Published online Jun 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3615

Revised: April 22, 2024

Accepted: April 25, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2024

Processing time: 96 Days and 23.9 Hours

Effective bowel cleansing is essential for a successful colonoscopy. Laxatives, such as polyethylene glycol, are commonly used for bowel preparation. Vomiting is a frequent complication during bowel preparation, and forceful vomiting can po

A 38-year-old man with a history of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mell

Despite its rarity, pharyngeal perforation should be considered a potential com

Core Tip: Vomiting is a common complication of bowel preparation. Forceful vomiting can lead to esophageal perforation, as reported in several prior cases. However, pharyngeal perforation during bowel preparation has not been reported previously. Here, we present a rare case of pharyngeal perforation caused by forceful vomiting during bowel preparation. The perforation was resolved with conservative medical management. Pharyngeal perforation should be considered a potential complication during bowel preparation for colonoscopy when sudden pain in the neck, throat, and anterior chest occurs following forceful vomiting. Early recognition and prompt management are important in vomiting-induced pharyngeal perforation during bowel preparation.

- Citation: Kim G, Lee WH, Kang S, Moon JR, Lee YS, Son JH, Kim NH, Kim JW. Vomiting-induced pharyngeal perforation during bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(18): 3615-3621

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i18/3615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3615

Effective bowel cleansing is crucial for a successful colonoscopy. Inadequate bowel preparation can lead to cecal in

High-volume polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions are widely used because of their effectiveness in minimizing electrolyte imbalance. It is notably beneficial, as it does not lead to significant physiological changes, such as alterations in body weight, vital signs, serum electrolytes, and blood chemistry. Therefore, it is considered suitable for patients with renal failure, congestive heart failure, or liver cirrhosis[1,2].

Awareness of the potential adverse events associated with bowel preparation is essential, including the risk of aspiration, abdominal pain, and nausea with or without vomiting[3]. Forceful vomiting during bowel preparation can cause upper gastrointestinal tract injuries; cases of esophageal injuries, including Mallory-Weiss syndrome and Boerhaave’s syndrome, following ingestion of PEG solutions have been reported[4-6]. To the best of our knowledge, pharyngeal perforation during bowel preparation has not been previously reported.

A 38-year-old man complained of sudden pain in the neck, throat, and anterior chest after several attacks of forceful vomiting during bowel preparation for colonoscopy.

The patient was admitted for evaluation of recurrent abdominal pain. Upon admission, his vital signs were stable, and chest and abdominal radiographs showed no abnormalities. A colonoscopy was planned for further evaluation. A 4 L high-volume PEG solution, which is considered safe for patients with severe renal insufficiency, was administered for bowel preparation in a split-dose regimen, defined as the administration of PEG in two separate doses. After consuming the second 2 L dose, the patient experienced several episodes of forceful vomiting and sudden pain in the neck, throat, and anterior chest. Initially, the patient did not disclose these episodes or the ensuing pain to the medical staff. However, as the discomfort intensified, he promptly notified the medical team. Additionally, the patient denied dyspnea.

The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Additionally, the patient was undergoing outpatient treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. For diabetes mellitus, the treatment regimen consisted of daily subcutaneous injection of insulin degludec, oral administration of linagliptin 5 mg once daily, and oral repaglinide 2 mg once daily. In managing hypertension, the patient was prescribed oral amlodipine 10 mg once daily and carvedilol 12.5 mg once daily. For dyslipidemia, the patient received oral atorvastatin 20 mg once daily. For irritable bowel syndrome management, the prescribed regimen included oral trimebutine 100 mg three times daily and Lacidofil® (probiotic Lactobacillus; Pharmbio Korea Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) one capsule twice daily. Given the patient’s complex medical profile due to multiple underlying diseases and ongoing dialysis, he was admitted for eva

Three years prior to admission, he underwent colonoscopy at our hospital, revealing no remarkable abnormalities apart from a 3 mm-sized Is adenomatous polyp in the rectum, which was removed endoscopically.

The patient had no history of drinking, smoking, or drug use. The patient’s father had diabetes mellitus and hyper

His blood pressure was 132/68 mmHg, pulse rate was 84/min, and body temperature was 36.9℃. Physical examination revealed crepitus under the skin of the neck and anterior chest on palpation, indicating subcutaneous emphysema.

The laboratory data upon admission were as follows: white blood cell count 8950/mm3, hemoglobin 9.5 mg/dL, platelet count 157000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase 11 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 10 U/L, total bilirubin 0.63 mg/dL, creatinine 9.43 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 0.4 mg/dL, sodium 136 mEq/L, potassium 5.1 mEq/L, amylase 66 U/L, and lipase 36 U/L.

On the day of the event, the laboratory data were as follows: White blood cell count 10650/mm3, hemoglobin 9.0 mg/dL, platelet count 160000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase 10 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 7 U/L, total bilirubin 0.69 mg/dL, creatinine 9.05 mg/dL, C-reactive protein 0.8 mg/dL, sodium 133 mEq/L, and potassium 4.3 mEq/L.

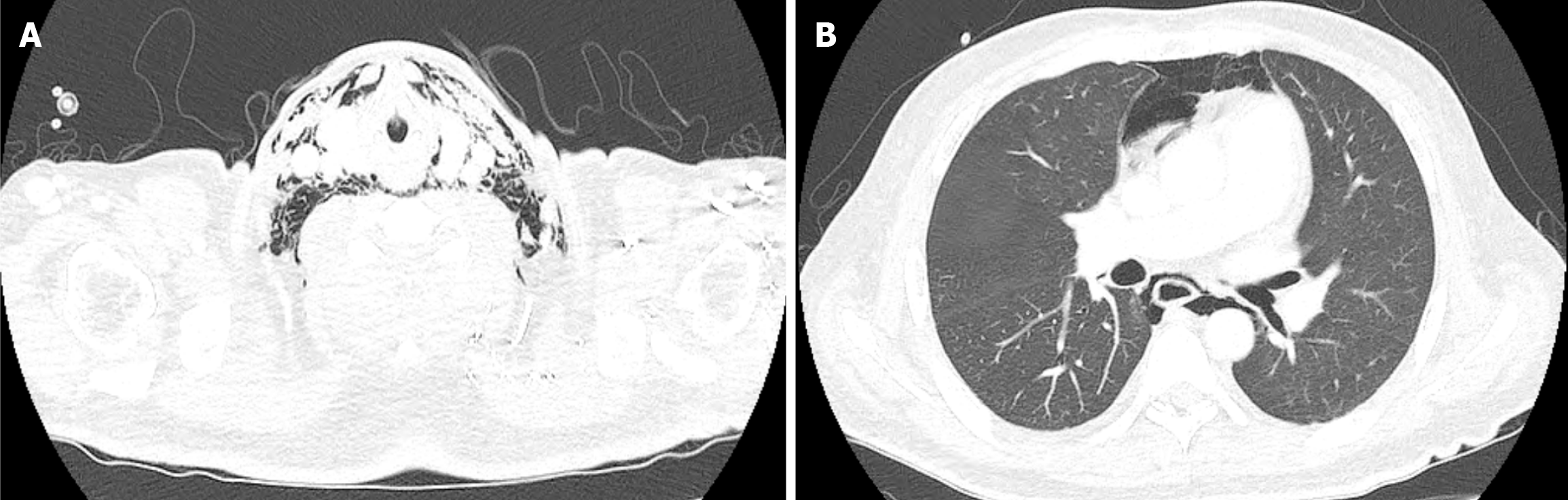

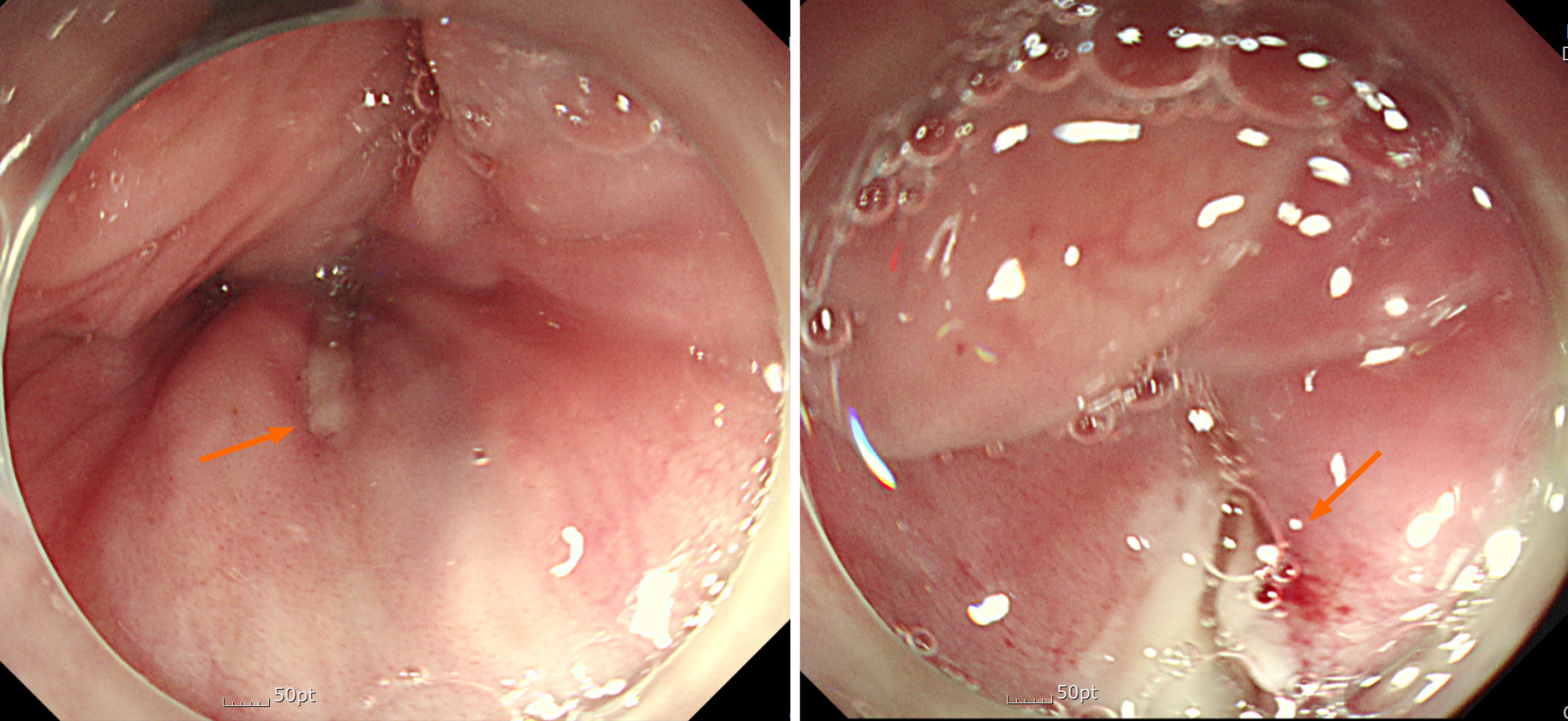

Immediate chest radiography was performed, followed by chest computed tomography (Figure 1), which identified pneumomediastinum and emphysema in the soft tissue of the neck and chest. While no definitive esophageal injury was evident on the chest computed tomography scan, suspicion of esophageal perforation prompted a consultation with a thoracic surgeon. It was determined that upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was necessary to identify any esophageal defects, and preparations for emergency surgery were initiated. Endoscopy revealed a linear focal wall defect in the posterior pharynx immediately above the upper esophageal sphincter (Figure 2), presenting limited space for endoscopic interventions, such as endoscopic clipping. Additionally, the patient’s persistent retching further complicated the man

Given the endoscopic findings, a final diagnosis of pharyngeal perforation was made.

Conservative medical management was chosen after consultation with a thoracic surgeon and otolaryngologist, considering the patient's mild symptoms, stable vital signs, and small lesion size. Oral intake was prohibited and parenteral nutritional support was initiated. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor were administered along with oxygen supplementation via a nasal prong.

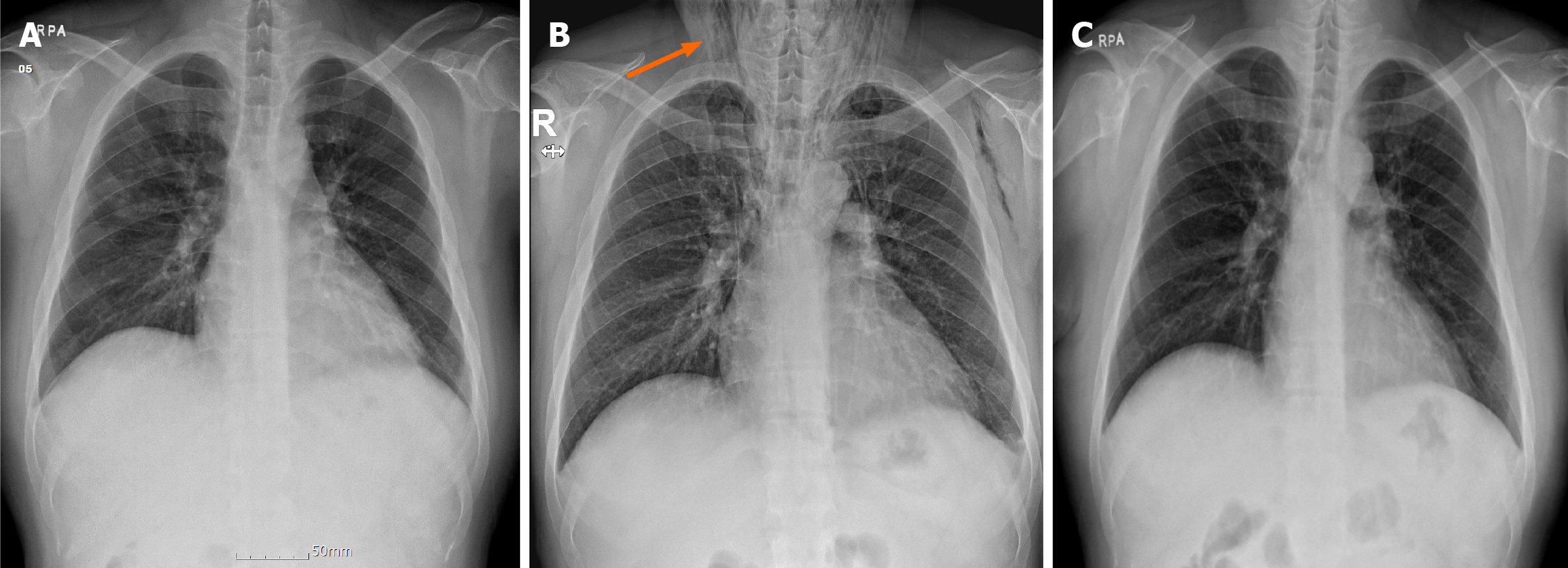

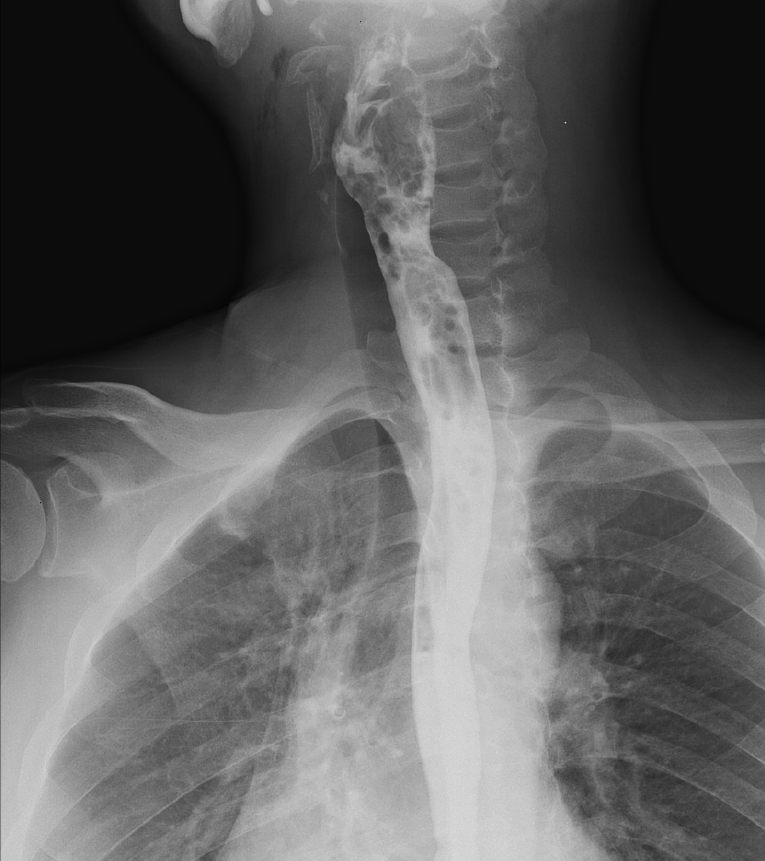

Daily physical and radiographic examinations revealed gradual absorption of the subcutaneous emphysema. Serial chest radiographs are shown in Figure 3. Six days after the perforation, follow-up endoscopy revealed a healed pharyngeal ulcer, and esophagography confirmed no leakage of the contrast medium (Figure 4). Subsequently, an oral diet was administered. The patient was discharged from hospital two weeks after the perforation. He was followed up in the outpatient clinic and continued to receive medications for irritable bowel syndrome. Further colonoscopy was not performed due to the patient’s refusal.

Colonoscopy is a widely performed procedure for the screening and surveillance of colorectal neoplasms and for the diagnosis and treatment of various colonic diseases[7]. Although complications occurring during or after colonoscopy procedures have been well documented[8,9], those arising from pre-colonoscopy bowel preparations have not been elucidated. A recent large-population retrospective study primarily analyzing the complications of bowel preparation, was published in 2022[3]. A total of 9962 patients underwent bowel preparation for colonoscopy, and 33.69% reported adverse events during the bowel preparation period. The most frequent symptom was vomiting, reported by 667 patients, and blood in the vomit was observed in 93 patients; among these, the most common cause was Mallory-Weiss syndrome, identified in 25 patients. Because large volumes are required for bowel preparation, nausea and vomiting can be induced and sometimes lead to the discontinuation of bowel preparation. To improve tolerability, low-volume (2 L) PEG plus adjuvants or other laxatives, such as magnesium citrate with sodium picosulfate, have been introduced. Multiple studies have demonstrated that low-volume PEG plus adjuvants or other laxatives is associated with less nausea and vomiting[10-12]. Nevertheless, adjuvants and other laxatives are not appropriate for patients with severe renal insufficiency, especially when the creatinine clearance is < 30 mL/min. High-volume PEG is recommended for bowel preparation in patients with renal failure[1,2].

Perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract is life-threatening. Esophageal perforations have an incidence of 3.1/1000000 per year[13], making them relatively more common than the exceedingly rare pharyngeal perforations, which are primarily due to iatrogenic injuries or foreign bodies[14-16]. Spontaneous pharyngeal perforation secondary to vomiting or retching is extremely rare. Roh et al[17]. Reported a case of pharyngeal perforation induced by forceful vomiting in 2008. Furthermore, Zenga et al[16]. published a single-center, retrospective study of 28 patients with hypopharyngeal or cervical esophageal perforations in 2015, in which only one case was attributed to retching. To date, pharyngeal perforation during bowel preparation for colonoscopy has not been reported.

Although the management of esophageal perforations has been well described, no definitive guidelines for the management of pharyngeal perforations have been established owing to their rarity, and treatment remains controversial[14]. A multidisciplinary approach is crucial for optimizing outcomes in the treatment of pharyngeal perforations[14-16]; in our case, multidisciplinary team consisting of gastroenterologists, thoracic surgeons, and otolaryngologists, participated in the management of pharyngeal perforation. The choice between surgery and conservative management depends on the perforation etiology, size and location, time to treatment, complications, and the patient’s overall condition. Conservative management is preferred under the following conditions: mild symptoms, small perforation size (< 0.5–1 cm), absence of pleural or mediastinal complications, no contrast medium leakage on computed tomography, and iatrogenic trauma origins[14,16,18]. Our patient underwent conservative medical management because of mild symptoms, stable vital signs, and a small lesion size. One of the most important prognostic factors is early recognition. Early treatment within 24-36 h after perforation is associated with a favorable prognosis[15], and early diagnosis within 24 h from injury to diagnosis presents significantly better outcomes in conservative management[16]. In our case, chest radiography and computed tomography were performed within several hours of appearance of the patient’s symptoms, leading to prompt management and a favorable outcome.

In summary, despite its rarity, pharyngeal perforation should be considered a potential complication during bowel preparation for colonoscopy in cases of sudden pain in the neck, throat, and anterior chest following forceful vomiting. This case highlights the importance of early recognition and prompt management of pharyngeal perforation induced by forceful vomiting during bowel preparation.

| 1. | Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, Spada C, Benamouzig R, Bisschops R, Bretthauer M, Dekker E, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ferlitsch M, Fuccio L, Awadie H, Gralnek I, Jover R, Kaminski MF, Pellisé M, Triantafyllou K, Vanella G, Mangas-Sanjuan C, Frazzoni L, Van Hooft JE, Dumonceau JM. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51:775-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Saltzman JR, Cash BD, Pasha SF, Early DS, Muthusamy VR, Khashab MA, Chathadi KV, Fanelli RD, Chandrasekhara V, Lightdale JR, Fonkalsrud L, Shergill AK, Hwang JH, Decker GA, Jue TL, Sharaf R, Fisher DA, Evans JA, Foley K, Shaukat A, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Wang A, Acosta RD. Bowel preparation before colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:781-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Latos W, Aebisher D, Latos M, Krupka-Olek M, Dynarowicz K, Chodurek E, Cieślar G, Kawczyk-Krupka A. Colonoscopy: Preparation and Potential Complications. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Santoro MJ, Chen YK, Collen MJ. Polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution-induced Mallory-Weiss tears. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1292-1293. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yu JY, Kim SK, Jang EC, Yeom JO, Kim SY, Cho YS. Boerhaave's syndrome during bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol in a patient with postpolypectomy bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:270-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Emmanouilidis N, Jäger MD, Winkler M, Klempnauer J. Boerhaave syndrome as a complication of colonoscopy preparation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011;5:544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rastogi A, Wani S. Colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Fisher DA, Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Jain R, Jue TL, Khan KM, Malpas PM, Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Dominitz JA. Complications of colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:745-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim SY, Kim HS, Park HJ. Adverse events related to colonoscopy: Global trends and future challenges. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:190-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 10. | Clark RE, Godfrey JD, Choudhary A, Ashraf I, Matteson ML, Bechtold ML. Low-volume polyethylene glycol and bisacodyl for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:319-324. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Xie Q, Chen L, Zhao F, Zhou X, Huang P, Zhang L, Zhou D, Wei J, Wang W, Zheng S. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid versus standard-volume polyethylene glycol solution as bowel preparations for colonoscopy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cheng J, Tao K, Shuai X, Gao J. Sodium phosphate versus polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy bowel preparation: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4033-4041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vidarsdottir H, Blondal S, Alfredsson H, Geirsson A, Gudbjartsson T. Oesophageal perforations in Iceland: a whole population study on incidence, aetiology and surgical outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:476-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bourhis T, Mortuaire G, Rysman B, Chevalier D, Mouawad F. Assessment and treatment of hypopharyngeal and cervical esophagus injury: Literature review. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137:489-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hinojar AG, Díaz Díaz MA, Pun YW, Hinojar AA. Management of hypopharyngeal and cervical oesophageal perforations. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:175-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zenga J, Kreisel D, Kushnir VM, Rich JT. Management of cervical esophageal and hypopharyngeal perforations. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36:678-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Roh JL, Park CI. Spontaneous Pharyngeal Perforation After Forceful Vomiting: The Difference from Classic Boerhaave's Syndrome. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;1:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Onat S, Ulku R, Cigdem KM, Avci A, Ozcelik C. Factors affecting the outcome of surgically treated non-iatrogenic traumatic cervical esophageal perforation: 28 years experience at a single center. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |