Published online Jun 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3548

Revised: April 19, 2024

Accepted: May 6, 2024

Published online: June 26, 2024

Processing time: 114 Days and 3.5 Hours

Colorectal foreign bodies are commonly encountered during surgery. They are frequently observed in men 20 to 90 years of age and have bimodal age distribution. Surgical management is necessary for cases of rectal perforation. However, surgical site infections are the most common complications after colorectal surgery.

We discuss a case of rectal perforation in a patient who presented to our hospital 2 d after its occurrence. The perforation occurred as a result of the patient inserting a sex toy in his rectum. Severe peritonitis was attributable to delayed pre

Vacuum-assisted closure was performed to treat the wound, which healed well after therapy. No complications were noted.

Core Tip: This study highlights a case of rectal perforation due to a foreign body insertion, leading to severe peritonitis due to delayed presentation. The innovative use of vacuum-assisted closure resulted in successful wound healing with no complications, emphasizing its potential effectiveness in managing such cases.

- Citation: Lin CY, Pu TW. Colon perforation with severe peritonitis caused by erotic toy insertion and treated using vacuum-assisted closure: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(18): 3548-3554

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i18/3548.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i18.3548

The reported cases of colorectal foreign bodies have involved patients 16 to 90 years of age; however, most patients are middle-aged men who have inserted foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract for autoerotic purposes[1-3]. Because perforation may lead to peritonitis and require urgent laparotomy, the first step when evaluating such patients is to determine whether perforation has occurred[2,4]. Perforation management includes debridement, distal washout, and drainage. Diversion should be performed for patients with comorbidities or major tissue damage[5].

Despite well-established preventative measures, including wound protection, postoperative maintenance of normoglycemia, and antibiotic use, colorectal surgery is associated with the highest incidence of surgical site infections (SSIs), with a rate as high as 45%[6,7]. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) may be useful for patients who require colorectal surgery because it not only isolates the wound but also improves wound healing through wound shrinkage, microdeformation at the foam–wound surface interface, fluid removal, and stabilization of the wound environment[8].

Our patient had a rectal perforation caused by foreign body penetration; however, he did not present for treatment until 2 d after its occurrence. Therefore, broad fecal peritonitis developed. After exploratory laparotomy, the surgical wound infection became more problematic; therefore, NPWT was performed.

A 32-year-old male patient who reported stomach heaviness and fever for 2 d presented to the emergency department.

The patient revealed that he had purposefully inserted a sex toy in his rectum 2 d before presentation (Figure 1).

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The patient initially showed signs of mild tachycardia, stable blood pressure, and generalized abdominal pain.

His laboratory test results indicated a white blood cell count of 6200/μL, neutrophil count of 73.3%, and lymphocyte count of 18.4%. His C-reactive protein level was 23.04 mg/dL.

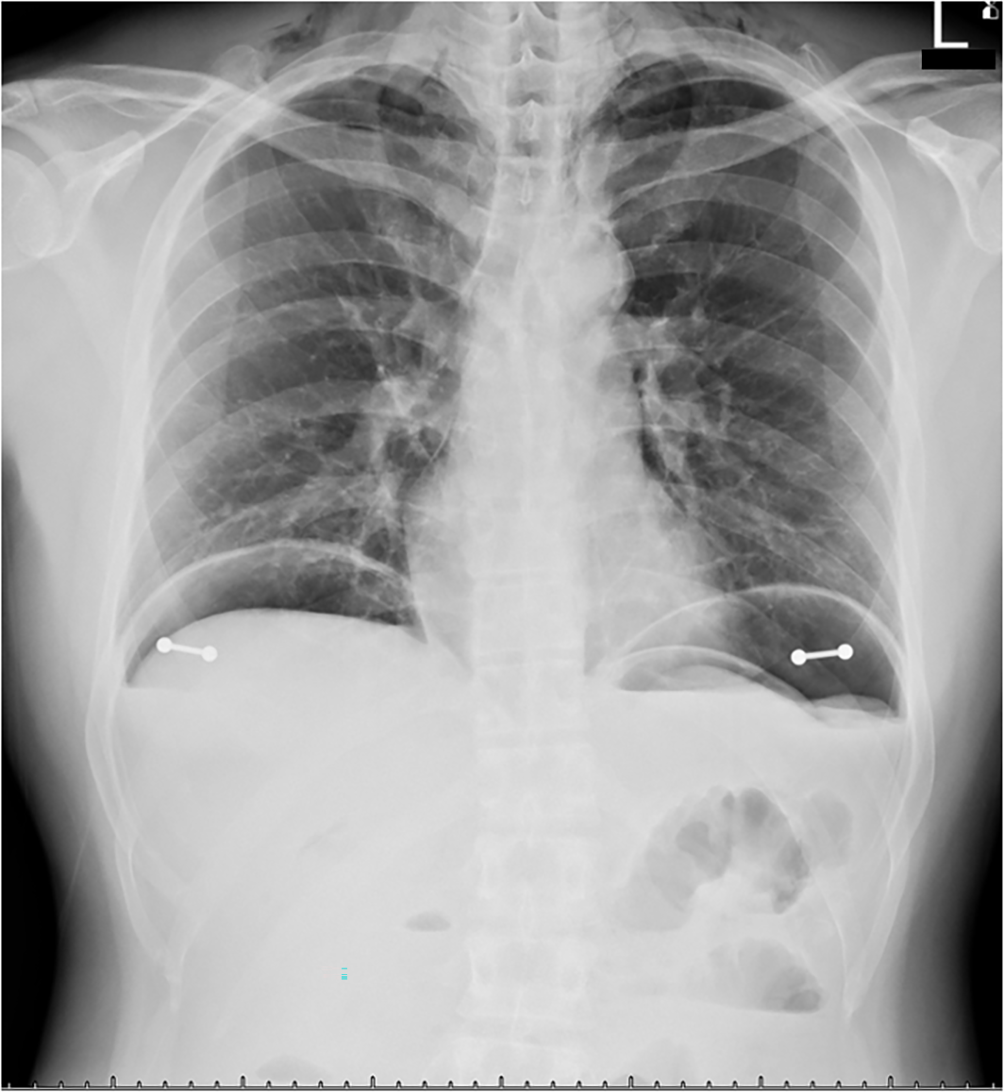

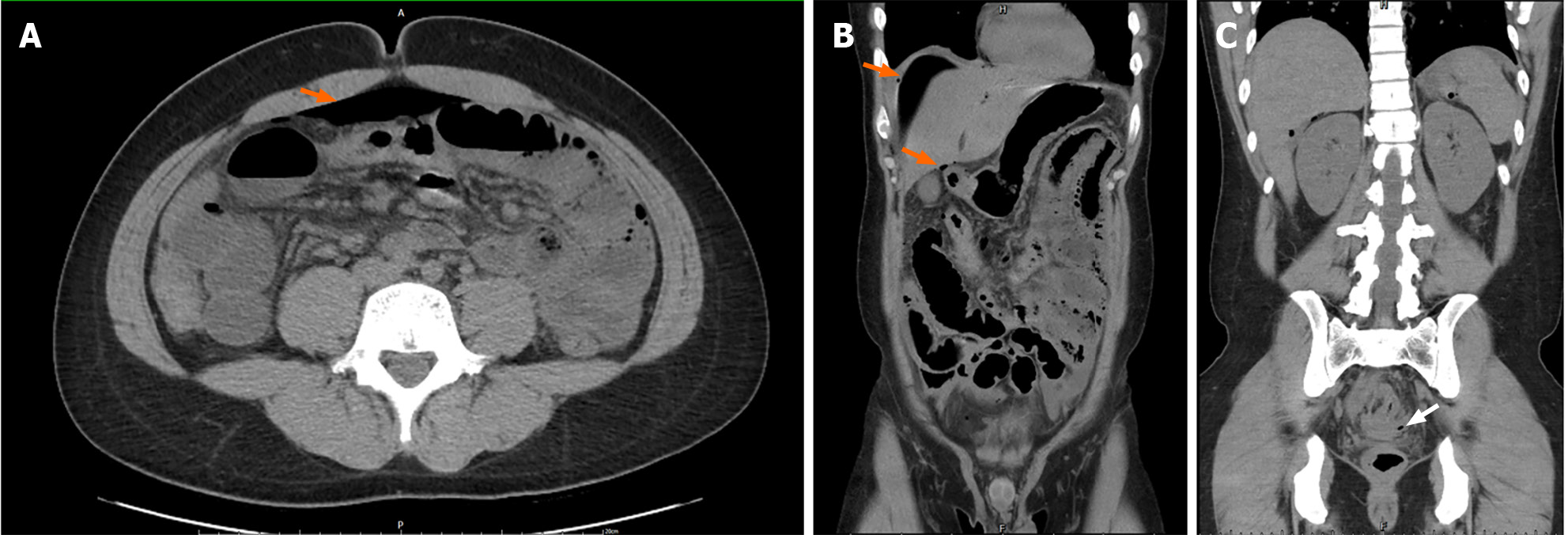

He underwent erect chest radiography, which revealed subphrenic free air, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema in the bilateral neck region (Figure 2). Abdominal radiography revealed no foreign objects. Computed tomography (CT) revealed pneumoperitoneum, which was suggestive of hollow organ perforation and mild ascites (Figure 3).

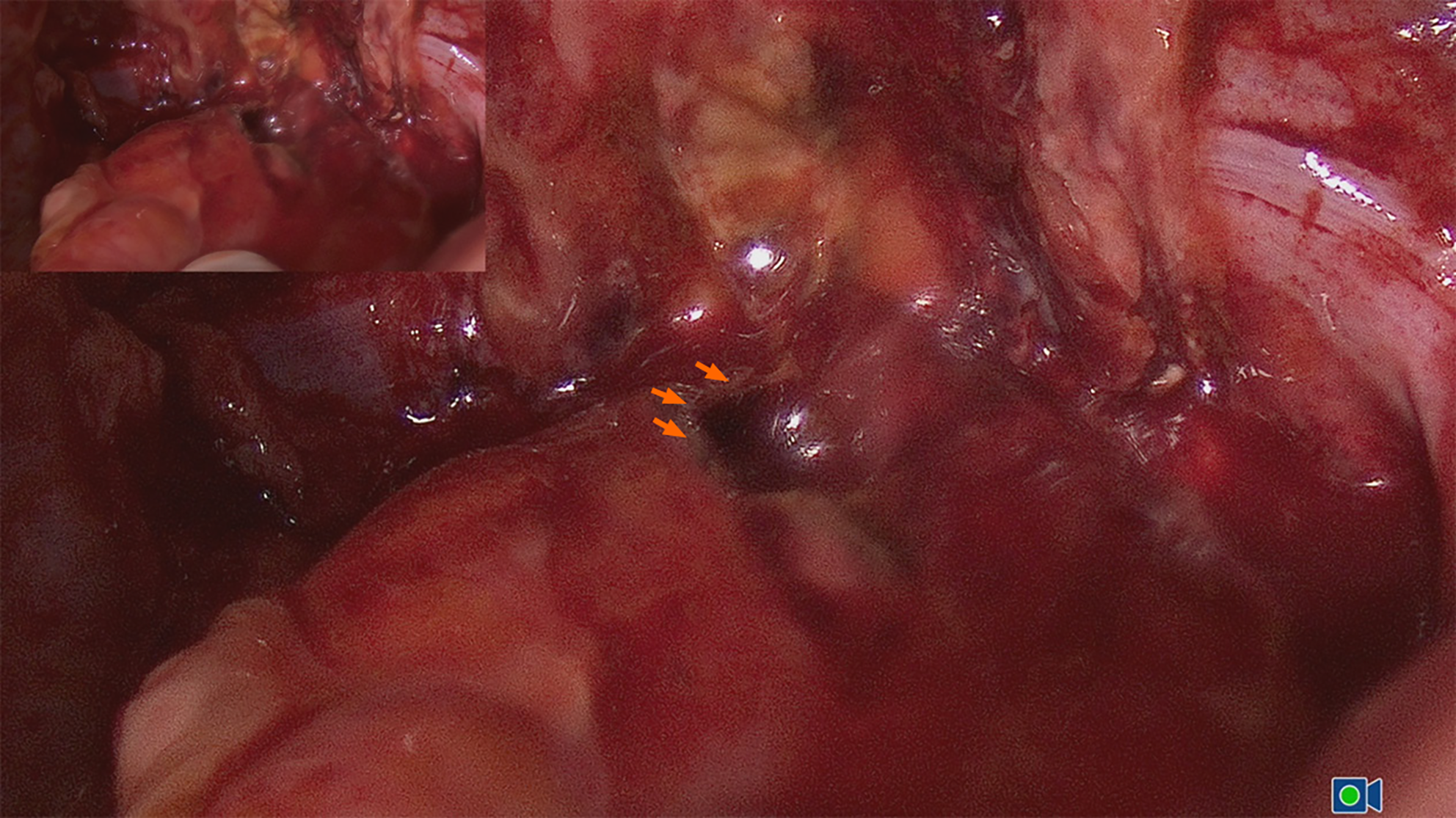

The patient provided consent for treatment, completed preoperative preparation, and underwent laparoscopy with revision to exploratory laparotomy with low anterior resection, followed by revision laparoscopy. Fecal ascites were present throughout the procedure, and a perforated hole with a hemorrhagic area with a length of 2 cm was identified at the anterior wall of the rectum 12 cm above the anal verge (Figure 4).

The final diagnosis was rectal perforation with severe peritonitis caused by erotic toy insertion and delayed presentation for medical treatment.

A perforated piece of the rectum and approximately 6 cm of the rectum were removed. The bowel was repaired with a primary anastomosis. A diverting loop ileostomy was constructed. The abdominal cavity was cleaned before it was sealed. Piperacillin and tazobactam were prescribed postoperatively and supportive management was provided.

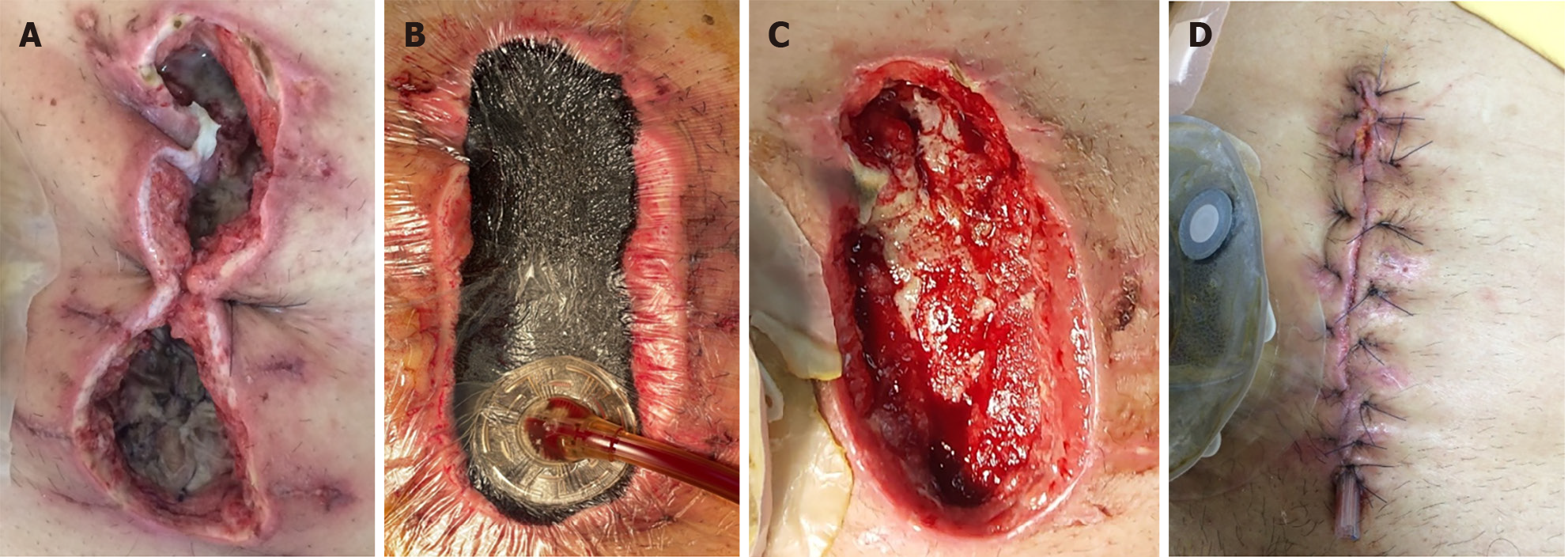

On postoperative day 3, the midline wound had not healed properly, and there was a large amount of turbid discharge. Therefore, a wet dressing containing hypochlorous acid was applied. The wound culture revealed Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Klebsiella pneumonia ssp pneumonia. On postoperative day 8, debridement was performed because of necrotic tissue in the wound. Two days later, the bottom of the wound began to exude a purulent substance with an unpleasant odor (Figure 5A). We performed vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) after debridement and removed the necrotic tissue (Figure 5B) to promote rapid healing. The surgical wound was covered with a negative pressure dressing comprising black polyurethane foam with 400- to 600-µm pores and a clear adhesive drape; constant pressure was adjusted to 125 mmHg.

Thereafter, the healed wound was checked daily for any indication of infection or other local complications. Every 3 to 4 d, we changed the dressing and performed further lavage and debridement under sterile conditions. VAC was completed 14 days after the wound bed appeared clean, granulated, contracted, and viable (Figure 5C). The entire wound was closed using a myocutaneous flap, and a Penrose drain was implanted to allow drainage. The wound healed well, and no complications were observed during his follow-up as an outpatient (Figure 5D).

According to previously reported cases of colorectal foreign bodies, the average age of patients ranges from 41 to 44 years[1,2]. The majority of these cases have involved the insertion of foreign bodies for autoerotic purposes, and the majority of these patients were middle-aged homosexual men with autoerotic implants[3].

In decreasing order of frequency, autoeroticism, concealment, attention-seeking behavior, accidents, assault, and constipation relief are the reasons why foreign bodies have been inserted in the rectum[9]. Sexual and criminal reasons are more common among younger patients, and medical reasons such as relief from constipation and prostatic massage are more common among older patients[5].

Because of cultural and social contexts, patients are frequently embarrassed about their condition and delay seeking medical treatment. They may try to hide their sexual orientation and create false reasons for their condition. To correctly identify the presence of rectal foreign bodies, medical professionals must have a strong suspicion of the patient’s condition. In up to 20% of these cases, the patients or those accompanying them to the hospital do not express the cause (insertion of a foreign body in the rectum) of the primary symptom. Symptoms include abdominal pain, constipation or obstipation, rectal bleeding comprising bright red blood, and incontinence[2,10,11].

Determining the existence of the perforation, which could have been caused by the foreign body and requires urgent laparotomy, is the first step during the evaluation of a patient with a rectal foreign body. Symptoms include severe abdominopelvic pain, tachycardia, fever, and hypotension. Laboratory investigations are unnecessary for stable patients with normal vital signs. In contrast, radiographs and CT images can reveal warning signs, such as intra-abdominal free air, and indicate whether rectal perforation has occurred. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema were also observed with a case of rectal perforation[12]. Moreover, radiography and CT examinations can help locate the foreign body if it has not yet been removed. Rigid proctoscopy or endoscopic examination may reveal the rectal injury or foreign body if it is located higher in the rectosigmoid or rectal vault[2,4].

Patients who experience rectal perforation should be admitted as trauma patients and stabilized. Intravenous fluids and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered immediately. It is necessary to insert a Foley catheter and nasogastric tube and obtain suitable blood samples for laboratory testing[4]. Perforation management includes deb

However, despite well-established preventative measures including wound protection, maintaining normoglycemia postoperatively, and antibiotic use, colorectal surgeries are associated with the highest incidence of SSIs, which can be as high as 45%[6,7]. Moreover, the presence of a stoma is an independent risk factor for postoperative SSI development[14]. When a stoma is present, the use of NPWT during colorectal surgery may be advantageous. In addition to isolating the wound, NPWT can improve wound healing through wound environment stabilization, wound shrinkage, fluid eva

Although anally inserted foreign bodies are not uncommon worldwide, few have been encountered in Asia. In the present case, the foreign body was removed when the patient visited the emergency department. However, during the 2 d before presentation, the penetrating wound led to fecal peritonitis and sepsis. SSIs are challenging after exploratory laparotomy with low anterior resection and protective ileostomy. VAC is a commonly used NPWT for infected wounds. The wound healed well after therapy, and no complications were noted.

| 1. | Ikram S, Singh S, Kallam R, Dabra A. A play that went wrong: Unique presentation of bowel perforation from an unusually large per-rectal foreign body. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Cologne KG, Ault GT. Rectal foreign bodies: what is the current standard? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2012;25:214-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Bose KS, Sarma RH. Delineation of the intimate details of the backbone conformation of pyridine nucleotide coenzymes in aqueous solution. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:1173-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goldberg JE, Steele SR. Rectal foreign bodies. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90:173-184, Table of Contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coskun A, Erkan N, Yakan S, Yıldirim M, Cengiz F. Management of rectal foreign bodies. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wick EC, Vogel JD, Church JM, Remzi F, Fazio VW. Surgical site infections in a "high outlier" institution: are colorectal surgeons to blame? Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:374-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anthony T, Murray BW, Sum-Ping JT, Lenkovsky F, Vornik VD, Parker BJ, McFarlin JE, Hartless K, Huerta S. Evaluating an evidence-based bundle for preventing surgical site infection: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2011;146:263-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang C, Leavitt T, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Effect of negative pressure wound therapy on wound healing. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51:301-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Clarke DL, Buccimazza I, Anderson FA, Thomson SR. Colorectal foreign bodies. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cohen JS, Sackier JM. Management of colorectal foreign bodies. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:312-315. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kurer MA, Davey C, Khan S, Chintapatla S. Colorectal foreign bodies: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:851-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yang J, Liu WQ, Dong J, Wen ZQ, Zhu Z, Li WL. Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum and extensive subcutaneous emphysema resulting from endoscopic mucosal resection secondary to colonoscopy: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2763-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yildiz SY, Kendirci M, Akbulut S, Ciftci A, Turgut HT, Hengirmen S. Colorectal emergencies associated with penetrating or retained foreign bodies. World J Emerg Surg. 2013;8:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Elective colon and rectal surgery differ in risk factors for wound infection: results of prospective surveillance. Ann Surg. 2006;244:758-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ma Z, Shou K, Li Z, Jian C, Qi B, Yu A. Negative pressure wound therapy promotes vessel destabilization and maturation at various stages of wound healing and thus influences wound prognosis. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:1307-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sahebally SM, McKevitt K, Stephens I, Fitzpatrick F, Deasy J, Burke JP, McNamara D. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Closed Laparotomy Incisions in General and Colorectal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e183467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |