Published online Jun 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3603

Revised: April 22, 2024

Accepted: May 15, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2024

Processing time: 102 Days and 23.6 Hours

Due to the specificity of Chinese food types, gastric phytobezoars are relatively common in China. Most gastric phytobezoars can be removed by chemical enzyme lysis and endoscopic fragmentation, but the treatment for large phyto

For giant gastric phytobezoars that cannot be dissolved and fragmented by conventional treatment, we have invented a new lithotripsy technique (tennis ball cord combined with endoscopy) for these phytobezoars. This non-interventional treatment was successful in a patient whose abdominal pain was immediately relieved, and the gastroscope-induced ulcer healed well 3 d after lithotripsy. The patient was followed-up for 8 wk postoperatively and showed no discomfort such as abdominal pain.

The combination of tennis ball cord and endoscopy for the treatment of giant gastric phytobezoars is feasible and showed high safety and effectiveness, and can be widely applied in hospitals of all sizes.

Core Tip: Due to the specificity of Chinese food types, gastric phytobezoars are relatively common in China. Most gastric phytobezoars can be removed by chemical enzyme lysis and endoscopic fragmentation, but the treatment for large phytobezoars is limited. We developed a new, safe, and inexpensive lithotripsy procedure for this condition using tennis ball cord combined with endoscopy. This new technique reduces the dependence on endoscopic instruments, may be more widely applied in hospitals of all sizes.

- Citation: Shu J, Zhang H. Tennis ball cord combined with endoscopy for giant gastric phytobezoar: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(18): 3603-3608

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i18/3603.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3603

In China, phytobezoars are the most common occurrence in Gastric bezoars[1], Gastric phytobezoars are usually an aggregation of indigestible substances in the stomach, most often caused by eating persimmons, pineapples, prunes, celery, coconut fiber or hawthorn-like foods on an empty stomach[2]. Treatment options include chemical enzyme lysis, endoscopic fragmentation, laser lithotripsy techniques, and surgical excision[3-7]. Surgical procedures are often required for huge gastric phytobezoars that cannot be dissolved and fragmented by conventional treatment. However, as surgical procedures have many disadvantages, we invented a new, safe, and inexpensive lithotripsy procedure for this condition using tennis ball cord combined with endoscopy.

A 55 year old female patient visited our department due to epigastric pain after consuming persimmons on an empty stomach two weeks previously.

The patient presented with recurrent epigastric pain after consuming persimmons on an empty stomach two weeks previously, without obvious regularity. She denied eating too much or stimulating food. She presented with upper abdominal pain. There was no acid reflux, nausea, vomiting, fullness or black stools. Both stool and urine samples were normal.

The patient had always been in good health. Occasionally, abdominal pain, distension and other discomfort occurred due to overeating, but the discomfort symptoms were relieved following reduced food intake. The results of gastroscopy examination were basically normal one year ago.

She had no underlying diseases, no alcohol or smoking habits, and her teeth were intact. She denied any surgical history, and was not taking any medication. She denied the history of hypertension, diabetes, coronary heart disease, gastric surgery, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, and drug and food allergy; there was no family history of digestive disease.

During the physical examination, her temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate were normal. An abdominal examination showed light pressure pain in the epigastrium. No other physical abnormalities were noted.

She was not anemic and had a negative fecal occult blood test. Fasting blood glucose, thyroid function, parathyroid function, electrolytes and calcium were all normal. The results of other laboratory tests were unremarkable.

Abdominal computed tomography showed that the stomach was filled with fluid and some food.

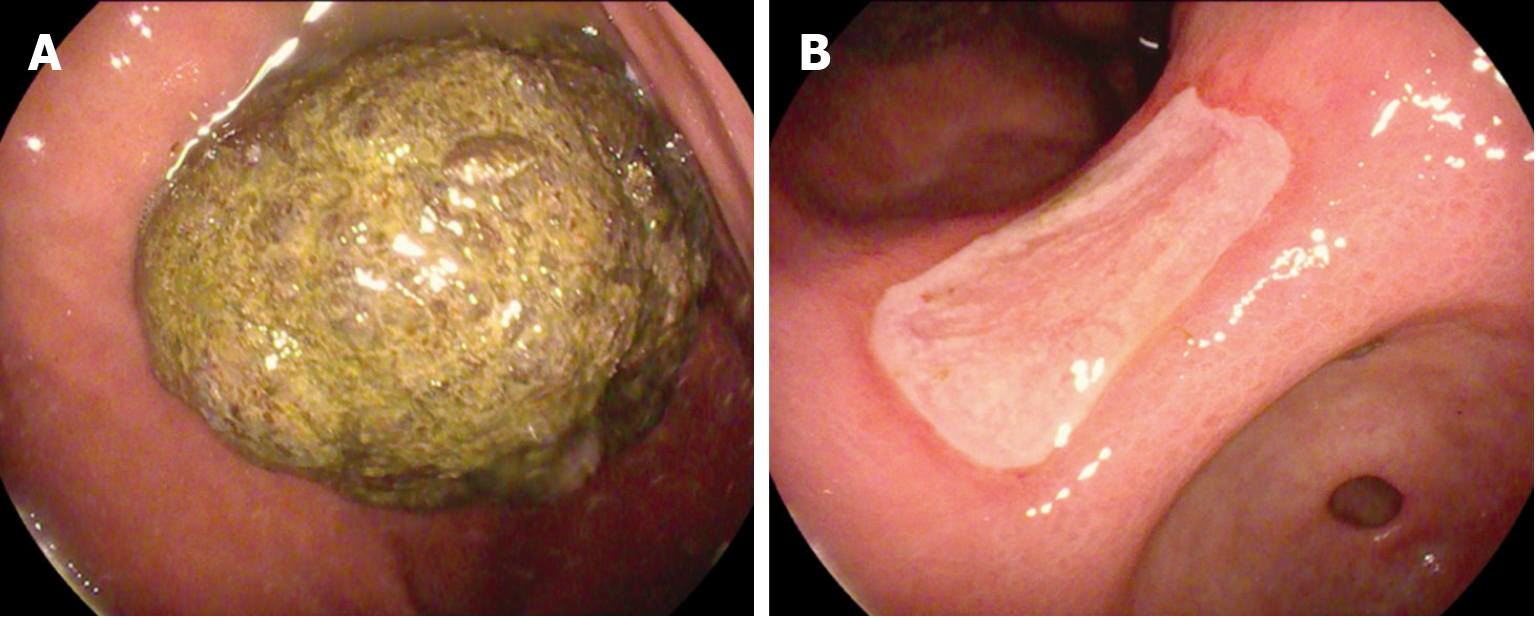

On the second day of admission, gastroscopy was performed, which revealed a long oval-shaped gastric phytobezoar approximately 50 mm × 50 mm × 60 mm in size and a shallow ulcer about 10 mm × 20 mm in the corner of the stomach (Figure 1). Pathology confirmed that the ulcer was benign. In order to alleviate the patient's abdominal pain and promote healing of the gastric ulcer, esomeprazole enteric tablets (20 mg po qd) was administered. Due to the size of her gastric phytobezoar and the high failure rate of endoscopic lithotripsy, the patient received chemical therapy first, and we informed the patient that if this treatment failed, endoscopic fragmentation would be performed, and with time, the success rate of non-interventional treatment may be reduced before the patient could make a decision. The patient was instructed to consume cola (about 500-1000 mL) and pancreatic enzyme (300 mg po tid) daily. During treatment, the patient experienced no significant relief of abdominal pain and still had persistent vague subxiphoid pain. Gastroscopy was repeated on the fifth day after admission and revealed a gastric phytobezoar essentially the same size as before and no significant change in the size of the gastric ulcer.

The diagnosis of abdominal pain caused by a giant gastric phytobezoar was made.

Lithotripsy procedure using tennis ball cord combined with endoscopy was performed.

The patient and her family members were informed that this was a new technique which had not been tried before, and endoscopic lithotripsy failure could occur during the operation. All agreed to try endoscopic lithotripsy.

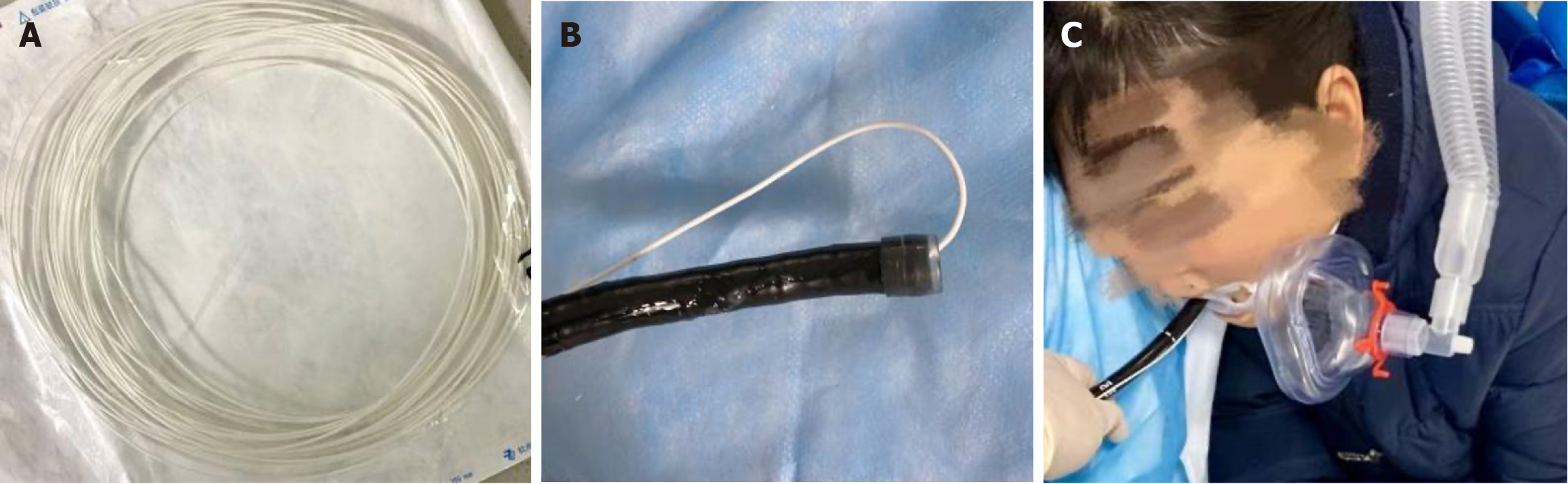

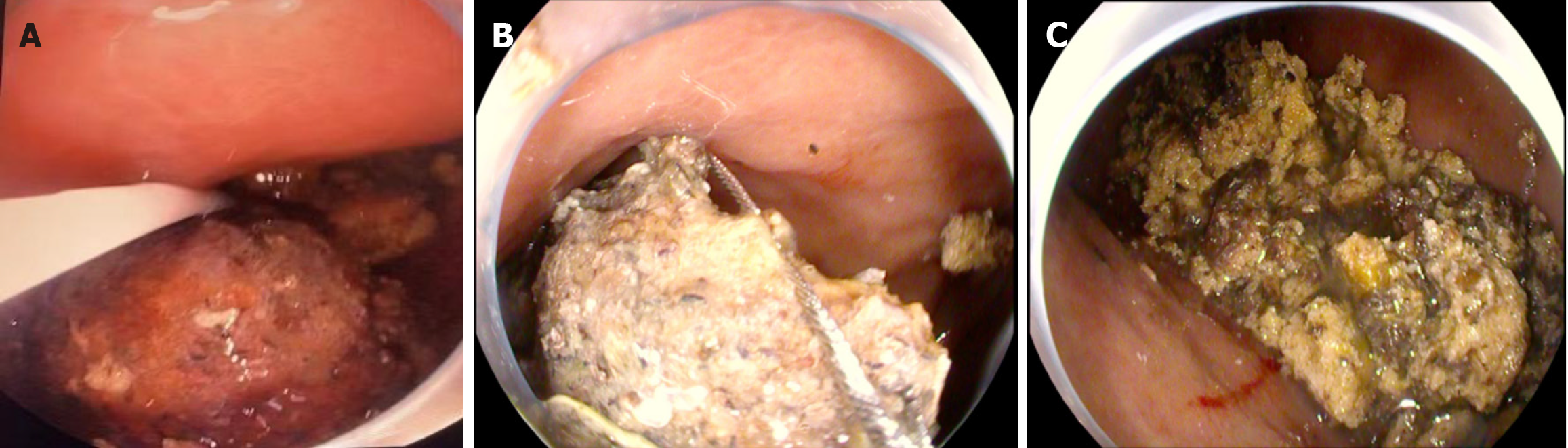

The patient was placed under intravenous anesthesia, and a gastroscope with a clear cap was inserted into the gastric cavity, first with a foreign body clamp to create a shallow groove in the middle of the long diameter of the gastric phytobezoar. The gastroscope was withdrawn, and then one end of the prepared sterile tennis ball cord was inserted into the gastroscope clamp tract, the cord was reflexed and fixed with the mirror body after passing through the clamp tract and the transparent cap for about 140 cm. This formed a coil with some toughness, and the endoscopic operator adjusted the size of the coil by controlling the tennis ball cord at the end of the endoscope clamp tract (Figure 2). We re-inserted the gastroscope with the tennis ball cord into the patient’s gastric cavity, while the assistant fixed the outside of the mirror body, the operator adjusted the size of the coil in the stomach according to the diameter of the gastric phytobezoar and fixed the coil firmly in the shallow groove that was clamped. The endoscope operator tightened the tennis ball cord at the jaw end and pulled the cord repeatedly with force. When the phytobezoar was < 2.0 cm in diameter after repeated fragmentation, the largest fragment was strangled with the help of a snare (Figure 3).

When the patient was awake, we instructed her to drink a large amount of excretory medication (e.g., pre-colonoscopy excretory medication polyethylene glycol electrolyte dispersion) and to take pro-intestinal motility medication to quickly expel the tiny gastric phytobezoars that had been fragmented in the stomach to prevent intestinal obstruction.

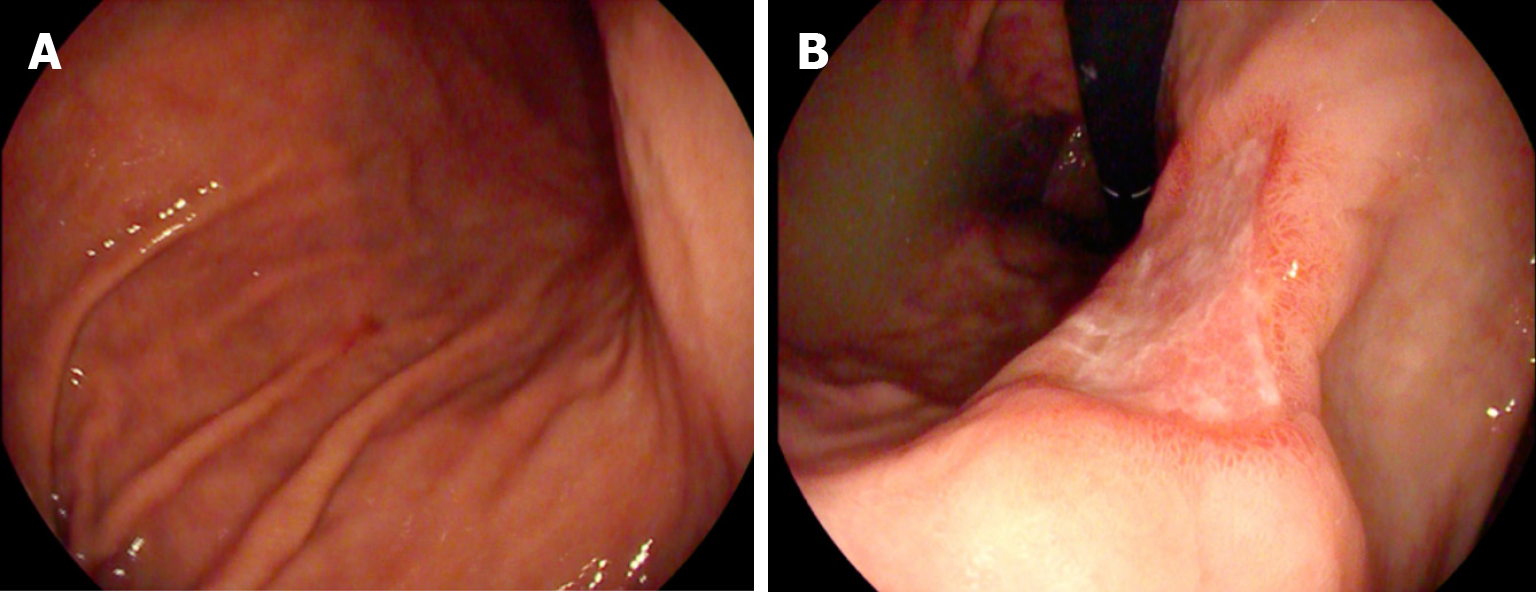

Gastroscopy was repeated three days later, and all the phytobezoars in the patient’s stomach had been expelled (Figure 4), and the patient did not have any abdominal discomfort or related complications. No recurrence of abdominal pain was observed during the 8-wk follow-up period.

Bezoars are aggregates of indigestible substances that accumulate in the gastrointestinal tract. Can be classified according to their composition; phytobezoar, pharmacobezoar, lactobezoar, trichobezoar, and bezoars containing paper towels or polystyrene foam. In China, hawthorn and persimmon are the most common causes of plant bezoars[8]. Persimmon belongs to the tree plant, is widely distributed fruit tree in China[9], it is loved by the Chinese. Hawthorn is similar to persimmon and contains rich tannins. After gastric digestion, the agglutination between tannins and dietary proteins occurs, forming the phytobezoars[10]. They occur most frequently in patients with risk factors, i. e., previous gastric surgery, endocrine, neuropsychiatric disorders, or other diseases leading to abnormal gastric function, or gastric dysperistalsis[11]. Bezoars may be asymptomatic, but most commonly cause abdominal discomfort or pain, vomiting, nausea, and a feeling of fullness, small intestine obstruction, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding[11,12].

In our study, the phytobezoar formed after the patient had eaten persimmon on an empty stomach, and the gastric mucosa formed a gastric ulcer due to repeated friction by the gastric phytobezoar and caused abdominal pain and other discomfort. Due to the large size of the phytobezoar, the snare could not be crushed. We found that tennis ball cord combined with endoscopic lithotripsy can be used as a remedy for giant gastric phytobezoars, which could not be lysed by chemical enzymes and cannot be fragmented by conventional endoscopic instruments (e.g., trap, lithotripsy mesh basket, etc.). Tennis ball cord is inexpensive and easily accessible, and combined with endoscopic lithotripsy is less invasive and less expensive than laser lithotripsy and surgical procedures. This can greatly reduce the financial burden on patients and therefore enjoys a high degree of acceptance. The lithotripsy technique has low dependence on endoscopic instruments and can be carried out in both large and primary hospitals. Another advantage is that the tennis ball cord can be adjusted to the size of the coil according to the diameter of the phytobezoar, and is not limited by the phytobezoar’s diameter. In addition, due to the high strength of the cord, there is no risk of the procedure being prolonged due to intraoperative coil breakage. We placed a transparent cap on the lens before the operation to maintain the clarity of the field of view during the operation and to protect the lens from being damaged by the gastric phytobezoar during lithotripsy. Following lithotripsy, the patient was instructed to drink a lot of excretory medication and to take regular pro-intestinal motility medication to quickly expel the small phytobezoars from her body and avoid intestinal obstruction. The patient was also instructed to take cola orally for two more days to help dissolve the small phytobezoars that had not yet been excreted. After lithotripsy, the patient was observed for abdominal pain, other discomfort, and for early detection of new intestinal obstruction.

The combination of tennis ball cord and endoscopy for the treatment of giant gastric phytobezoars is feasible. Furthermore, this technique shows high safety and effectiveness. This technique can reduce intraoperative pain, decrease procedural risk, reduce the patient’s financial burden, and reduce the dependence on endoscopic instruments, and can be widely applied in hospitals of all sizes.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Baishideng Publishing Group Inc. for publishing this report.

| 1. | Ben-Porat T, Sherf Dagan S, Goldenshluger A, Yuval JB, Elazary R. Gastrointestinal phytobezoar following bariatric surgery: Systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1747-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Moffat JH, Fraser WP. Gastric Bezoar. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;87:813-814. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Iwamuro M, Tanaka S, Shiode J, Imagawa A, Mizuno M, Fujiki S, Toyokawa T, Okamoto Y, Murata T, Kawai Y, Tanioka D, Okada H, Yamamoto K. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of nineteen Japanese patients with gastrointestinal bezoars. Intern Med. 2014;53:1099-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kurt M, Posul E, Yilmaz B, Korkmaz U. Endoscopic removal of gastric bezoars: an easy technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:895-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kuo JY, Mo LR, Tsai CC, Chou CY, Lin RC, Chang KK. Nonoperative treatment of gastric bezoars using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:386-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grande G, Manno M, Zulli C, Barbera C, Mangiafico S, Alberghina N, Conigliaro RL. An alternative endoscopic treatment for massive gastric bezoars: Ho:YAG laser fragmentation. Endoscopy. 2016;48 Suppl 1:E217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ulukent SC, Ozgun YM, Şahbaz NA. A modified technique for the laparoscopic management of large gastric bezoars. Saudi Med J. 2016;37:1022-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chun J, Pochapin M. Gastric Diospyrobezoar Dissolution with Ingestion of Diet Soda and Cellulase Enzyme Supplement. ACG Case Rep J. 2017;4:e90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao Y, Su K, Wang G, Zhang L, Zhang J, Li J, Guo Y. High-Density Genetic Linkage Map Construction and Quantitative Trait Locus Mapping for Hawthorn (Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge). Sci Rep. 2017;7:5492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang RL, Yang ZL, Fan BG. Huge gastric disopyrobezoar: a case report and review of literatures. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khan S, Khan IA, Ullah K, Khan S, Wang X, Zhu LP, Rehman MU, Chen X, Wang BM. Etiological aspects of intragastric bezoars and its associations to the gastric function implications: A case report and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lin L, Wang C, Wu J, Liu K, Liu H, Wei N, Lin W, Jiang G, Tai W, Su H. Gastric phytobezoars: the therapeutic experience of 63 patients in Northern China. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112:12-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |