figure 1I).

The total treatment time was 50 mo, including 38 mo of hybrid treatment of clear aligners and fixed appliances, 6 mo of stable bite splint, and 6 months of MA. Vacuum formed retainers were used for retention.

Post-treatment examination showed favorable improvement in the patient's profile, occlusion, and smiling aesthetics. Intraorally, normal overjet and overbite and a class I molar relationship were achieved (Figures 1I and 2C).

The post-treatment cephalometric analysis showed that the patient's maxillary anterior teeth (U1-NA) were retracted from 25.4° to 22.5°, and the mandibular anterior teeth (IMPA) were uprighted from 94.6° to 90.7°. The ANB angle was reduced from 6.1°to 3.5°. The lower lip to E-line distance were decreased from 3.3 mm to 2.9 mm (Table 1 and Figure 9). The patient treatment process is shown in Figure 10.

Follow-up records after 1 year showed a stable occlusion without relapse (Figure 1J); patient had no TMD symptoms; and the CBCT images showed that the bilateral temporomandibular joint space was significantly improved, and the condyle morphology had no obvious change (Figure 11).

The relationship between orthodontic treatment and TMD has been widely debated. To date, most of the clinical evidence seems to indicate that orthodontic treatment is not directly related to TMDs, and the role of malocclusion in the occurrence and development of TMDs should not be exaggerated[11,12]. For instance, a ten-year longitudinal study showed that joint symptoms during orthodontic treatment should be attributed to differences in age and not to the procedure of orthodontic treatment[13]. Furthermore, patients who experienced orthodontic treatment did not have a higher risk of developing TMD later in life, compared with untreated orthodontic patients[14,15].

In this case, the patient didn’t have TMJ discomfort at the initial diagnosis, but experienced joint pain on the right hand side at the 8th month of treatment when the anterior teeth retraction was only about 1 mm. At the 18th month of treatment, patient’s TMD symptoms were basically alleviated, but unexpected deep bite was found. This can hardly attribute to the possible resorption of bilateral condyles caused by TMD and the decrease in posterior height, which in turn led to mandibular counter clockwise rotation and deeper anterior teeth overbite.

It has been found that there are deficiencies in the correction efficiency with clear aligner therapy compared with traditional fixed appliances, especially for the vertical and torque management[16-18]. The inefficient performance in the torque control during anterior teeth retraction and the Spee’s curve leveling may result in the anterior teeth deep overbite in this case[19,20]. Therefore, for deep bite correction, fixed appliances were also used in this case. In addition, TADs were also used in this case to assist the correction of the deep bite and anterior teeth intrusion[21-23].

After the deep overbite correction, the mandibular deviation and dual bite were observed in this case. The underlining mechanism may be due to some possible condylar resorption and clockwise rotation of the mandible[24,25]. Clinical treatment of condylar resorption has been difficult due to unstable condylar position and persistent changes in the bite[26]. The unstable condylar position can cause confusion during orthodontic evaluation, usually TMJ should be stabilized with occlusal splint prior to orthodontic treatment, which was defined as mandibular reconstruction.

Mandibular reconstruction for dual bite is challenging, especially in adult patients. It could restore deviated mandible and TMJ to their normal position by orthodontic means[27,28]. The basic mechanism of cell biology of occlusal reconstruction is adaptive modification of condyles under exogenous stimulation[29]. At this time, the balance between occlusion, mandibular position and the TMJs needs to be re-established. Under the stimulation of exogenous factors such as stable occlusal splint and invisible MA treatment, the condylar cartilage makes a cell biological response to initiate endochondral osteogenesis, which could be concluded as adaptive modification of the condyle[30]. The treatment of dual bite is often to stabilize and forward mandible to the normal position to promote the modification of condyle adaptation.

Surgery has also been reported to be a good option for the patients who had TMD with occlusal problems[31,32]. The current patient refused any type of surgery, therefore the Invisalign mandibular advancement devices were used to advance the mandible and promote the adaptive modification of the patient's condyles. After the treatment, CBCT images showed that the bilateral TMJ space was significantly improved, and the condyle morphology had no pathological change.

There are limitations in this case. Ideally the patient should be screened for TMD using CBCT and MRI. Since there is uncertainty in the success of occlusal reconstruction, regular imaging could be performed to monitor the morphological change of condyles. If the orthodontic occlusal reconstruction failed, surgical reconstruction could be considered.

TMD screening and monitoring is of great clinical importance in the TMD susceptible patients. Hybrid treatment with clear aligners and fixed appliances and TADs is an effective treatment modality for the complex cases.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Salameh E, Syria S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Ohrbach R, Bair E, Fillingim RB, Gonzalez Y, Gordon SM, Lim PF, Ribeiro-Dasilva M, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, Greenspan JD, Knott C, Maixner W, Smith SB, Slade GD. Clinical orofacial characteristics associated with risk of first-onset TMD: the OPPERA prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2013;14:T33-T50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wadhwa S, Kapila S. TMJ disorders: future innovations in diagnostics and therapeutics. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:930-947. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 466] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, Piccotti F, Ahlberg J, Lobbezoo F. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:453-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 543] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dworkin SF, LeResche L, DeRouen T, Von Korff M. Assessing clinical signs of temporomandibular disorders: reliability of clinical examiners. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;63:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gauer RL, Semidey MJ. Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:378-386. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Murphy MK, MacBarb RF, Wong ME, Athanasiou KA. Temporomandibular disorders: a review of etiology, clinical management, and tissue engineering strategies. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2013;28:e393-e414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Christidis N, Lindström Ndanshau E, Sandberg A, Tsilingaridis G. Prevalence and treatment strategies regarding temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents-A systematic review. J Oral Rehabil. 2019;46:291-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Yap AU, Chen C, Wong HC, Yow M, Tan E. Temporomandibular disorders in prospective orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:377-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shen YH, Chen YK, Chuang SY. Condylar resorption during active orthodontic treatment and subsequent therapy: report of a special case dealing with iatrogenic TMD possibly related to orthodontic treatment. J Oral Rehabil. 2005;32:332-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Michelotti A, Rongo R, D'Antò V, Bucci R. Occlusion, orthodontics, and temporomandibular disorders: Cutting edge of the current evidence. J World Fed Orthod. 2020;9:S15-S18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mohlin B, Axelsson S, Paulin G, Pietilä T, Bondemark L, Brattström V, Hansen K, Holm AK. TMD in relation to malocclusion and orthodontic treatment. Angle Orthod. 2007;77 542-548 [PMID:17465668 DOI: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077. |

| 13. | Dibbets JM, van der Weele LT. Orthodontic treatment in relation to symptoms attributed to dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint. A 10-year report of the University of Groningen study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;91:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Egermark I, Magnusson T, Carlsson GE. A 20-year follow-up of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and malocclusions in subjects with and without orthodontic treatment in childhood. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:109-115. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Henrikson T, Nilner M, Kurol J. Signs of temporomandibular disorders in girls receiving orthodontic treatment. A prospective and longitudinal comparison with untreated Class II malocclusions and normal occlusion subjects. Eur J Orthod. 2000;22:271-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buschang PH, Shaw SG, Ross M, Crosby D, Campbell PM. Comparative time efficiency of aligner therapy and conventional edgewise braces. Angle Orthod. 2014;84:391-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Weir T. Clear aligners in orthodontic treatment. Aust Dent J. 2017;62 Suppl 1:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dai FF, Xu TM, Shu G. Comparison of achieved and predicted tooth movement of maxillary first molars and central incisors: First premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:679-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jaber ST, Hajeer MY, Sultan K. Treatment Effectiveness of Clear Aligners in Correcting Complicated and Severe Malocclusion Cases Compared to Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e38311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ke Y, Zhu Y, Zhu M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alshammery D, Alqhtani N, Alajmi A, Dagriri L, Alrukban N, Alshahrani R, Alghamdi S. Non-surgical correction of gummy smile using temporary skeletal mini-screw anchorage devices: A systematic review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2021;13:e717-e723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Atalla AI, AboulFotouh MH, Fahim FH, Foda MY. Effectiveness of Orthodontic Mini-Screw Implants in Adult Deep Bite Patients during Incisor Intrusion: A Systematic Review. Contemp Clin Dent. 2019;10:372-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bardideh E, Tamizi G, Shafaee H, Rangrazi A, Ghorbani M, Kerayechian N. The Effects of Intrusion of Anterior Teeth by Skeletal Anchorage in Deep Bite Patients; A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomimetics (Basel). 2023;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Burstone CJ. Diagnosis and treatment planning of patients with asymmetries. Semin Orthod. 1998;4:153-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Owtad P, Potres Z, Shen G, Petocz P, Darendeliler MA. A histochemical study on condylar cartilage and glenoid fossa during mandibular advancement. Angle Orthod. 2011;81:270-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee GH, Park JH, Lee SM, Moon DN. Orthodontic Treatment Protocols for Patients with Idiopathic Condylar Resorption. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019;43:292-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tingey EM, Buschang PH, Throckmorton GS. Mandibular rest position: a reliable position influenced by head support and body posture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:614-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | De Stefano AA, Guercio-Monaco E, Hernández-Andara A, Galluccio G. Association between temporomandibular joint disc position evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging and mandibular condyle inclination evaluated by computed tomography. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47:743-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Owtad P, Park JH, Shen G, Potres Z, Darendeliler MA. The biology of TMJ growth modification: a review. J Dent Res. 2013;92:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Shen G, Darendeliler MA. The adaptive remodeling of condylar cartilage---a transition from chondrogenesis to osteogenesis. J Dent Res. 2005;84:691-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang H, Xue C, Luo E, Dai W, Shu R. Three-dimensional surgical guide approach to correcting skeletal Class II malocclusion with idiopathic condylar resorption. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:399-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chigurupati R, Mehra P. Surgical Management of Idiopathic Condylar Resorption: Orthognathic Surgery Versus Temporomandibular Total Joint Replacement. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2018;30:355-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |