Published online Jun 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i17.3214

Revised: April 25, 2024

Accepted: May 16, 2024

Published online: June 16, 2024

Processing time: 105 Days and 13.3 Hours

We report a rare case of cervical spinal canal penetrating trauma and review the relevant literatures.

A 58-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with a steel bar penetrating the neck, without signs of neurological deficit. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated that the steel bar had penetrated the cervical spinal canal at the C6–7 level, causing C6 and C7 vertebral body fracture, C6 left lamina fracture, left facet joint fracture, and penetration of the cervical spinal cord. The steel bar was successfully removed through an open surgical procedure by a multidisciplinary team. During the surgery, we found that the cervical vertebra, cervical spinal canal and cervical spinal cord were all severely injured. Postoperative CT demonstrated severe penetration of the cervical spinal canal but the patient returned to a fully functional level without any neurological deficits.

Even with a serious cervical spinal canal penetrating trauma, the patient could resume normal work and life after appropriate treatment.

Core Tip: Cervical spinal canal penetrating trauma is rare. We present a rarer case of a serious cervical spinal canal penetrating trauma caused by a steel bar in a building site. Computed tomography demonstrated that the steel bar penetrated the cervical spinal canal at the C6-7 level, without obvious signs of vascular structure involvement. The steel bar was successfully removed through an open surgical procedure by a multidisciplinary team. The patient returned to a fully functional level without any neurological deficits. No similar report has been found previously. This case even challenges the cognition about the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology today.

- Citation: Zhang Q, Ding T, Gu XF, Liu Y. Steel bar penetrating cervical spinal canal without neurological injury: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(17): 3214-3220

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i17/3214.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i17.3214

Civilian stab wounds resulting in spinal canal injuries are rare and mostly associated with spinal cord injuries (SCIs). These injuries are usually called nonmissile penetrating spinal injuries (NMPSIs). When compared to other mechanisms, Africa has a higher incidence of NMPSIs in some reports[1,2]. These lesions commonly cause complete/incomplete neurological deficits, although nearly two thirds of patients show good functional recovery[2].

Cervical NMPSIs caused by different foreign bodies such as sharp wood[2], knife[3], chopstick[4], screwdriver[5] and steel wire[6,7], are rarer and carry a high morbidity and mortality. In all these cases, the foreign bodies are small and sharp, penetrate the cervical spinal canal, causing varying degrees of cervical SCI, and patients have different degrees of neurological deficit.

We present the case of a 58-year-old man who was seriously penetrated by a steel bar through cervical spinal canal. After surgical treatment, the patient returned to a fully functional level without any neurological deficits. Steel bars on construction site are blunt and heavy, and may cause serious multiple tissue contusion, but there are only rare reports of penetrating injury of the cervical spinal canal. To our knowledge, there is no report of serious cervical spinal canal and cervical spinal cord penetration without neurological deficits.

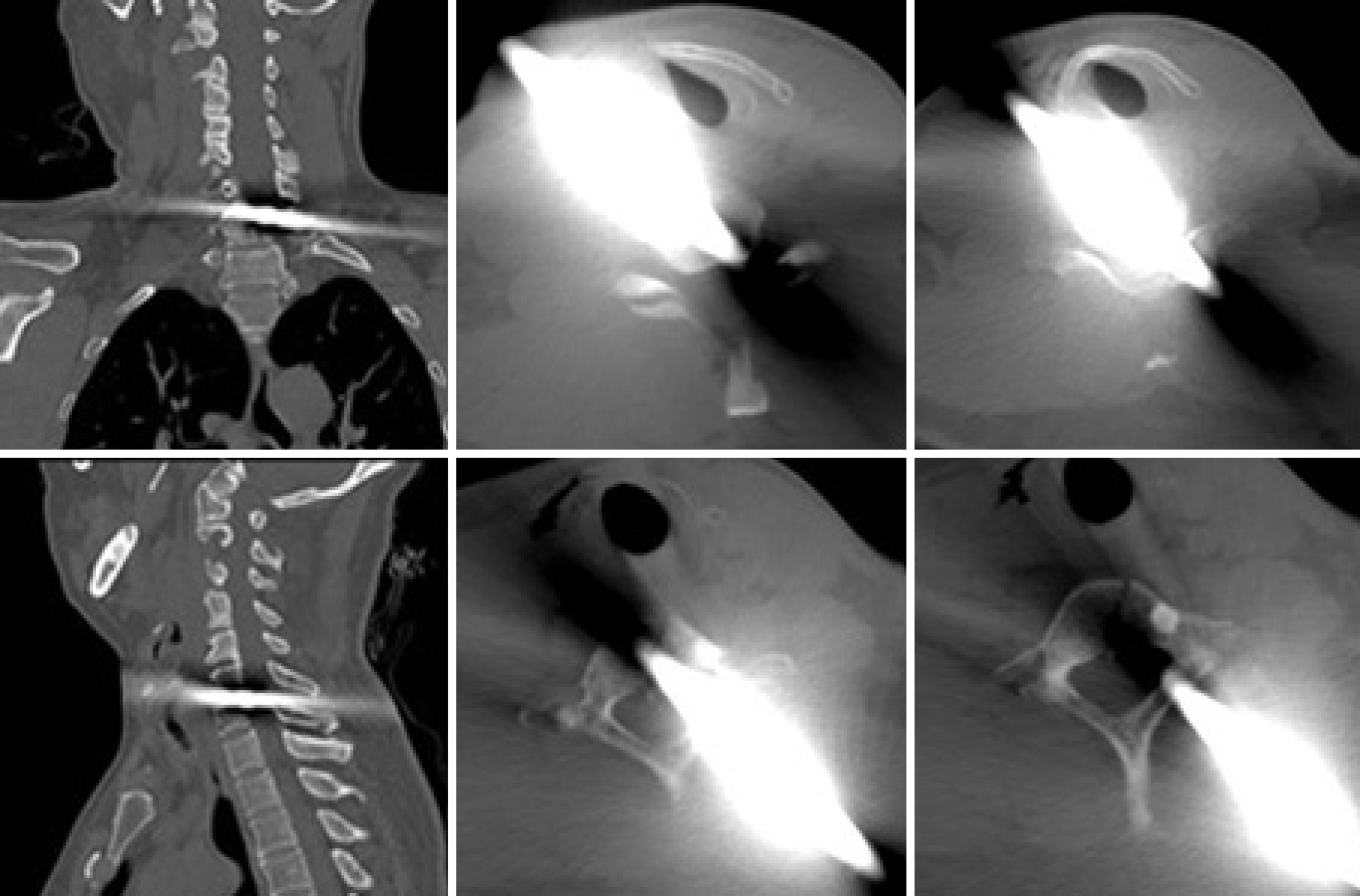

A 58-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency department with a steel bar penetrating the neck (Figure 1). The patient was injured accidentally in a building site, with a steel bar entering via the right front of the neck, then penetrating the cervical spine, with the head of the bar stopping at the posterior subcutaneous tissue of the left shoulder, not piercing through the skin.

The patient’s vital signs were stable, and physical examination showed normal body sensation, muscle strength, limb tension, and tendon reflex of the upper and lower extremities. Sacral sparing of sensory function was retained and bilateral pyramidal signs were negative. We did not find any signs of neurological deficit.

No obvious abnormalities were found.

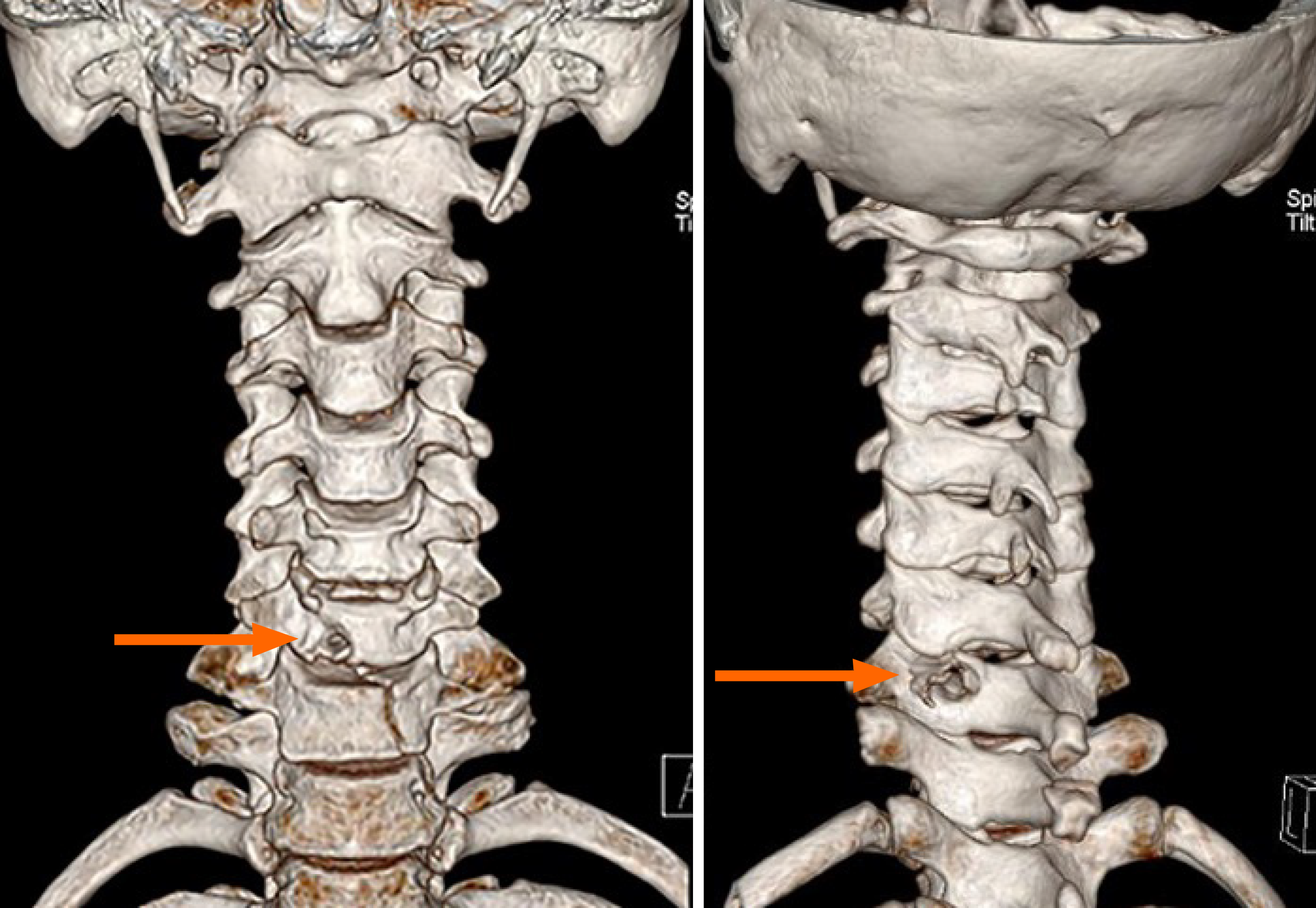

Computed tomography (CT) and 3D reconstruction were performed for preoperative evaluation. The steel bar had penetrated the cervical spinal canal at the C6–7 level, causing C6 and C7 vertebral body fracture, C6 left lamina fracture and left facet joint fracture (Figure 2). Although the metal artifacts were obvious on CT, we found that the steel bar had penetrated the cervical spinal canal, which may have caused serious cervical SCI. We could not exclude the possibility of carotid artery, jugular vein, trachea, esophagus and vertebral artery injury.

The final diagnosis was cervical spinal canal penetrating trauma by a steel bar.

Surgical treatment was performed by a multidisciplinary team in our hospital. A large amount of blood was prepared, which can be used in the event of massive bleeding. Tracheotomy was performed under local anesthesia, and general anesthesia was applied, with the ventilator working through the tracheotomy tube. A longitudinal oblique cut approximately 6 cm long was made around the steel bar, and we dissociated the soft tissue near the steel bar, and exposed the cervical vertebra gradually. The carotid artery and jugular vein were not injured, and we found no signs of injury to the trachea and esophagus. Subsequently, we gently pulled out the steel bar while rotating back and forth (Figure 3), and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flowed out of the bony cavity. Debridement was performed, and we dissociated the soft tissue to fill and repair the bone hole in order to prevent CSF leakage. The patient's vital signs were stable during the entire procedure. The wound was closed layer by layer and a drainage tube was left to maintain proper negative stress suction. An indwelling gastric tube was used to provide gastrointestinal nutrition postoperatively. Immobilization of the injured cervical spine was achieved by skull traction with a 6-kg weight.

The patient intravenously received ceftriaxone for 7 d, which could penetrate the blood–brain barrier, to prevent infection. Intravenous methylprednisolone (240 mg/d) was administered for 3 d because of the cervical SCI. Albumin and mannitol were also given for dehydration to reduce possible cervical cord edema.

After recovery from general anesthesia, the patient’s body sensation, muscle strength, limb tension, and tendon reflex of the upper and lower extremities were all normal; bilateral pyramidal signs were negative; and we did not find any signs of cervical SCI.

There was a small amount of bloody fluid but no CSF flowing out of the drainage tube, which was removed 48 h after surgery. CT was performed to ensure that there was no tracheal injury. The tracheostomy cannula was blocked and removed 5 d after the operation. Similarly, the gastric tube was not removed until esophageal injury was excluded by esophagoscopy 3 d after the operation, and the patient gradually returned to normal eating. The wound healed well within 1 wk.

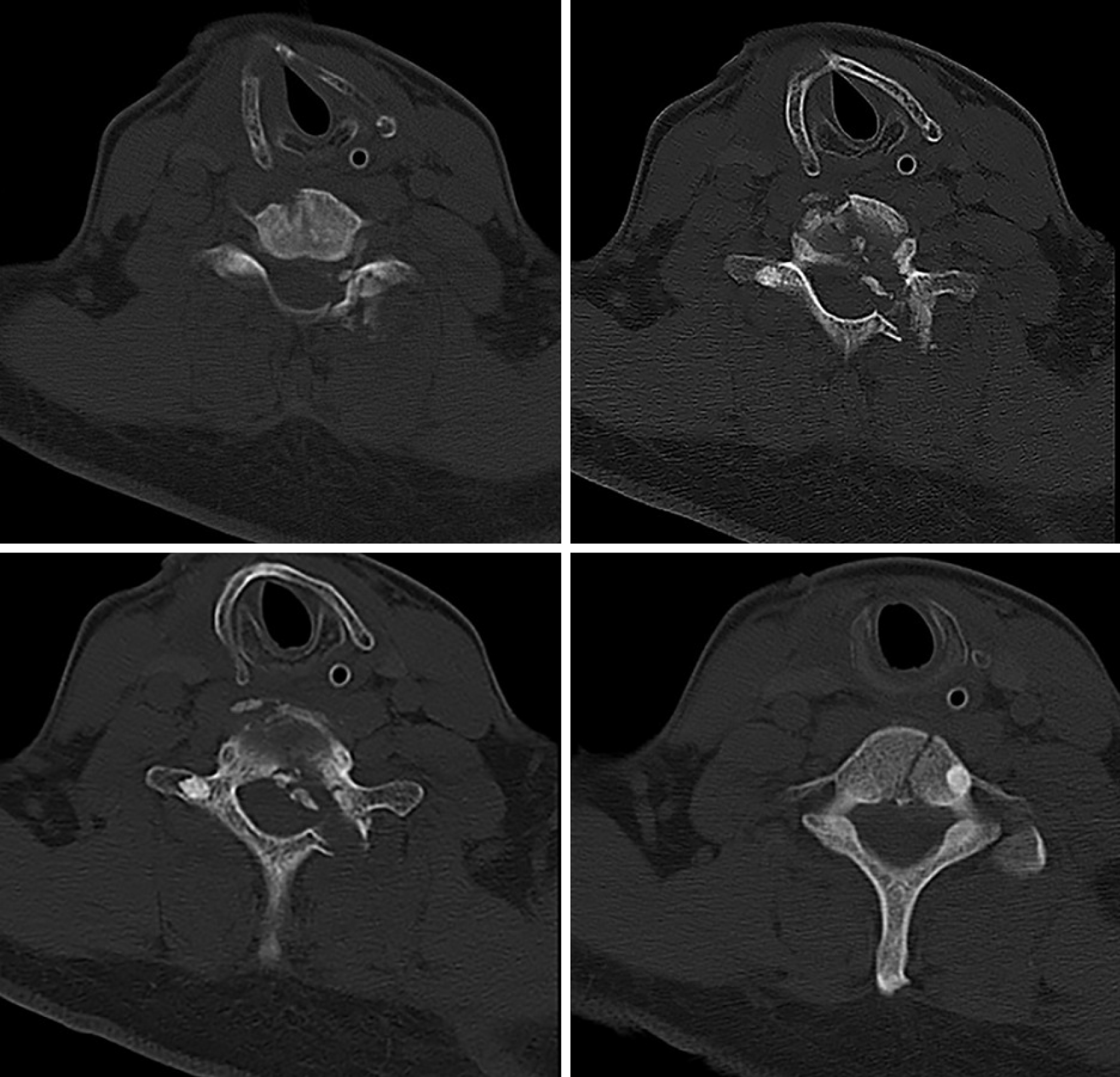

CT and 3D reconstruction were performed for postoperative evaluation. We found that the steel bar had penetrated the right side of the cervical spinal canal at the C6–7 level, which caused C6 and C7 vertebral body fracture, C6 left lamina fracture and left facet joint fracture (Figures 4 and 5). In the horizontal plane of spinal canal imaging, we found the track of the steel bar, which occupied nearly half of the cervical spinal canal (Figure 5).

The skull traction was removed 3 wk after the operation, and a head, neck and chest fixing brace was used to achieve immobilization of the injured cervical spine, while gently raising the patient’s upper body to a sitting position. As there was no obvious discomfort, the patient resumed walking activity progressively 4 wk after the operation.

The patient was followed up for 2 years. The head, neck and chest fixing brace was replaced by a Philadelphia cervical collar 8 wk after the operation, which was removed 4 wk later. The patient performed normal daily activities during the follow-up, and returned to the construction site for work 4 mo after the operation. There was no symptoms of cervical intramedullary abscess during the follow-up.

Cervical NMPSIs are rare. There are reports of cervical penetrating injuries caused by different foreign bodies, such as sharp wood[2], knife[3], chopstick[4], screwdriver[5], and steel wire[6,7]. The patients exhibited varying degrees of cervical SCI, or even died eventually.

Steel bars on construction sites may also cause penetrating injury in some extreme accidents[8]. However, in all the cases reported, the cervical vertebral canal and cervical spinal cord were not seriously violated. Steel bars are blunt and heavy and may cause serious multiple tissue contusion, but there are rarely reports on penetrating injury of the cervical spinal canal, unlike injuries cause by the foreign bodies mentioned above[2-7]. The steel bar’s surface is rough and rusty, which result in a high risk of injury to adjacent blood vessels and nerves during the removal. For our patient, although there were no signs of vascular injury or neurological deficit, management of the steel bar was challenging because the removal may cause neurological sequelae[9].

There are no international consensus guidelines on NMPSIs owing to their low incidence; however, as these injuries are potentially life-threatening, the treatment approach should follow the procedures for advanced trauma life support[10].

Before the operation, CT and 3D reconstruction were performed, which showed serious injury to the cervical vertebral canal. As the patient’s vital signs and other monitored parameters all appeared normal, and there was not massive active bleeding from the wound, we speculated that there was no serious injury to the blood vessels. However, we could not exclude minor damages to the blood vessels, which might be blocked by the steel bar, and could cause fatal bleeding during the removal of the steel bar. We also could not exclude iatrogenic vascular injury during surgery, which may also cause massive hemorrhage. Therefore, we prepared a large amount of blood before the operation, and an experienced vascular surgeon was asked to join us while performing the surgery.

Lack of airflow from the wound and preoperative CT indicated that there was no severe tracheal injury. However, we could not exclude a minor damage to the trachea. Blood can enter the trachea through sites of minor injury as severe hemorrhage occurs during surgery, and the patient may die of asphyxia. Therefore, tracheotomy was performed before surgery, and the patient was ventilated through the tracheotomy tube during the operation.

During the surgery, we found the steel bar passing through the soft tissue anterior the neck, the path was just through which we perform the anterior cervical surgery. The cervical vertebra, cervical spinal canal and cervical spinal cord were all severely injured. We pulled out the steel bar directly, and CSF flowed out of the bony cavity. After complete debri

During the operation, we found that the carotid artery and jugular vein were not injured, nor did we find any signs of injury to the trachea and esophagus. It has been reported that surgical exploration adds little benefit, if any[11,12]. The steel bar was rusty and dirty, and any unnecessary surgical explorations might increase the probability of infection; therefore, we did not undertake surgical exploration to confirm whether there was tracheal or esophageal injury. Also, even slight injury may cause tracheal or esophageal mediastinal fistula, causing refractory mediastinal infection, which can be fatal. An indwelling gastric tube was used to provide gastrointestinal nutrition postoperatively. Esophagoscopy was performed 3 d after the operation to ensure that there was no esophageal injury, then the gastric tube was removed and the patient gradually returned to completely normal eating. Until CT scan and tracheal virtual endoscopy was performed after the operation, to exclude tracheal injury, the tracheostomy cannula was removed 5 d after the operation.

In this patient, the heavy steel bar had penetrated the cervical spinal canal. CT showed that nearly half of the cervical spinal canal was involved, and this injury was very likely to cause serious cervical SCI, which leads to a high probability of paraplegia, or even death. However, before and after the operation, the patient showed no signs of neurological deficit and preserved a fully functional nervous system. This even challenges current understanding of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology.

Late complications such as intramedullary abscess, myelopathy, neurological deficit and spinal instability have been reported due to penetrating injury to the spine[13], but none of these was present in our patient. The patient returned to a fully functional level without any neurological deficits.

Penetrating injury of the cervical spinal canal is rare, and appropriate examinations and adequate preparation should be performed before surgical intervention. A good operative strategy should firstly save the patient’s life, and then minimize tissue injury during the operation to preserve limb function. For penetrating cervical spinal canal injury caused by a foreign body, without neurological deficit, direct withdrawal may be a good choice.

| 1. | Peacock WJ, Shrosbree RD, Key AG. A review of 450 stabwounds of the spinal cord. S Afr Med J. 1977;51:961-964. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Waters RL, Sie I, Adkins RH, Yakura JS. Motor recovery following spinal cord injury caused by stab wounds: a multicenter study. Paraplegia. 1995;33:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koruga N, Soldo Koruga A, Butković Soldo S, Kondža G. POSTERIOR PENETRATING INJURY OF THE NECK: A CASE REPORT. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57:776-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamaguchi S, Eguchi K, Takeda M, Hidaka T, Shrestha P, Kurisu K. Penetrating injury of the upper cervical spine by a chopstick--case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2007;47:328-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rabiu TB, Aremu AA, Amao OA, Awoleke JO. Screw driver: an unusual cause of cervical spinal cord injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang Z, Liu Y, Qu Z, Leng J, Fu C, Liu G. Penetrating injury of the spinal cord treated surgically. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e1136-e1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Borgstedt-Bakke JH, Duel P, Rasmussen MM. Penetrating cervical traumatic spinal cord injury due to lawn mowing: an unusual case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2018;160:1917-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li Z, Chen J, Qu X, Duan L, Huang C, Zhang D, Hou L. Management of a Steel Bar Injury Penetrating the Head and Neck: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:168-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shahlaie K, Chang DJ, Anderson JT. Nonmissile penetrating spinal injury. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;4:400-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Villarreal-García FI, Reyes-Fernández PM, Martínez-Gutiérrez OA, Peña-Martínez VM, Morales-Ávalos R. Direct withdrawal of a knife in the lumbar spinal canal in a patient without neurological deficit: case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. 2018;4:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Velmahos GC, Degiannis E, Hart K, Souter I, Saadia R. Changing profiles in spinal cord injuries and risk factors influencing recovery after penetrating injuries. J Trauma. 1995;38:334-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xia X, Zhang F, Lu F, Jiang J, Wang L, Ma X. Stab wound with lodged knife tip causing spinal cord and vertebral artery injuries: case report and literature review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37:E931-E934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jones FD, Woosley RE. Delayed myelopathy secondary to retained intraspinal metallic fragment. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:979-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |