Published online Jun 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3567

Revised: April 13, 2024

Accepted: May 6, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2024

Processing time: 111 Days and 6.9 Hours

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) injuries rarely occur during blunt abdominal injuries, with an incidence of < 1%. The clinical manifestations mainly include abdominal hemorrhage and peritoneal irritation, which progress rapidly and are easily misdiagnosed. Quick and accurate diagnosis and timely effective treatment are greatly significant in managing emergent cases. This report describes emer

A 55-year-old man with hemorrhagic shock presented with SMA rupture. On admission, he showed extremely unstable vital signs and was unconscious with a laceration on his head, heart rate of 143 beats/min, shallow and fast breathing (frequency > 35 beats/min), and blood pressure as low as 20/10 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa). Computed tomography revealed abdominal and pelvic hematocele effusion, suggesting active bleeding. The patient was suspected of partial rupture of the distal SMA branch. The patient underwent emergency mesenteric artery ligation, scalp suture, and liver laceration closure. In view of conditions with acute onset, rapid progression, and high bleeding volume, key points of nursing were conducted, including activating emergency protocol, opening of the green channel, and arranging relevant examinations with various medical staff for quick diagnosis. The seamless collaboration of the multidisciplinary team helped shorten the preoperative preparation time. Emergency laparotomy exploration and mesenteric artery ligation were performed to mitigate hemorrhagic shock while establishing efficient venous accesses and closely monitoring the patient’s condition to ensure hemodynamic stability. Strict measures were taken to avoid intraoperative hypothermia and infection.

After 3.5 h of emergency rescue and medical care, bleeding was successfully controlled, and the patient’s condition was stabilized. Subsequently, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for continuous monitoring and treatment. On the sixth day, the patient was weaned off the ventilator, extubated, and relocated to a specialized ward. Through diligent medical intervention and attentive nursing, the patient made a full recovery and was discharged on day 22. The follow-up visit confirmed the patient’s successful recovery.

Core Tip: Case report of a 55-year-old male man with extremely unstable vital signs and was unconscious with a laceration on his head, a heart rate of 143 beats/min, shallow and fast breathing caused by trauma, diagnosed with superior mesenteric artery rupture, abdominal hemorrhage, hemorrhagic shock, and scalp laceration. After admission, he was successfully rescued by multidisciplinary team.

- Citation: Lin XP, Guo XL, Tian HF, Wu ZR, Yang WJ, Pan HY. Emergency rescue of a patient with hemorrhagic shock caused by superior mesenteric artery rupture: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(18): 3567-3574

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i18/3567.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3567

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is a visceral branch of the abdominal aorta that provides blood and nutrition to the intestinal segment through various branches[1]. SMA injuries rarely result from blunt abdominal injuries, with an incidence < 1%. The clinical manifestations mainly include abdominal hemorrhage and peritoneal irritation, which progress rapidly and are easily misdiagnosed. The severity of SMA injuries is crucially related to the bleeding rate and volume. For example, massive bleeding in a short time can be fatal with a mortality rate as high as 25%–68%[2,3]. Quickly and accurately identifying the disease and timely administering effective treatment significant impact the emergency rescue of patients but create challenges in clinical nursing[4]. In this report, a patient in critical condition presenting with hemorrhagic shock caused by SMA rupture was admitted to a grade III-A general hospital in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, on June 28, 2023. After the emergency rescue, the bleeding was controlled, and the patient was stabilized. After careful nursing, the patient was eventually smoothly discharged. The nursing experience is described subsequently.

The patient, a 55-year-old man, suffered multiple injuries for approximately 1 h after his vehicle crashed into a wall. He was rushed to our hospital for emergency treatment by an ambulance after 120 first-aid calls.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

The patient had a free previous medical history.

On admission, he showed extremely unstable vital signs and was unconscious with a laceration on his head, a heart rate of 143 beats/min, shallow and fast breathing (frequency > 35 beats/min), and blood pressure as low as 20/10 mmHg (1 mmHg = 0.133 kPa). The patient was diagnosed with abdominal hemorrhage, hemorrhagic shock, and scalp laceration.

Whole blood glucose 28.21 mmol/L, pH-corrected 6.855, base excess at -24.0 mmol/L, whole blood-lactamase > 20.0000 mmol/L; alanine aminotransferase at 62 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase at 168 U/L, glutamyltransferase at 128 U/L.

Emergency bedside ultrasound showed left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular hypocontractility, mild tricuspid and mitral regurgitation. Emergency computed tomography (CT) showed slightly swollen soft tissue pneumatization on the right frontal parietal, and emergency cranial CT intracranial did not show any obvious signs of urgency; review as necessary.

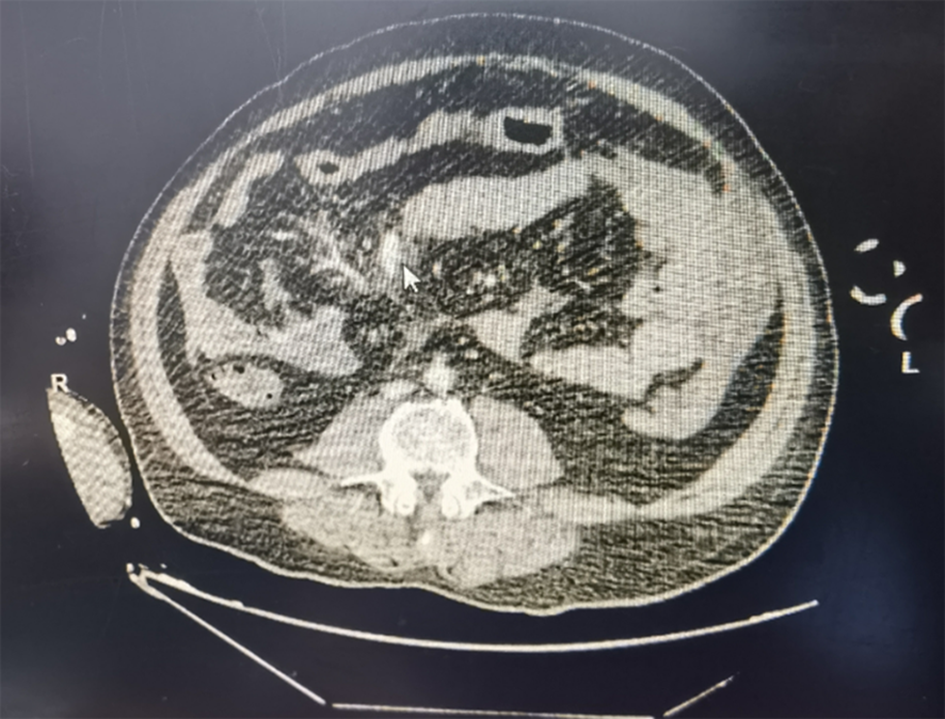

CT showed abdominal and pelvic hematocele effusion, suggesting active bleeding. The patient was suspected of partial rupture of the distal SMA branch (Figure 1).

SMA rupture, hemorrhagic shock, hepatic contusion, mesenteric hemorrhage, hepatic hemorrhage.

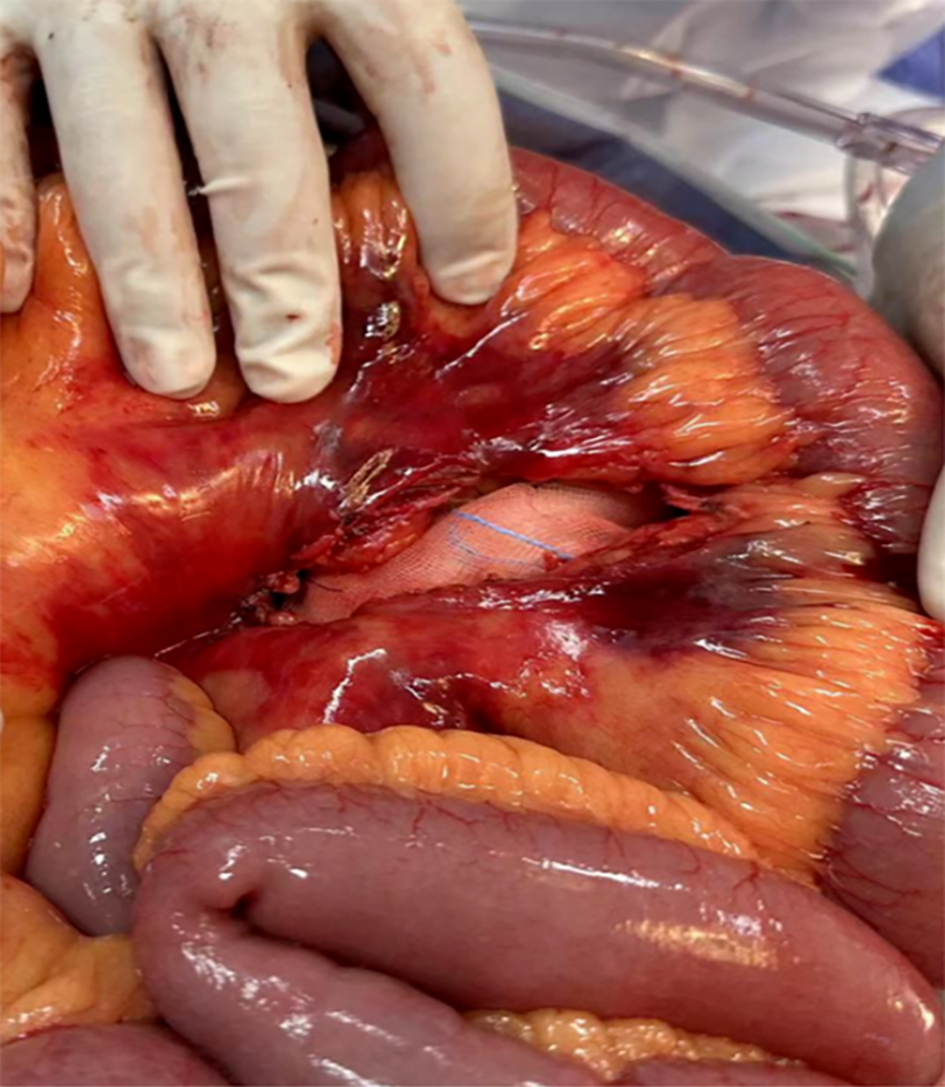

Immediately after admission, the patient was hooked to a tracheal intubation ventilator for assisted breathing and given norepinephrine to maintain hemodynamic stability, tranexamic acid to stop hemostasis, fluid replacement, blood transfusion, and other antishock therapy. Because the patient was in a coma, and his family members were unreachable, the case was reported to the general duty officer and medical department of the hospital, and corresponding signatures were acquired for emergency rescue. After contraindications were ruled out, the patient underwent emergency mesenteric artery ligation, scalp suture, and liver laceration closure. Abdominal exploration revealed massive bleeding and blood clots (approximately 3000-4000 mL), a longitudinal 25-cm tear in the middle part of the small intestine accompanied by significant active bleeding, and a partial tear of the liver capsule with bleeding (Figure 2). During the operation, 1.5 units red blood cell suspension and 840 mL fresh-frozen plasma were infused, and 1500 mL autologous blood was recovered. The operation lasted 3.5 h and was uneventful, with bleeding controlled from the root cause. After surgery, the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for further monitoring and treatment. The ventilator was removed on day 6, and the patient was transferred to a specialized ward.

After active treatment and careful nursing, the patient recovered sufficiently and was discharged on day 22. The patient’s successful recovery was confirmed on follow-up.

The patient was rushed to the emergency room for treatment by an ambulance after 120 first-aid calls. On admission, the patient was unconscious and restless and presented with wet and cold skin with cyanosis. The nurse initiated electrocardiogram monitoring with full understanding of the pathogenesis and inducement and quickly recorded the patient’s vital signs: Heart rate of 143 beats/min, shallow and fast breathing with frequency > 35 beats/min, blood pressure of 40/20 mmHg, and shock index (pulse rate/systolic blood pressure) > 2 that indicated severe shock[4,5]. The case was immediately reported to administrative general duty officer, and the emergency process was initiated, with saving the life of the patient as the first principle. The nursing staff assisted the doctors in establishing an advanced airway by tracheal intubation and ventilator for assisted ventilation and to immediately open two venous accesses in the left femoral and radial veins for 18 G venous indwelling needles. Two venous blood specimens were drawn for cross-matching, and arterial blood was collected for arterial blood gas analysis. An urgent application was made to the blood transfusion department for red blood cells and plasma. In addition, according to the doctor’s advice, normal saline and hydroxyethyl starch were quickly infused into the patient for volume expansion and fluid replacement. The nurse staff also urgently contacted and cooperated with other doctors for CT assessment of the abdominal and pelvic hematocele effusion. The CT results suggested active bleeding, which raised the suspicion of partial rupture of the distal SMA branch. The blood pressure further decreased to 20/10 mmHg, whole blood glucose was 28.21 mmol/L, and whole blood lactic acid was > 20 mmol/L, indicating severely insufficient tissue perfusion. The patient was diagnosed with abdominal active bleeding caused by mesenteric artery injury. The team evaluated the risk of bleeding and ischemia and endorsed the patient to the operating room for urgent abdominal exploration to stop the bleeding at the bleeding site and for follow-up therapy.

Seamless collaboration of a multidisciplinary team: During the treatment of this case, the emergency process was immediately initiated after patient admission. One nurse assisted in tracheal intubation, recorded the patient‘s vital signs in real time, and quickly completed the relevant preoperative preparations, such as skin preparation and indwelling catheter insertion. One nurse opened vascular access, administered drugs for rehydration and blood transfusion, and promptly recorded and reported the changes in the patient’s condition. Another nurse collected blood for examination, facilitated bedside electrocardiography, cardiac color ultrasound, and pelvic and abdominal cavity CT and followed up the results. Another nurse facilitated overall arrangements and external liaisons and ensured that logistics and related departments quickly distributed the drugs and materials needed for the emergency treatment. The chief duty officer rushed to the scene within 5 min and initiated the opening of the green channel. The Department of General Surgery conducted an emergency consultation to determine the treatment plan and advised the operating room to prepare for the operation. After receiving the emergency operation notice, the operating room immediately notified the head anesthesiologist and head nurse, enlisted the cooperation of nurses with strong professional skills and rescue experience, coordinated with other relevant personnel, and prepared the operating room[6]. The anesthesiology department performed emergency bedside endotracheal intubation in the emergency room to provide respiratory support and assisted the transfer team in escorting the patient to the operating room. Surgeons and itinerant nurses held the door of the operating room for quick convergence and minimization of risk[7]. In this case, the nurses had a basic judgment of the patient’s condition, and the tacit cooperation of the team salvaged valuable time for the operation and ensured efficiency in medical care.

Efficient preoperative preparation: Efforts were made to fully anticipate all kinds of possible extraordinary accidents to enable efficient preparation in the shortest possible time, ensure intraoperative nursing safety, and improve rescue efficiency[8]. In this case, the following measures enabled efficient preoperative preparation: (1) Changes in the patient’s condition were closely monitored. Based on the early identification of hemorrhagic shock, the doctor made various preoperative preparations for the patient while conducting consultation, which shortened the idle time; (2) the patient was in severe posttraumatic shock. CT indicated showed mesenteric artery injury, and the diagnosis was clear. Therefore, the patient was quickly transferred to the operating room through the emergency green channel, and the emergency plan for treating massive hemorrhage was initiated. The team worked together to locate and stop the bleeding while waiting for the test results. Admission to transfer to the operating room took 23 min, which signified efficiency in administering emergency care; and (3) after receiving the notice, the operating room coordinated with the relevant backup personnel to assist in the preparation of emergency surgical equipment to ensure that the operating room was fully equipped in a normal standby state with normal functions. In addition, backup personnel prepared surgical consumables and instruments, including high-value medical consumables, such as vascular sutures and hemostatic materials of various models. The staff also prepared conventional consumables, such as cloth instruments, electrotome, gloves, and other accessories; checked if they were within the validity period; assisted in preparing the sterile table; and let the scrub nurse directly sort out the table after handwashing. The operating room was sufficiently prepared within 8 min, including the instrument inspection and inventory by the scrub nurse before the patient was transferred, and the staff cooperated fully during the surgery, which improved the quality of the rescue operation.

Establishment of effective venous accesses: In antishock therapy, three or more venous accesses need to be opened to maintain circulation and guarantee subsequent blood transfusion and rescue medication[9,10]. The rounding nurse assisted the anesthesiologists in placing a catheter in the right subclavian jugular vein of the patient to monitor the central venous pressure and maintain the anesthesia and low-dose norepinephrine micropump during the operation, as well as to prevent the drug from stimulating the peripheral vein and promptly infuse a large amount of fluid and blood components during the operation. The support personnel initiated indwelling needle puncture in the thick and straight veins in the forearm of the right hand while avoiding the radial artery of the wrist. Furthermore, they reserved a site for anesthesia artery puncture to monitor invasive blood pressure and prepare for emergency blood transfusion. These measures enabled quick and effective administration of emergency blood collection, pressurized blood transfusion, rapid fluid replacement, blood volume supplement, and relief of other symptoms of shock. The indwelling intravenous catheter inserted before the operation was used for anesthesia, intraoperative infusion, and drugs.

Close monitoring of the disease changes: Trauma is a time-limited condition, and administering medical care within the time window is the core of severe trauma treatment[11]. Invasive arterial blood pressure was established preoperatively to effectively monitor hemodynamic changes. Blood was collected for arterial blood gas analysis[12]. Decreased blood pressure is a sensitive indicator of shock, while blood lactic acid is a sensitive indicator of tissue perfusion insufficiency. Critically ill patients often have hyperlactic acidemia with a concentration ≥ 2.0 mmol[13,14]. The patient was in the compensatory stage of hemorrhagic shock, and his condition was critical. Successive blood gas analyses indicated decompensated respiratory acidosis and respiratory failure. On admission, the patient’s whole blood lactic acid was 20 mmol/L (reference interval: 0.90–1.70 mmol/L). A nurse dynamically monitored the parameters of the patient’s reactive capacity, such as invasive arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and central venous pressure in real time; changes in levels of whole blood lactic acid, hemoglobin, arterial oxygen partial pressure, carbon dioxide partial pressure, blood oxygen saturation, blood pH, electrolytes, and blood coagulation function for evaluation of the tissue perfusion; and recorded the urine color, volume, and in–out volume. The cardiology, digestive medicine, and neurosurgery departments worked together in consultation to evaluate the patient’s condition. The blood transfusion and anesthesia departments and the intensive care unit worked together to discuss treatment plans, formulate emergency plans for bleeding, and adjust the amount and speed of rehydration in time according to the monitored blood volume.

Maintenance of hemodynamic stability: Maintaining hemodynamic stability is an important but challenging task in intraoperative nursing[15]. Clinical outcomes can be improved by minimizing blood loss to reduce/avoid allogeneic blood transfusion, regulating blood coagulation, and preventing and treating anemia[16]. The first symptom of this patient was abdominal hemorrhage and hemorrhagic shock caused by acute trauma. In the course of disease deve

Strict prevention of intraoperative hypothermia: Hypothermia can result in decreased immunity, increased incidence of chills and risk of infection, and trigger arrhythmias and myocardial ischemia, as well as blood coagulation and metabolic disorders[9]. Because of various factors, such as rapid fluid replacement, anesthetic drug administration, body cavity exposure, and intraoperative irrigation, a risk of hypothermia arises during operation; thus, comprehensive management of the patient’s body temperature is important[20]. The following warm-keeping measures were performed in the current case: the operating room was set to heating mode, and the temperature was raised to 28 °C. The lower body of the patient was covered with an inflatable heating blanket, and a heater was used for warmth. The neck and shoulders of the patient were covered with a blanket to reduce skin exposure. An infusion heating instrument was used to maintain the infusion at 37 °C, and the body cavity and incision were rinsed with 42 °C water intraoperatively. The body temperature was monitored constantly and recorded. Because of the persistence of objective factors, such as excessive bleeding and body cavity exposure, after the application of warm-keeping measures, the body temperature of the patient did not return to more than 36° C, but also did not decrease continuously. Instead, it fluctuated between 34.6 °C and 35.5 °C. After the bleeding was controlled, and the body cavity was closed, the body temperature gradually returned to 35.9 °C.

Active prevention of infection: A green channel for emergency rescue in the operating room was opened for the patient. The rescue involved many relevant medical personnel. Intraoperative body cavity exposure, arteriovenous puncture, and other invasive pipelines can significantly increase the risk of postoperative infection[6,21]. To reduce the risk of surgical infection, the multidisciplinary team made a joint diagnosis and treatment of the patient to actively prevent infection, mitigate shock, and improve cardiopulmonary function. The following nursing measures were taken: (1) The multidisciplinary team collaborated seamlessly to effectively shorten the preoperative preparation time and reduce frequency of access by intraoperative personnel to the operating room; (2) an aseptic operation was strictly conducted. Hand hygiene was observed, and surgical instruments used intraoperatively were washed according to specifications. Items used intraoperatively were recovered promptly to reduce the pollution of instrument sources; (3) changes in the patient’s condition were continuously monitored to prevent occult infection. Items such as transfer bed, micropump, and monitor transferred to the operating room with the patient were wiped and disinfected with medical disinfectant wipes; and (4) changes in the patient’s body temperature, blood culture, and sputum culture results were monitored. Perioperative antibiotics were adopted rationally according to the doctor’s advice, with a one-time dose of 4.5 g piperacillin and tazobactam administered to the patient via intravenous drip for 8 h to prevent infection. The patient did not experience postoperative malaise, such as fever. On the second day postoperatively, the patient had a white blood cell count of 9.5 × 109/L, neutrophil percentage of 76.4%, and procalcitonin of 4.34 ng/mL.

The patient was diagnosed with hemorrhagic shock due to SMA rupture following a vehicular accident. With saving the life of the patient as the first principle, the multidisciplinary team mobilized the emergency plan and opened the green channel in time. The team made the correct evaluation in the shortest time, expanded the volume and in time, and successfully performed rescue medical care. The team effectively shortened the preoperative preparation time through seamless convergence and efficient and rapid emergency response and provided high-quality professional nursing care for successful treatment. The operating room team contributed significantly to the successful treatment through the following measures: Strengthening the entire perioperative management process; establishing effective venous access; closely monitoring the changes of the patient’s condition; performing preventive measures and establishing various emergency plans to stabilize hemodynamics; and providing high-quality, meticulous care for the patient.

These measures ensured the smooth administration of emergency care that successfully saved the patient’s life and ensured his rehabilitation. This case was critical with a narrow time limit. The patient was in shock on admission, which was potentially fatal. The medical staff made a correct assessment in the shortest possible time and promptly administered warm and pressurized blood transfusion to expand the blood volume. In addition, other crucial measures, such as mastering clinical rescue skills, effective cooperation, and payment of medical expenses after rescue were performed. This report showed that the above measures effectively reduced the disability and mortality rates of patients and provides a reference for similar cases in the future.

| 1. | Qian ZY, Yang MF, Zuo KQ, Xiao HB, Ding WX, Cheng J. Protective effects of ulinastatin on intestinal injury during the perioperative period of acute superior mesenteric artery ischemia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:3726-3732. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jiang H, Li X, Yang T, Wang J. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage caused by rupture of superior mesenteric artery: A case report. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:2058-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang P, Song C, Lu Y. Isolated superior mesenteric artery rupture caused by abdominal trauma. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2022;23:1065-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ota H, Fukushi Y, Wada S, Fujino T, Omori Y, Kushima M. Successful treatment of uterine artery pseudoaneurysm with laparoscopic temporary clamping of bilateral uterine arteries, followed by hysteroscopic surgery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:1356-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schull MJ, Vermeulen M, Slaughter G, Morrison L, Daly P. Emergency department crowding and thrombolysis delays in acute myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:577-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Arakelian E, Swenne CL, Lindberg S, Rudolfsson G, von Vogelsang AC. The meaning of person-centred care in the perioperative nursing context from the patient's perspective - an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:2527-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jones-Akhtarekhavari J, Tribble TA, Zwischenberger JB. Developing an Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Program. Crit Care Clin. 2017;33:767-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chung SY, Tong MS, Sheu JJ, Lee FY, Sung PH, Chen CJ, Yang CH, Wu CJ, Yip HK. Short-term and long-term prognostic outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated by profound cardiogenic shock undergoing early extracorporeal membrane oxygenator-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:412-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Naito J, Nakajima T, Morimoto J, Yamamoto T, Sakairi Y, Wada H, Suzuki H, Sugiura T, Tatsumi K, Yoshino I. Emergency surgery for hemothorax due to a ruptured pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;68:1528-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gao S, Chen Y, Huang Y, Dang Y, Li Y. Acute caval thrombosis leading to obstructive shock in the early post insertion period of an inferior vena cava filter: a case report and literature review. Thromb J. 2024;22:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harries RL, Bosanquet DC, Harding KG. Wound bed preparation: TIME for an update. Int Wound J. 2016;13 Suppl 3:8-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ghamri Y, Proença M, Hofmann G, Renevey P, Bonnier G, Braun F, Axis A, Lemay M, Schoettker P. Automated Pulse Oximeter Waveform Analysis to Track Changes in Blood Pressure During Anesthesia Induction: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1222-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gao HM, Liu J, Qian SY. [Approach to diagnosis and treatment of hyperlactatemia]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2021;59:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liu T, Hu C, Wu J, Liu M, Que Y, Wang J, Fang X, Xu G, Li H. Incidence and Associated Risk Factors for Lactic Acidosis Induced by Linezolid Therapy in a Case-Control Study in Patients Older Than 85 Years. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:604680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Salazar Maya ÁM. Nursing Care during the Perioperative within the Surgical Context. Invest Educ Enferm. 2022;40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pang T, Wu Z, Zeng H, Zhang X, Hu M, Cao L. Analysis of the risk factors for secondary hemorrhage after abdominal surgery. Front Surg. 2023;10:1091162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Su Z, Guo W, Luo Y, Wang Y, Du Y. Observation on the Nursing Effect of the Whole Process in Patients with Severe Intracranial Hemorrhage. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:1546019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fabrellas N, Carol M, Palacio E, Aban M, Lanzillotti T, Nicolao G, Chiappa MT, Esnault V, Graf-Dirmeier S, Helder J, Gossard A, Lopez M, Cervera M, Dols LL; LiverHope Consortium Investigators. Nursing Care of Patients With Cirrhosis: The LiverHope Nursing Project. Hepatology. 2020;71:1106-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Devereaux PJ, Marcucci M, Painter TW, Conen D, Lomivorotov V, Sessler DI, Chan MTV, Borges FK, Martínez-Zapata MJ, Wang CY, Xavier D, Ofori SN, Wang MK, Efremov S, Landoni G, Kleinlugtenbelt YV, Szczeklik W, Schmartz D, Garg AX, Short TG, Wittmann M, Meyhoff CS, Amir M, Torres D, Patel A, Duceppe E, Ruetzler K, Parlow JL, Tandon V, Fleischmann E, Polanczyk CA, Lamy A, Astrakov SV, Rao M, Wu WKK, Bhatt K, de Nadal M, Likhvantsev VV, Paniagua P, Aguado HJ, Whitlock RP, McGillion MH, Prystajecky M, Vincent J, Eikelboom J, Copland I, Balasubramanian K, Turan A, Bangdiwala SI, Stillo D, Gross PL, Cafaro T, Alfonsi P, Roshanov PS, Belley-Côté EP, Spence J, Richards T, VanHelder T, McIntyre W, Guyatt G, Yusuf S, Leslie K; POISE-3 Investigators. Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1986-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Huang J, Qi H, Lv K, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Jin L. Development and Psychometric Properties of a Scale Measuring Barriers to Perioperative Hypothermia Prevention for Anesthesiologists and Nurses. J Perianesth Nurs. 2023;38:703-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Celik SU, Senocak R. Necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity secondary to a perforated rectosigmoid tumor. Indian J Cancer. 2021;58:603-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |