Published online Jun 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2773

Revised: February 8, 2024

Accepted: April 7, 2024

Published online: June 6, 2024

Processing time: 146 Days and 1.7 Hours

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication rates have fallen globally, likely in large part due to increasing antibiotic resistance to traditional therapy. In areas of high clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance such as ours, Maastricht VI guidelines suggest high dose amoxicillin dual therapy (HDADT) can be considered, subject to evidence for local efficacy. In this study we assess efficacy of HDADT therapy for H. pylori eradication in an Irish cohort.

To assess the efficacy of HDADT therapy for H. pylori eradication in an Irish cohort as both first line, and subsequent therapy for patients diagnosed with H. pylori.

All patients testing positive for H. pylori in a tertiary centre were treated pro

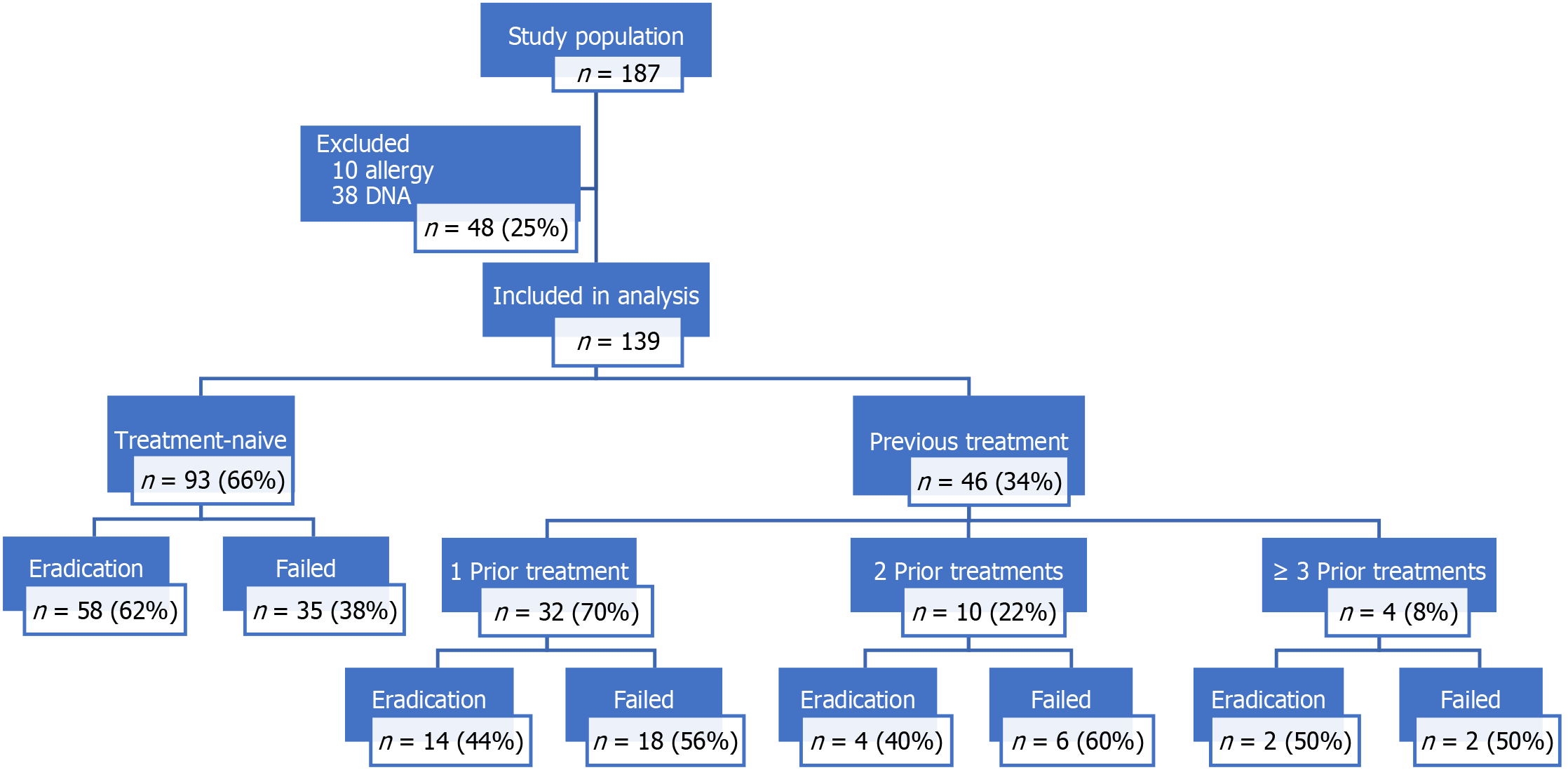

One hundred and ninety-eight patients were identified with H. pylori infection, 10 patients were excluded due to penicillin allergy and 38 patients refused follow up testing. In all 139 were included in the analysis, 55% (n = 76) were female, mean age was 46.6 years. Overall, 93 (67%) of patients were treatment-naïve and 46 (33%) had received at least one previous course of treatment. The groups were statistically similar. Self-reported compliance with HDADT was 97%, mild side-effects occurred in 7%. There were no serious adverse drug reactions. Overall the eradication rate for our cohort was 56% (78/139). Eradication rates were worse for those with previous treatment [43% (20/46) vs 62% (58/93), P = 0.0458, odds ratio = 2.15]. Age and Gender had no effect on eradication status.

Overall eradication rates with HDADT were disappointing. Despite being a simple and possibly better tolerated regime, these results do not support its routine use in a high dual resistance country. Further investigation of other regimens to achieve the > 90% eradication target is needed.

Core Tip: We present a prospective assessment of high dose amoxicillin dual therapy (HDADT) for Helicobacter pylori in an Irish cohort. Ireland is a 'high dual-resistance country'-(clarithromycin and metronidazole)-mainstays of traditional treatment. Where bismuth-based therapy is unavailable, as in Ireland, European guidelines recommend HDADT can be considered. This is the first data on HDADT to date in Ireland, and despite promising data from Asia, European data remains scant. Our results show disappointing eradication rates; we discuss possible reasons why and provide clinical evidence to authorities for the need to make bismuth-therapy available in our country. We advise against HDADT in European populations.

- Citation: Costigan C, O'Sullivan AM, O'Connell J, Sengupta S, Butler T, Molloy S, O'Hara FJ, Ryan B, Breslin N, O'Donnell S, O'Connor A, Smith S, McNamara D. Helicobacter pylori: High dose amoxicillin does not improve primary or secondary eradication rates in an Irish cohort. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(16): 2773-2779

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i16/2773.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2773

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a recognised cause of chronic gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, mucosal associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and other gastric cancers[1,2]. In 1994 it was recognised by the World Health Organization as a class 1 carcinogen[3] and in 2015 the Kyoto consensus classified it as an infectious disease, recommending eradication therapy in all diagnosed cases[4].

Although antimicrobial guidelines vary worldwide, since 1997 European guidelines have relied on ‘triple therapy’ consisting of amoxicillin, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and either clarithromycin or metronidazole for eradication, which has caused an increase in the prevalence of resistance to these agents, and a corresponding decrease in the successful eradication rates in many European countries[5-7]. In areas designated as ‘high resistance countries’ it is imperative we investigate new antimicrobial regimens to achieve the > 90% eradication target which is recommended[8]. Ireland currently is classified as an area of high dual resistance, that is clarithromycin resistance > 15% and metronidazole resistance > 15%[9].

Recently the European Helicobacter pylori Study Group and Consensus Panel have published the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report on the treatment of H. pylori at a European level and have recommended that in areas of high clarithromycin resistance (> 15%) empiric treatment with bismuth quadruple therapy (BQT) or levofloxacin quadruple therapy may be used. Bismuth is not widely available in Ireland, while combination tablets are also unavailable, and as such the adoption of Bismuth based quadruple therapy among clinicians has been poor. Similarly, concerns regarding the potential adverse events of fluroquinolones and national guidance restricting their used has also limited the uptake of Levofloxacin-based regimens[10,11].

In these circumstances, high dose amoxicillin dual therapy (HDADT) or rifabutin triple therapy may be trialed, subject to local evidence of efficacy[12]. HDADT has been advocated as possible second line or rescue treatment in other jurisdictions with reasonable eradication success reported[13].

While evidence is lacking currently for HDADT as a first line treatment in Europe, several studies in Asian populations have demonstrated promise[14-17]. In theory, HDADT as a primary treatment would make sense as reported resistance rates to amoxicillin in Naïve patients are low, its use would represent good antibiotic stewardship, and it would also represent a simpler regimen which may impact patient compliance.

We aimed to prospectively assess the efficacy of HDADT therapy for H. pylori eradication in an Irish cohort.

This was a prospective open label study performed in a tertiary referral centre in Ireland. After approval by our institution as a quality improvement initiative, all adult patients > 18 years of age diagnosed with H. pylori via urea breath test (UBT) or upper endoscopy were sequentially enrolled. Exclusion criteria included: Known or suspected Penicillin allergy, refusal to consent or refusal to attend for Post-Eradication UBT.

All patients were prescribed a 14-d course of HDADT consisting of amoxicillin (1 g tid) and esomeprazole (40 mg bid). At the end of the study compliance to therapy and side effects were assessed by phone interview. At least 4 wk after the cessation of antimicrobial therapy a post-eradication a 13C UBT was performed using our standard protocol with × 50 mg Urea (Diabact, Laboratoires Mayoly Spindler, France) to evaluate H. pylori status. All patients were advised to avoid PPI for 7 d, antibiotics for 28 d, and to fast for 6 h prior to attending for their breath test. A delta-over-baseline > 4% was considered positive.

Patient demographics and prior medical histories were recorded from their electronic patient record. H. pylori testing data and eradication rates were accessed from the GI lab database. The effects of demographic data on eradication rates were analysed via Fisher Exact test, logistical regression or χ2 where appropriate.

One hundred and eighty-seven patients were identified with H. pylori infection over the 8 months timeframe of the study. Of these, 10 patients were excluded due to penicillin allergy and 38 patients refused follow up testing. Of the 139 patients included in the analysis, 55% (n = 76) were female, the mean age was 46.6 years (SD: ± 15.9, range: 19-83 years). In all 93 (67%) patients received HDADT as their first-line therapy, while 46 (33%) received HDADT after at least one course of alternative treatment. All patients were receiving empirical therapy, none had undergone antibiotic resistance testing prior to treatment. Demographics were similar among naïve and prior treatment groups. Overall only 78 (56%) were UBT negative post HDADT treatment (Figure 1).

Eradication rates were statistically worse for those with previous treatment [43% (20/46) vs 62% (58/93), P = 0.02], odds ratio = 2.2 (95%CI: 1.1090-4.7074) (Table 1).

| Post treatment UBT result | First line therapy group | Prior therapy group | Total |

| Negative | 58 | 20 | 78 |

| Positive | 35 | 26 | 61a |

| Total | 93 | 46 | 139 |

Of note, all patients in the ‘previous treatment’ group had been exposed to treatment regimens including amoxicillin.

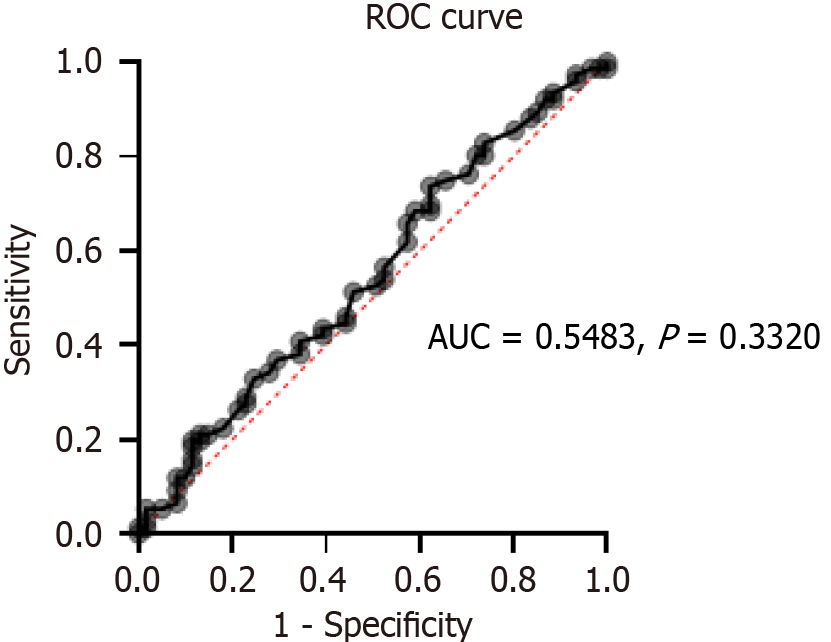

There was no statistically significant difference in eradication rates by gender (P = 0.8648) (Table 2), or age (by logistical regression, AUC = 0.5483, P = 0.3320) (Figure 2).

| Post treatment UBT | Negative | Positive | Total |

| Female | 42 | 34 | 76 |

| Male | 36 | 27 | 63a |

| Total | 78 | 61 | 139 |

In the previous treatment cohort, n = 46, 32 (70%) had previously had a single therapy with clarithromycin based triple therapy for 14 d, 10 patient (22%) had had two therapies, and 4 (9%) were receiving rescue therapies.

Eradication rates in the previous treatment cohort ranged from 44 to 100%, but the sample size for each regiment was too small to support further meaningful statistical analysis (Table 3).

| Total | % of total | Eradication | Eradication (%) | |

| CTT | 32 | 70 | 14 | 44 |

| CTT, LTT | 5 | 11 | 4 | 80 |

| CTT, MTT | 4 | 9 | 2 | 50 |

| CTT, MTT, LTT | 3 | 6 | 1 | 33 |

| CTT, BQT | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| CTT, LTT, BQT | 1 | 2 | 1 | 100 |

Overall, side effects occurred in 10 (7%) patients. Nausea was recorded in all 10 cases, with diarrhoea additionally reported in 3 (2%). There were no serious adverse drug reactions. Self-reported compliance with the regimen was (134/139) 97%, however it should be noted that all patients who did not complete the full regimen had successful H. pylori eradication.

Overall eradication rates were disappointingly low in our prospective single centre open label study of HDADT in an area of high dual clarithromycin and metronidazole resistance. Although patients undergoing first-line therapy were statistically more likely to have successful eradication (62% vs 43%, P = 0.0457), this rate remains far below the target of > 90% successful eradication.

From a cost, antibiotic stewardship and medication compliance perspectives, HDADT could be considered as a viable first line therapy for H. pylori when BQT or other alternatives are unavailable, but our study suggests its efficacy is too low to recommend. Rather, our study further enhances the move towards rapid antibiotic sensitivity testing by either polymerase chain reaction for genes known to be associated with antimicrobial resistance or E-Tests, with clarithromycin triple therapy the preferred option in proven sensitive patients, and bismuth or levofloxacin quadruple preferred in those not sensitive to clarithromycin.

Our study has several limitations. There is potential bias as an open label trial, however it was designed as such as a pilot assessment of a novel treatment, had there been evidence of efficacy a formal randomised controlled trial may have been of value. In addition, the relatively small population size may be an issue, although in our cohort, this represents the growing reality whereby H. pylori infection is infrequently diagnosed even in symptomatic patients presenting to our gastroenterology service. As such any future audit to assess treatment success based on international guidance is going to be performed in a similar cohort. The findings from this study therefore truly reflect our patient population and are therefore relevant to our, and other practices, who care for a similar demographic. Despite the small sample size, as expected we did find a treatment advantage for first line over subsequent treatment courses (odds ratio = -2.5). Of note also is the large number of participants who did not attend for post-eradication testing. 38 patients-representing 19% of those diagnosed in the time frame did not attend, likely representing a re-testing bias towards those with ongoing symptoms and persistent infection. It may the case in the future that the possibility of community-based or at-home testing will improve attendance for post-eradication testing, but currently this is an unfortunate reality of healthcare in Ireland.

Our study is similar to recent data from the European Registry on Helicobacter pylori management which failed to demonstrate that HDADT is effective in a European population of 62 patients[18]. This is in contrast with many larger studies and metanalyses from Asia[14-17]. One explanation for this may be due to the background of amoxicillin usage in our populations. Amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (co-amoxiclav) represents first line antibiotic therapy for many common infections in Ireland, and so prior exposure to sub-therapeutic doses of this this antibiotic over time may have cultivated resistance in sections of our population.

Also, some of the differences in experience with HDADT eradication rates globally may be due in part to different medication regimens: Some studies suggest that administering 750 mg of amoxicillin four times a day is superior to administering 1 g three times a day[16,17]. This likely related to maintaining a therapeutic drug level throughout the day. Local variations in the rates of drug metabolization, and factors which affect this such as concurrent dietary, alcohol or medication intake may have an effect, as well as the average height and weight of participants in different studies around the world, as these drugs are not dose-adjusted. Other studies have postulated that the difference in common P450 CYP2C19 polymorphisms between European and Asian populations may also influence the differences in HDADT eradication rates, as higher variations in gastric pH levels have been shown to adversely impact on amoxicillin’s bactericidal effects[19-21]. In the future, as personalised medicine and access to genotyping becomes more cost-effective and widespread, screening for patients carrying variant alleles may allow for personalised dosing of PPIs. The more recent development of a new class of drugs; potassium-competitive acid blockers (e.g., vonoprazan) have also shown promise in maintaining lower gastric pH levels and have shown even more promise, again mostly in Asian populations, as part of H. pylori eradication therapy when compared with standard PPI therapy, however these medications have yet to be approved by the European Medicines Agency[22,23].

While the exact causes are not clear, whatever the rational, HDADT eradication rates reported in Asia are different from the European experience, and it cannot be considered a viable first- or second-line treatment in this part of the world.

HDADT has insufficient eradication rates to recommend it as first line or second-line therapy in high dual resistance European populations. Further studies into novel regimens are required.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Irish Society of Gastroenterology.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Ireland

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

P-Reviewer: Huang YQ, China; Wang XY, China S-Editor: Zheng XM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Ridola L, Repici A, Manta R, Andriani A. Gastric MALT lymphoma: old and new insights. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:27-33. [PubMed] |

| 3. | World Health Organization. International Agency For Research On Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 60. Lyon: IARC, 1994: 1-241. |

| 4. | Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P; faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353-1367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1322] [Cited by in RCA: 1173] [Article Influence: 117.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 679] [Cited by in RCA: 674] [Article Influence: 24.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Megraud F, Coenen S, Versporten A, Kist M, Lopez-Brea M, Hirschl AM, Andersen LP, Goossens H, Glupczynski Y; Study Group participants. Helicobacter pylori resistance to antibiotics in Europe and its relationship to antibiotic consumption. Gut. 2013;62:34-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:719-31.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 320] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O'connor A, Taneike I, Nami A, Fitzgerald N, Murphy P, Ryan B, O'connor H, Qasim A, Breslin N, O'moráin C. Helicobacter pylori resistance to metronidazole and clarithromycin in Ireland. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1123-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coloma PM, de Ridder M, Bezemer I, Herings RM, Gini R, Pecchioli S, Scotti L, Rijnbeek P, Mosseveld M, van der Lei J, Trifirò G, Sturkenboom M; EU-ADR Consortium. Risk of cardiac valvulopathy with use of bisphosphonates: a population-based, multi-country case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1857-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | HPRA Drug Safety Newsletter. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics - EU review advises restrictions for certain infections and warns of rare but serious long lasting adverse reactions. 91st ed. 2018. Available from: https://www.hpra.ie/docs/default-source/publications-forms/newsletters/hpra-drug-safety-newsletter-edition-91.pdf?sfvrsn=7. |

| 12. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1349] [Article Influence: 74.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 1014] [Article Influence: 126.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Huang Q, Shi Z, Cheng H, Ye H, Zhang X. Efficacy and Safety of Modified Dual Therapy as the First-line Regimen for the Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:856-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yang JC, Lin CJ, Wang HL, Chen JD, Kao JY, Shun CT, Lu CW, Lin BR, Shieh MJ, Chang MC, Chang YT, Wei SC, Lin LC, Yeh WC, Kuo JS, Tung CC, Leong YL, Wang TH, Wong JM. High-dose dual therapy is superior to standard first-line or rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:895-905.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhu YJ, Zhang Y, Wang TY, Zhao JT, Zhao Z, Zhu JR, Lan CH. High dose PPI-amoxicillin dual therapy for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820937115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Li C, Shi Y, Suo B, Tian X, Zhou L, Song Z. PPI-amoxicillin dual therapy four times daily is superior to guidelines recommended regimens in the Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy within Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fernández-Salazar L, Campillo A, Rodrigo L, Pérez-Aisa Á, González-Santiago JM, Segarra Ortega X, Denkovski M, Brglez Jurecic N, Bujanda L, Gómez Rodríguez BJ, Ortuño J, Georgopoulos S, Jonaitis L, Puig I, Nyssen OP, Megraud F, O'Morain C, Gisbert JP. Effectiveness and Safety of High-Dose Dual Therapy: Results of the European Registry on the Management of Helicobacterpylori Infection (Hp-EuReg). J Clin Med. 2022;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lou HY, Chang CC, Sheu MT, Chen YC, Ho HO. Optimal dose regimens of esomeprazole for gastric acid suppression with minimal influence of the CYP2C19 polymorphism. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:55-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marcus EA, Inatomi N, Nagami GT, Sachs G, Scott DR. The effects of varying acidity on Helicobacter pylori growth and the bactericidal efficacy of ampicillin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:972-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hunfeld NG, Touw DJ, Mathot RA, Mulder PG, VAN Schaik RH, Kuipers EJ, Kooiman JC, Geus WP. A comparison of the acid-inhibitory effects of esomeprazole and pantoprazole in relation to pharmacokinetics and CYP2C19 polymorphism. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:150-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Huang J, Lin Y. Vonoprazan on the Eradication of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chey WD, Mégraud F, Laine L, López LJ, Hunt BJ, Howden CW. Vonoprazan Triple and Dual Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized Clinical Trial. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:608-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 56.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |