Published online Jul 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i19.3918

Revised: April 25, 2024

Accepted: May 9, 2024

Published online: July 6, 2024

Processing time: 143 Days and 8.2 Hours

Amyloidosis is a rare disorder that can be classified into various types, and the most common type is the systemic light chain type. The prognosis of this disease is extremely poor. In general, amyloidosis mainly affects the kidneys and heart and manifests as abnormal proliferation of clonal plasma cells. Cases in which the liver is the primary organ affected by amyloidosis, as in this report, are less common in clinical practice.

A 62-year-old man was admitted with persistent liver dysfunction of unknown cause and poor treatment outcomes. His condition persisted, and he developed chronic liver failure, with severe cholestasis in the later stage that was gradually accompanied by renal injury. Ultimately, he was diagnosed with hepatic amy

Hepatic amyloidosis rarely occurs in the clinic, and liver biopsy and pathological examination can assist in the accurate and effective diagnosis of this condition.

Core Tip: We report a rare case of a patient who was admitted with persistent liver dysfunction and developed chronic liver failure and severe cholestasis. Primary systemic amyloidosis with only symptoms and signs of hepatic involvement is rare and presents a diagnostic challenge. The patient was ultimately diagnosed with hepatic amyloidosis through liver biopsy and pathological examination by Congo red staining. The patient requested symptomatic treatment with hepatic protective drugs and refused stem cell transplantation or chemotherapy. The patient has a poor prognosis.

- Citation: Chen Y, Peng J, Wang Y, Xiao LH, Liu F, Wei YB, Wu XF, Wang LW. Hepatic amyloidosis in a patient with chronic liver failure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(19): 3918-3924

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i19/3918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i19.3918

Amyloidosis is a clinical disease that is characterized by the extracellular deposition of fibrillar proteins in one or more organs. The most common form of systemic amyloidosis is amyloidosis (light chain) (AL), which accounts for approximately 70% of all cases[1]. Primary systemic amyloidosis is usually a systemic condition that affects multiple organs, including the heart, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, skeletal muscles, and other organs. Signs of single-organ involvement have been observed in only in a few cases of systemic amyloidosis[2].

Primary systemic amyloidosis with symptoms and signs of hepatic involvement alone is rare and presents a diagnostic challenge. Here, we report the case of an elderly male patient with persistent unexplained liver dysfunction, poor treatment outcomes, and progression to chronic liver failure; this patient was diagnosed with hepatic amyloidosis through liver biopsy and pathological examination. This patient presented with systemic AL amyloidosis with liver involvement as the unique manifestation.

A 62-year-old man who repeatedly experienced fatigue, nausea, poor appetite, and yellow urine over the previous two months was admitted to our hospital in November 2023. Over the previous month, yellow staining had appeared on the skin and sclera, and it has gradually worsened.

The patient presented with unexplained liver dysfunction during a physical examination six months prior. After taking liver-protective drugs, there was a slight improvement in indicators of liver function. However, in the two months prior to admission, liver function abnormalities continued to worsen, with symptoms and signs of nausea, poor appetite and jaundice, which could not be improved through targeted treatment with liver-protective drugs. Moreover, the patient’s weight was significantly decreased compared to before disease onset.

The patient had a history of hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia and type 2 diabetes for 4 years and was treated with traditional Chinese medicine.

The patient presented with no obvious family history of disease.

The patient’s vital signs were stable. The sclera and skin were stained yellow. Liver palms or spider nevi were not observed. No abnormal signs were detected during cardiac or pulmonary auscultation. The abdomen was flat and soft, without tenderness or rebound pain. Both lower limbs had mild edema.

Laboratory investigations revealed clearly abnormal liver function, hypoalbuminemia and hyperbilirubinemia. Hepatitis A antibodies, hepatitis B markers, hepatitis C antibodies, hepatitis E antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies and extractable nuclear antigen were all negative. The levels of ceruloplasmin and Procalcitonin that were detected were normal (Table 1).

| Parameter | Patient's value | Reference value |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 71 U/L | 9-50 U/L |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 102 U/L | 15-40 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 393 U/L | 45-125 U/L |

| γ-Glutamate transpeptidase | 931 U/L | 10-60 U/L |

| Total bile acid | 81.92 µmol/L | 0-10 µmol/L |

| Serum albumin | 34.7 g/L | 40-55 g/L |

| Total bilirubin | 113 µmol/L | 0-23 µmol/L |

| Direct bilirubin | 93.4 µmol/L | 0-8 µmol/L |

| Hepatitis A antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis B markers | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis C antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Hepatitis E antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Extractable nuclear antigen | Negative | Negative |

| Ceruloplasmin | 33.4 mg/dL | 22-58 mg/dL |

| Procalcitonin | 0.132 ng/mL | 0-0.05 ng/mL |

| Urinary immunoglobulin κ-light chain | 0.148 g/L | 0-0.02 g/L |

| Urinary immunoglobulin λ-light chain | 0.05 g/L | 0-0.05 g/L |

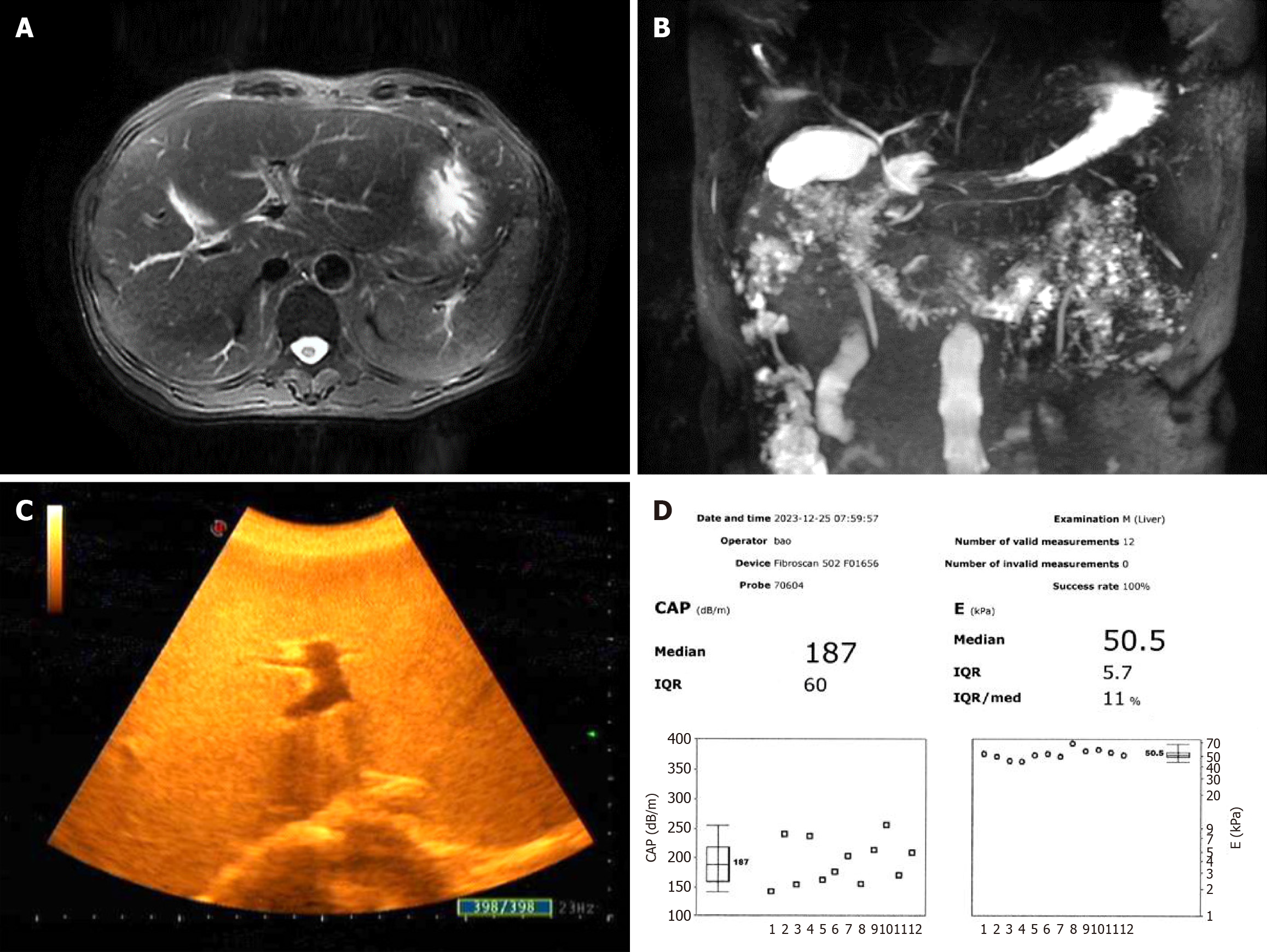

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging revealed fatty liver, possible bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, a left renal cyst, and splenomegaly. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography results were normal. Abdominal B-mode ultrasound revealed cirrhosis, a slightly enlarged liver, a thickened gallbladder wall, multiple polyps in the gallbladder, a small cyst in the left kidney, and a small stone in the left kidney. FibroScan showed that the liver vibration controlled transient elastography value was obviously increased to 50.5 kPa (normal value < 7.3 kPa), and the controlled attenuation parameter value for the quantitative evaluation of hepatic fat content was 187 dB/m (normal value < 223 dB/m) (Figure 1).

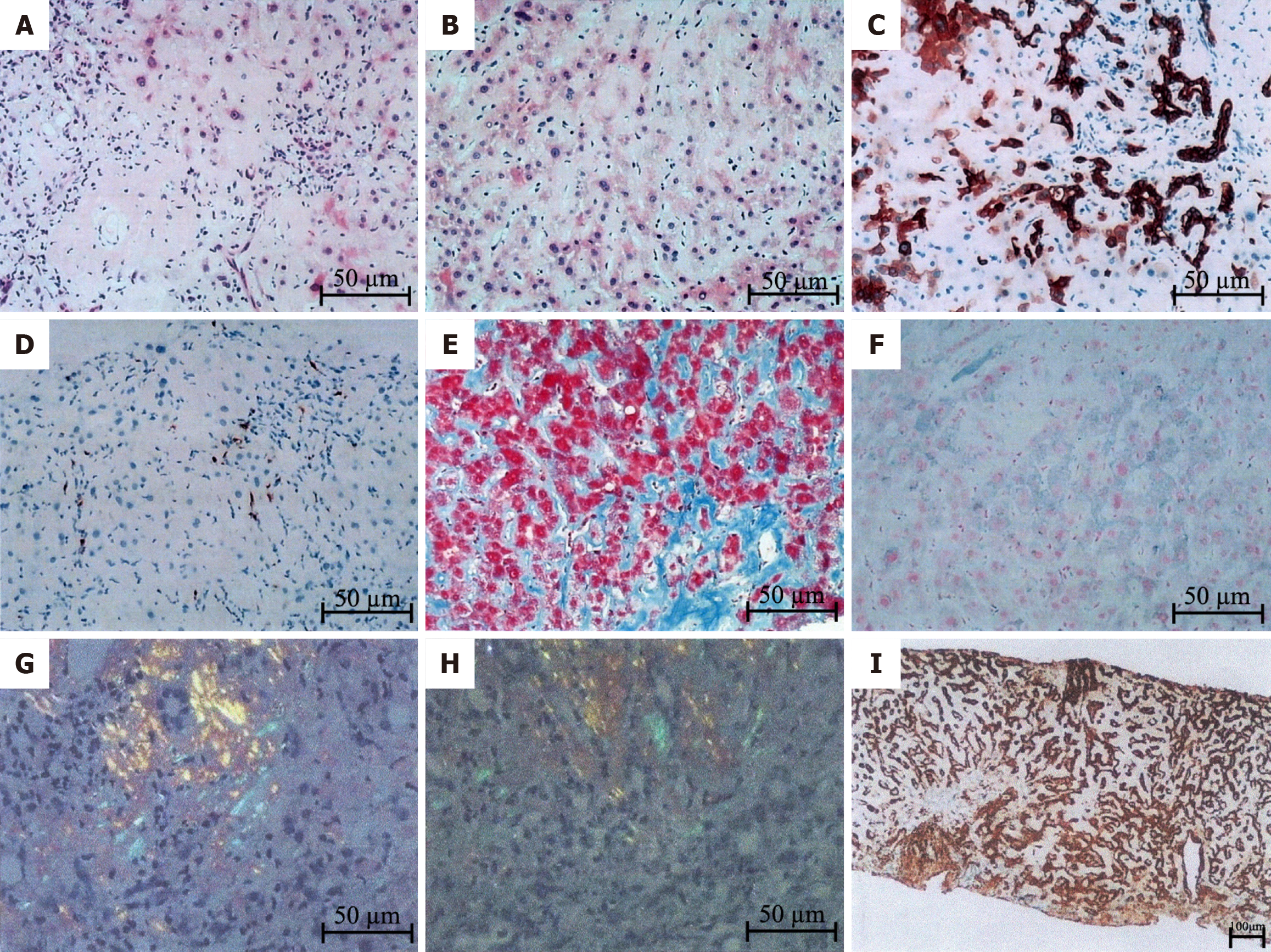

The patient underwent liver biopsy after providing informed consent, and the results of the pathological examination are reported as follows (Figure 2).

Under the microscope, the following histological changes in the liver were observed. Diffuse deposition of pale pink homogeneous material was observed in the perisinusoidal space, hepatocyte space, and subendothelial space of the central vein. Stenosis of the hepatic sinuses, partial atrophy of liver cells, and the presence of cholestatic pigment granules in some hepatocytes were observed. Dilation and cholestasis of the bile ducts were also observed, with biliary emboli. The portal area was expanded to varying degrees, with deposition of pale pink staining material around the blood vessels and infiltration of a substantial number mixed inflammatory cells.

The immunohistochemical results revealed positive CK7 and CK19 staining in the bile duct epithelium. Approximately 90% of liver cells were positive for CK7. C68 staining revealed a small number of activated Kupffer cells. α-SMA staining revealed a large number of activated hepatic stellate cells. Positive staining for MUM1 was observed in a few plasma cells. IgG staining was positive (light pink staining), while IgG4 staining was negative. For amyloid-like substances, κ, λ, nonspecific GEL, TTR, nonspecific APOA-II, APOA-IV, and LECT2 staining was positive, while AA and APOA-I staining was negative.

The results of special staining were as follows. Masson and Sirius crimson staining revealed diffuse deposition of homogeneous material around the sinusoids and blood vessels. Mesh staining revealed the presence of a hepatic plate network scaffold, with positive PAS staining and negative D-PAS staining. Prussian blue staining showed the deposition of iron particles in liver cells and Kupffer cells. Copper staining was negative. Polarized light microscopy revealed positive Congo red and oxidized Congo red staining.

The mass spectrometry typing results of amyloidosis revealed a high abundance of the amyloid chaperone proteins ApoE and SAP. Among the proteins that are currently known to be related to typing, the relative abundance of the Ig κ protein was the highest, which suggested that the subtype of amyloidosis in this patient was AL κ.

The final diagnosis was hepatic amyloidosis with AL (κ subtype).

The patient requested symptomatic treatment with hepatoprotective drugs, such as glutathione, S-adenosylmethionine, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate, and bicyclol, and refused stem cell transplantation or chemotherapy.

Considering that the immunohistochemical results showed positive TTR, APOA-IV and LECT2 staining and negative AA staining, it was recommended that the patient undergo further analysis of amyloid components by microdissection mass spectrometry, but the patient refused. The patient's liver function continued to deteriorate. At the time when this case report was written, the patient was still in a state of high jaundice, and there were abnormalities in the glomerular filtration rate and urinary protein indicators, with a progressively worsening trend. It was suggested that the patient undergo further bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry analysis, blood and urine immunoglobulin testing, and fixed electrophoresis, but the patient refused. The patient has a poor prognosis.

Amyloidosis occurs due to the extracellular deposition of toxic fibrillar amyloid proteins, and amyloidosis is classified according to chemical analysis of clinical amyloid entities. The four most prevalent deposition types are AL (A represents amyloid protein, and L represents the light chain of immunoglobulin), AA (amyloid serum A protein), ATTR (amyloid transport protein transthyretin), and β2-MG (dialysis-related amyloidosis involving beta-2 microglobulin)[1]. AL amyloidosis is commonly considered a plasma cell disease that is caused by a usually small and slowly proliferating plasma cell clone in the bone marrow. This clone produces nonfunctional immunoglobulin, which misfolds to form β-pleated amyloid fibrils[3]. Amyloidosis is typically a systemic disease, with only 10%-20% of primary amyloidosis patients presenting with single-organ involvement. The most common form of all types of systemic amyloidosis is AL amyloidosis, which mostly affects elderly males. The organs that are mainly affected are the kidneys and heart, while damage to other organs is rare. The symptoms and signs of patients with this disease are nonspecific, and the condition is determined by the affected organs and systems, often resulting in organ enlargement and dysfunction[4]. Hepatic involvement is rarely the only manifestation of primary systemic amyloidosis. Hepatic involvement is characterized by liver disease that leads to an enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) and abnormal liver function, resulting in cholestasis. This condition is usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms, such as weight loss[5]. Our case report describes a patient with systemic AL amyloidosis and liver involvement as the sole manifestation. The patient's initial symptoms were nonspecific and characterized by liver dysfunction, hepatomegaly, and mild jaundice, posing a diagnostic challenge. When diagnosis in the early stages of the disease is delayed, progressive organ dysfunction occurs in these patients, ultimately leading to chronic liver failure with severe cholestasis. Therefore, invasive diagnostic procedures, such as liver biopsy, are usually required at this time.

Tissue biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis, but biomarkers and imaging data may only have suggestive significance[6]. Before biopsy, extensive diagnostic tests are usually needed, including but not limited to the following: serum-free light chain assay, immunofixed serum and urine protein electrophoresis, whole blood count, liver and kidney function testing, 24-h urine protein level tests and quantitative immunoglobulin level tests[3]. Congo red is the gold standard tissue staining technique for that is used the diagnosis of amyloidosis. After staining with Congo red, a tissue sample should display green birefringent fibrils under a polarizing microscope[7]. The biopsy site can be a terminal organ that is suspected of having fibrillar deposition or it can be a substitute tissue for areas where amyloid protein is frequently deposited, such as abdominal fat, bone marrow, or salivary glands[8]. If the substitute site biopsy is negative but there is persistent suspicion of AL amyloidosis in clinical practice, target organ biopsy should be performed[9]. If amyloid protein is found in the biopsy sample, the type of amyloid protein should be determined to achieve a complete diagnosis. Several methods can be used for amyloid protein typing, including immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy, and laser microdissection based on mass spectrometry for proteomic analysis[8]. AL amyloidosis is closely related to monoclonal plasma cell proliferative diseases, especially multiple myeloma. A previous study showed that approximately 10% of AL amyloidosis patients may have a potential monoclonal plasma cell disorder[10]. Therefore, the combination of target organ biopsy and bone marrow biopsy can be used to evaluate potential plasma cell abnormalities and improve diagnostic sensitivity[11]. In our patient, pathological examination of the liver biopsy revealed positive Congo red staining, which clearly suggested liver amyloidosis. The lesions were mostly located in the hepatic disse space, hepatocellular interstitium, bile duct, and blood vessel walls. Further mass spectrometry typing revealed the AL κ subtype. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with hepatic amyloidosis with AL (κ subtype).

The current goal for treating AL amyloidosis is to reduce the levels of amyloid immunoglobulin-free light chain as soon as possible through the use of the most effective anti-plasma cell therapy as well as supportive care for managing secondary organ dysfunction or failure. The treatment center focuses on reducing the dysfunction caused by amyloid protein deposition in organs. At present, there is no specific drug for treating this disease. In the early 1990s, due to previous success in the treatment of multiple myeloma, high-dose intravenous injections of melphalan and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDM/SCT) were developed for the treatment of AL amyloidosis[12]. However, only 20%-30% of patients, or even fewer, newly diagnosed with AL amyloidosis are eligible for SCT treatment. Therefore, SCT should be the first choice for eligible patients who may experience greater hematological and organ improvement. For patients who are ineligible for SCT, a daratumumab, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (Dara-CyBorD) regimen can be chosen for treatment. Several studies have shown that induction therapy based on bortezomib is feasible and has high efficacy[13]. However, while induction therapy prior to SCT may benefit some patients, others may experience worsening of clinical symptoms that prevent them from receiving SCT treatment[14]. Therefore, after confirming the diagnosis of AL amyloidosis, all patients should be evaluated to assess their suitability for autologous SCT. SCT is typically provided to individuals under the age of 70, but careful selection of patients over the age of 70 can also yield good results[15].

Unfortunately, in this report, the patient requested symptomatic treatment with hepatic protective drugs, such as glutathione, S-adenosylmethionine, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate, and bicyclol, and refused stem cell transplantation or chemotherapy due to personal family reasons. In addition, the use of steroid drugs was considered for this patient. However, after the side effects of steroids and the inability to guarantee their exact efficacy for treating hepatic amyloidosis were described in detail to the patient, the patient refused steroids. The patient's liver function continued to deteriorate; he was still in a state of high jaundice, and there were abnormalities in the glomerular filtration rate and urinary protein indicators, with a progressive worsening trend. It was suggested that the patient undergo further bone marrow biopsy, flow cytometry analysis, blood and urine immunoglobulin testing, and fixed electrophoresis, but the patient still refused. The patient has a poor prognosis.

In summary, hepatic amyloidosis is a rare disease that typically presents with vague, nonspecific manifestations and a poor prognosis. This rare condition presents a significant diagnostic challenge. Liver biopsy and pathological examination can assist in the accurate and effective diagnosis of this condition. A tissue biopsy stained with Congo red can reveal deposition of amyloid protein, and mass spectrometry can confirm the type; together, these methods can confirm the diagnosis of the disease. AL amyloidosis is a fatal disease that requires systematic treatment to prevent amyloid deposition in other organs and progressive organ failure. The current first-line induction therapy is the combination of daratumumab, cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (Dara-CyBorD). Patients who meet these criteria should undergo autologous stem cell transplantation after high-dose melphalan therapy (HDM/SCT).

| 1. | Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A. Systemic Amyloidosis Recognition, Prognosis, and Therapy: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2020;324:79-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 35.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kottavadakkeel N, Rajaram A. Hepatic Involvement as the Sole Presentation of Systemic Amyloid Light Chain (AL) Amyloidosis: A Diagnostic Challenge. Cureus. 2023;15:e47310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Gertz MA. Immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis: 2020 update on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:848-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Duve RJ, Moga TG, Yang K, Mahl TC, Dove E. Hepatic Amyloidosis With Multiorgan Involvement. ACG Case Rep J. 2023;10:e00999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhao L, Ren G, Guo J, Chen W, Xu W, Huang X. The clinical features and outcomes of systemic light chain amyloidosis with hepatic involvement. Ann Med. 2022;54:1226-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Elsayed M, Usher S, Habib MH, Ahmed N, Ali J, Begemann M, Shabbir SA, Shune L, Al-Hilli J, Cossor F, Sperry BW, Raza S. Current Updates on the Management of AL Amyloidosis. J Hematol. 2021;10:147-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kumar SK, Callander NS, Adekola K, Anderson LD Jr, Baljevic M, Campagnaro E, Castillo JJ, Costello C, D'Angelo C, Devarakonda S, Elsedawy N, Garfall A, Godby K, Hillengass J, Holmberg L, Htut M, Huff CA, Hultcrantz M, Kang Y, Larson S, Lee HC, Liedtke M, Martin T, Omel J, Rosenberg A, Sborov D, Valent J, Berardi R, Kumar R. Systemic Light Chain Amyloidosis, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:67-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wisniowski B, Wechalekar A. Confirming the Diagnosis of Amyloidosis. Acta Haematol. 2020;143:312-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Palladini G, Milani P, Merlini G. Management of AL amyloidosis in 2020. Blood. 2020;136:2620-2627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hanumanthu V, Thakur V, Chatterjee D, Vinay K. Periocular cutaneous amyloidosis in multiple myeloma. QJM. 2021;114:603-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fotiou D, Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E. Systemic AL Amyloidosis: Current Approaches to Diagnosis and Management. Hemasphere. 2020;4:e454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanchorawala V, Wright DG, Seldin DC, Dember LM, Finn K, Falk RH, Berk J, Quillen K, Skinner M. An overview of the use of high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell transplantation for the treatment of AL amyloidosis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:637-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kastritis E, Palladini G, Minnema MC, Wechalekar AD, Jaccard A, Lee HC, Sanchorawala V, Gibbs S, Mollee P, Venner CP, Lu J, Schönland S, Gatt ME, Suzuki K, Kim K, Cibeira MT, Beksac M, Libby E, Valent J, Hungria V, Wong SW, Rosenzweig M, Bumma N, Huart A, Dimopoulos MA, Bhutani D, Waxman AJ, Goodman SA, Zonder JA, Lam S, Song K, Hansen T, Manier S, Roeloffzen W, Jamroziak K, Kwok F, Shimazaki C, Kim JS, Crusoe E, Ahmadi T, Tran N, Qin X, Vasey SY, Tromp B, Schecter JM, Weiss BM, Zhuang SH, Vermeulen J, Merlini G, Comenzo RL; ANDROMEDA Trial Investigators. Daratumumab-Based Treatment for Immunoglobulin Light-Chain Amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:46-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 89.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanchorawala V, Boccadoro M, Gertz M, Hegenbart U, Kastritis E, Landau H, Mollee P, Wechalekar A, Palladini G. Guidelines for high dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation for systemic AL amyloidosis: EHA-ISA working group guidelines. Amyloid. 2022;29:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sidiqi MH, Aljama MA, Muchtar E, Buadi FK, Warsame R, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Dingli D, Leung N, Gonsalves WI, Kapoor P, Kourelis TV, Hogan WJ, Kumar SK, Gertz MA. Autologous Stem Cell Transplant for Immunoglobulin Light Chain Amyloidosis Patients Aged 70 to 75. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:2157-2159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |