Published online Jun 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2862

Revised: February 28, 2024

Accepted: April 10, 2024

Published online: June 6, 2024

Processing time: 147 Days and 22.8 Hours

Rectal mucosal melanoma is a rare and highly aggressive disease. Common symptoms include anal pain, an anal mass, or bleeding. As such, the disease is usually detected on rectal examination of patients with other suspected anorectal diseases. However, due to its rarity and nonspecific symptoms, melanoma of the rectal mucosa is easily misdiagnosed.

This report describes the case of a 58-year-old female patient who presented with a history of blood in her stool for the prior one or two months, without any identifiable cause. During colonoscopy, a bulge of approximately 2.2 cm × 2.0 cm was identified. Subsequently, the patient underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to characterize the depth of invasion of the lesions. EUS suggested a hypoechoic mucosal mass with involvement of the submucosal layer and heterogeneity of the internal echoes. Following surgical intervention, the excised tissue samples were examined and confirmed to be rectal malignant melanoma. The patient recovered well with no evidence of recurrence during follow-up.

This case shows that colonoscopy with EUS and pathological examination can accurately diagnose rare cases of rectal mucosal melanoma.

Core Tip: Rectal mucosal melanoma is an exceptionally rare cancer that is more aggressive than other melanomas of the same stage. It’s vague symptoms, such as anal pain or rectal bleeding, especially in the early stages, lead to common mis

- Citation: Xiong ZE, Wei XX, Wang L, Xia C, Li ZY, Long C, Peng B, Wang T. Endoscopic ultrasound features of rectal melanoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(16): 2862-2868

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i16/2862.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2862

Rectal mucosal melanoma is a rare form of melanoma, accounting for only 1% to 2% of melanomas. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides a better assessment of the depth of infiltration than computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which makes it more useful for evaluating clinical staging and selecting surgical methods. In this article, we present the case of a patient with a rarely observed rectal mucosal melanoma and a literature review of the topic.

A 58-year-old woman presented to our outpatient anorectal surgery clinic with a history of blood in her stools for the prior one or two months with no apparent cause.

Once a day for the previous month, the patient had produced soft stools that had a small amount of blood adhering to the surface of the stool as well as a small amount of mucus. However, the patient denied any other symptoms connected to the digestive system, including stomach pain, pus and blood in the stool and loss of appetite.

The patient had a history of bronchitis, esophagitis, and gastric ulcers. She had undergone surgery for a compression fracture of the lumbar spine (L2) in June 2018 (details unknown).

The patient had no family history of rectal malignant melanoma or of psychological or genetic disorders.

After admission, relevant auxiliary examinations were performed, and the patient had no further abnormal signs. Her general condition was good, and her vital signs were within physiologic limits.

Laboratory examinations revealed that the patient’s bloodwork was within normal limits. Stool routine tests were positive for (+) occult blood.

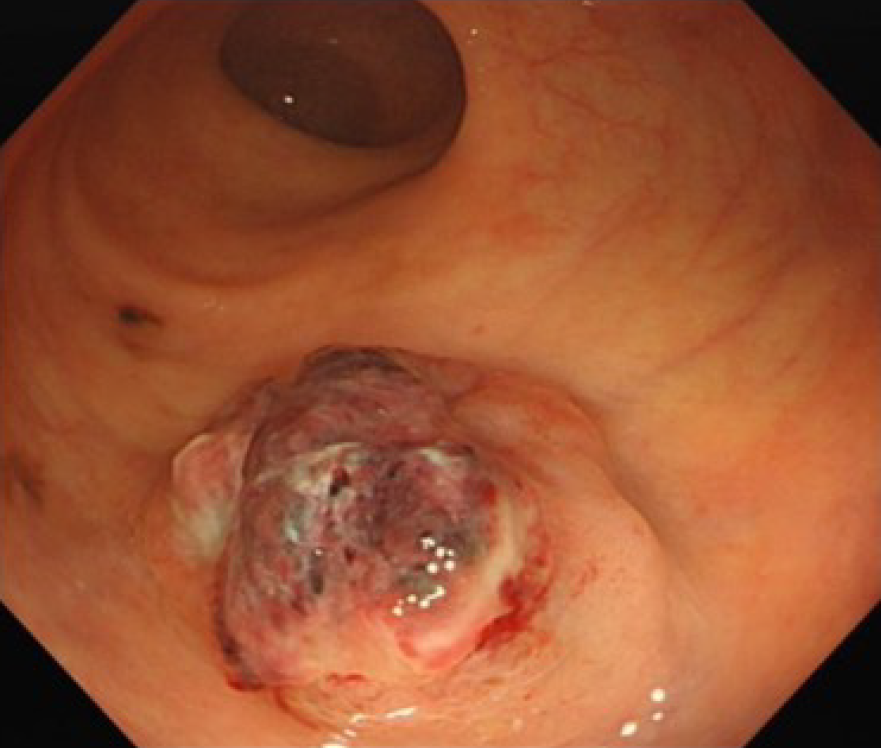

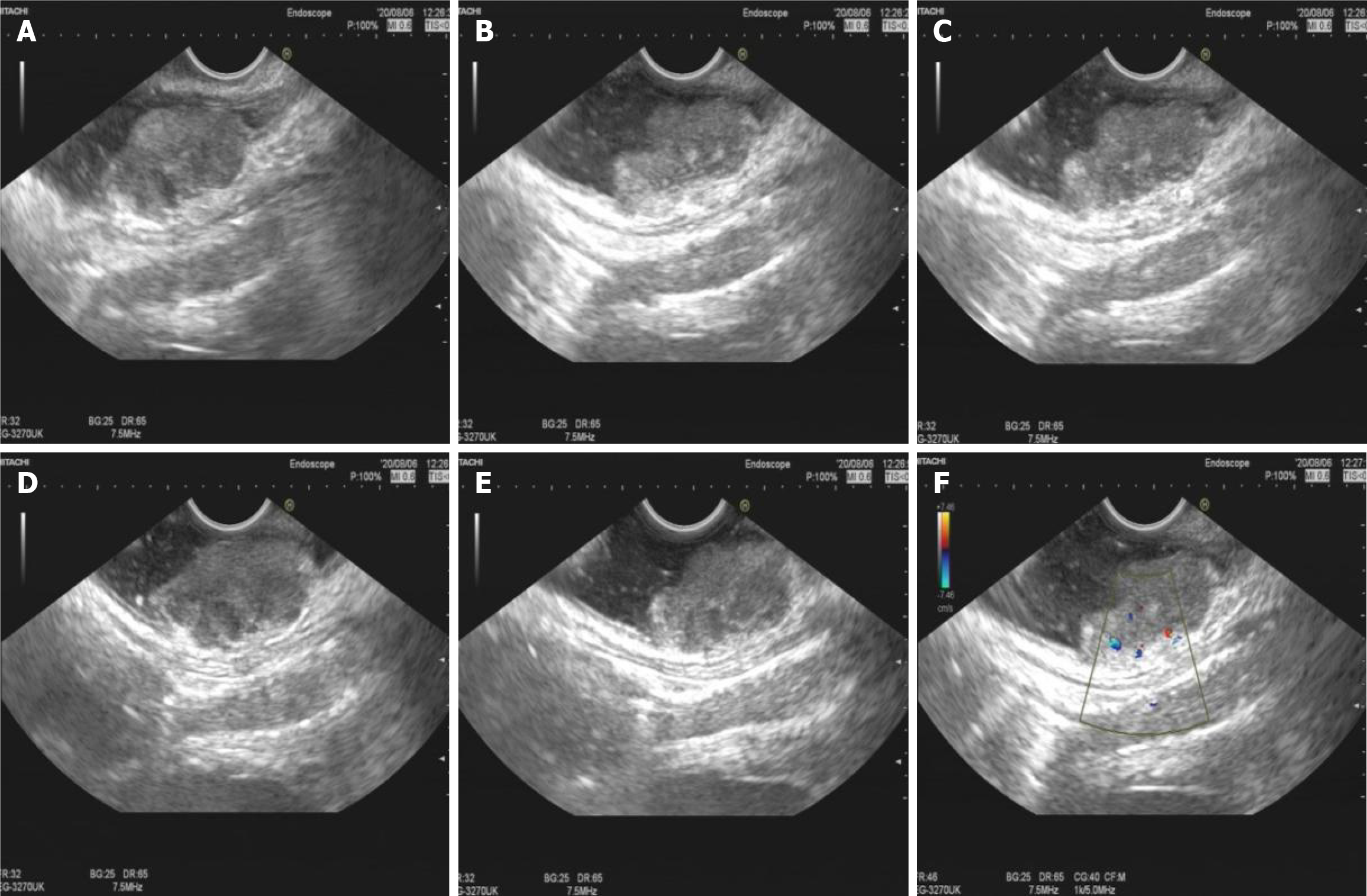

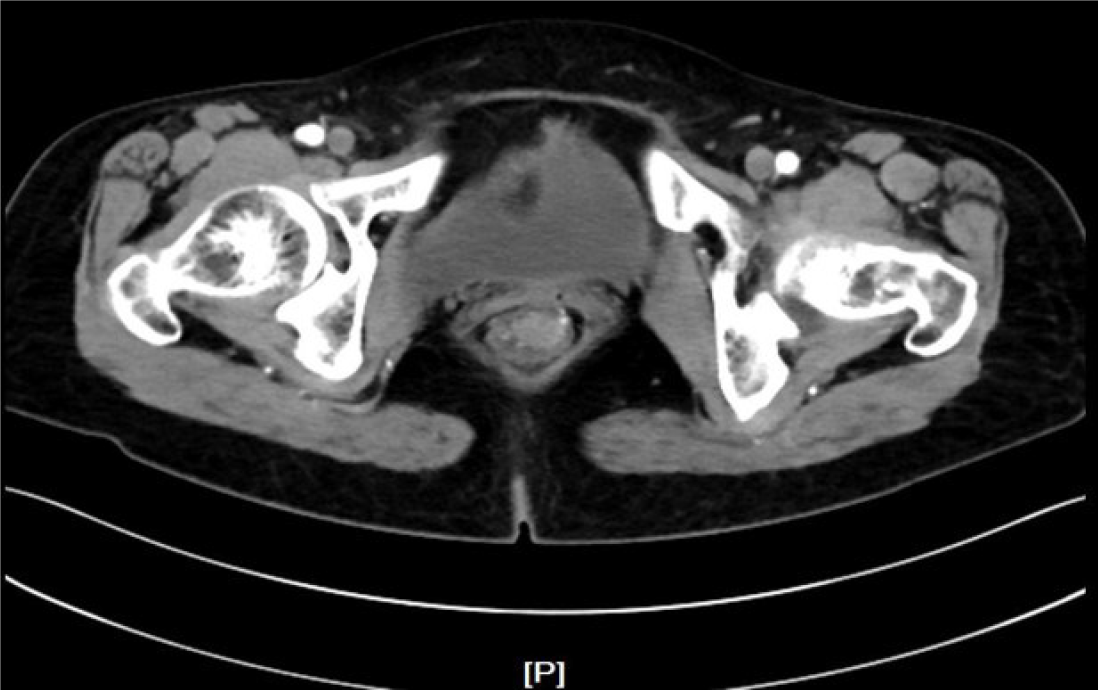

A bulging tumor of approximately 2.2 cm × 2.0 cm with a purplish-red apex and clear boundaries was identified approximately 8 cm from the anus by colonoscopy (Figure 1). EUS suggested a hypoechoic mucosal mass with involvement of the submucosal layer and heterogeneity of the internal echoes (Figure 2A-E). Color Doppler showed localized blood, and the intrinsic muscle layer was still intact (Figure 2F). Abdominopelvic CT indicated nodular enhancement foci in the rectum, and fortunately, no definitively enlarged lymph nodes or metastatic foci were identified throughout the abdomen (Figure 3).

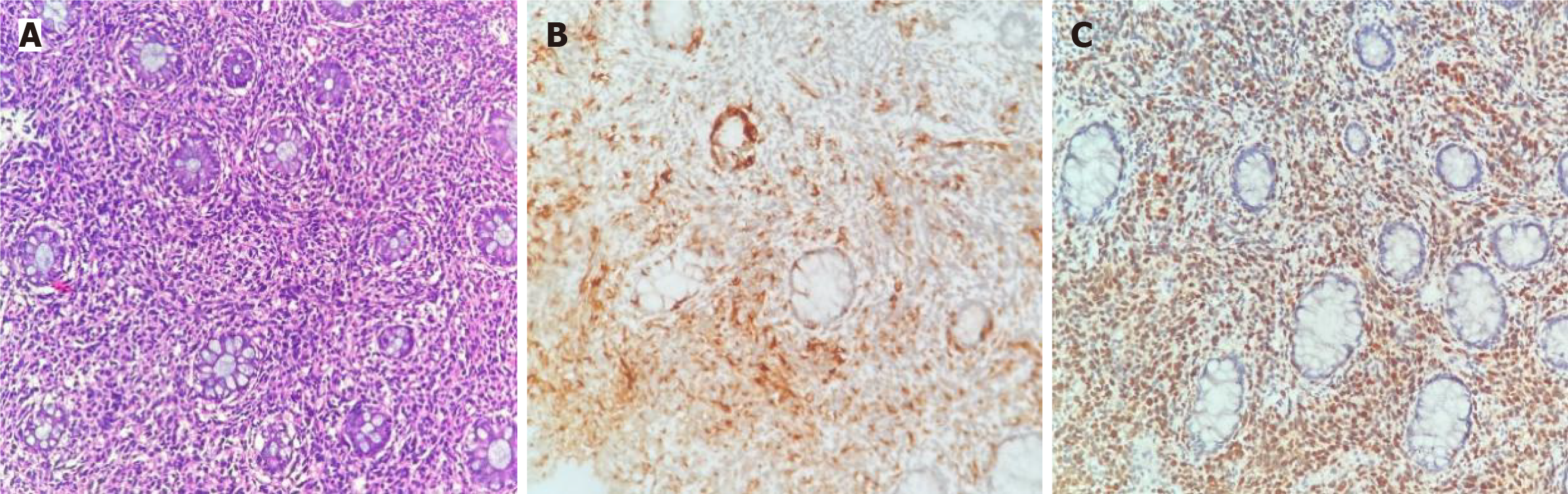

Local biopsy for pathology and immunohistochemistry showed positivity for HMB45 and S-100 (Figure 4), and the results verified that the tumor was a rectal malignant melanoma.

The patient was subsequently transferred to another hospital for wide local excision (LE) and received temozolomide combined with cisplatin adjuvant chemotherapy.

No local lymph node metastasis was observed either surgically or pathologically. The patient underwent surgical treatment and was followed up for 2 years, with no recurrence or metastasis exhibited.

The incidence rate of malignant melanoma is 21.9-55.9 per 100000 people in Western countries[1] and 0.2-0.65 per 100000 people in Asia[2]. It is commonly held that the development of melanoma is associated with intermittent high-intensity ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, genetics and other factors[3]. UV radiation may induce melanoma through direct mutagenic effects on DNA, stimulation of skin cells to produce growth factors and other effects[4]. However, in Asian populations, the primary foci of malignant melanoma are usually located in the heel, metacarpal, and subungual areas that are seldom exposed to UV radiation[1,5-7], which indicates that the development of malignant melanoma is not related to UV radiation. Indeed, the cause may be related to trauma and regions of physical stress[8,9]. In 2018, the World Health Organization classified melanomas into sun-related etiologies and non-sun-related melanomas, determined by their mutational features, anatomical sites and epidemiology. Sun-related melanomas include superficial diffuse melanoma, malignant freckle-like maculopathy and connective hyperplastic melanoma. The "nonsunlight" category includes melanomas of the extremities, some melanomas in congenital nevi, melanomas in blue nevi, Spitz melanomas, mucosal melanomas (MM), and uveal melanomas[10]. This discussion focuses on MM. Primary mucosal melanoma was identified for the first time in 1859 by Weber[11]. Mucosal melanoma is an extremely rare illness. The incidence of mucosal melanoma varies relatively significantly among different ethnic groups. Among the Caucasian population, MM account for approximately 1%-2% of all melanomas. However, the incidence of this disease is as high as 22.6% in China, which may be related to the lower incidence of cutaneous melanoma in China[12]. The main primary sites of MM in China are the nasal cavity, oral cavity, anorectum and genitourinary tract[13,14]. Due to their insidious location, these lesions usually present with bleeding, pain or discomfort as they form large tumors that invade and destroy surrounding tissues[10]. Malignant MM are more aggressive and have a worse prognosis than melanomas of other organs. Moreover, since their risk factors are not related to UV light, and there is no evidence of the role of chemical carcinogens or viral pathogens, how to prevent mucosal melanoma is also unknown[10].

Melanocytes are specialized cells whose primary role is to produce melanin, which acts as a barrier to protect DNA from UV radiation. Skin melanocytes are derived from dorsally migrating neural crest cells and ventrally migrating neural precursor cells[15]. Most melanocytes of ectoderm origin in vertebrates are located in the epidermis and dermis of the skin; however, they are also present in many other locations, including the eye, mucous membranes, and soft brain membranes[16]. Melanocytes of endodermal origin account for a small proportion of melanocytes, such as those in the nasopharynx, larynx, trachea bronchus and esophagus, which may explain the difference in the incidence of melanomas of the two different origins[17]. Furthermore, these cells are often found at the mucocutaneous junction and were once thought to be responsible for the extended formation of melanin in the skin. The presence of melanocytes has been demonstrated in mucous membranes; however, the role and function of mucosal melanocytes appear to be unclear.

MM mainly include mucosal melanoma of the head and neck, mucosal melanoma of the female genitalia and mucosal melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract (MMG).

MMGs can arise in any area of the gastrointestinal tract, but most usually originate from the anal canal (31.4%), rectum (22.2%), stomach (2.7%), oropharynx (2.3%), small bowel (2.3%), gallbladder (1.4%) or colon (0.9%)[18]. Esophageal melanoma can cause severe dysphagia due to ulcers[18] but can also lead to retrosternal pain, weight loss, and, in rare cases, vomiting blood or black stools[19]. Symptoms of gastric mucosal melanoma are nonspecific and include abdominal pain, weight loss, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia[20]. Melanoma of the small intestinal mucosa is most often secondary to metastases from melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract and usually presents with nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal pain, weight loss, gastrointestinal hemorrhage with secondary anemia and intussusception[21]. Symptoms of anorectal melanoma include blood in the stool, anal pain or discomfort, and anal mass or prolapse of a rectal mass[18]. The challenge in diagnosing MMG is that its early symptoms are usually insidious and nonspecific. Especially in the early stages, the lack of melanin discolouration and melanin deposition leads to misdiagnosis. EUS features of gastrointestinal melanoma include a hypoechoic mass beginning in the mucosal layer, indicating thickening of the mucosal layer, which may infiltrate into the submucosal layer, interrupting the submucosal layer until it involves the intrinsic muscularis propria. EUS provides a better assessment of the depth of infiltration than does CT or MRI, which makes it more useful for evaluating clinical staging and selecting surgical methods[18].

The definitive diagnosis of mucosal melanoma relies on histopathological and immunohistochemical findings. Biopsy of the lesion is followed by histopathological and immunohistochemical examination to establish the diagnosis. Melanoma has a wide range of histological features resembling epithelial, hematological, mesenchymal and neural tumors. The primary lesion is characterized by nests and single growths of atypical melanocytes in the surrounding mucosa. Other histopathological features of mucosal melanoma include frequent vascular infiltration and multicentricity[22,23]. Immunohistochemistry is the main tool used to differentiate melanoma from other tumors. Similar to methodologies used for cutaneous melanoma, MM differentially express S-100 proteins and melanocyte markers, including MART1/Melan-A, HMB-45, tyrosinase and MITF. Approximately half of MM patients carry BRAF mutations that provide loci for targeted therapies[24].

Clinical staging of mucosal melanoma is crucial for determining the extent of the disease and guiding treatment decisions. There are two staging methods for anorectal melanoma: (1) These methods were developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and are commonly used in clinical practice. This is a staging method based on the depth of the primary tumor; the lesion is confined to the mucosal layer, located in the submucosa, and infiltrates into the muscular layer. The deeper the lesion infiltration is, the greater the risk of lymph node metastasis; and (2) The other staging system is based on the spread of the disease only: localized disease only is described as stage I, regional lymph node disease as stage II and metastatic disease as stage III[25].

We collected eight chart reports of primary rectal mucosal melanoma during the last 6 years[26-32], most of which involved female patients; most of these patients were seen for rectal bleeding (62.5%), anal masses (37.5%), and discomfort or pain during defecation (25%). There was one case of distant metastasis, and the remaining cases were mostly confined to the bowel wall.

The mainstay of treatment for MM remains surgery. In the collected case reports, most patients without distant and lymph node metastases and peripheral spread were treated by LE[26-31]; when local and lymph node metastases were present, traditional abdominal perineal resection (APR) was still used[32]. Traditionally, the surgical treatment of rectal-anal melanoma has been APR because of the wide scope of surgical resection, removal of the anal sphincter and removal of the rectal mesenteric draining lymph nodes to reduce the recurrence rate. However, in recent decades, LE has been favored by many surgeons. Compared with APR, this technique maintains patient quality of life due to its ability to avoid colostomy, and there is no difference in the recurrence rate. Surgical resection is the best option for such patients, especially in the absence of local and lymph node metastases. The goal of surgical resection is to achieve negative margins. This goal may be influenced by tumor size, anatomical location, degree of functional preservation and patient wishes[33,34]. Although several studies have suggested that APR improves local recurrence rates compared to LE[35,36], other studies have not found a difference in local recurrence rates[37,38]. Therefore, APR is not recommended as a treatment for anal melanoma in the absence of any demonstrable survival benefit and when it is technically feasible.

In this case, EUS revealed that the lesions were located in the mucosa and submucosa and did not invade the muscle layer. Because the lesion was far from the anus, the patient underwent extensive LE and lymph node dissection to ensure good postoperative quality of life. No local lymph node metastasis was found on postoperative pathology, which indicated stage I disease. The patient received temozolomide combined with cisplatin adjuvant chemotherapy. There is currently no optimal follow-up strategy for patients with mucosal melanoma. A retrospective study that analyzed the recurrence patterns of localized melanoma showed recurrence rates of 40%, 34%, 33%, 18%, and 0% at 1, 2, 3, 5, and 10 years, respectively[39]. This finding is consistent with the recommended follow-up time for patients with cutaneous melanoma. Therefore, it is necessary to follow such patients for 5-10 years.

In summary, although the diagnosis of rectal mucosal melanoma remains difficult, EUS has a diagnostic role in identifying the depth of infiltration and provides a basis for surgical treatment modalities. Early diagnosis and appropriate management are necessary to improve the prognosis of rectal mucosal melanoma patients.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade C, Grade D

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Kaneko J, Japan; Oprea VD, Romania S-Editor: Zheng XM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Chan KK, Chan RC, Ho RS, Chan JY. Clinical Patterns of Melanoma in Asians: 11-Year Experience in a Tertiary Referral Center. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;77 Suppl 1:S6-S11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee HY, Chay WY, Tang MB, Chio MT, Tan SH. Melanoma: differences between Asian and Caucasian patients. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41:17-20. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gandini S, Autier P, Boniol M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;107:362-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thompson JF, Scolyer RA, Kefford RF. Cutaneous melanoma in the era of molecular profiling. Lancet. 2009;374:362-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yu J, Luo X, Huang H, Zhai Z, Shen Z, Lin H. Clinical Characteristics of Malignant Melanoma in Southwest China: A Single-Center Series of 82 Consecutive Cases and a Meta-Analysis of 958 Reported Cases. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim SY, Yun SJ. Cutaneous Melanoma in Asians. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chi Z, Li S, Sheng X, Si L, Cui C, Han M, Guo J. Clinical presentation, histology, and prognoses of malignant melanoma in ethnic Chinese: a study of 522 consecutive cases. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang N, Wang L, Zhu GN, Sun DJ, He H, Luan Q, Liu L, Hao F, Li CY, Gao TW. The association between trauma and melanoma in the Chinese population: a retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:597-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jung HJ, Kweon SS, Lee JB, Lee SC, Yun SJ. A clinicopathologic analysis of 177 acral melanomas in Koreans: relevance of spreading pattern and physical stress. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1281-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elder DE, Bastian BC, Cree IA, Massi D, Scolyer RA. The 2018 World Health Organization Classification of Cutaneous, Mucosal, and Uveal Melanoma: Detailed Analysis of 9 Distinct Subtypes Defined by Their Evolutionary Pathway. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2020;144:500-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Weber CO. Chirurgische Erfahrungen und Untersuchungen nebst zahlreichen Beobachtungen aus der chirurgischen Klinik und dem evangelischen Krankenhause zu Bonn. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter Incorporated, 1859: 304. |

| 12. | Wang X, Si L, Guo J. Treatment algorithm of metastatic mucosal melanoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2014;3:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhu H, Dong D, Li F, Liu D, Wang L, Fu J, Song L, Xu G. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic factors in patients with non-cutaneous malignant melanoma: a single-center retrospective study of 71 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1390-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cui CL, Li ZW, Lian B, Li SM, Tang BX, Chi ZH, Si L, Sheng XN, Mao LL, Guo J. [Clinical presentation, histology and prognosis of mucosal melanoma in ethnic Chinese: A study of 212 consecutive cases]. Linchuang Zhongliuxue Zazhi. 2012;17:626-633. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Sommer L. Generation of melanocytes from neural crest cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:411-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Goldgeier MH, Klein LE, Klein-Angerer S, Moellmann G, Nordlund JJ. The distribution of melanocytes in the leptomeninges of the human brain. J Invest Dermatol. 1984;82:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Patrick RJ, Fenske NA, Messina JL. Primary mucosal melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:828-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang S, Sun S, Liu X, Ge N, Wang G, Guo J, Liu W, Hu J. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastrointestinal melanoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:330-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sergi MC, Filoni E, Triggiano G, Cazzato G, Internò V, Porta C, Tucci M. Mucosal Melanoma: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25:1247-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Spencer KR, Mehnert JM. Mucosal Melanoma: Epidemiology, Biology and Treatment. Cancer Treat Res. 2016;167:295-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yde SS, Sjoegren P, Heje M, Stolle LB. Mucosal Melanoma: a Literature Review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Manolidis S, Donald PJ. Malignant mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: review of the literature and report of 14 patients. Cancer. 1997;80:1373-1386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Freedman HM, DeSanto LW, Devine KD, Weiland LH. Malignant melanoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol. 1973;97:322-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schadendorf D, Fisher DE, Garbe C, Gershenwald JE, Grob JJ, Halpern A, Herlyn M, Marchetti MA, McArthur G, Ribas A, Roesch A, Hauschild A. Melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 41.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 25. | Falch C, Stojadinovic A, Hann-von-Weyhern C, Protic M, Nissan A, Faries MB, Daumer M, Bilchik AJ, Itzhak A, Brücher BL. Anorectal malignant melanoma: extensive 45-year review and proposal for a novel staging classification. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:324-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kobakova I, Stoyanov G, Popov H, Spasova-Nyagulova S, Stefanova N, Stoev L, Yanulova N. Anorectal Melanoma - a Histopathological Case Report and a Review of the Literature. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2018;60:641-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Biswas J, Bethineedi LD, Dhali A, Miah J, Ray S, Dhali GK. Challenges in managing anorectal melanoma, a rare malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;105:108093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lian J, Xu A, Chu Y, Chen T, Xu M. Early primary anorectal malignant melanoma treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection: a case report. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:959-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | El Youssi Z, Mansouri H, Elouaouch S, Moukhlissi M, Berhili S, Mezouar L. Early-Stage Primary Rectal Melanoma: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15:e42629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Coyne JD, O'Byrne P. Malignant melanoma of the rectum presenting as cloacogenic polyp: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2020;102:e67-e69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Saadaat R, Saifullah, Adelyar MA, Rasool EE, Abdul-Ghafar J, Haidary AM. Primary malignant melanoma of rectum: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023;104:107942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yeung HM, Gupta B, Kamat B. A Rare Case of Primary Anorectal Melanoma and a Review of the Current Landscape of Therapy. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2020;10:371-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ascierto PA, Accorona R, Botti G, Farina D, Fossati P, Gatta G, Gogas H, Lombardi D, Maroldi R, Nicolai P, Ravanelli M, Vanella V. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;112:136-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jarrom D, Paleri V, Kerawala C, Roques T, Bhide S, Newman L, Winter SC. Mucosal melanoma of the upper airways tract mucosal melanoma: A systematic review with meta-analyses of treatment. Head Neck. 2017;39:819-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kottakota V, Warikoo V, Yadav AK, Salunke A, Jain A, Sharma M, Bhatt S, Puj K, Pandya S. Clinical and oncological outcomes of surgery in Anorectal melanoma in Asian population: A 15 year analysis at a tertiary cancer institute. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;28:100415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Temperley HC, O'Sullivan NJ, Keyes A, Kavanagh DO, Larkin JO, Mehigan BJ, McCormick PH, Kelly ME. Optimal surgical management strategy for treatment of primary anorectal malignant melanoma-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:3193-3200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Perez DR, Trakarnsanga A, Shia J, Nash GM, Temple LK, Paty PB, Guillem JG, Garcia-Aguilar J, Bello D, Ariyan C, Carvajal RD, Weiser MR. Locoregional lymphadenectomy in the surgical management of anorectal melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2339-2344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Smith HG, Glen J, Turnbull N, Peach H; Board R; Payne M, Gore M, Nugent K, Smith MJF. Less is more: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of radical versus conservative primary resection in anorectal melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;135:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wen X, Li D, Zhao J, Li J, Yang T, Ding Y, Peng R, Zhu B, Huang F, Zhang X. Time-varying pattern of recurrence risk for localized melanoma in China. World J Surg Oncol. 2020;18:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |