Published online Jun 6, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2738

Revised: April 8, 2024

Accepted: April 16, 2024

Published online: June 6, 2024

Processing time: 137 Days and 23.6 Hours

Complex and high-risk surgical complications pose pressing challenges in the clinical implementation and advancement of endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR). Successful perforation repair under endoscopy, thereby avoiding surgical intervention and postoperative complications such as peritonitis, are pivotal for effective EFTR.

To investigate the effectiveness and safety of EFTR assisted by distal serosal inversion under floss traction in gastric submucosal tumors.

A retrospective analysis of patients with gastric and duodenal submucosal tumors treated with EFTR assisted by the distal serosa inversion under dental floss traction from January 2023 to January 2024 was conducted. The total operation time, tumor dissection time, wound closure time, intraoperative bleeding volume, length of hospital stay and incidence of complications were analyzed.

There were 93 patients, aged 55.1 ± 12.1 years. Complete tumor resection was achieved in all cases, resulting in a 100% success rate. The average total operation time was 67.4 ± 27.0 min, with tumor dissection taking 43.6 ± 20.4 min. Wound closure times varied, with gastric body closure time of 24.5 ± 14.1 min and gastric fundus closure time of 16.6 ± 8.7 min, showing a significant difference (P < 0.05). Intraoperative blood loss was 2.3 ± 4.0 mL, and average length of hospital stay was 5.7 ± 1.9 d. There was no secondary perforation after suturing in all cases. The incidence of delayed bleeding was 2.2%, and the incidence of abdominal infection was 3.2%. No patient required other surgical intervention during and after the operation.

Distal serosal inversion under dental-floss-assisted EFTR significantly reduced wound closure time and intraoperative blood loss, making it a viable approach for gastric submucosal tumors.

Core Tip: In a comprehensive study of 93 patients diagnosed with gastric and duodenal submucosal tumors, who underwent endoscopic full-thickness resection facilitated by distal serosa inversion under dental floss traction, we observed a significant reduction in wound closure time and intraoperative bleeding volume. This approach demonstrated feasibility and has potential for wider application and adoption due to its demonstrated benefits.

- Citation: Liu TW, Lin XF, Wen ST, Xu JY, Fu ZL, Qin SM. Effect of endoscopic full-thickness resection assisted by distal serosal turnover with floss traction for gastric submucosal masses. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(16): 2738-2744

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i16/2738.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i16.2738

A submucosal tumor in the digestive tract is an elevated lesion that originates from the layers beneath the mucosal layer, primarily involving the muscularis mucosa, submucosa and muscularis propria[1]. Endoscopic resection has become the preferred treatment for various submucosal tumors because of its benefits such as less trauma, quick recovery, low complication rate and low cost[2,3]. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) can completely remove gastrointestinal tumors and minimize the risk of residual tumor. In comparison to laparoscopic techniques that involve damaging the abdominal wall and surrounding structures of the digestive tract, EFTR is significantly less traumatic and demonstrates notable clinical efficacy[4].

Complex surgical procedures and high-risk surgical complications pose pressing challenges in the clinical im

A database search was conducted to identify patients who underwent EFTR for gastric and duodenal submucosal tumors using EFTR assisted by distal serosal inversion under floss traction at the Endoscopy Center of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine from January 2023 to January 2024. The preoperative diagnosis was in accordance with the applicable criteria of EFTR, that is, preoperative endoscopic ultrasonography suggested that the lesion originated from the muscularis propria and computed tomography (CT) revealed that the tumor protruded into the subserosa or was partially extraluminal. This encompassed cases of gastric submucosal tumors tightly adhered to the serosa, resistant to other endoscopic treatments. The general clinical data, lesion location, lesion size, lesion invasion depth, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, and incidence of surgical complications were recorded in detail.

The surgical procedures were facilitated by utilizing advanced equipment including the Olympus GIF-Q260J electronic endoscope, KD650-Q Dual knife, KD-610LIT knife, KD-620LRHook knife, FD-410LR thermal biopsy forceps, NM24L21 injection needle, ERBE VIO 200s + APC2 high-frequency electric cutting device, argon ion coagulator, SP-210U-25 electric snare, and ROCC-D-26-195 metal clip, along with auxiliary tools such as dental floss. A transparent cap was required to be attached to the distal end of the inner lens during the procedure.

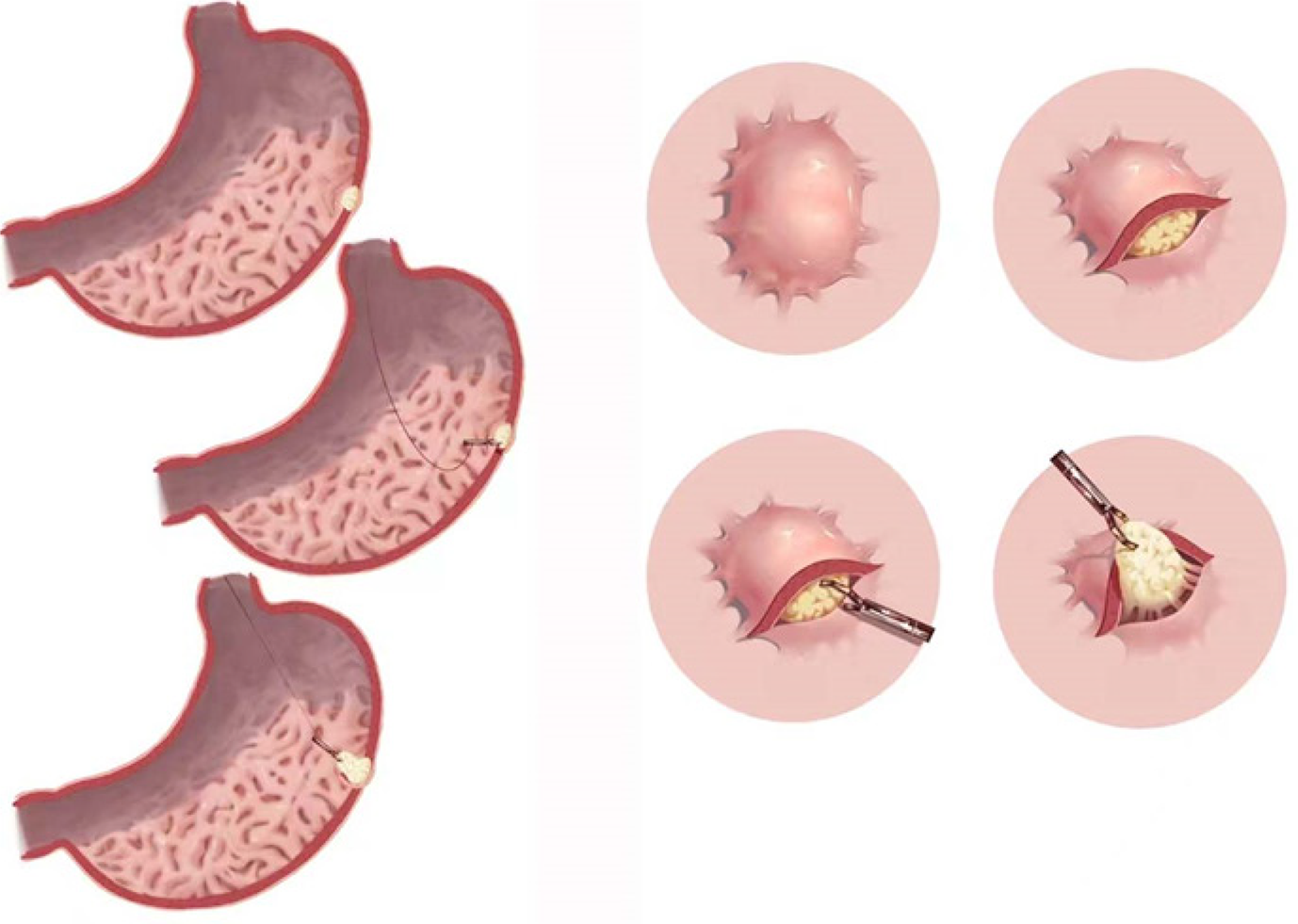

Preoperative blood routine, coagulation, electrocardiogram and chest and upper abdominal CT examinations were completed. All patients underwent EFTR under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation assistance, and the following procedures were used: (1) Marking: We observed and located the lesion after inserting the endoscope, and used a needle knife or argon ion coagulation to perform electrocoagulation marking at the edge of the lesion away from 0.5-1 cm; (2) Submucosal injection: A mixture of sodium hyaluronate, glycerol fructose, epinephrine, and indigo carmine was submucosally injected around the tumor to elevate the lesional mucosa; (3) Incision: The mucosal layer was incised from the outer edge from the distal end of the lesion with a disposable mucosal incision knife; (4) Exfoliating and excision: We performed submucosal exfoliating, located the tumor, exfoliated along the tumor, and treated the exposed blood vessels and bleeding with thermal coagulation forceps; (5) Serosal inversion under dental floss traction: When there was a small perforation after full-thickness incision during tumor removal, titanium clips and dental floss traction were used to invert the tumor from the distal end of the perforation, ensuring the serosal surface faced the endoscope; and (6) Wound treatment after dissection: In the state of serosal inversion, heat coagulation forceps were used to treat the exposed blood vessels on the serosal surface, and full-thickness excision was performed. After rinsing the wound, the wound was closed and sutured intensively with harmonious clips, and the lesion specimens were collected and sent for examination.

Following surgery, patients were advised to remain in a supine position, undergo 24-h fasting, and receive acid suppression, anti-infective treatment, and routine fluid rehydration therapy. They were closely monitored for physical signs, gas passage and bowel movements. If no complications such as gastrointestinal perforation, irritation, infection, or delayed bleeding occurred, patients were allowed water intake on postoperative day 2 and transitioned to a liquid diet for 1 wk. Subsequent follow-up examinations using gastroscopy or ultrasound gastroscopy were scheduled at 3 and 6 months postoperatively to assess wound healing progress, detect any local residual lesions, and monitor lesion recurrence.

General information of surgical patients was collected, including lesion site, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative pathological type, postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay. The size of the lesion was calculated according to the long diameter of the lesion. In addition, the complete operation time, tumor dissection time and wound closure time were calculated. The complete operation time was calculated as the duration from suture completion to the application of the transparent cap. Tumor dissection time was defined as the time taken for tumor removal minus the transparent cap application time. Wound closure time was calculated as the time of suture completion minus the tumor removal time.

The data were analyzed using Excel and SPSS 20.0. Measurement data such as age, lesion size, operation time and intraoperative blood loss were described as mean ± SD. Distributions were compared using an independent sample t test. Categorical data such as gender, efficacy, adverse reactions, and complications were described by frequency (n) and rate (%).

A total of 93 patients were included, including 62 females and 31 males, ranging in age from 22 to 77 years, with an average of 55.1 ± 12.1 years. The tumor was completely resected in all patients.

The lesions were located in the fundus, body, fundus-corpus junction, or duodenum. Specifically, 69 cases exhibited lesions in the fundus of the stomach, with 33 cases in the fornix, 18 on the posterior wall, 17 cases on the anterior wall, and one on the lesser curvature. Additionally, 20 cases showed lesions in the gastric body, with nine cases on the anterior wall, seven on the posterior wall, one on the greater curvature, and three on the lesser curvature. Three cases presented lesions at the fundus-corpus junction. One case had a lesion at the descending duodenal junction. The size of the lesions ranged from 5 to 30 mm, with an average of 8.8 ± 4.7 mm. The postoperative pathological types included stromal tumor in 66 cases, leiomyoma in 21, schwannoma in two, ectopic pancreas in two, spindle cell lesion in one, and fibrous tumor in one.

The total operation time across all cases ranged from 19 to 180 min, with an average of 67.4 ± 27.0 min, while the tumor dissection time varied from 13 to 125 min, with an average of 43.6 ± 20.4 min. Wound closure time ranged from 4 to 59 min, with an average of 18.2 ± 10.5 min. The cases at the junction of the fundus-corpus and the junction of the descending duodenal bulb were classified as other parts, and the operation time of different lesions was compared. The operation time for lesions in the gastric fundus averaged 65.6 ± 24.5 min, whereas for lesions in the gastric corpus, it was 78.2 ± 33.5 min. Although the operation time for gastric corpus lesions exceeded that of gastric fundus lesions, the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). The operation time for lesions in other areas was 44.0 ± 10.6 min, which was significantly shorter than that for the fundus and corpus (P < 0.05). The tumor dissection time was 48.0 ± 24.6 min for gastric corpus lesions, 43.1 ± 19.2 min for gastric fundus lesions, and 29.5 ± 8.4 min for other locations, with no significant differences observed between the groups. Suture time for the gastric corpus averaged 24.5 ± 14.1 min, and 16.6 ± 8.7 min for the gastric fundus, which was a significant difference (P < 0.05). The suture time for other sites was 13.0 ± 5.6 min, showing no significant difference compared to the suture times for the gastric corpus and fundus (Table 1).

| Lesions | Cases | Operation time (min) | Stripping time (min) | Suture time (min) | Lesion size (mm) | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Hospital stay (d) |

| Gastric body | 20 | 78.2 ± 33.5 | 48.0 ± 24.6 | 24.5 ± 14.1a | 9.2 ± 3.9 | 3.7 ± 6.6 | 5.8 ± 1.7 |

| Front wall | 9 | 76.1 ± 36.4 | 43.1 ± 22.7 | 26.6 ± 16.6 | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 2.9 | 6.1 ± 1.9 |

| Back wall | 7 | 83.7 ± 38.3 | 58.1 ± 31.2 | 22.7 ± 12.8 | 9.4 ± 4.4 | 6.0 ± 10.8 | 5.4 ± 1.5 |

| Small bend | 3 | 84.0 ± 5.6 | 40.3 ± 14.5 | 25.3 ± 15.2 | 12.7 ± 7.0 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 2.0 |

| Big bend | 1 | 59 | 43 | 16 | 8 | 1 | 7 |

| Fundus | 69 | 65.6 ± 24.5 | 43.1 ± 19.2 | 16.6 ± 8.7c | 8.8 ± 5.0 | 2.1 ± 2.9 | 5.7 ± 1.7 |

| Dome | 33 | 61.3 ± 23.8 | 40.9 ± 17.6 | 14.9 ± 7.6 | 8.5 ± 4.7 | 2.3 ± 3.5 | 5.7 ± 2.0 |

| Front wall | 17 | 65.6 ± 25.5 | 40.6 ± 13.5 | 16.3 ± 8.3 | 8.7 ± 5.9 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 5.3 ± 1.4 |

| Back wall | 18 | 71.1 ± 23.0 | 45.8 ± 22.5 | 19.8 ± 10.4 | 9.3 ± 5.1 | 1.8 ± 2.6 | 5.9 ± 1.6 |

| Small bend | 1 | 111 | 96 | 15 | 8 | 2 | 6 |

| Others | 4 | 44.0 ± 10.6a,c | 29.5 ± 8.4 | 13.0 ± 5.6 | 7.8 ± 1.3 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 7.0 ± 4.2 |

| Total | 93 | 67.4 ± 27.0 | 43.6 ± 20.4 | 18.2 ± 10.5 | 8.8 ± 4.7 | 2.3 ± 4.0 | 5.7 ± 1.9 |

Intraoperative blood loss among the 93 patients ranged from 0 to 30 mL, with an average of 2.3 ± 4.0 mL, which was effectively managed using endoscopic argon ion coagulation and metal clips. The blood loss during surgery was 3.7 ± 6.6 mL for lesions in the gastric corpus, 2.1 ± 2.9 mL for those in the fundus, and 0.8 ± 0.5 mL for lesions in other locations, with no significant differences observed among the groups. The length of hospitalization ranged from 3 to 13 d, with an average of 5.7 ± 1.9 d. Patients with lesions in the gastric corpus had an average hospital stay of 5.8 ± 1.7 d; those with lesions in the gastric fundus stayed for 5.7 ± 1.7 d; and those with lesions in other areas stayed for 7.0 ± 4.2 d, with no significant differences among the groups.

All 93 patients experienced active perforation during the operation, with no instances of secondary perforation after wound closure. Delayed hemorrhage occurred in two cases on postoperative days 3 and 4, respectively, with a blood loss of 30 mL. Both cases underwent successful hemostasis through endoscopic argon ion coagulation and metal clip refixation, resulting in a delayed bleeding incidence of 2.2%. Three patients developed postoperative fever, indicative of potential intra-abdominal infection, which showed improvement following antibiotic treatment, resulting in an abdominal infection incidence of 3.2%. No patient required other surgical intervention during or after the operation.

EFTR has emerged as the preferred treatment for specific submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria or involving tight, inseparable adhesions between the tumor and the serosa. This procedure can be performed using either an exposed or a nonexposed approach. Exposed EFTR involves a free-hand endoscopic technique for tumor resection, where full-thickness excision is carried out before closing the wall defect. The primary advantage of exposed EFTR is its capability to achieve en bloc resection of regardless of tumor size. However, complications such as perforation and wall defects are common after EFTR, often resulting in issues such as intraoperative bleeding or infection of intra-abdominal[7]. Following exposed EFTR, the incidence of localized peritonitis was 9%[8], with an overall complication rate of 12.1%, of which, 11.7% necessitated additional surgical intervention[9]. Current challenges in performing exposed EFTR primarily include: (1) Difficulty in anatomical identification and hierarchic determination due to bleeding from lesions originating in the muscularis propria or serosal layer, complicating intraoperative visualization; (2) Poor exposure of the intraoperative visual field after full-thickness incision, particularly inadequate visualization of blood vessels in the serosal layer of the abdominal cavity, leading to delays in bleeding management; and (3) Challenges in proceeding with the operation after full-thickness incision as the lesion tends to protrude into the abdominal cavity[10].

In this study, the distal serosal inversion technique with dental flossing was used to assist exposed EFTR in the excision and treatment of intragastric submucosal tumors, which could solve the problems of poor serosal blood vessels and prolapse of the lesions into the abdominal cavity. The main features included the following: (1) When a small perforation occurred after full-thickness incision, caused by peeling off the tumor, the tumor was reversed after pulling with titanium clips and dental floss from the distal end of the perforation, so that the serosa faced the endoscope. In the state of serosal inversion, the exposed blood vessels on the serosal surface were treated with thermal coagulation forceps first, and then full-thickness resection was performed; and (2) Following complete excision of the tumor, the exposed blood vessels were electrocoagulated using thermal coagulation forceps. After the wound was washed, the metal clips were used to close and suture intensively from the serosal surface under traction (Figure 1). The advantage of this kind of traction is that it can fully expose the free-end blood vessels on the serosal surface to ensure that the operator can stop the bleeding and handle the blood vessels with a sufficient field of view. In addition, when the wound is repaired, the free serosal surface at the lower end can be fully exposed and sutured to reduce the suture time. This study retrospectively analyzed 93 cases of gastric and duodenal submucosal tumors treated using the distal serosal inversion technique with dental flossing to assist EFTR. The complete tumor resection rate was 100%, the mean operation time was 67.4 ± 27.0 min, the mean time of tumor dissection was 43.6 ± 20.4 min, and the mean hospital stay was 5.7 ± 1.9 d.

In this study, the tumor dissection time was approximately 13 min shorter than that reported by Tong et al[11]. Simultaneously, none of the 93 patients in this study experienced delayed perforation, and there were no instances of surgical transfer during or after the procedure. The occurrence rates of delayed bleeding and intra-abdominal infection were 2.2% and 3.2%, respectively, both lower than the reported complications associated with exposed EFTR[8] and comparable to those of unexposed EFTR[12]. The complete tumor resection rate and average hospital stay were similar to previous studies reporting EFTR of submucosal tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract[13]. This study was the first analysis and documentation of wound closure time (18.2 ± 10.5 min) and intraoperative blood loss (2.3 ± 4.0 mL) during EFTR utilizing the distal serosal inversion technique with dental floss traction. These parameters serve as indicators of visual field exposure and wound repair efficiency during endoscopy, offering valuable insights for future research in this domain. Endoscopic treatment and wound repair at the gastric fundus were previously considered to be more challenging due to the need for extreme reverse endoscopic manipulation[14]. This study compared tumor treatment indicators in different anatomical regions and revealed that the suturing time following EFTR treatment (16.6 ± 8.7 min) for fundal tumors using the distal serosal inversion with dental floss was significantly shorter than that for gastric corpus tumors. Operations in the gastric fundus showed reduced overall duration, tumor dissection time, wound closure time, intraoperative blood loss, and hospitalization compared to those in the gastric corpus. The findings suggest that EFTR assisted by the distal serosal inversion under dental floss traction can alleviate the challenges posed by endoscopic inversion in the gastric fundus. This approach enhances the operative field of view, minimizes visual blind spots, and boosts operational efficiency.

EFTR assisted with distal serosal turnover under dental floss traction can solve the problem of poor serosal vascular visibility. It can fully expose the free serosal surface at the distal end of the perforation, thereby reducing the time of tumor stripping and suturing of the wound surface, and lead to fewer postoperative complications, with better clinical efficacy and safety.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Martino A, Italy S-Editor: Zheng XM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao S

| 1. | Nishida T, Kawai N, Yamaguchi S, Nishida Y. Submucosal tumors: comprehensive guide for the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal submucosal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:479-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Standards of Practice Committee; Faulx AL, Kothari S, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Shaukat A, Qumseya BJ, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in subepithelial lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1117-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang C, Gao Z, Shen K, Cao J, Shen Z, Jiang K, Wang S, Ye Y. Safety and efficiency of endoscopic resection versus laparoscopic resection in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:667-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu S, Zhou X, Yao Y, Shi K, Yu M, Ji F. Resection of the gastric submucosal tumor (G-SMT) originating from the muscularis propria layer: comparison of efficacy, patients' tolerability, and clinical outcomes between endoscopic full-thickness resection and surgical resection. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:4053-4064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kaan HL, Ho KY. Endoscopic Full Thickness Resection for Gastrointestinal Tumors - Challenges and Solutions. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:541-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ge PS, Aihara H. Advanced Endoscopic Resection Techniques: Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection and Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:1521-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | D'Souza LS, Yang D, Diehl D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection for the Management of Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Lesions: Commentary. Gastroenterology. 2024;166:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lu J, Jiao T, Li Y, Zheng M, Lu X. Facilitating retroflexed endoscopic full-thickness resection through loop-mediated or rope-mediated countertraction (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:223-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ye LP, Zhang Y, Luo DH, Mao XL, Zheng HH, Zhou XB, Zhu LH. Safety of Endoscopic Resection for Upper Gastrointestinal Subepithelial Tumors Originating from the Muscularis Propria Layer: An Analysis of 733 Tumors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:788-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gu L, Wu Y, Yi J, Liu XW. [Current status and research advances on the use of assisted traction technique in endoscopic full-thickness resection]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;24:1122-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tong J, Zhou L, Luo ZL, Deng L. [Evaluation of the Effect of Endoscopic Full-Thickness Resection in the Treatment of Extraluminal Gastric Stromal Tumors]. Zhongliu Yufang Yu Zhiliao. 2022;35:255-261. |

| 12. | Schmidt A, Beyna T, Schumacher B, Meining A, Richter-Schrag HJ, Messmann H, Neuhaus H, Albers D, Birk M, Thimme R, Probst A, Faehndrich M, Frieling T, Goetz M, Riecken B, Caca K. Colonoscopic full-thickness resection using an over-the-scope device: a prospective multicentre study in various indications. Gut. 2018;67:1280-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Duan TY, Tan YY, Wang XH, Lv L, Liu DL. A comparison of submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection and endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric fundus submucosal tumors. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2018;110:160-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li B, Chen T, Qi ZP, Yao LQ, Xu MD, Shi Q, Cai SL, Sun D, Zhou PH, Zhong YS. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic resection for small submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer in the gastric fundus. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:2553-2561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |